In which I ask why Marvel Comics sets its stories in real cities, while DC creates anonymous every-cities. And consider what this does to us as participants in the narrative.

Image Credit: Screenshot from Amazing Spider-Man 2, US Gamer, Amazing Spider-Man 2 Review

I’ve somehow managed to get my 2 year old son obsessed with Spider-Man. It wasn’t hard. I’ve always loved Spider-Man’s off-the-wall (or on-the-wall) antics, and there’s something about the playful red/blue/web aesthetic that I just enjoy. I also love that clichéd line “with great power comes great responsibility”… I was never all that into Spider-Man myself. I was an avid reader of The Phantom as a kid.

Xavi and I have been watching The Ultimate Spider-Man together. A pretty fun cartoon. Mostly it’s fun for me. He has a Spider-Man figurine that he takes to bed. And so, I thought it’d be fun for me to grab a copy of The Amazing Spider-Man 2 on the PS4. And it has been fun. Though mostly for me.

In the last few years I’ve enjoyed the resurgence of comic book worlds in TV and Cinema. I love the Marvel Universe (except for the relatively insipid Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D). I thought Nolan’s Batman trilogy was great, and Arrow and The Flash are TV favourites in our household. Robyn isn’t so sure about Gotham. But I like its gritty gangster vibe, and its introductions of villains from Batman’s world have drawn me back into the Batman mythos a bit.

As I was swinging from building to building as New York’s friendly, neighbourhood, Spider-Man, it got me wondering — why is it that Marvel’s universe co-opts real world cities as a back-drop for its stories, while DC has invented the likes of Gotham, Metropolis, Central City and Starling City? What is gained through this decision? What is lost?

I’ve been thinking a bit about questions of place and story lately. And I’ll get to a bit of theological unpacking of these questions in some subsequent posts.

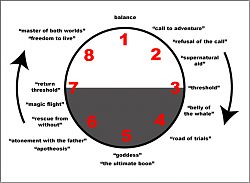

I while back I posted a bunch of lectures from TV show-runner extraordinaire Dan Harmon (of Community fame) about how stories work (and some stuff from Ira Glass and Kurt Vonnegut). The shape of stories Harmon talks about in those lectures is pretty much the shape of every comic book story ever created (and every story ever told), and he said this, which I think is true:

“Sooner or later, we need to be someone, because if we are not inside a character, then we are not inside the story.” — Dan Harmon

Video games obviously make this process easier by giving you a character to play. Eyes to see through. An avatar. They bring us into the story via a character — other stories through other mediums have to do this in other ways, and as a result of web-slinging my way around New York, I’m wondering what role place plays in getting us inside a character. Do we get into a story, and into a character, quicker if the setting is one we know, or one that exists in our world, or does an ‘every-city’ do the job faster?

I’m also wondering what role comic books — or fantasy in general — plays in giving us a picture of a re-enchanted world. A world where good and evil are locked in a battle, not just in a natural sense, but supernaturally. I’m wondering how they might teach us something about compelling story-telling that helps us help people see the world truly.

All this. Just as a result of playing a video game about a comic book character…

Our Disenchanted world

I’ve been reading quite a bit of James K.A Smith lately. One of the ideas at the heart of much of his writing is that our modernist, ‘secular,’ world is a disenchanted world. A flat world that has lost a sense of meaning beyond the physical reality. He suggests that in moving to an epistemology (method of knowing stuff), ontology (understanding of what stuff ‘being’ ‘stuff’ is), and a philosophy (materialism, the way we bring these two together), that emphasises the material world above all else we’ve collapsed any transcendent (stuff beyond us, and our senses, and ‘ultimate’ stuff) reality into an immanent (stuff around us, that we experience and observe) reality. That is: we don’t ask questions about supernatural stuff. About magic. About God or gods — because all that really matters is what we (collectively, and individually) see, hear, feel, and experience.

The effect of this has been to disenchant the world — which has an impact on our art and culture as much as it does on the way we think about knowing, and the sciences. Our art becomes less enchanting. Our stories, even our ‘myths’ — not untrue stories, but the stories we live by — become more worried about the immanent.

But. Maybe the world isn’t as disenchanted as it appears to be. And maybe superhero stories are an invitation for us to consider our desire to be enchanted. One of Smith’s books I’ve been reading is How (Not) To Be Secular its a short commentary on Charles Taylor’s A Secular Age. in it, Smith says:

Taylor names and identifies what some of our best novelists, poets, and artists attest to: that our age is haunted. On the one hand, we live under a brass heaven, ensconced in immanence. We live in the twilight of both gods and idols. But their ghosts have refused to depart, and every once in a while we might be surprised to find ourselves tempted by belief, by intimations of transcendence. Even what Taylor calls the “immanent frame” is haunted.

One of the ways out of a disenchanted world, via these haunted remains, is through the arts — and — specifically, through stories. Comic books are a type of art (even if high art types might criticise them as being ‘pop’ culture). They’re also a type of story particularly given to doing this work because they’re visual stories, not just words on a page. They’re also, often, an ‘epic’ sort of story capable of functioning as myth, and with a hero designed for us to care about, and identify with (but more on heroes in the next episode). Both the Marvel and DC universes, via their comic books, but also their multimedia platforms represent a billion dollar sector churning out stories people want to immerse themselves in as they read, watch, and play.

“The cinema has never before seen anything quite like the “Marvel cinematic universe”. This sometimes tightly, sometimes loosely connected skein of films and television shows draw on characters the comic-book publisher (now also a movie company owned by Disney) has been developing for decades. Begun in 2008 with “Iron Man”, its exercise in extended mythopoeia now consists of 11 feature films and three television shows, with many more to come… The studio has successfully explored a range of trappings and stylings for its superheroes, putting them in character pieces and ensembles, setting their stories in outer space and in congressional hearings, playing them for thrills, or laughs, or both. There has, though, been something of an amped-up sameiness to the recent offerings, with third acts dominated by variations on the theme of a large-flying-object-laying-waste-to-a-city-with-possible-world-changing-conseqences.” — Ant Man: The Smaller Picture, Economist

These stories matter. The settings matter — these cities that are laid waste matter. The ‘laying waste’ matters within those worlds, it has potential consequences that we largely ignore as viewers, but the authors are no longer interested in letting us ignore, nor are they interested in ignoring them as storytellers who are world building — that’s what that word ‘mythopoeia’ means in the quote above.

These stories are also a window into the way people experience the haunting of our ‘immanent’ world at a ‘pop’ level. They are art. Pop art. I don’t think ‘pop’ should carry any sense of snobbery, because what this really means is that its a popular way that people in western society get their little taste of enchantment. Even if the way these comic universes are set up (as we’ll see) are often products of an immanent view of the world.

Just briefly, as a bit of an answer for anyone who has bothered to read this far who is still thinking “what’s the point” of all this — the point is this. Too often our methodologies as Christians, the way we speak the Gospel and live it — buys into this immanent frame, and produces a sort of immanent Christianity that never touches the transcendent, or gets close to this haunting sense people have. One of our goals, as Christians who believe in a supernatural — something beyond our senses — and an archetypal hero — must surely be to give people a new vocabulary, and a new way of seeing the world. Our task in speaking into the secular world — the stories we tell — are stories, or ‘myths’ that are ‘enchanted’ and true.

Now. Back to the question at hand. What difference does it make to the story if its set in the “real” world, or in a created world? Are we most likely to see the world as enchanted if the ‘myths’ or stories we live by that give us models for action, and help us think through meaning are set in the real world, in real cities, or in fictional every-cities? What is more relatable?

It turns out this is a debate that goes as far back as CS Lewis and Tolkien, who both wrote about the importance of ‘faery stories’ and creating worlds shot through with meaning. Worlds where the transcendent was not collapsed into the immanent. Worlds where magic still happened. Enchanted worlds. Worlds that could speak to those haunted parts of our minds and help us see meaning in our own world. So we’ll unpack that a bit too. My basic thesis is that Tolkien advocates a DC approach to story telling, while Lewis would adopt Marvel’s approach. So, for example, the humans in Narnia are citizens of earth who arrive in the enchanted world of Narnia through a wardrobe, while the humans of Middle Earth are natives of this alternative, still overtly enchanted, world.

Although, Lewis understood that enchanted stories needed to take place a little beyond our little immanent bubbles of reality. Beyond our own place — our own city.

“It is not difficult to see why those who wish to visit strange regions in search of such beauty, awe, or terror as the actual world does not supply have increasingly been driven to other planets or stars. It is the result of increasing geographical knowledge. The less known the real world is, the more plausibly your marvels can be located near at hand.” — CS Lewis, On Science Fiction

The effect of dislocation into these enchanted places was meant, for Lewis, to help people carry that experience into their everyday reality. To re-enchant the world.

“He does not despise real woods because he has read of enchanted woods; the reading makes all real woods a little enchanted.” — CS Lewis, On Three Ways of Writing for Children

But are comic books really the equivalent of the Lewis/Tolkien approach to faery stories? Can we really think these forms of pop culture can do what the literary work of two of the 20th century’s most prodigious literary geniuses were able to do? Is there any comparison between DC’s Gotham and Tolkien’s Middle Earth? Or Marvel’s New York and Lewis’ London? Or even perhaps Marvel’s Asgard and Lewis’ Narnia?

In the next couple of posts I’ll unpack what Tolkien and Lewis teach us about building worlds embedded with meaning, and I’ll consider the role of heroes within these world building stories. Who knows when those posts will be finished. For now lets continue on this question of what sort of place, or setting, provides the quickest path to re-enchantment. A real city, enchanted, or an ‘enchanted’ city we’re invited to see as a city we belong to…

Comics and the “real” world

Comics, as stories, are an interesting lens through which to unpack the values of the world that produces them, and they also play a part in shaping the world we live in. Comic book characters are no longer reduced to two dimensional avatars that move through panel by panel, they’re now brought to life in TV shows, Movies, and video games. We can, as I’ve experienced this week, see the world — our world — through their eyes, and so seeing, can be invited to re-see our world differently through our own eyes.

It’s interesting that in their current iterations the significant difference between DC and Marvel is that, thanks to the aesthetic of Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight, DC products tend to be darker, and grittier than Marvel’s, and ultimately, despite Superman coming from another planet, I think they’re somewhat less overtly enchanted or magical than Marvel. Marvel’s cinematic universe — with the exception of the new Netflix Daredevil series (and we’ll discuss it in a subsequent post) operates in a world soaked in vivid colour. Neither comic universe really engages in the magical realm quite so much as Lewis or Tolkien. Whether its New York or Gotham or Metropolis, these stories still occur in something close to the real world. And yet the ‘enchantment’ of the superhero still needs to be explained, this is truer in Marvel’s universe — Batman (DC) and Ironman (Marvel) both operate as functions of their wealth, and the opportunity created by such wealth, Superman (DC) and Thor (Marvel) are both ‘out of this world’ heroes from above, bringing a sense of enchantment to earth, while the rest of Marvel’s heroes are essentially ‘enchanted’ when the immanent world backfires, or, when science misfires. The ‘enchantments’ are largely not enchantments at all, but products of immanence (the question of whether God/gods exists in these universes is an interesting one that I’ll unpack a bit later too). As my friend Craig Hamilton put it when I asked him (and others) the question that drove this investigation:

“The DC universe is about the ideal whereas Marvel is about struggling to live up to an ideal. DC heroes are almost pure archetypes while Marvel are heroes with feet of clay. Even Batman isn’t a brooding vigilante he’s The World’s Greatest Detective. Marvel has a fearful, suspicious stance towards technology and science that DC doesn’t have. Most of Marvel’s heroes and villains are the result of science gone wrong. The Fantastic Four, Spider-man, Hulk. It’s fear of radiation that creates all these heroes. And they’re fundamentally flawed characters in a way that DC heroes aren’t. Sure Superman has kryptonite and Green Lantern’s ring didn’t work on yellow for a while, but that’s totally different to Tony Stark being an alcoholic weapons manufacturer or Peter Parker being responsible for his Uncle’s murder and being driven by that guilt forever while continuing to make stupid decisions and needing to fix his mistakes.” — Craig Hamilton

The X-Men, a Marvel franchise, are another example of enchantment via immanence — super powers developed via mutation, rather than enchantment being a natural product of a world that includes an accepted, and largely unquestioned, transcendent reality (ala Gandalf and Aslan).

Regardless of the origin of the powers of the hero, these stories have always had a mythic quality, the ability, via a sort of enchantment, to function as myth and cause us to understand our ‘immanent’ reality differently.They’ve always had this sort of power. Regardless of their setting — but a really interesting example of the differences between Marvel’s real world stories and DC’s stories that come from fictional cities set within the real world, came in World War II.

While being perennially dismissed as juvenile, comic books functioned as powerful propaganda in World War II, which took place just as superheroes were emerging as icons. DC Comics Superman and Batman, who existed in their own fictional ‘every-cities’ took part in the war effort by modelling an ideal citizenship — a citizenship of responsible consumption — cracking down on petty crime and irresponsible use of resources back home, while Marvel’s characters, especially Captain America, coming as they did from real cities, were able to participate in the war effort.

The question of setting is already playing a part in the way comic book stories function as ‘myth’ stories that shape us. Stories that use a sense of enchantment to reshape the lives of the people and cultures who both read them and produce them. What’s interesting in the question of setting, is that regardless of universe, all the action is really taking place in one city. Vancouver.

Or, rather, New York. “Every City” or not, comic book drama takes place in that great city.

That great city: Gotham, Metropolis and New York

“Originally I was going to call Gotham City “Civic City.” Then I tried “Capital City,” then “Coast City.” Then I flipped through the New York City phone book and spotted the name “Gotham Jewelers” and said, “That’s it,” Gotham City. We didn’t call it New York because we wanted anybody in any city to identify with it. Of course, Gotham is another name for New York.” — Batman Writer/Co-creator, Bill Finger

“The difference between Gotham and Metropolis succinctly summarizes the differences between the two superheroes. As current Batman editor Dennis O’Neil put it: ‘Gotham is Manhattan below Fourteenth Street at 3 a.m., November 28 in a cold year. Metropolis is Manhattan between Fourteenth and One Hundred and Tenth Streets on the brightest, sunniest July day of the year'” — Dennis O’Neil, Batman Writer, cited in ‘Metropolis is New York by Day, Gotham City is New York by Night,’ BarryPopkik.com

The locus of superhero comics was then, as it largely remains, New York. Writers and artists living in the city depict it in their work — so successfully that superhero stories set in any other city may require a certain degree of justification for their choice of locale.” — Richard Reynolds, ‘Masked Heroes,’ The Superhero Reader

But why New York? Making an ‘every-city’ based on New York is interesting, because it’s already an every-city.

“The anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss described his reactions on arriving in the city in the essay ‘New York in 1941’: “…New York (and this is the source of its charm and its peculiar fascination) was then a city where anything seemed possible. Like the urban fabric, the social and cultural fabric was riddled with holes. All you had to do was pick one and slip through if, like Alice, you wanted to get to the other side of the looking glass and find worlds so enchanting that they seemed unreal.” This is the New York (or Gotham City, or Metropolis) that dominates the superhero story and has become its almost inevitable milieu. New York draws together an impressive wealth of signs, all of which the comic-reader is adept at deciphering. It is a city that signifies all cities, and, more specifically, all modern cities, since the city itself is one of the signs of modernity… New York is a sign in fictional discourse for the imminence of such possibilities — simultaneously a forest of urban signs and an endlessly wiped slate on which unlimited designs can be inscribed — cop shows, thrillers, comedies, “ethnic” movies… and cyclical adventures of costumed heroes as diverse as Bob Kane’s Batman and Alan Moore’s Watchmen.” — Richard Reynolds, ‘Masked Heroes,’ The Superhero Reader

What’s interesting is that these comic universes — even these comic New Yorks — have to grapple with questions of the relationship between people and place. Both people in these worlds — and the impact they have on the places they occupy, and the impact these places have on the people who occupy them, and the people and events outside the world and the impacts these people have on the fictional, enchanted universe of these stories. A question that flows from this is what do these ‘enchanted’ places do to people in the real world — via the power of story.

What places do to people, what people do to places

“Batman is integrally linked to his city, the city he has sworn to protect. In every sense of the word, he is a true avatar of Gotham. And Gotham City itself is an avatar, not only of the dreams of its fictional architects, but of our collective urban paranoia.” — Jimmy Stamp, ‘Batman, Gotham City, and an Overzealous Architecture Historian With a Working Knowledge of Explosives,’ Life Without Buildings

There’s a sense amongst the literature on Batman, especially the Dark Knight Batman, that Gotham’s dysfunctionality is, at least in part, due to the sort of person, or sort of hero, he is. His ‘myth’ — his power as a symbol — is built on fear. He wears a mask. He strikes fear into the hearts of those who do wrong in the city, and yet, this perpetuates a kind of criminal in Gotham who needs to be fearless (or insane) to operate. It’s a vicious cycle. Batman is shaped by his city, and thereafter he shapes his city.

In the real world, as readers or viewers visiting Gotham, the city has the capacity to both embody our fears about criminals unchecked by conscience, and the ‘worst’ of city life. If the writers of Batman have quite deliberately based their ‘enchanted’ city on New York’s worst districts, at night, then this fictional place starts to reinforce certain fears in us, as we read. The Dark Knight is a certain sort of post-modern hero who turns the table on the way this ‘enchantment’ works from being light and magical to being dark, if not a dark art, or sorcery, at the very least a sort of defence against the dark arts that comes from us seeing humanity reflected at its worst through the magic mirror, rather than at its best in the, albeit masked, visage of the superhero.

“Since its inception, Gotham City has been presented as the embodiment of the urban fears that helped give rise to the American suburbs, the safe havens from the city that they are. Gotham City has always been a dark place, full of steam and rats and crime. A city of graveyards and gargoyles; alleys and asylums. Gotham is a nightmare, a distorted metropolis that corrupts the souls of good men.”— Jimmy Stamp, ‘Batman, Gotham City, and an Overzealous Architecture Historian With a Working Knowledge of Explosives,’ Life Without Buildings

Architecture, real or enchanted, shapes the people who ‘live’ in it. It makes us feel. It’s a form of art, and thus, able to enchant. Or haunt. As my web-slinging avatar flew through the streets of New York, and as the impressively animated city was corrupted, burned, and blown up by bad guys, and an hyper-vigilant anti-hero agency, I felt things about the destruction of the city. I don’t know if this felt ‘realer’ because it was New York, a city I’ve never visited, but the setting was part of the story. It helped it touch some haunted part of me, or put me in touch with something enchanting. It got me asking the sort of questions that led me to read a bunch of stuff and write these posts.

“Architecture influences the lives of human beings. City dwellers react to the architectural forms and spaces which they encounter: specific consequences may be looked for in their thoughts, feelings and actions. Their response to Architecture is usually subconscious. Designers themselves are usually unconscious of the effects which their creations will produce.” — Hugh Ferris, An Architect/deliniator from New York from his book, The Metropolis of Tomorrow

Comic book architecture also reacts and responds to the real world. It has to, to keep us engaged. This becomes part of the motivation (apart from a desire to do-over a stupid plot line) for a comic book trope called retconning. The “retcon” is a portmanteau of retroactive continuity. It’s a sort of on the fly editing of a back story to account for a change in the present. From what I’ve read in the last couple of days, Frank Miller’s introduction of the Dark Knight version of Batman was an incredibly powerful and effective retcon, with a fitting story. It was a retcon that took place because of a cultural shift. It enabled Batman to be interestingly post-modern, asking new questions in storylines and for us as readers (but more on this in a future episode). Apparently Superman started off as something of a Robin Hood, who robbed from the rich and was a little anti-establishment, but as soon as World War II kicked off he became the face of the ideal American. These retcons seem necessary. But some are dumb. Other retcons, or changes, are forced because of physical changes in the real world — like the 9-11 destruction of the Twin Towers. There are other changes that are less retconny and more trendy.

“Miller’s revisionary realism is only another version of what comic books often accomplish in the narrative, a literal revising of the facts of a comic book character’s history on the basis of recent interpretation. Take, for example, the design of Superman’s home planet, Krypton. The rendering of a “futuristic” world looks very different today than the rendering done in 1938. Today, however, Krypton is portrayed anew and is expected to be understood by readers as the true rendition of how Krypton has always looked. — Geoff Klock, The Revisionary Superhero Narrative

But places are also, increasingly, affected by the events that take place inside the comic book universe. This is interesting because it makes the stories set therein simultaneously ‘realer’ in that there is an effect following a cause, and less real, in that the ‘real’ version of the city is increasingly removed from the story version. A story-teller particularly committed to their craft would have to start literally blowing up cityscapes to keep a continuity between the real world and the story world. Over time, the change inflicted on the physical landscape in the story could make the events more distant from us, if they didn’t become opportunities to present us with new questions. It’s funny that in one sense, Marvel’s New York is moving closer to DC’s, especially Dark Knight DC’s, Gotham.

One of the profoundly cool things about Netflix’s version of Daredevil is that it happens in the same Marvel universe as the films. And this becomes part of the story. The events shape the people. There’s continuity — which according to Reynold’s in a book called Superheroes: An Analysis of Popular Culture’s Modern Myths — is a thing that Marvel’s Stan Lee introduced into the world of comics as a key innovation in what he identifies as the Silver Age of Comics (these ‘ages’ are contested a bit). So it’s true to Marvel’s DNA. This continuity is interesting because Daredevil, via Netflix, has a sort of gritty aesthetic more at home in Gotham. Daredevil’s New York is gritty. And its grittiness is a result — a direct result — of the wanton destruction of New York in The Avengers. Daredevil confronts the fallout of the destruction of this city so prominently featured as the landscape for Marvel’s epic cinematic universe. This universe, a universe grappling with the destruction wrought upon it by these conflicts, and changing as our real world changes too, becomes the backdrop for increasingly complex stories, stories where we’re haunted by both our very immanent reality, and the real, physical, consequences of decisions made in the real world, but where we’re also haunted by a lingering sense of the transcendent, and the idea that even now, though we might deny it, our world is shot through with meaning. The Marvel Universe is becoming even more ‘fallen’ in a Biblical sense, as the impact of human, and super-human, failings are felt at an environmental level. Marvel’s universe, like DC’s, and like our own, is frustrated and groaning as a result of sin. But this makes the world meaningful, and real.

CS Lewis wrote a book called The Discarded Image in which he explores how our modern approach to knowledge displaced the idea that there is meaning beyond the material. He writes about the medieval model of the world, a world imbued with all sorts of meaning. A world which functions as a backdrop for stories — art — that is more enchanting than the art we produce as a result. We start handicapped, like a runner 20 metres behind the start line, because we’ve lost our sense that the everyday forest is enchanted already. Our fictional forests are as bland as the run of the mill forest of the medieval model. Our comic book villains are less magical, and our heroes are the product of science experiments gone wrong. They’re not the sorts about whom bards might sing.

In every period the Model of the Universe which is accepted by the great thinkers helps to provide what we may call a backcloth for the arts. But this backcloth is highly selective. It takes over from the total Model only what is intelligible to a layman and only what makes some appeal to imagination and emotion. Thus our own backcloth contains plenty of Freud and little of Einstein. The medieval backcloth contains the order and influences of the planets, but not much about epicycles and eccentrics. Nor does the backcloth always respond very quickly to great changes in the scientific and philosophical level. Furthermore, and apart from actual omissions in the backcloth version of the Model, there will usually be a difference of another kind. We may call it a difference of status. The great masters do not take any Model quite so seriously as the rest of us. They know that it is, after all, only a model, possibly replaceable. — CS Lewis, The Discarded Image

Romans 1 suggests we suppress the transcendent reality of our world, and exchange the transcendent supernatural God, in whom we exist, for a bunch of immanent gods — worshipping created things. Romans 1 shows that the world, as it was intended to be, is an enchanted space where we should be coming face to face with the divine, and its only our deliberate blinkers, our wilful intent to not see, to not be enchanted, that leaves our world more two dimensional than a comic strip universe (a world where meaning and enchantment still exist).

The wrath of God is being revealed from heaven against all the godlessness and wickedness of people, who suppress the truth by their wickedness, since what may be known about God is plain to them, because God has made it plain to them. For since the creation of the world God’s invisible qualities—his eternal power and divine nature—have been clearly seen, being understood from what has been made, so that people are without excuse.

For although they knew God, they neither glorified him as God nor gave thanks to him, but their thinking became futile and their foolish hearts were darkened. Although they claimed to be wise, they became fools and exchanged the glory of the immortal God for images made to look like a mortal human being and birds and animals and reptiles. — Romans 1:18-23

Enchanting stories: Stories that bridge the gap between the immanent and transcendent

The contemplation of the actual Metropolis as a whole cannot but lead us at last to the realization of a human population unconsciously reacting to forms which came into existence without conscious design. A hope, however, may begin to define itself in our minds. May there not yet arise, perhaps in another generation, architects who, appreciating the influence unconsciously received, will learn consciously to direct it?” — Hugh Ferris, from The Metropolis of Tomorrow

Breaking this ‘suppression’ and the blindness that comes with it requires the world to become enchanted again, in some sense this requires the enchanted worlds that teach us that our world, too, is enchanted, to become more compellingly enchanted. That’ll help. It also involves us shifting our model for understanding the real world, to include the transcendant. This is another one of those vicious cycles. Our models are influenced by art and story, just as they influence art and story. Paul’s answer to the world broken by our fascination with the immanent in Romans 1 is a story, the story about how the transcendent one broke through. How God took the first step. How he provided a hero. Here’s a spoiler. The answer at the end of this series, wherever it leads, is going to be Jesus, because Jesus, in the incarnation, is the perfect character (a character almost every superhero, but especially Superman, rips off in some way). This isn’t your typical Jesus juke. I think it’s true in a profound and enchanting way.

But the answer is also us telling better, more enchanting, stories. Learning something from DC and Marvel, sure, but looking back to times when the world was more enchanted, or to those who engaged, deliberately, in the construction of enchanted worlds. Whose approach to ‘architecture’ or to world-building was an intentional attempt to direct us not just to something enchanting, but something truer than true about our own world. Stories require people (heroes) doing things in places, over time. So the next two episodes will explore that. But now. Some James K.A Smith on why we need stories.

“So what does this have to do with stories? Well, our hearts traffic in stories. Not only are we lovers, we are also story-tellers (and story-listeners). As the novelist David Foster Wallace once put it, “We need narrative like we need space-time; it’s a built-in thing”. We are narrative animals whose very orientation to the world is most fundamentally shaped by stories. Indeed, it tends to be stories that capture our imagination—stories that seep into our heart and aim our love. We’re less convinced by arguments than moved by stories… The philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre says that stories are so fundamental to our identity that we don’t know what to do without one. As he puts it, I can’t answer the question, “What ought I to do?” unless I have already answered aprior question, “Of which story am I a part?” It is a story that provides the moral map of our universe…

Stories, then, are not just nice little entertainments to jazz up the material; stories are not just some supplementary way of making content “interesting.” No, we learn through stories because we know by stories. Indeed, we know things in stories that we couldn’t know any other way: there is an irreducibility of narrative knowledge that eludes translation and paraphrase…

So it is crucial that the task of Christian schooling is nested in a story—in the narrative arc of the biblical drama of God’s faithfulness to creation and to his people. It is crucial that the story of God in Christ redeeming the world be the very air we breathe, the scaffolding around us… we constantly need to look for ways to tell that story, and to teach in stories, because story is the first language of love. If hearts are going to be aimed toward God’s kingdom, they’ll be won over by good storytellers.” — James K.A Smith, Learning (by) Stories

So. What difference does it make if the story is set in real New York or New York in a mask? Perhaps not much. What matters is how enchanting the story is, or how much the use of the city is able to haunt us by pointing us to some truth beyond ourselves. To get us to remove the mask, or the blinkers, we wear that stop us truly seeing the world around us as enchanted, and shot through with meaning. A place where we might meet real heroes, and even behold the divine.