News broke yesterday that ISIS had beheaded 21 Egyptians for being “people of the Cross.” Images from the dramatic and disturbingly choreographed and colour coordinated public statement are circulating around the internet, but I have no desire to aid the spread of ISIS propaganda, so you won’t find them here.

What you will find is some further processing of these events, consider this the latest in a series of thinking out loud, which started with the “We Are N” post, and incorporates the post responding to the siege in Sydney’s Martin Place, and the post responding to the Charlie Hebdo shooting in Paris.In the first, I explore the relationship between Christianity and martyrdom — something this post will unpack a bit more. In the second I suggest that one of the things we need to keep recognising in this ISIS situation is that people are motivated by religious beliefs, and that even if ISIS does not represent mainstream Islam (which, by all accounts from mainstream Islamic clerics, it does not), it does represent a form of religious belief. This is a case made in this article from The Atlantic: What ISIS Really Wants. In the third, I suggest that the Cross of Jesus is the thing that should shape Christian responses to brokenness in the world, our ‘religious motivation,’ and that this is the key to responding well to radical religious violence.

This latest horror brings all of these threads together.

I don’t know how you process events like this — it probably depends greatly on your vision of the world, of life, and death. I’m still figuring out what an appropriate response to this looks like. Part of me is just an emotional ball of anger at the world, perhaps even at God, a raging, fist shaking lament at the injustice in yesterday’s events. Part of me cries out for the sort of “justice” that the Egyptian government has promised to exact, but I’m not sure that actually solves anything (it may even make things worse). Part of me believes that this event is an incredibly clear picture of the vision of hope held out by two different religious outlooks — involving two different sorts of “fundamentalist.”

If you’re not a Christian (or a Muslim) then you may look at this event, and other executions carried out by ISIS, as just another mark chalked up on the wall in a battle between two groups fighting over whose imaginary friend has more power, if you’re a mainstream Muslim you may be horrified that, once again, you’ll be called on to explain the actions of people who have taken up the name of your faith and used it to destroy others. If you, like me, are a Christian, you might be trying to figure out how to parse out the simultaneous shock and horror at this situation, the turmoil in your own inner-monologue as you grapple with the question “what if my faith were tested like this,” and, perhaps you might worry that you have what some (even you, as you mull it over) might consider a perverse sense that these Christians are heroes, whose faith encourages you in your own suffering, or lack of suffering.

Hopefully, the universal human response — beyond the response of those carrying out the killings — is one that involves the realisation that these events are a very loud, very clear, indicator that something is very wrong with this world. It may be that you think religion, and violence like this, is at the heart of what is wrong with the world, or it may be that this brokenness we see in the world causes us to seek after God, forcing us to work through the different pictures of God we find in different religious frameworks.

This particular story — the execution of 21 “people of the Cross” is actually a picture of two religious fundamentalists acting entirely consistently with the fundamentals of their beliefs (not necessarily as fundamentalists of everyone who chooses a similar label — but actions that are consistent with the motivations of the people involved).

In any of these cases you might wonder what motivates a person to act like this — as a religious fundamentalist — either to carry out such atrocities on fellow humans, or to not renounce your faith in the face of such an horrific, violent, death? In both cases the answer is caught up with the religious notion of hope — a vision of the future, both one’s own, individual, future beyond death, and the future of the religious kingdom you belong to. This hope also determines how you understand martyrdom — giving up one’s own life (or taking the lives of others) in the name of your cause (or against the name of theirs).

It’s worth calling this out — making sure we’re sensitive to the distinction between this Islamic vision for the future, and the mainstream, because it’s in the actions of believers, on the ground, that we are able to compare the qualities of different religious visions of, and for, the world.

What we see in events like this is a clash of two religious visions for the world — a vision for hope secured by powerful conquest, the establishment of a kingdom, and martyrdom for that cause, and a vision for hope secured by God’s sacrifice for us, and his resurrection, which involves a kingdom established by the Cross, for ‘people of the Cross.’ This first vision is the motivation at the heart of the ISIS cause, and the latter is at the heart of a Christian view of martyrdom and hope. There’s also, potentially, a chance to examine a secular vision for the world — which typically involves peace, or an end to conflict (perhaps especially religiously motivated conflict).

Every world view — whether religious, or secular, grapples with this brokenness, and aims to find a path towards an unbroken world. Clashes of world views — like this one, give us opportunities to examine what world view actually provides a meaningful path towards such a transformation. Such a path is fraught, I don’t think there are many solutions that don’t perpetuate the brokenness. I’ll suggest below that it’s only really Christian fundamentalism that will achieve this, the Atlantic article articulates the problem with potential non-religious/secular solutions, especially the military option.

“And yet the risks of escalation are enormous. The biggest proponent of an American invasion is the Islamic State itself. The provocative videos, in which a black-hooded executioner addresses President Obama by name, are clearly made to draw America into the fight. An invasion would be a huge propaganda victory for jihadists worldwide: irrespective of whether they have givenbaya’a to the caliph, they all believe that the United States wants to embark on a modern-day Crusade and kill Muslims. Yet another invasion and occupation would confirm that suspicion, and bolster recruitment. Add the incompetence of our previous efforts as occupiers, and we have reason for reluctance. The rise of ISIS, after all, happened only because our previous occupation created space for Zarqawi and his followers. Who knows the consequences of another botched job?”

Christians believe we are saved, and the world is transformed, by martyrdom — but not our own

These 21 Egyptian ‘people of the Cross’ are not saved by their martyrdom.

They do not have extra hope because of the way they die.

They may have died because of their hope — hope placed in Jesus, but as Christians, our hope is not in our own lives, or our own deaths, as contributors to the cause of God’s kingdom, but rather, in God’s own life, and death, in the person of Jesus.

Jesus’ death. Not our own. Is where Christians see the path to paradise.

This produces a fundamentally different sort of kingdom. It produces a fundamentally different sort of fundamentalist. A person living out the fundamentals of Christianity is a person who is prepared to lay their life down as a testimony to God’s kingdom, out of love for others — to lay down one’s own life for the sake of our ‘enemies’ and our neighbour. Because that is what Jesus did, for us.

Here’s what Paul says is at the heart of Jesus’ martyrdom. His death. From his letter to the Romans.

“But God demonstrates his own love for us in this: While we were still sinners, Christ died for us”

Since we have now been justified by his blood, how much more shall we be saved from God’s wrath through him! For if, while we were God’s enemies, we were reconciled to him through the death of his Son, how much more, having been reconciled, shall we be saved through his life!

Later, in the same letter, Paul shows how this martyrdom becomes the paradigm for a Christian understanding of life, death, and following God. A very different outlook, and a very different fundamentalism, to what we see in ISIS.

“Therefore, I urge you, brothers and sisters, in view of God’s mercy, to offer your bodies as a living sacrifice, holy and pleasing to God—this is your true and proper worship…”

And a little later in the same part of the letter, we get an outline of a Christian response to these truly evil, and horrific, killings — and, indeed, to all the evil and brokenness we see in the world. When we live like this, we live out our hope, we become living martyrs, embodying the values of our kingdom and following our king.

“Love must be sincere. Hate what is evil; cling to what is good. Be devoted to one another in love. Honor one another above yourselves. Never be lacking in zeal, but keep your spiritual fervor, serving the Lord. Be joyful in hope, patient in affliction, faithful in prayer. Share with the Lord’s people who are in need. Practice hospitality.

Bless those who persecute you; bless and do not curse. Rejoice with those who rejoice; mourn with those who mourn. Live in harmony with one another. Do not be proud, but be willing to associate with people of low position. Do not be conceited.

Do not repay anyone evil for evil. Be careful to do what is right in the eyes of everyone. If it is possible, as far as it depends on you, live at peace with everyone. Do not take revenge, my dear friends, but leave room for God’s wrath, for it is written: “It is mine to avenge; I will repay,” says the Lord. On the contrary:

“If your enemy is hungry, feed him;

if he is thirsty, give him something to drink.

In doing this, you will heap burning coals on his head.”Do not be overcome by evil, but overcome evil with good.

This is a picture of Christian fundamentalism. It’s an exploration of what it looks like to be people of the Cross.

Bizarrely — the horrific killings ISIS is carrying out, especially as they execute ‘people of the Cross’ actually serve Christians who are looking to express our own hope as we offer ourselves in this way.

We bear witness to his martyrdom in the way we lay down our lives for others — even as we live. Christian martyrdom involves bearing faithful witness to the one martyr who gains access to the Kingdom through self-sacrifice. When we get this picture we can be confident that God’s power rests in our weakness, rather than our displays of strength. This produces a fundamentally different political vision and approach to life in this world, and the comparison is never starker than it is when it is displayed in the face of a religious ideology like that of ISIS, which mirrors, in so many ways, the religious ideology of the Roman Imperial Cult, and its persecution of the earliest people of the Cross.

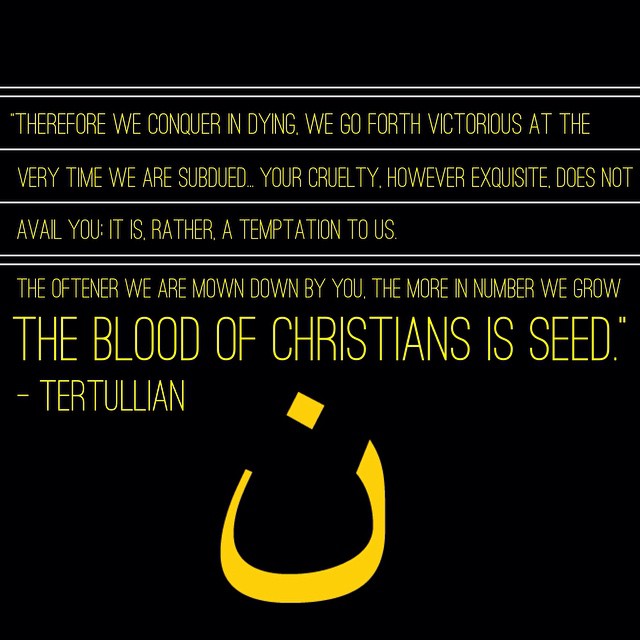

This is the hope one of the earlier Christians, Tertullian, articulated to the Roman Emperor, as he called on them to stop executing Christians, his argument, in part, because killing Christians was not serving the Roman Empire, but God’s empire. He wrote a thing to Rome called an Apology — a defence of the Christian faith, and the place of Christianity within the Empire. It’s where the quote in the image at the top of the post comes from. This quote (this is the extended edition).

“No one indeed suffers willingly, since suffering necessarily implies fear and danger. Yet the man who objected to the conflict, both fights with all his strength, and when victorious, he rejoices in the battle, because he reaps from it glory and spoil. It is our battle to be summoned to your tribunals that there, under fear of execution, we may battle for the truth. But the day is won when the object of the struggle is gained. This victory of ours gives us the glory of pleasing God, and the spoil of life eternal. But we are overcome. Yes, when we have obtained our wishes. Therefore we conquer in dying; we go forth victorious at the very time we are subdued…

…Nor does your cruelty, however exquisite, avail you; it is rather a temptation to us. The oftener we are mown down by you, the more in number we grow; the blood of Christians is seed.

This is what Christian fundamentalism looks like. We need more Christian fundamentalists. More Christian martyrs. More people expressing this hope in how they live and die.

This, amongst my prayers of lament for those killed as people of the cross, and in the face of the brokenness of the world, and the horror of the Islamic State’s vision of ‘hope,’ is what I’m praying. That God will bring justice for these killings, but that he will also bring hope through them, as people catch sight of the sort of lives lived by Christian fundamentalists. People of the cross.

I want to be that sort of person — a person of the cross — to be known that way, this is one of the realisations I have come to while processing these killings.

It is only when we whose hope, whose visions of the future, are shaped by Jesus live as Christian fundamentalists, in the Romans 12 sense, that we have any hope of really, truly, presenting the Christian hope for the world — God’s hope for the world — to others.

It’s the only real hope we have of fighting other visions for the future, or breaking the cycle of brokenness.

What other response won’t just perpetuate feelings of injustice? What other responses have any form of justice that doesn’t simply create another perpetrator of injustice? Visions of justice that don’t involve this sort of Christian fundamentalism — giving up one’s ‘rights’ for vengeance simply create a perpetual system of perpetrators. This is perhaps seen clearest as we see boots on the ground (Egypt) or off the ground (The US) in secular visions of the future — military responses to ISIS, and in the actions of ISIS itself. Violence begets violence. Ignoring violence also begets violence. Something has to break that cycle — and the Cross, and the people of the cross, Christian fundamentalists, provide that circuit breaker. The message of the Cross also provides the path to paradise, the path to a restored relationship with the God who will restore the world, and the path to personal transformation both now, and in this transformed world. That’s a vision of the future I can get behind.