A few people have asked my thoughts about Victoria’s Conversion Therapy bill, including how I could imagine a church operating in Melbourne under the conditions the Bill seems to present to those who are theologically conservative on issues of sexuality and gender expression/identification. Conversion Therapy has already been banned in Queensland, though the Act that was brought through parliament before our recent election is narrower in its scope than the Victorian proposal.

I have concerns about the Victorian legislation (I have bigger concerns about the church), but they’re not exactly the sort of concerns I’ve been reading my blogging brethren in theologically (and politically) conservative circles expressing.

My concerns are slightly more obtuse and to do with how a secular government operating with the default assumptions that religious truths and practices have no substantial legal standing can then turn around and legislate about religious truths and practices.

It seems to me that this is a weird blurring of church and state that elevates belonging to a church community, and participating in its beliefs and practices, to something non-voluntary. I’m happy to grant that the legislation is particularly aimed at protecting vulnerable children whose presence in church institutions is often not voluntary, but part of belonging to a family who attend a church, and can see analogies between the sorts of conversion therapy targeted by this bill, and the behaviours of church institutions that led to the Royal Commission into Institutional Abuse, but I’m concerned that the bill is not limited simply to protecting children from those who would intervene in the development of their sexual or gender identity, but also seems to prevent adults from voluntarily accessing any services that might fall under the Bill’s definition, whether those services are theologically necessary or not. This, to me, is a curious thing for a government to be pursuing.

I’m also not convinced that any intervention in the psycho-sexual development of a child, or young adult is good or necessary; I’ve heard arguments that for a trans-identifying child that to go through puberty and develop biological features that are not in accordance with their preferred identity is traumatic, but technological intervention to guide development seems to me to be its own ‘conversion therapy’ featuring a vulnerable child, and there certainly seem to be a number of post-intervention individuals wishing they’d acted (or been encouraged to act) more slowly, taking less extreme measures. I recognise, obviously, the privileged position I write from here as someone comfortable in my own skin, whose physical, biological, sex lines up with my gender, who is not neuro-divergent, and who is reasonably secure in my sense of self within the communities I’ve belonged to…

This, also, isn’t to say that children shouldn’t have some human agency, just that most of us as adults recognise that our growth and development and ability to act with wisdom, or even to delay gratification, is something that comes not just with experience but with the maturity of our brains and emotions. Sometimes our job as adults is to say ‘not yet’ or ‘wait’ and to help people ground their sense of self in something other than their sexuality, or gender, and to model delaying gratification and bearing up under tension and examine our desires, and our environment, rather than grasping hold of every technological solution (whether chemical or surgical) offered to us with the promise it will ease our discomfort. I suspect there might be a bunch of cultural and environmental changes that might take some of the pressure off young people navigating their development, and some of that might even look like challenging the idea of identity itself, or the hyper-sexualised environment we make our kids grow up in, along side a culture built on the absolute need to know who you are and act authentically, and to do so by exercising one’s agency through immediate consumer choice and performance.

The Victorian Government’s landing page for the Change or Suppression (Conversion) Practices Prohibition Bill 2020 describes the circumstances that gave rise to the Bill as targeting practices that have caused serious damage and trauma. Then boldly states “it aims to ensure that Victorians are able to live their lives authentically with pride, and makes it clear an individual’s sexual orientation and gender identity are not “broken” and do not need to be “fixed.”

The Bill itself says its intent is:

(a) to denounce and give statutory recognition to the serious harm caused by change or suppression practices; and

(b) to affirm that a person’s sexual orientation or gender identity is not broken and in need of fixing; and

(c) to affirm that no sexual orientation or gender identity constitutes a disorder, disease, illness, deficiency or shortcoming; and

(d) to affirm that change or suppression practices are deceptive and harmful both to the person subject to the change or suppression practices and to the community as a whole.

Now. This is an interesting exercise in public theology from a secular state. And certainly, within the assumed truth and neutrality of a materialist account of personhood — where we are living our best lives when we authentically and pridefully live in such a way that our true self is performed and recognised — an “individual’s sexual orientation and gender identity” are not broken, and don’t need to be fixed (so long as we’re talking about those sexual orientations within the LGBTIQA+ umbrella, or heterosexuality, built on desire for sexual activity between consenting adults). I’m also not convinced that sexual orientation/desires never change (both because fluidity does seem to be a thing in some people’s stories, and because neuroplasticity is a thing), just as I’m not convinced that orientation change is a good or necessary goal for a Christian.

It’s interesting, then, that the Bill, having defined a ‘conversion or suppression’ practice goes on to allow therapeutic support for those seeking to transition their gender (presumably from alignment with biological sex to gender identity, rather than back to biological sex from gender identity). It’s also, I think, problematic that the Bill targets such practices even, explicitly, with an individual’s consent.

I have concerns about the anthropology underlying this bill, the idea that to put a religious conviction above a sexual or gender orientation is ‘suppressing’ one’s true self is an interesting conviction for a secular government to adopt, and elevates the ‘psyche’ above both bodily and spiritual realities (in fact it essentially denies Spiritual realities while targeting spiritual practices as though they are only psychological or physical/material practices). This means I have concerns about its “theology” — this is a Bill that enters into the realm of theologising, coming to particular conclusions not just about the nature of people (and whether there’s a spiritual dimension to our humanity or ‘identity), but about the world itself — because if the material world isn’t all there is, then living in a way that denies spiritual realities, suppressing those or refusing to be changed by them, is also harmful. The government has taken a theological position here, even if not in those terms.

This Bill is not, at that point, “secular” (religion neutral) legislation that enables the sort of pluralism a multi-cultural, multi-faith civic society requires, but “materialist” (and arguably, it’s not materialist, but gnostic, because of the weight it puts on immaterial psychological realities like ‘identity’ over material realities like our bodies and their constituent physical elements). The government may well be right; the material world might be all that exists. We might live in a closed universe with no God, and no spiritual ‘norms’ that we should be seeking to conform to in pursuit of human flourishing. But it’s a bold step for a government to take to push this agenda with a certain amount of certainty when a plurality of beliefs about reality are held in the community it seeks to hold together in a ‘public’ or in a ‘civil’ society. It’s the sort of step that religious groups are tempted to take when they hold the reigns of power; to push for a theocracy, rather than a secular democracy, even if it is a bold step motivated by a genuine desire to protect members of the community from injury or harm.

That said, I have greater concerns about this legislation than ‘what the government is doing’ — my concerns are about the church and our capacity to speak well into this debate, and to conduct ourselves with members of this vulnerable community in the sorts of relationships this legislation is seeking to limit, and particularly in our ability to minimise harm and trauma for those on the margins of our communities.

We’ve got no social capital on this issue. It’s easy to draw a line between conversion therapy practices, the suicide rates in the LGBT community, and both the Royal Commission and the church’s stance on Same Sex Marriage. Whether or not that line bears up under different types of scrutiny, and whether one can infer causation from coincidence or correlation, it certainly bears up in the experience of those lobbying for the law changes whose experiences have often been shaped through first hand experience both of life in Christian communities, and of caring for other members of the LGBT community whose lives have been impacted by church communities. Some of the bits of the ‘line’ one can draw between these socio-cultural phenomena include toxic church leadership and damaging ‘authority’ disparities in Christian relationships where vulnerable people are coerced either by individuals or a culture; and yet, in seeking to eradicate the toxic forms of Christianity in the mix here, there’s a risk it will also target healthy forms of Christianity with a robust understanding of human sinfulness and the need for transformation into Christlikeness for all people, as all of us have our sinful and broken desires (including sexual desires) reordered in and through our relationship with Jesus and the work of the Holy Spirit in our lives. As an aside, it’s become trendy in my neck of Christianity to pile on ‘brokenness’ as some sort of woke/liberal/progressive concession to ‘worldly concerns’ — if there’s one way to point out what’s wrong with that trend, it’s to show that ‘brokenness’ is mentioned by the government, while ‘sinfulness’ isn’t…

The Bill is targeting something broader than just ‘therapy’ in a clinical or professional setting — it’s not just after the horrific practices of electroshock or aversion therapies — but any activity aimed at ‘changing’ or ‘suppressing’ a person’s sexual or gender identity (and again, this is why ‘identity’ is a dangerous concept for us to fully buy into to begin with). It is deliberately broad in its scope, so that the behaviours targeted “include, but are not limited to:

(a) providing a psychiatry or psychotherapy consultation, treatment or therapy, or any other similar consultation, treatment or therapy;

(b) carrying out a religious practice, including but not limited to, a prayer based practice, a deliverance practice or an exorcism;

(c) giving a person a referral for the purposes of a change or suppression practice being directed towards the person.

The Bill also requires, for an action to be taken under the proposed law, that the practice caused injury to the person involve; whether there is the possibility for non-injurious practices like prayer or pastoral support is an open question that the Bill does not seem to resolve.

The thing is, so much of our underlying culture in our communities, whether in behaviours encompassed by this very broad definition or not, is already injurious to LGBTIQA+ individuals seeking to reconcile their faith with their experience of the world.

And here’s where making the distinction between ‘Conversion Therapy TM’ and standard conservative Christian teaching, and the experience of being an excluded minority within Christian communities whose ‘identity’ is targeted for eradication is blurrier than we might think; because, in my observation very few churches are practicing or encouraging anything like ‘Conversion Therapy TM,’ but the experience of Same Sex Attracted Christians in our communities — even those who are ‘Side B’ (committed to a traditional Christian sexual ethic, and so mixed orientation marriage or celibacy) — is one that is often described as ‘traumatic,’ and these brothers and sisters who could and should be the voices we elevate in response to bad, overreaching, legislation are so marginalised within our own communities that it’s possible their sympathies are (rightly) directed to those LGBT people who no longer feel safe or loved by the church (and who, indeed, feel the opposite of safe and loved).

To quote Jordan Peterson, before seeking to change the world — or tackle this legislation — maybe we need to tidy our own room up first.

When we respond to legislation like this saying ‘these practices don’t happen’ — with our own dictionary definition of Conversion Therapy in our pockets to back up our assertion — this is typically expressed by people like me, straighties with institutional power, and no experience navigating life in our institutions as somebody on the margins (particularly those margined because of sexuality or gender divergence). A collection of ‘survivors’ from theologically conservative church communities teamed up with Amnesty International to lobby for this legislation.

There’s a petition on Amnesty’s site that spells out what these survivors are asking for, which is where the broadening of the definition of ‘Conversion Therapy’ — beyond our dictionaries, and the archaic behaviours of electric shock, or aversion therapy — is coming from. Here’s what the petition asks for:

We, the undersigned, call on you to protect people from being harmed by LGBTQA+ conversion practices. Successful conversion practices legislation must:

- Strongly affirm that LGBTQA+ people are not ‘broken’ or ‘disordered’

- Ban practices in both formal (medical/psychology/counselling) and informal (including pastoral care and religious) settings, whether paid or unpaid

- Protect adults, children, and people with impaired agency, including prohibition of the removal of children from a jurisdiction for the purpose of conversion practices

- Target the false, misleading, and pseudoscientific fraudulent claims that drive conversion practices

- Focus on practitioners’ intent to facilitate change or suppression of a person’s orientation, gender identity or gender expression on the basis of pseudoscientific claims

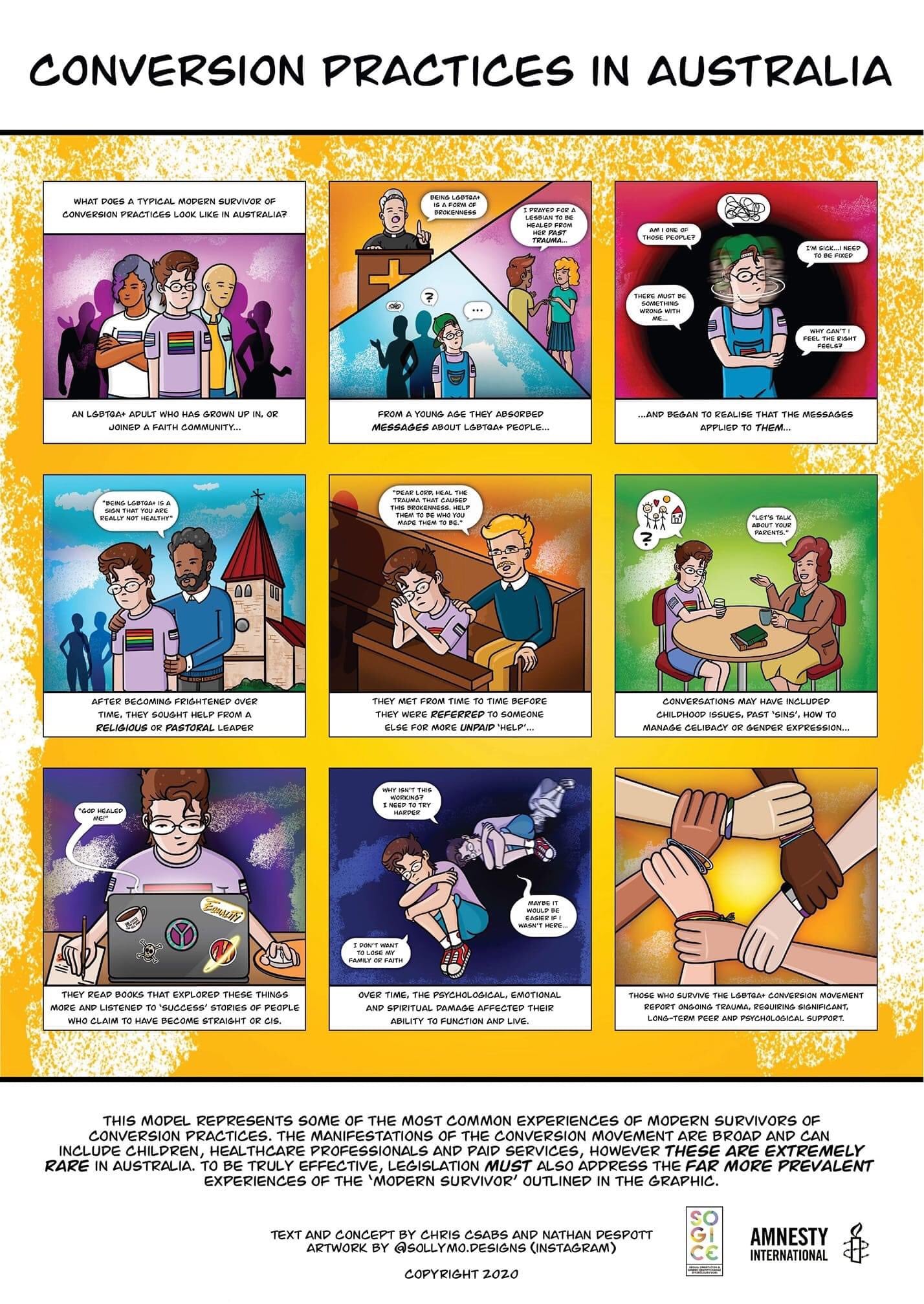

The list is longer than this, but these seem like the key bits of data. Amnesty also produced this comic, that was being shared as separate graphics on Facebook over the weekend.

We can deny ‘conversion therapy’ is happening until the cows come home; but the real experiences not just of those who’ve left our communities, but those who’ve stayed in them but on the margins, are speaking volumes. And there are only a few bits in those graphics that I’d say feel like good and necessary forms of support for LGBTIQA+ people looking to pursue faithful union with Jesus in a theologically conservative setting.

We’re very keen, through our social media platforms (see, for example, Martyn Iles’ post about this graphic) to hold up those same sex attracted Christians whose more fluid orientations or experiences have produced ‘orientation change.’ So, for another example, we’ll champion a popular ex-Lesbian author who writes books and blogs for some major outlets, but we’re not so keen to champion the perspectives of those whose orientations seem stubbornly persistent. We are uncomfortable making space for those who aren’t (and don’t need to) hope for their orientation to be ‘changed’ or ‘suppressed,’ but instead are seeking to ‘re-order’ their loves, and lives, and approach to their bodies, sexuality, and even an understanding of what it means to be a person around the love, or worship, of Jesus (especially if they choose to ‘identify’ as a ‘celibate gay Christian’).

I reckon, if you asked around, plenty of LGBT Christians in conservative Christian communities would resonate with the experiences described in that graphic above; plenty of them are actually supportive of this legislation while maintaining a conservative theological position (including the belief, for example, that it will be the work of the Spirit, in concert with the preaching of the word, not therapeutic intervention, that will convict someone about what faith in Jesus calls them to, and the sort of behaviour that obedience to Jesus requires).

If you ask around you might find that these brothers and sisters feel marginalised and misunderstood by the church, and that when the church and its Cis- male spokespeople so bombastically attack the government for trying to protect hurt and traumatised members of the LGBT community they’re left torn between two sides; the church they love, that keeps hurting them, and their fellow humans whose experiences they can relate to and understand.

This stuff matters.

And it matters when conservative denominations like my own are framing our theological commitments to a traditional sexual ethic, and shaping our public, and pastoral, engagements on issues around sexuality and gender.

My observation is that the more we feel like the outside world is hostile to us on this front, the more our faithful LGBTIQA+ brothers and sisters in our churches, who share our theological commitments, are feeling caught in the crossfire of a culture war. That was recently brought home to me as I spoke to some Side B Christian friends, including my brother in law, an ordained minister in our denomination, after our denomination revisited its public expression of our theological convictions in a way that left them feeling excluded, both from the conversation and the expression of our shared convictions. This process left these friends not only less likely to speak up, but further hurt and marginalised by life within the institutional church, and so, more empathetic with those left in our wake.

And the catch is, the harder the world pushes against our sexual ethic for being harmful to LGBTIQA+ people, the more we actually need the experience for those brothers and sisters in the church to be one of safety, and love — of being understood and supported in their transformation, not towards heterosexuality, or even gender-conformity to our particular norms, but towards godliness (which will then reshape their humanity and personhood, as it does ours).

We need positive stories from people who haven’t been ‘supressed,’ but instead have found fulness and flourishing in giving their lives, and sexuality, to Jesus, and who have then found love, and support, and understanding in Christian communities. But at the same time that we need these stories, our ‘soft’ conversion therapy practices and barrier erecting, and marginalisation of these brothers and sisters means they are unlikely to speak up in our defence. This feels like when we poured a bunch of social capital (and actual capital) into stopping our same sex attracted neighbours calling their relationships marriage (an expression of a fundamentally religious conviction), and then when we lost, we turned around and asked for our religious freedom to be protected. We live by the sword, we die by the sword.

We’ve still got a long way to go on this. We’re accidentally eradicating those LGBTIQA+ individuals in our midst, trying to hang on to Jesus and live obediently to what they believe he calls them (and us) to, while fighting to clear our name over trying to eradicate the homosexuality in those who’ve left our communities wounded.

Check out this stunning Twitter thread from Grant Hartley, a Side B Christian, yesterday on the way institutions like ours want to have our theological clarity and public statements cake, often involving debates about how such Christians can and should express themselves to exist in our communities on our terms, while then wanting such Christians to carry the weight of pastoral care for vulnerable LGBTIQA+ youth.

Had we been doing the work of ‘cleaning our own room’ first, we might have voices other than heterosexual cis-gendered males with institutional power speaking on this issue, where heterosexual cis-gendered males with institutional power have been precisely the problem in eradicating our social capital in the first place. We might even not have the problem of people being harmed and traumatised by the church, but rather, committed to the goodness of submitting one’s sexual desires to the desire for eternal oneness with Jesus, as his bride, the church.

Until we do the sort of internal reckoning and reform — experiencing the sort of ‘conversion’ — that is required for us to be properly caring for LGBTIQA+ adults voluntarily participating in our communities, and supportively point them to Jesus, and transformation coming through union with him, through loving him above all other loves, we have almost no credibility when it comes to our claims to be caring well for vulnerable youth in our communities, and governments in this secular age is going to keep trying to intervene on their behalf.