This is an amended (and extended) version of a sermon I preached at City South Presbyterian Church in 2022. If you’d prefer to listen to this (spotify link), or watch it on a video, you can do that. It runs for 37 minutes. I’m going to be honest, 90% of the reason I started posting these sermons is that I think the title of this post is pretty great.

What’s your utopia?

Your picture-perfect society — not your heaven on earth place, or ‘thin place’ from the last piece, but your idea of a heaven-on-earth people or community?

500 years ago the English philosopher Thomas More imagined an ideal society in Utopia. In his vision kings were generous not corrupt; there was no private property, just abundance, and everyone ate meals together all the time…

Some of you are thinking that sounds like hell.

It wasn’t ‘eu-topia’ — “the good place” — but ‘u-topia’ — “no place” — more knew this was impossible.

Anna Neima wrote this fun book, The Utopians, deep diving into six post-World War One, post-Spanish flu communities that tried to build ‘the good place’ as a response to the combined trauma that emerged out of a pandemic and a war.

She describes utopias as:

“A kind of social dreaming. To invent a ‘perfect’ world – in a novel, a manifesto or a living community – is to lay bare what is wrong with the real one.”

There’s a prophetic function to these attempts to re-order relationships. The catch, she concludes — none of them worked, they promised too much change from the status quo, but couldn’t deliver. She wrote:

“These experiments in living all ended up facing a similar set of problems… There were tensions between the ideals of cooperation, egalitarianism and democracy, and the practice of elitism and hierarchy.”

This can end up being true not just of our view of the perfect society – whether that’s family, or church, or a sharehouse. Our utopian visions often end up no places not good places because they all involve people and end up as a product of the hearts of the people living in them.

We zero in on the first good place today, and the first ‘ideal human society’ where two humans face a choice; a life-or-death choice between eutopia and dystopia; between two trees: the tree of life and the tree of knowledge of good and evil. There’re plenty of other trees to eat form too, but these two trees represent a choice between loving and listening to God — trusting him as good source of goodness and fruitful life, or rejecting god and pursuing wisdom and life in some other way. To eat from the Tree of Life is life, to eat from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil is death.

I’m going to go out on a limb here — to suggest humans aren’t pictured as immortal creatures, but dust animated by god’s breath depending on the Tree of Life to live forever. A little later in Genesis, God will say his breath won’t contend with human flesh forever (Genesis 6:3). So when humans are cut off from the Tree that means being cut off from forever life, and facing death as de-creation; becoming dust again.

At the end of Genesis 2, the man, or “earthling,” and woman made from his side are together, united, and things look good. They are destined for oneness; created to represent God, fruitfully multiplying and ruling the world together; based in the garden in Eden, to work it and guard it together; not alone. We’re also told they’re naked and unashamed (Genesis 2:35). This lack of clothing is an interesting point for the author to make; it’s almost unimaginable for us to feel this safe while naked. Imagine feeling safe to turn up to church naked without judgment or fear; was that part of your utopian vision? The reasons we don’t do this are pretty obvious, right? And when we probe these reasons it doesn’t take long to find sin and brokenness in the mix — ours and other’s. The point here is that things are good and safe and glorious. And oneness is a real possibility; oneness in purpose — in rule – in generative life that brings fruit. The oneness doesn’t last long though.

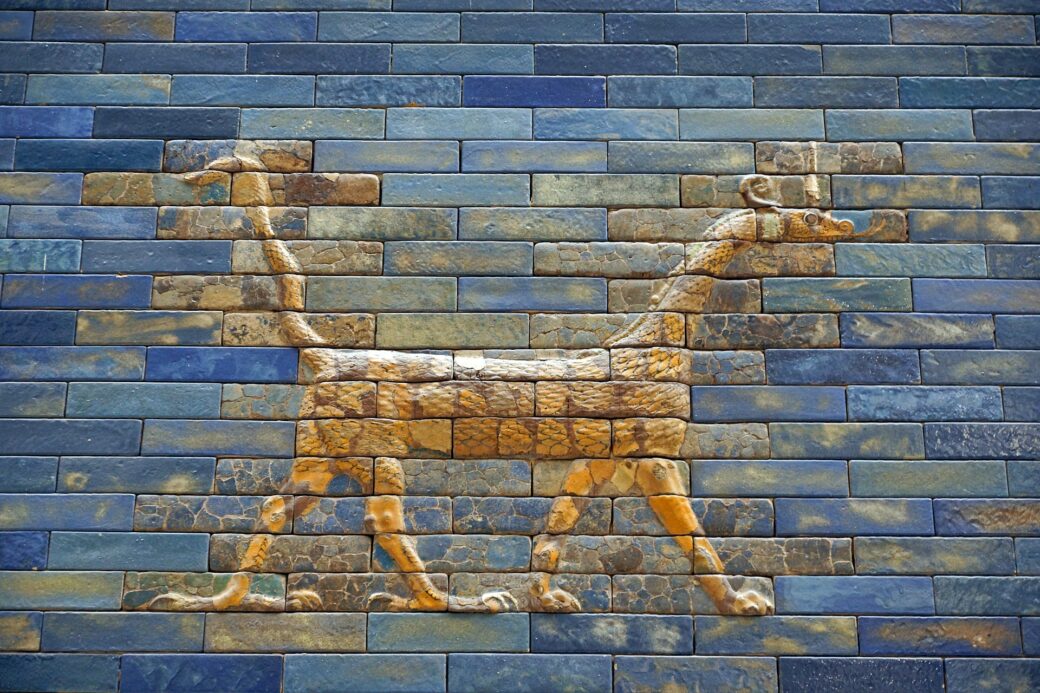

We meet this chaos figure, this serpent (Genesis 3:1). Imagine it with legs, too. Like a dragon. Like this sort of ‘divine’ beings you might find pictured with kings in Babylon or on their architecture.

Image Source: Wikipedia article The Mušḫuššu, Image from Wikipedia Commons.

The serpent’s crafty. It’s a wild animal — a “beast of the field” in Hebrew; the sort of creature humans were meant to rule over (Genesis 1:28), it’s also leading a rebellion on earth that we’ll see echoed in heaven. It’s a threat to the good and fruitful order of the world.

I suspect guarding the garden (Genesis 2:15) probably meant keeping sinister critters out; especially critters the humans are meant to be ruling over. Maybe these humans should’ve crushed the intruder’s head straight up, especially as the serpent speaks with a forked tongue, “did God really say “you mustn’t eat from any tree in the garden” (Genesis 3:1). God says nothing of the sort. Right up front the serpent is reframing God as a miser — as someone who restricts rather than graciously giving — this isn’t the God we’ve met so far in the story who makes and shares fruitful and beautiful life and wants to see it spread and enjoyed. God said they could eat freely of every tree — including the tree of life. There’s just one choice that leads to death.

And the woman does her bit to set him straight, only, she adds some stuff to god’s instructions. She creates a restriction — a boundary — that wasn’t there before. The seed of doubt has been planted.

We can do that too. Create rules that sound righteous, but actually restrict good things God has given us. The trick is actually listening to God’s word; and contemplating his good creation. God did not say they couldn’t touch the fruit on the tree in the middle of the garden.

And so the serpent twists. You can eat. You should eat. God’s holding back. God doesn’t want you to be like him. You won’t die. Your eyes will be opened and you’ll be like god knowing good from evil.

Now, pause, because this bit is important. In our work through Genesis one and two we’ve seen that God made humans with the exact purpose that they be like him. It’s hard to imagine that being like him means being ignorant about what good and evil is. There’s an issue with how we picture knowing as being about the head alone, about information, not about experience, or right relationship — as we worked through the Wisdom literature together we saw that wisdom is actually about right action — action aligned with truth (note: this is a reference to an earlier sermon series I might repurpose as articles one day too, but that you can find on our podcast here).

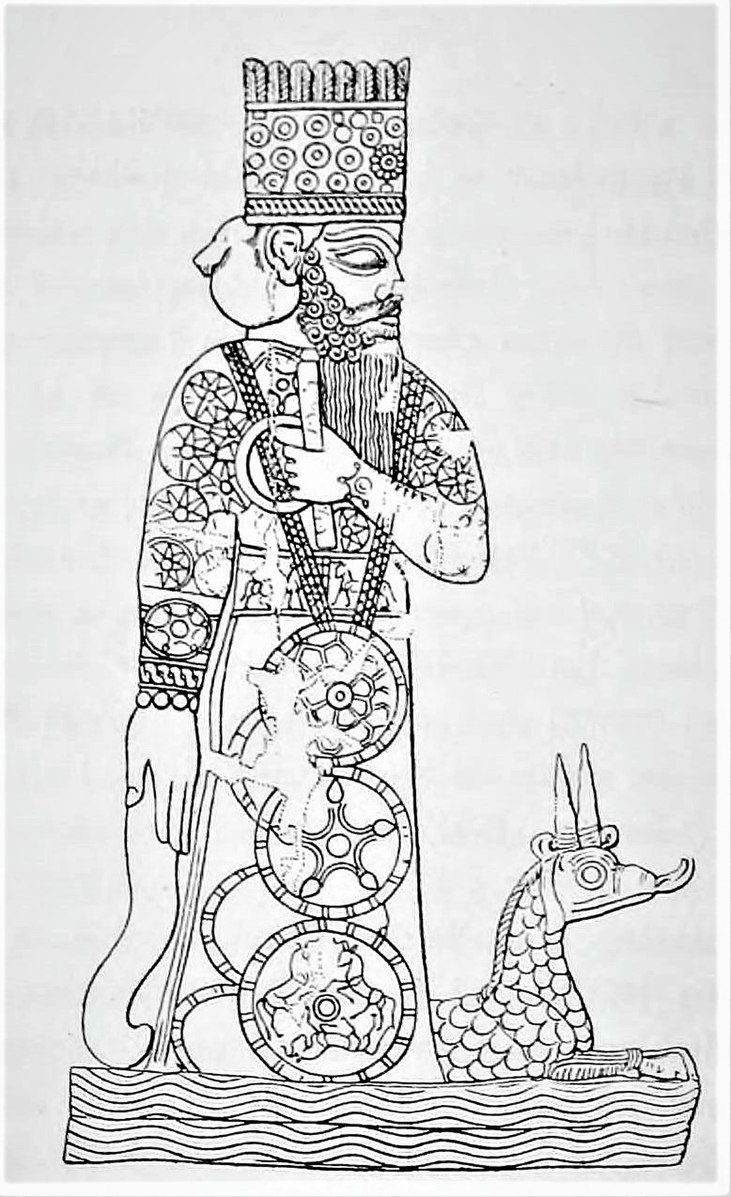

What the serpent is actually offering is an opportunity for them to make themselves like gods who get to decide good and evil for themselves; apart from God their creator. To speak rather than listen, to be laws unto themselves, to grasp hold of autonomy and be their own images of god, like the kings of the nations around Israel. It’s interesting that these kings — and their gods, like Marduk, get pictured with little dragon gods – serpents — next to them.

Image Source: Wikicommons, 9th century BC depiction of a Statue of Marduk.

I think it’s a legitimate question to ponder why God made this tree; what it’s doing in the Garden — what its purpose is and in what sense it does what it is named after. I suspect the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil was a test, but also a teaching aid; providing wisdom to humans who contemplate it as a beautiful gift from God, along with his instruction, rather than grasping hold of it in disobedience to God. It operates just like wisdom in the Old Testament operates; where the fear of the Lord is the beginning of knowledge and wisdom (Proverbs 1:7).

The question in this interaction with the slippery serpent is will the humans fear and listen to God?

I wonder too if the idea was always that humans were meant to ask God for wisdom; God seems to delight in giving wisdom to his people — like with King Solomon, who’s pictured as a new Adam, naming the animals and plants (1 Kings 4:32), and who asks for exactly this sort of wisdom — not just to know right and wrong — but good and evil — it’s the same words in Hebrew — in a way that pleases God (1 Kings 3:9). Solomon asks for a listening heart because he needs this sort of heart and wisdom to rule as God’s representative.

So long as these humans were in the garden, listening to God, obeying him, enjoying him, and contemplating the tree, they actually were knowing good and evil, and finding life, and being like God, the way the rest of the Old Testament frames it.

Humans should be ruling over the wild animals — the beasts — but the serpent tips the world upside down. They should be co-operating in the task of guarding the garden and representing God as his priestly people — the sort who speak his word into the world. They were meant to be being like God, but they take matters into their own hands

There’s no joint pondering of God’s word and testing it against the serpent’s, just impulsive action in the belief that God is holding something good back and we’re better off deciding good and evil for ourselves. There’s joint action — the woman sees — she sees the fruit is beautiful and pleasing to the eye (Genesis 3:6), which is how the fruit in the garden has been described (Genesis 2:9). And I think we’re meant to believe it is beautiful even that it looked delicious. She’s attracted to it, and I wonder if contemplating its beauty, but not taking something that is forbidden might have been, and might still be, a path to wisdom. But then she declares the fruit that God has said is “not good to eat” is “good to eat” — and she eats it, and she gives some to her husband — the flesh of her flesh — and he doesn’t say “stop,” he eats too (Genesis 3:6). There’s not just one sin here — not just one action — the whole thing, from the moment they let the serpent misrepresent God uncorrected, to the moment they add to what God has said and so present God as miserly and harsh, to the moment the woman takes the fruit — it’s all a failure — a joint failure to be like God.

They eat the fruit and everything changes; suddenly their nakedness is a massive problem (Genesis 3:7). They make clothes out of leaves — dressing themselves like trees; they become what they’ve worshipped. They identify themselves with the bottom of the food chain — the very things given to them to eat (Genesis 1:29, 2:9), but from here on they aren’t going to be as fruitful as they could’ve been. There’s now a barrier between them; and worse — a barrier between them and God; and a loss of this function reflecting his glorious image.

God turns up to walk in the Garden. This word used here is a way his presence is described with Israel through their history — both in the tabernacle, and temple. This walking — it’s part of the Eden-as-temple package. God comes to be present with his people, and they hide from him (Genesis 3:8-9). They’re dressed as trees trying to hide in the trees — the original camouflage — as though God won’t find them. They are ashamed. But God calls for them.

And Adam calls back. “I heard you. I was afraid. I hid” (Genesis 3:10-11).

That’s not how we were meant to respond to God. This isn’t the relationship they were created for as representatives of God’s rule. And God — like a parent catching their kid with a face covered in the chocolate they weren’t meant to eat — asks if they’ve been eating what they shouldn’t. He knows what’s going on… “who told you that you were naked? Have you eaten from the tree that I commanded you not to eat from?” (Genesis 3:11). I wonder if things could’ve gone differently at this point too, but the man straight up fails to own the one flesh nature of what’s just gone down; the barrier between man and woman becomes obvious. He blames the woman, and he blames god for putting her with him; ‘I can’t be fruitful because of her and you,’ “she gave me the fruit and I ate it.” And she blames the serpent. Nobody takes responsibility. Nobody repents. They shamelessly blame others (Genesis 3:12).

God recognises they’re all complicit, so, as a result, more barriers are put up to fruitfulness. The first two chapters have been about the desolate and uninhabited lands becoming fruitful places inhabited by God’s image bearing people who reflect his rule in the world. This can’t happen without people being like God and listening to him, and pursuing wise life in his presence — trusting his goodness and enjoying his hospitality — his provision of life. And now, this is frustrated. Cursed. The serpent bites the dust. It is cursed “above” all the other livestock by becoming below them; crawling on its belly and eating dust (Genesis 3:14).

The serpent and its offspring are set at odds with humans and their offspring; in keeping with the tree-fruit metaphor the word for offspring here is seed. Serpent-spawn will strike the heel of the seed of the woman, while there’ll be a seed produced from the woman that’ll crush the serpent’s head (Genesis 3:15).

For the woman, fruit-producing, childbearing, is going to be frustrated. This word encompasses everything about that process from sex to birth. It’s a breaking of the relationship with the man; they’re meant to rule together, but now there’s a cursed hierarchy (Genesis 3:16). The patriarchy as we know it (and as it unfolds in the Bible’s story) isn’t god’s good design; it’s part of the curse (this doesn’t mean we should accept it any more than we should refuse to fight against weeds and thorns in the production of food). We saw last week that ‘helper’ meant more than servant – it meant ally — where men rule over women like this we see curse at work.

While for earthling-Adam — suddenly the earth is a rival and a destiny. Instead of cultivating a garden from a garden, with god’s life-giving help — the ground is now cursed because of ground-man. Eating will be a result of painful toil. Thorns and thistles will be an expression of curse (Genesis 3:17-18).

And they’re both going to die; to return to the ground. Dust to dust. Earthling to earth (Genesis 3:19).

Now earthling — Adam — exercises rule over eve, he names her like he named the animals. Something has shifted (Genesis 3:20). She’s still going to be the mother of the living — but they’ve become like beasts not like God; and God dresses them up in animal skins — you are what you wear — they’re not trees, but wild things — ruled by the serpent — rather than ruling (Genesis 3:21). And as God declares this curse on humans in verse 22, the Hebrew we get translated as “has become like us” is ambiguous, it can also be “was like us” (note: Old Testament scholar Doug Green as a whole lecture on this idea that he once gave at QTC that was profound for me, and I think, unlike the Serpent, has legs).

I think we’re meant to ask the question of that ambiguity: were humans like God, and now they’re not, or have they in this moment become “like god” as an act of idolatrous or treasonous self-actualisation. The answer is they were like God, or they were meant to be — and now they’ve tried to make themselves into gods, just like the kings of the nations — but they’re actually beastly.

As a result, they’re exiled from the garden (Genesis 3:23). It’s what happens to Israel when they want to become like the nations by grasping hold of power and idols and rejecting God as creator too; they get kicked out of the fruitful land and sent to Babylon. Israel’s story echoes this origin story. Beastly humans don’t get the Tree of Life; they don’t get immortality and life with God in his garden (Genesis 3:23). They’re outside the garden. East. Outside the gates.

God’s still in the picture, but they aren’t in the garden anymore. And now there’s a heavenly being — a cherubim — wielding a flaming sword (Genesis 3:24). A heavenly being, doing the work Adam and Eve should’ve done; guarding the garden; keeping out the beasts; the wild things, the beings not committed to bringing a heaven on earth society as God’s representatives — which now includes these beastly humans.

They can’t live forever as beastly critters, enjoying the Tree of Life. So what do we do with this story?

It becomes a story for God’s people, Israel, to contemplate; both when they’re headed towards a fruitful land again, and invited to choose life in Deuteronomy (Deuteronomy 30:19-20), and when they’re in the valley of the shadow of death, in Babylonian exile. Where they’re contemplating what went wrong again; how history repeated, as they too tried to be gods on their own terms, rather than being like god; and how this got them there. The pattern of sin we see bring curse into human relationships repeats (internationally or systemically, and individually) through the Old Testament — seeing, desiring, declaring things God has said are not good as good and taking them; pursuing life, deciding good and evil on our own terms, and it keeps leading to exile and death.

And yet — the pursuit of wisdom itself — through listening to god’s word — becomes a tree of life (Proverbs 3:13-18). The person who plants themselves in god’s word becomes like a fruitful tree (Psalm 1:1-3). For the Israelite reading these words in exile in Babylon, surrounded by the people of a beastly king, that path back to Eden; back to life is obvious: listening to God.

The prophets also promise the way back to Eden-life will come through a faithful seed; a branch of a tree, the “root of Jesse,” so a son of David, a tree-son, who’ll delight in the fear of the Lord (Isaiah 11:1-3), this figure will create an Eden like land where animals are at peace and serpents aren’t a threat anymore, and the earth will be filled with the knowledge of God (Isaiah 11:8-9).

A fruitful tree will emerge. A king. An image of God who leads us to life with God, while crushing the serpent. Jesus — the branch of Jesse — comes to lead us back to blessing — to fruitfulness — to a pattern of life that doesn’t look like the curse.

At his arrest, John tells us that Jesus enters a garden; Gethsemane (John 18:1), where he doesn’t grasp and decide what is good and evil, but gives himself to God, saying “not my will but yours” (Matthew 26:39), before people storm the garden, wielding clubs and swords (Matthew 26:47). The Greek word for club here is the word for wood and tree that gets used in the Greek version of the Genesis story for the two trees — they come into a garden wielding trees against the branch of Jesse. They come wielding trees, committing treason against the tree-son (look, that’s pretty good).

Jesus is arrested and taken off to face a beastly trial — treated like an animal — he has a crown of thorns pushed into his head — the picture of the cursed ground pressed into his skin (Matthew 27:35). Then he’s stripped naked and crucified — nailed to a cross — publicly shamed as he’s nailed to a tree. The cross is described using that same wood word (Acts 13:28-29). Jesus absorbs the worst the world and the serpent can throw at him. His death on a tree isn’t just him taking on curse — as Paul puts it, but an exchange of his life for ours in a way that secures forgiveness of our sins, our redemption from curse, and our restoration as people of God as we receive his Spirit (Galatians 3:13-14).

Jesus comes to restore us from exile, to lead us towards life and wisdom by being the life and wisdom; the living word of God; and we now choose life or death in our choice regarding one tree; the cross. The cross is both our Tree of Life a way to eternal life where God gives his life to and for us, and our Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil, where we find true wisdom; a way of life through contemplation. It’s where we choose to be God’s image bearing children, or to side with the serpent.

We’re invited to stop grasping, to stop trying to be gods, to stop being ruled by sin, to no longer be led by our desires to take what we want in disobedient rebellion against God. So much of my sin is me just repeating that pattern. So many of our utopias — our ideas of the good life — our temptations to sin — involve the serpent’s vision casting — the idea that God is withholding something good from us, or we shouldn’t listen to him, and these visions lead us to grasp and destroy, and they lead us away from god, feeling ashamed, and hiding as our humanity is diminished, and replaced with beastliness as we become what we worship.

Jesus, the tree-son — the firstfruits — gives us God’s Spirit to dwell in us, making us one with God, so we’re no longer hiding from him, but hidden in him; protected, seated with him as his children, and invited to produce the fruit of the spirit in our lives as we give up treason and contemplate the tree-son, as he re-creates us as imperishable humans.

There’re lots of ways the New Testament talks about this re-creation that pick up ideas of what Genesis suggests it means to be human — we become transformed into the image of Jesus; we get clothed with Christ; we become a kingdom of priests and ambassadors of the message of reconciliation; a living temple, and the body of Jesus — united in him, by the Spirit and growing towards maturity in Christ.

We’re invited to a new pattern of life together — we’re not a people who rule over one another, Genesis 3:16 is not our pattern for fruitfulness. So much of church history, like Israel’s history, has involved male leaders operating to protect their power and to lord it over others, and then husbands being told to do that at home. That is curse. Not blessing.

We’re god’s children — with a new way of life we find in the example of Jesus — where we don’t grasp, or give others up, but give ourselves for others in love (Ephesians 5:1). This is utopian. Imagine a world where everyone did this; imagine a you where this was the image you were presenting to the world.

God’s design is for us to rule the world together not by dominating or ruling over each other, but by submitting to one another out of reverence for Christ (Ephesians 5:20). This won’t look like grasping patriarchy, or abusing our power to take what we want, or putting our desires first. This isn’t servant leadership; it’s just service in a body of people who mutually serve. That’s the shape of marriage, and church, it’s a dynamic of loving service.

Our task as “rulers” of God’s world, in whatever context, is to rule together; to lead each other to find life in obedience to God; feasting on our new tree, finding life in Jesus, and so following his example, as we head towards a new Eden, and a new Tree of Life together.

This origin story shapes our life, and our community, so the ‘good society’ isn’t no place, but breaking out in the world as Jesus transforms people and our communities into little eutopias. Even as her book reaches the conclusion that utopian visions fail, Anna Neima doesn’t see them as a waste of time.

She says:

“Utopian living is extraordinarily generative. It creates openings in the fabric of society, inspires change, reminds us that it is possible to reach beyond the dominant assumptions of our day and discover radically different ways of being.”

The world needs communities who live differently — generatively — creating new ways of being that challenge the dominant assumptions of our day and model radically different ways of being.

Jesus invites us to do that.