Over summer I read two fascinating books that got me thinking about the role of the ‘physical’ commons; public space, and what it means that public space is now ‘privatised’ in that people pay money to bombard us with messages via outdoor advertising, and screens, and ever more invasive techniques to get us to buy things or see the world a particular way. This is never more truly pronounced than in an election campaign, but it’s actually much more sinister apart from those campaigns (which claim to be about the ‘public good’ of democracy and aiming to somehow help inform our choice as we ‘shape the public life’ of our community).

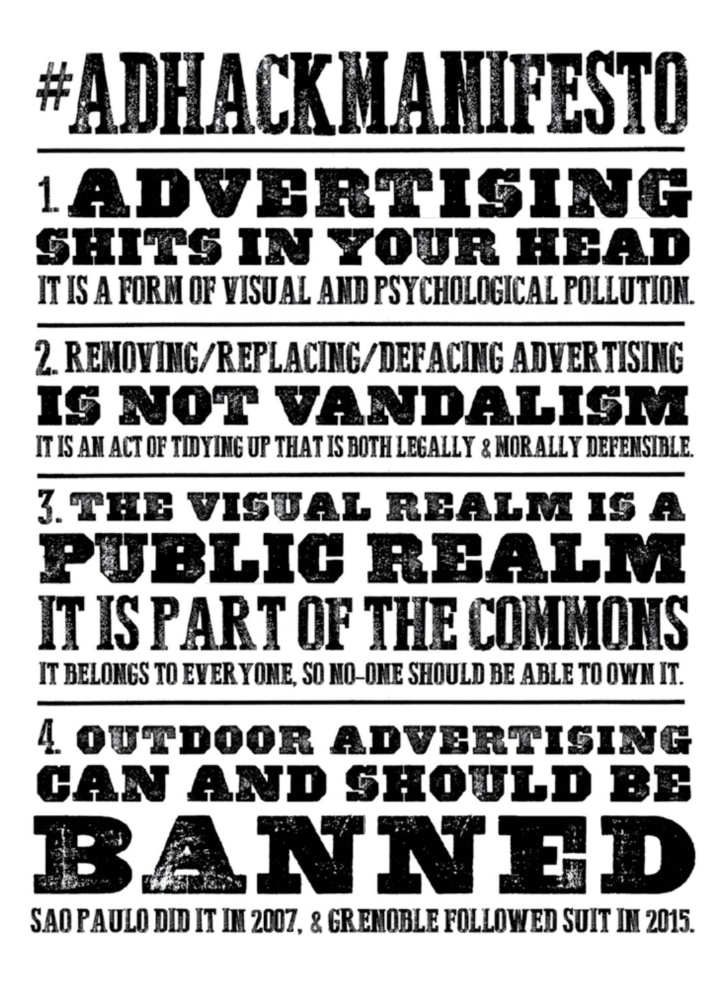

One book was about how to cultivate an ethic of attention via embodied practices and deliberation — Matthew Crawford’s The World Beyond Your Head: How to Flourish in an Age of Distraction, the other was a manifesto for public space activism (graffiti etc) called Advertising Shits In Your Head (free ebook). In one passage, Crawford describes heading to an airport and being bombarded, from start to finish, by advertising — even on the trays you put your odds and ends on as they pass through security — everywhere is ‘noisy’, space everywhere is ‘commoditised’, except where you pay for it not to be — the lounges…

“Silence is now offered as a luxury good. In the business-class lounge at Charles de Gaulle airport, what you hear is the occasional tinkling of a spoon against china. There are no advertisements on the walls, and no TVs. This silence, more than any other feature of the space, is what makes it feel genuinely luxurious. When you step inside and the automatic airtight doors whoosh shut behind you, the difference is nearly tactile, like slipping out of haircloth into satin. Your brow unfurrows itself, your neck muscles relax; after twenty minutes you no longer feel exhausted. The hassle lifts. Outside the lounge is the usual airport cacophony. Because we have allowed our attention to be monetized, if you want yours back you’re going to have to pay for it. As the commons gets appropriated, one solution, for those who have the means, is to leave the commons for private clubs such as the business-class lounge.”

This made me think not just about what an uncontested, non-privatised commons would look like (Crawford says public space should ultimately be as freely available as oxygen), but about how to advance what I believe is the public good of the Gospel apart from these commercial pressures (or what I would put into public space to grab the attention of a passer by, for their good).

Advertising Shits In Your Head is a fascinating anarchist text that had me thinking of all sorts of ‘reclaiming the commons’ campaigns that would be, I think, basically illegal. I’ve often noticed sticker bomb campaigns on pedestrian crossing/traffic light poles in the city and wondered about a ‘sticker bomb the Gospel’ approach to getting Jesus into the public psyche, or conversation. I wondered for a while if appropriately submitting to authorities, if one believes that the commons should be free not controlled by private interests, is not to not claim a presence, but to pay the fine (or do the clean up time) for participating in a conversation aimed at reclaiming the commons. I think I’ve decided to err on the side of caution on this front… but it did get me thinking; what would I use to draw the attention of the average, distracted, passer by on the streets (or in the ‘virtual commons’ of, say, the Facebook news feed (though this one requires paying for presence, ultimately becoming part of the problem (though offsetting that by offering something that one believes is genuinely a source of ‘human flourishing’ or a social good (less than can be said for Coca Cola (and when I was at uni we were told their ‘outdoor strategy’ is to get the brand in someone’s face close to ten times a day because science showed that was an effective ‘implanting’ tipping point that would increase the chances of prompting a purchase).

Advertising Shits In Your Head is a manual for ‘subvertising’, claiming “the modern subvertising movement has consumerism as its target. Many practitioners present their work as explicitly anti-capitalist and almost all object to outdoor advertising as a form of propaganda,” it quotes a guy campaigning to outlaw public advertising, Jordan Seiler, saying “Our acceptance of advertising is testament to how much advertising in general has infused itself into our lives and we consider it to be a medium that is inescapable and just inherently part of the capitalist system…” It says (and I find it hard to disagree):

“It’s not that propaganda, public relations, advertising, or the intersections of all three are inherently evil, it is rather that the system they have been so adept at promoting throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries is responsible for economic crises, resource wars, widening inequality, and perhaps most alarmingly, environmental destruction on a global scale. Subvertisers can justifiably argue that propaganda is, once again, marshalling millions to their deaths.”

In short, in theological terms, public advertising is often a tool of ‘babylon’ luring us away from the flourishing life that is found in relationship with our creator, through Jesus, and towards idols that are disappointing and destructive. You don’t need that Tag Heuer watch; nor do you need to desire it.

In the political theology essay I posted yesterday I made the case that Christians should be disruptors of beastly systems — including, to some extent, the sort of ‘capitalism’ built on the idea that we should define our humanity in terms of consumption and the pursuit of happiness through products and services that we pay for and develop using technology (so that we become little cogs in an economic machine). It seems to me that advertising plays a pretty substantial part in keeping us there because it is so rarely, if ever, targeted at the public good rather than some agenda to serve a private good (even doing so by creating a perceived ‘public good’… and even public service announcement style ‘advertising’ from governments is so often coupled with the agenda of winning re-election not by leading a conversation about public good, but by jumping on board such a conversation once the political pulse has well and truly been checked). I’m also a former ‘propagandist’ (at least an ethical one, I hope, and perhaps not entirely ‘former’), and I think there are methods or techniques of ‘propaganda’ that can genuinely put to good use for the sake of the common good so long as they seek persuasion without manipulation or coercion (part of the topic I explored in my thesis about how to ethically and excellently communicate/engage in the public square with the Gospel).

So as I read these books I wondered: what would I do to ‘subvert’ the narrative of advertisers and their claiming of ‘public space’ for their private interests? If I was to invade that space in order to subvert those intentions for the good of my neighbours, what would I do? The answer, of course, is Jesus — who so utterly is at odds with the agenda of ‘Babylon’ or the self-gratifying propagandist, and who does offer, if the Gospel is true, ultimate satisfaction and the ‘abundant life’. I wondered, what would I turn into a sticker to slap up on public spaces, or use as a little ‘tear off’ poster on a community noticeboard? What would I hope might realistically evoke a sense of curiousity, and once evoked, how would I move that curiousity to action (or what marketers call ‘conversion’)? So I started trying to write a website inviting people to try Jesus, and to do it immediately. I wanted to explore the connection between Jesus and the ‘public good’ or the flourishing life, and so focus on the truth, goodness, and beauty of the life, example, and teaching of Jesus (the Gospel) and the life it produces; it’s not that I don’t want to talk about sin and judgment (those are inescapably part of that life), but I want repentance to be more about turning to Jesus than away from sin… and then I wanted the steps towards ‘trying Jesus’ to be more about experiences that give the Gospel plausibility, and more about the heart than the head (though not not about the head — given that those intuitions and emotions are also produced by the brain in response to stimulus and to some extent thought, and also the evidence for Christianity is quite compelling).

So I started a website: tryjesus.today

It’s not complete. It will hopefully evolve. I’d love it to include short video testimonies from people who’ve decided to give Jesus a try (maybe that’s you?), and I’d also love your feedback about what you reckon works, and what doesn’t… and how to do this act of ‘subvertising’ without undermining the message of the Gospel.