“We faithful orthodox Christians didn’t ask for internal exile from a country we thought was our own, but that’s where we find ourselves. We are a minority now, so let’s be a creative one, offering warm, living, light-filled alternatives to a world growing cold, dead, and dark. We will increasingly be without influence, but let’s be guided by monastic wisdom and welcome this humbly as an opportunity sent by God for our purification and sanctification. Losing political power might just be the thing that saves the church’s soul. Ceasing to believe that the fate of the American Empire is in our hands frees us to put them to work for the Kingdom of God in our own little shires.” — The Benedict Option, pg 99

The Benedict Option? Or is it?

The Benedict Option by Rod Dreher has been making waves long before the book was published so much that many have seen the book as a refreshing opportunity to get some clarity from Dreher about exactly what it is he means when he speaks of the Option; is he talking about withdrawing from the world? retreating to a bunker? being the church in the world? or simply a strategy for disciple making in the modern west?

He’s been accused of calling Christians to head for the hills; and accused those who say so of misrepresenting him.

He’s been accused of responding to the changing world with fear; and accused those who say so of misrepresenting him.

He’s been accused of suggesting Christians abandon worldly institutions (like the political realm); and accused those who say so of misrepresenting him.

I’ve read lots from Dreher (both pre- and post- release of the book), and lots of people talking about The Benedict Option. I think the difficulty as I’ve read the reviews and his responses is that I think Dreher has been misunderstood, but I think he’s also misunderstood the responses (and fuelled them), and that the problem is that Dreher is attempting to present a series of practices — an orthopraxy — for any Christians to reinforce and preserve our faith in a hostile world (he goes so far as to suggest Muslims should do this too), but he fails to account for how different belief systems — orthodoxies — view the world and God’s work in it. Because Dreher writes so broadly, for Protestants, Catholics, and his own Orthodox tradition, and assumes you can work from a right orthopraxy upwards to an orthodoxy, he’s been ill-equipped to handle responses that read from an orthodoxy downwards. The real problem is that his orthopraxy is actually a product of his orthodoxy, and it never really escapes that, but there are many, many, principles and practices he recommends that can and should be adopted by people whose orthodoxy is in the reformed, evangelical, tradition.

“People are like, ‘This Benedict Option thing, it’s just being Christian, right? And I’m like, ‘Yes!’… But people won’t do it unless you call it something different. It’s just the church being what the church is supposed to be, but if you give it a name, that makes people care” — The Benedict Option, pg 142

Another problem is that there are several times where he wants to have his cake and eat it too; he says, for example, that he’s not advocating withdrawal, but then he says Christian parents must pull their kids out of public schools and into either home schools or Christian liberal arts institutions, that Christian workers should abandon ‘contested’ professions (or be pushed out) and be entrepreneurial, starting great businesses but only hiring Christians (and that we should also buy Christian); even to the point of uprooting from life in hostile environments. There’s a protectionism at the heart of his approach to the church and the world.

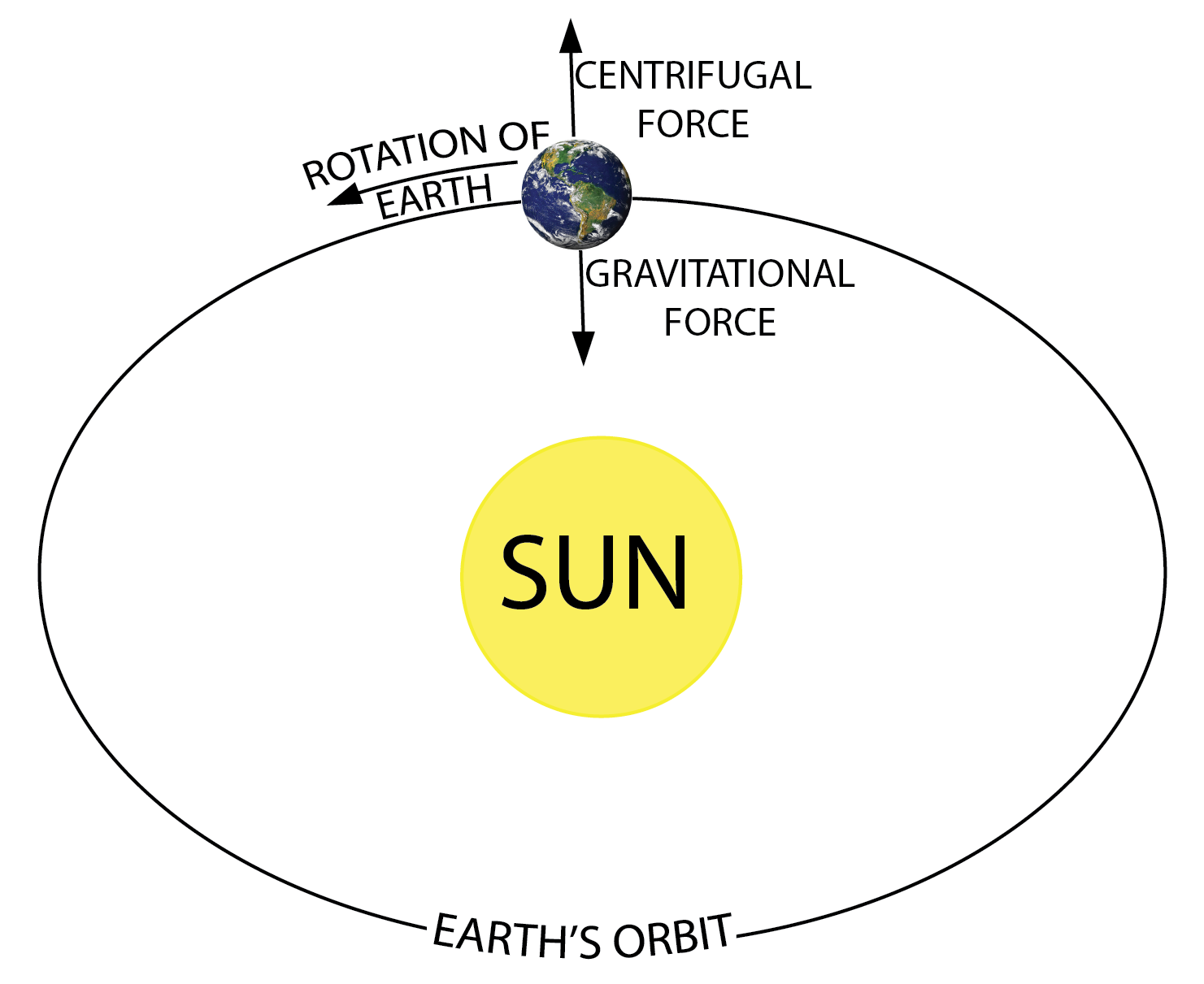

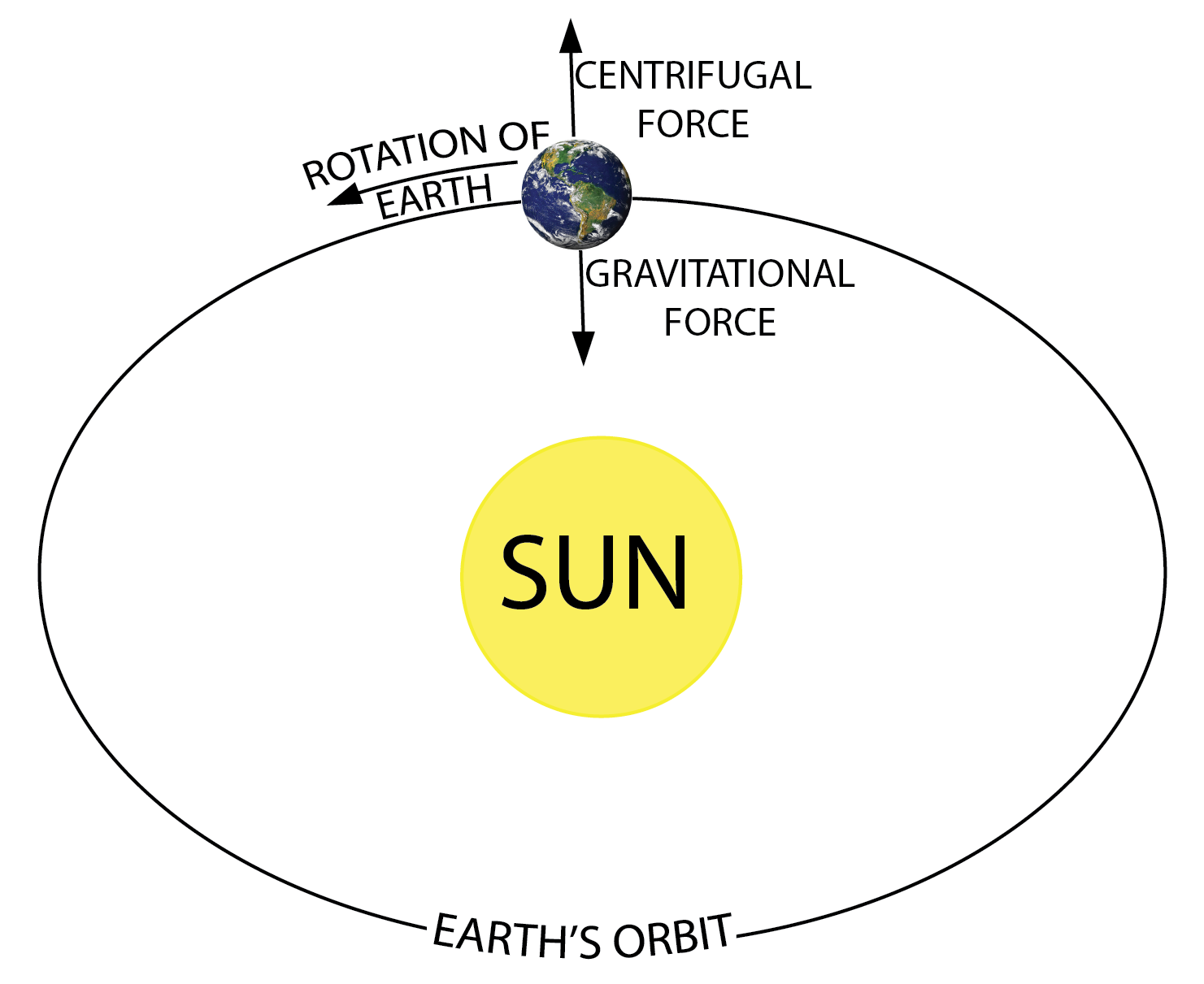

The Benedict Option sees centripetal force — creating more pull in the church than in the rest of space — as our strategy in a post-Christian world; and life as a competition between the gravitational pull of two bodies — the ‘world’ and the Gospel. To be super confusing, in this diagram ‘the world’ (the earth) is us, the ‘world’ is the cosmos. Gravitational force is ‘centripetal’ so replace the ‘sun’ here with the ‘son’ (for the ultimate Jesus-juke)… but also the church, the Gospel, and God.

The problem is that the centrifugal force created by our motion, that keeps us orbiting around the sun, is also an important part of the picture (both in the diagram and in the church). Dreher’s approach to being Christian in the world and engaging with the world is centripetal (pulling people in) rather than centrifugal (sending people out); and there’s probably a case to be made that the church should be both at the same time; that we should be creating a sense of loving, Gospel-shaped, community that is so beautiful as to have its own gravitational pull, but that this community should shape us so that we can respond to and participate in the world outside the church without fear of being flung off or caught up by the gravitational pull of some other body.

Dreher tries very hard to be optimistic and bold but he does so in the face of a tsunami-like narrative regarding a current cataclysm for the church that is, in part, of his own making and imagination. I don’t mean that it isn’t true; I mean that he is the prophetic voice proclaiming it as true. It’s his account of history and the present that his solutions are confronting (though he marshals plenty of supporting voices). He wants to simultaneously build an ark so that the church can survive and one day thrive, and play the weatherman proclaiming that the flood is coming. It’s not new to have to balance a message of salvation and judgment, but if one thinks the flood is different (has been here for much longer, namely, since the crucifixion of Jesus), or that the design for the ark is faulty, Dreher’s rhetoric can feel panicked and urgent. A little bit Chicken Little; not because the sky isn’t falling, so much as that it fell some time ago… and it’s actually that it’s really starting to bite us now. It’s also not that Dreher’s solutions lack creativity — his chapters on work, on education, on politics as local institution building, and on community (both local and church) are fantastic and contain plenty of fodder for churches to chew through. I’m also a bit confused about how he offers his historical account of where things went wrong largely focused on ideas (until he gets to the industrial revolution), and then his solution is largely focused on practices.

I share, to some extent, Dreher’s analysis of what he calls liquid modernity and the pressures the modern world places on Christians, I share the sense that part of the solution is a radically different community-based approach to life in this world. I’ve written about the Benedict Option already a couple of times — once thinking about Christianity as an X-Men like mutation, the other considering aggressive secularism as something like a zombie apocalypse; and I’ve considered what sort of recalibration of church life might be required in a “post-truth” world (and earlier started penning some ‘theses’ around an ongoing ‘reformation’ of the church). I share Dreher’s communitarian vision, and the sense that these must be communities built on rhythms and practices (liturgies) even, that counter the ‘liturgies’ of the false worship around us. I’ve read enough Stanley Hauerwas, James Davison Hunter, Alisdair MacIntyre, and James K.A Smith (and enough Augustine, and the Epistle to Diognetus) to be on board with the central thrust of Dreher’s solution; we need to invest our time and energy into creating communities geared towards the formation of Christians who will face a world hostile to Christianity. This is probably urgent. It has probably been urgent for some time.

“Here’s how to get started with the anti-political politics of the Benedict Option. Secede culturally from the mainstream. Turn off the television. Put the smartphones away. Read books. Play games. Make music. Feast with your neighbours. It is not enough to avoid what is bad; you must also embrace what is good. Start a church, or a group within your church. Open a classical Christian school, or join and strengthen one that exists. Plant a garden, and participate in a local farmer’s market. Teach kids how to play music, and start a band. Join the volunteer fire department” — The Benedict Option, pg 98

You can see why people are confused. In the same paragraph Dreher calls us to secede and to participate in public life. And this is the tension that drives the book (and arguably the tension underpinning our life as Christians who are ‘in the world, but not of it’). The answer to this tension, and where I think at times Dreher doesn’t quite hold the tension, is that we Christians might not be ‘of’ the world; but we certainly should be for it. There’s a couple of things in this quote, and the book, that bother me in terms of his theologies of art and technology (he values ‘high’ art over pop culture, and ‘local’ low-tech forms of media over ‘high-tech’ globalised forms, which is slightly more elitist than, for example, Luther’s approach to pop culture artefacts — precisely given their formative power at a popular level; that power can definitely be used in a ‘deforming way’ — especially when uncritically adopted by the church into its practices (see James K.A Smith), but might also be part of a ‘centrifugal’ push into the world).

I don’t share Dreher’s sense that the tipping point is the sexual revolution (and increasing activism about LGBTI rights); I think we’ve needed this solution for some time. We’ve already had our imaginations and desires conscripted by capitalism and an anthropology that sees humans as economic units who should be educated so that we can get a good job, develop new technology to control the world, and buy the stuff we want. We needed recalibrating long before corporations were signing up as LGBTI allies. I share the concerns of many that when Dreher writes, his perspectives (even as he travels abroad) can’t escape his whiteness, or his Americanness; now, the tagline of the book is “A strategy for Christians in a Post-Christian Nation”, so I don’t want to assess him for not having a broad enough scope; but there are plenty of marginalised communities operating within America as churches already, and instead of talking to them, Dreher headed off to a monastic community in Europe, and talked about the Mormons. The point at which the rubber really hits the road for me in terms of disagreement with Dreher, and how his orthopraxy clashes with my orthodoxy is on the question of education, and the best way to form our children to be Christians in the world. I know there are those within a reformed framework that share Dreher’s thoughts about the dangers of public education; but I don’t want to shape my kids to live in the world by having them box at shadows from the safety of a ‘home school’ or exclusively Christian school context (Dreher is down on church schools where many of your kids peers will be non-Christians who’ll pull them away from Jesus); I want my kids to learn to be in the world as Christians by being in the contested space of the world, with me (and their village) alongside them, not thrown into the world as adults for their first real ‘fight’ with people whose experience and understanding of the world is utterly foreign to them. I do share Dreher’s love for liberal arts educations though; and think Christians should be proactively starting alternative educational institutions for all built on this model because it is better for everyone.

80% of the Benedict Option contains really good and vital ideas and practices that should be factored in to how we approach life as the church in the world. I think what’s missing, or different, from a Reformed Evangelical perspective, is a vision for how to be in the world confident that it is God who saves and sanctifies and he does this through the Spirit, by faith. As someone in a different camp to Dreher, I think he puts too much faith in works to shape us, and is too afraid that the world will claim us; if you stand in the Calvinist tradition we certainly have a role to play in raising our kids in the Gospel-shaped community of the church, teaching them the Gospel in both word and practice, but we do this confident that it is ultimately God who acts to save, not our investment in our children. This should allow us to confidently engage the world with the belief that we have a more beautiful and compelling story that will be effective for those whom God calls, by the Spirit, through our presence.

“We have talked so far in this book about what it means to create the structures and take on the practices that train our hearts to be the Lord’s good servants first, even to the point of sacrifice. This is what the Benedict Option is supposed to do: help us to order all parts of our lives around him” — The Benedict Option, p 194

One of the issues with Dreher’s work, and the ensuing conversation, is that he really has considered and articulated a response to most objections; it’s just unclear which statements to weigh more heavily; ultimately your take on this book will be one of choosing which paradoxical bits to emphasise, or if you can live in tension; so he says:

“Communities that are wrapped too tight, for fear of impurity will suffocate their members and strangle the joy out of life together. Ideology is the enemy of joyful community life, and the most destructive ideology is the belief that creating utopia is possible” — The Benedict Option, pg 139

Yet so much of The Benedict Option reads to me like Moana’s father and his vision for community life on a dying island. So much of its strategy seems to be ‘stay on the island, the island is safe, good, and beautiful, and people have all they need here,’ and yet so much of the solution to liquid modernity seems actually to be found in the Gospel continuing to go out into the world, to challenge the powers and authorities of this world. This paragraph features everything that is right and wrong about The Benedict Option:

“We should stop trying to meet the world on its own terms and focus on building up fidelity in distinct community. Instead of being seeker-friendly, we should be finder-friendly, offering those who come to us a new and different way of life. It must be a way of life shaped by the biblical story and practices that keep us firmly focused on the truths of that story in a world that wants to obscure them and make us forget.” — The Benedict Option, pg 121

This vision is contradictory to an evangelical orthodoxy — a belief that the Gospel is the central story of the world and the church community — and that the Gospel is the story of the son of man coming to seek and save the lost (Luke 19:10), and that we, as the ‘found,’ via the Spirit, become seekers in turn (John 20:21, Matthew 28:18-20). Dreher has emphasised the need for a centripetal community that has its own centre of gravity, at the expense of the centrifugal force created by the Gospel at the centre of our community. The Christian life is the life governed by this tension; by these twin poles simultaneously holding us close to God, and throwing us into the world as his people. It’s also possible that it is in part being thrown into the world that shapes our love for God and the Gospel. The challenge of course, facing the church, is that the world has its own centripetal pull on our hearts — that’s how idolatry works — and part of the work of formation (and how the Spirit appears to work to form us) is making sure how hearts keep being pulled by Jesus with more force than the world can exert. The solution the Benedict Option offers in part, to the pull of the world, is to avoid that pull altogether. It seems, in part, that mission beyond the boundaries of the community in Dreher’s world is a specialised role (and perhaps this is a result of his orthodoxy shaping his orthopraxy), not a role of the ‘priesthood of all believers’ or the body of Christ corporately in the world (except in creating the centripetal force of Christian community).

Just as there’s much to be said for Dreher’s emphasis on practices that cultivate a love for, and trust in, God, I think there’s a good positive case to be made for many of Dreher’s options — like starting counter-cultural liberal-arts schools built on the assumption that a person is more than their economic contribution, or creating ‘thick’ local communities built on charity, or becoming ‘social entrepreneurs’ whose goal is to make something good for people rather than operate for profit — as positive ‘neighbour love;’ good things that we can invest in both as Gospel witness and as expressions of common grace for our neighbours. Where I feel the solutions of his ‘options’, based on the Rule of St Benedict, fail is in their centripetal impulses, their protectionist streak, and their failure to genuinely grapple with the scope of Jesus’ command to love our neighbour, and the universal imperative at the heart of Jesus’ so-called ‘golden rule’. The institutions built via a true Christian option that follows the so-called golden rule, and the command to love our neighbour, will be equally good and available to everyone; public institutions for the common good; not simply private institutions for Christians.

“So in everything, do to others what you would have them do to you, for this sums up the Law and the Prophets.” — Matthew 7:12

One problem with The Benedict Option is that it ultimately fights fire with fire; the world is increasingly going to force Christians out, says Dreher, it will create institutions that do not make space for Christian belief to flourish — including public schools — it will be harder for Christians to maintain jobs in both the public and private sector… and his solution is to create our own exclusionary spaces; not totally exclusive, certainly, we’re still to provide hospitality in our monasteries to those who are curious, but we should keep our kids from the influence of non-Christian peers.

The irony seems lost on Dreher; that as the hostile institutions of our culture (public and private) take steps to keep people from the influence of Christians we would do the same in our own ‘mirror’ institutions and communities. The golden rule is not ‘treat others as they treat you’ but ‘as you would have them treat you’… note that Jesus says here that this ‘sums up the Law and the Prophets,’ so it shouldn’t surprise us when he returns to this theme a bit later in Matthew’s Gospel when Jesus is asked what the greatest commandments are for his people; the ones that should organise life in his kingdom. My sense is that Dreher emphasises the first, without thinking about how the second flows both out of, and into the first.

““Teacher, which is the greatest commandment in the Law?”

Jesus replied: “‘Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind.’ This is the first and greatest commandment. And the second is like it: ‘Love your neighbour as yourself.’ All the Law and the Prophets hang on these two commandments.” — Matthew 22:36-40

Now, it’s fair to say that Dreher’s work gives us plenty of equipment for obeying the first commandment, cultivating a whole-hearted love for God (as opposed to for the world — another big theme in Matthew) and this is a pressing priority in a world where belief in the God of the Bible is contested (to use Charles Taylor’s terminology for our ‘secular age’), and where this contest is increasingly hostile (not just lost in our hearts being captured by alternative visions)… but the ‘as’ in ‘as yourself’ is important; it contains an echo of the ‘golden rule’ — if our solution is not the solution we’d like to see our neighbours practice to us, it’s not the answer for how we engage with them. He also attempts to address these two ‘love commands’:

“Though fear in the face of these turbulent times is understandable… the Benedict Option ultimately has to be a matter of love. The moment the Benedict Option becomes about anything other than communion with Christ, and dwelling with our neighbours in love, it ceases to be Benedictine… it can’t be a strategy for self-improvement or saving the world.” — The Benedict Option, pg 237

The problem is perhaps best expressed in the question Jesus poses in the parable of the Good Samaritan. Who is my neighbour? My fellow Christian? Certainly. But also the people on my street, in my city, and ultimately in the world beyond my national boundaries and the west. He explicitly cites these two commands here, It’s just the failure to mediate them through the golden rule that breaks part of his project; if our neighbours really did have the words of life in their secular agenda, would we not want them to do all they could to bring it to us? How would we have them love us? If we have the words of eternal life, how should we then love? This is where a centripetal model of being the church doesn’t cut it; and where we’re to be centrifugal; to go out; just as Jesus ‘went out’ to us.

One of the best things about The Benedict Option, and the Rules of St Benedict is that they are corporate in their orientation. One of my bugbears with the recapturing of liturgy and practice as tools for formation is that they almost always seem self-interested; like a sanctified masturbation (to borrow from Fight Club’s line about self-improvement); Christian love is love that overflows out of the self and is directed towards God and other. You might argue that a sort of personal love is vital for other love, but I think the practices we see promoted in the New Testament church are largely oriented towards the body of Christ, not just the self. The Benedict Option nails this; I think; in its rich communitarian vision, and this is perhaps a positive product of Dreher’s Orthodox orthodoxy (where protestants/evangelicals tend to be a little more individual in our outlook). But one of the problems with the Benedict Option is that it is not other-focused enough, because in many cases, neighbouring stops at the boundaries of the community (while including visitors to the community). It’s far more concerned about how the world might shape us than certain about how we might, through God’s sovereignty and the Spirit, shape others (and shape ourselves as we seek this).

It’s of course, also interesting, when it comes to the life of the church in a hostile world, that the way Jesus ultimately obeys both these commands is in the hands of the hostile empire, and with his own hands spiked to a bloodied timber execution device… arguably this is what we should expect as Christians operating in the world.

At one point Dreher urges us to ‘rediscover the past’ (page 102) and he heads to Norcia where the modern Benedictines have re-founded a community based on the Rule of St Benedict at the fall of Rome; I suspect he should have looked further back than 1,500 years ago, to what it was that helped a crucified king overturn the very empire that had crucified him; ostensibly as a sign of its power, to crush his claims to the throne. Here’s what the Epistle To Diognetus puts forward as a summary of the Christian strategy in a pre-Christian world; the first half of this quote emphasises the difference in Christian community and practice (and the tension of being in, but not of, the world), while the second half suggests this practice is ‘other-oriented’:

But, inhabiting Greek as well as barbarian cities, according as the lot of each of them has determined, and following the customs of the natives in respect to clothing, food, and the rest of their ordinary conduct, they display to us their wonderful and confessedly striking method of life. They dwell in their own countries, but simply as sojourners. As citizens, they share in all things with others, and yet endure all things as if foreigners. Every foreign land is to them as their native country, and every land of their birth as a land of strangers. They marry, as do all [others]; they beget children; but they do not destroy their offspring. They have a common table, but not a common bed. They are in the flesh, but they do not live after the flesh. They pass their days on earth, but they are citizens of heaven. They obey the prescribed laws, and at the same time surpass the laws by their lives. They love all men, and are persecuted by all. They are unknown and condemned; they are put to death, and restored to life. They are poor, yet make many rich; they are in lack of all things, and yet abound in all; they are dishonoured, and yet in their very dishonour are glorified. They are evil spoken of, and yet are justified; they are reviled, and bless; they are insulted, and repay the insult with honour; they do good, yet are punished as evil-doers. When punished, they rejoice as if quickened into life; they are assailed by the Jews as foreigners, and are persecuted by the Greeks; yet those who hate them are unable to assign any reason for their hatred.

Dreher rightly emphasises that our practices should draw people to us, but what the book lacks is a confidence that these same practices should also unleash us confidently upon the world, from the safety of such a community. He suggests beauty will be part of our witness, but it’s the ‘beauty’ within the metaphorical monastery, and our alternative communities; rather than the sort of faithful presence that James Davison Hunter champions.

“In an era in which logical reason is doubted and even dismissed, and the heart’s desire is glorified by popular culture, the most effective way to evangelise is by helping people experience beauty and goodness. From that starting point we help them grasp the truth that all goodness and beauty emanate from the eternal God, who loves us and wants to be in relationship with us. For Christians, this might mean witnessing to others through music, theater, or some other form of art. Mostly, though, it will mean showing love to others through building and sustaining genuine friendships and through the example of service to the poor, the weak, and the hungry.” — The Benedict Option, p 119

There’s lots to love about this quote; you’ve just got to hold it in tension with his call to move to rural areas apart from hostile civilisation that will counter-form us if we stay… I’m all for Christianity being a creative force from the margins; but I think out ‘marginalisation’ is felt more when it’s buttressed against the ‘centre’ than when it is removed from sight from those we are seeking to reach (or when we are removed from the reach of the ‘centre’ ourselves).

Dreher is also worth heeding inasmuch as he recognises that our job as the church now is not to win the culture war; but we need more, it’s not enough to simply become a ‘counter-community’ that centripetally draws people in. God is a sending God; we’re sent into the world as Jesus was sent into the world, commissioned to ‘go to the ends of the earth’ with the promise that God is with us… this isn’t a calling to go out and set up centripetal communities — new Israels — but to be a beautiful, alternative community, that goes into the world confidently modelling the beauty of our community and our trust in God even as it crucifies us. To be the sort of faithful witnesses envisaged in Revelation, a set of instructions for life as exiles in a hostile world; in Babylon… in Rome.

“Now when they have finished their testimony, the beast that comes up from the Abyss will attack them, and overpower and kill them. Their bodies will lie in the public square of the great city—which is figuratively called Sodom and Egypt—where also their Lord was crucified. 9 For three and a half days some from every people, tribe, language and nation will gaze on their bodies and refuse them burial. The inhabitants of the earth will gloat over them and will celebrate by sending each other gifts, because these two prophets had tormented those who live on the earth.

But after the three and a half days the breath of life from God entered them,and they stood on their feet, and terror struck those who saw them. Then they heard a loud voice from heaven saying to them, “Come up here.” And they went up to heaven in a cloud, while their enemies looked on. — Revelation 11:7-12

Perhaps rather than a plurality of ‘Benedictine communities’ across different orthodoxies (including Dreher’s suggestion that muslims and jews might adopt the same strategy) a better solution in the ‘secular age’ of ‘liquid modernity’ that is hostile to non-consensus views is to model how we wish to be treated; perhaps a confident pluralism is more in line with the golden rule and our hope; not confident that we will win our place in the world, but that the ‘categorical imperative’ of doing unto others as we would have them do (and as Jesus categorically did as a ‘categorical indicative’) is actually the right thing to do, and the right way for us to be formed, because we are confident that Jesus is victorious. Here’s how writer John Inazu (who wrote a short response to The Benedict Option) describes his strategy for life in the post-Christian world; in his book Confident Pluralism: Surviving and Thriving through Deep Difference:

“The goal of confident pluralism is not to settle which views are right and which views are wrong. Rather, it proposes that the future of our democratic experiment requires finding a way to be steadfast in our personal convictions, while also making room for the cacophony that may ensue when others disagree with us. Confident pluralism allows us to function—and even to flourish—despite the divisions arising out of our deeply held beliefs… Confident pluralism explores how we might live together in our deep and sometimes painful differences. We should not underestimate the significance of those differences. We lack agreement about the purpose of our country, the nature of the common good, and the meaning of human flourishing.”

The way to operate well in this world, following the golden rule, while also cultivating the sort of thick communities that help us love God and offer others the sort of love that we have had him offer us, as his co-missioned church, might not be to shut ourselves off from those who disagree with us, but rather to make space for them to speak, confident that when we also speak, our story is better, our community richer, and our practices more compelling to those whom God calls. Confident that the prayer of Jesus will be answered in us as we are sent into the world by Jesus to love like Jesus.

“My prayer is not that you take them out of the world but that you protect them from the evil one. They are not of the world, even as I am not of it. Sanctify them by the truth; your word is truth. As you sent me into the world, I have sent them into the world. For them I sanctify myself, that they too may be truly sanctified.” — Jesus, John 17:15-19