It seems we’re at a bit of a crossroads in the Australian evangelical church at the moment – once we recognise that the church isn’t really growing – do we throw our lot in with Spurgeon, or with Augustine… For many in our scene – faithful preaching from the pulpit is the ultimate panacea – and if the church isn’t growing then it doesn’t matter, so long as we’re faithful, or perhaps a lack of growth is a sign of some lack of faithfulness…

I reckon the problem is that many of us have conflated “faithful preaching of the gospel” with “expository preaching on a Sunday” – and we’ve pretty much checked our responsibilities in at the door at that point. I’m not going to argue against expository preaching – because I think it is part of faithfully preaching the gospel – but I wonder if we’re missing two-thirds of the persuasion triangle… We seem hesitant, or suspicious, of anything other than unadorned words – be it emotive production values or anything that by itself would be manipulative, or an emphasis on the sort of life and good works we should be producing outside of the pulpit… Part of this has been from a desire to respond to the imbalance of the pentecostal movement on one hand, and the social gospel driven ecumenical movement, which focused solely on “liberating the oppressed” because nobody could agree on what the gospel actually is, on the other. But we’ll get to that when we get to the triangles below…

On the merit of “Egyptian Gold”

I read this stirring Spurgeon quote about preaching that Justin Taylor shared a couple of days ago, especially these bits:

“Are you afraid that preaching the gospel will not win souls? Are you despondent as to success in God’s way? Is this why you pine for clever oratory? Is this why you must have music, and architecture, and flowers and millinery? After all, is it by might and power, and not by the Spirit of God? It is even so in the opinion of many.”

…”I have long worked out before your very eyes the experiment of the unaided attractiveness of the gospel of Jesus. Our service is severely plain. No man ever comes hither to gratify his eye with art, or his ear with music. I have set before you, these many years, nothing but Christ crucified, and the simplicity of the gospel; yet where will you find such a crowd as this gathered together this morning? Where will you find such a multitude as this meeting Sabbath after Sabbath, for five-and-thirty years? I have shown you nothing but the cross, the cross without flowers of oratory, the cross without diamonds of ecclesiastical rank, the cross without the buttress of boastful science. It is abundantly sufficient to attract men first to itself, and afterwards to eternal life!”

…In this house we have proved successfully, these many years, this great truth, that the gospel plainly preached will gain an audience, convert sinners, and build up and sustain a church.

There is no need to go down to Egypt for help. To invite the devil to help Christ is shameful. Please God, we shall see prosperity yet, when the church of God is resolved never to seek it except in God’s own way.

There is much to like in Spurgeon’s quote – the church is God’s agent in the world and its job is to promote, proclaim, declare, whatever verb you like, the wonder of the Gospel of Jesus Christ. That’s our mission, and arguably how we worship.

But there are a couple of things that rankle me in this quote – while I agree that the gospel requires words – because it is the story of God’s word made flesh…

- I still can’t help but think that the reduction of our mission to just words misses the point of both the actions that the written accounts we call gospels contain, and the strong links made between the lives we live, the good we do, and the love we give and our testimony to the world (so to provide a sample of from three different New Testament’s authors – John 13:35, 1 Cor 10:33, 1 Peter 3:8-16). Interestingly, Augustine suggests that the good we do should be to the end of seeing people come to know God…

- I don’t understand the assumption that the Spirit can’t work through architecture, music, flowers, or even millinery – surely the Spirit doing so would be a greater testimony of his power, not lesser. Surely if there is a milliner, or flower arranger, in your congregation they can find some use for their profession as part of the body, to point people to Jesus – these things can’t replace word ministry but word ministry doesn’t need to happen in a cultural vacuum (and the right balance is important). I like Luther’s potentially pseudopigraphic “make a good shoe and sell it for a fair price” quote at this point…

- I can’t figure out why “word ministry” as in the promotion of the Gospel should be limited to the spoken word in a way that rules out using the “gold of the Egyptians” – or without the metaphor – the good parts of the created order that can be applied to gospel ministry and declaration of truth. Music, video, the arts – all of these can be used as “word” ministry – they just lean heavier towards pathos than logos when it comes to the persuasive act.

- This displays a limited doctrine of creation – one I’ve been guilty of in the past when it comes to free range eggs (and the environment) – the way we treat creation and how we use it is also part of our testimony – and this includes the way we think of the arts, and things that people make as part of our stewardship of creation and desire to bring order to it… as an aside: I don’t think the way “creation” and “redemption” are as separate as some people want to suggest (there’s a bit of a debate about this) – I now think redemption, and God’s mission, encompass creation – and how we use it – but “redeeming creation” is not an “end,” it’s a means to support the ultimate end – our mission to redeem people.

In fact – on the second point – what we do with the “gold” we find – or the goodness of creation – is an incredibly strong part of our testimony.

The “receive, redeem, reject” paradigm for culture that has been made popular by Keller, Driscoll, et al is pretty useful – and it works with the plundered gold analogy that Augustine ran with…

If the gold of Egypt is some sort of “truth” – a “created order” thing, being used in a cultural way – perhaps, for the purpose of this post, a persuasive technique, or musical style… it seems to me there are four options for this thing:

1. Leave it in Egypt – assuming the gold itself is inherently bad – because people use it to make idols.

2. Bring it with you, as is, or make it your own idol – like a golden calf, at the foot of Sinai.

3. Bring it with you, because gold is beautiful – recognise its goodness without worshipping it – music whether written to honour God – like Bach, or written as a recognition of the way ordered sounds can work together to create pleasure – captures something of the goodness of creation, as music.

4. Bring it with you, use it to glorify God – build the temple out of it, artistically, with sculptures. People will then both understand a good God made it, and understand that this Good God is Yahweh, who reveals himself in creation, and the redemption of creation.

The first seems to be Spurgeon’s approach when it comes to what happens in church, the fourth seems to be what Augustine advocates… it’s no secret that I think Augustine is right – my masters project is going to be an application of his principle to modern communication theories. Here’s the money quote…

“…all branches of heathen learning have not only false and superstitious fancies and heavy burdens of unnecessary toil, which every one of us, when going out under the leadership of Christ from the fellowship of the heathen, ought to abhor and avoid; but they contain also liberal instruction which is better adapted to the use of the truth, and some most excellent precepts of morality; and some truths in regard even to the worship of the One God are found among them. Now these are, so to speak, their gold and silver, which they did not create themselves, but dug out of the mines of God’s providence which are everywhere scattered abroad, and are perversely and unlawfully prostituting to the worship of devils. These, therefore, the Christian, when he separates himself in spirit from the miserable fellowship of these men, ought to take away from them, and to devote to their proper use in preaching the gospel. Their garments, also —that is, human institutions such as are adapted to that intercourse with men which is indispensable in this life — we must take and turn to a Christian use.”

There really is no “Egyptian Gold” – but rather an Egyptian use of Gold, that may or may not be redeemable. This is demonstrably the case if we believe that every idol results from taking something good that God has made and using it in wrong ways.

On “faithful preaching” and equilateral triangles

But all this got me thinking about “faithful preaching”… and triangles.

If the following linked premises hold true:

- Preaching must involve the faithful articulation of the gospel. I’m with the Bible, the reformers and the Westminster Confession on this – for a church to be a church, it needs to be a gathering of people united by the gospel of the Lord Jesus, who are proclaiming the gospel through preaching and the sacraments.

- Our “preaching of the Gospel” can’t just be words. It has to include words – so Francis of Assisi is still wrong – but those words need to be backed up by action. How the church lives and loves its community is part of the package of faithful gospel preaching… because teaching is more than words.

- Paul’s call to “imitate him, as he imitates Christ” (1 Cor 11:1) is a bit of a unifying principle delivered to a church fractured over preaching styles (the conflict he addresses earlier in the letter) – where imitation was a key part of first century oratorical competition (so, for example, Cicero bemoans poor choices about who and what young orators imitate and pushes for an imitation of substance over style).

- Paul, in both 1-2 Corinthians, champions an approach to preaching that includes the embodiment of the cruciform (cross-shaped) life as the key aspect of this imitation (you’ll have to read my essay on Corinthians to find out why I think this)

- Preaching is an act of persuasion (no doubt governed by the work of the Spirit – I’d argue, like Augustine, that rhetoric works because it recognises a truth about the order God has created in the world, particularly how human minds work).

- Faithful preaching is more than what is said from the pulpit, but is how a preacher, and by extension the church, as a whole, lives as the Body of Christ in their time and place.

There’s something nice and Incarnational about all of this that I’m increasingly appreciating…

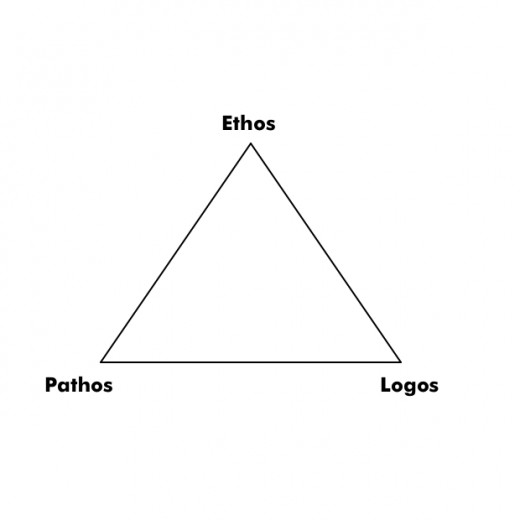

But if these points are true – then we can kind of understand “faithful preaching” using an Aristotelian framework, which includes logos, pathos, and ethos – with the type of life the preacher lives (ethos) being a decisive communicative act – serving to either emphasise or undermine the “pathos” or “logos” (ie the content of the preaching)… Which is where the triangles come in…

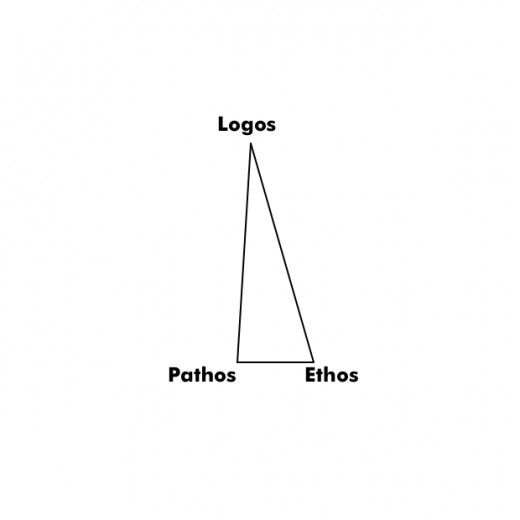

I’d argue that part of the mix which is limiting the growth of our branch of the church is that we’re so cerebral and logos driven in our approach that we’re relying almost entirely on our ability to persuade solely by reason (I’m not suggesting the Spirit can’t work through this – simply that it might be true that God has created us to respond to pathos and take note of ethos as well – and that we’ve been instructed to employ those aspects as part of our “preaching” more than we might at present in our gatherings and the rest of our life as a church).

It’s hard to make generalisations here… and I’m reflecting a little on my experience in some churches that were actually growing as a result of faithful and engaging Bible teaching – and some attempt to figure out how to engage with the world around us (I don’t think they’re just doing what Spurgeon says is all they need to be doing – they typically also have excellent music, well thought out architecture, and other bits and pieces) – but also on my observations of the churches that I’ve been part of that seek to imitate the logos aspect of those churches without necessarily investing heavily into pathos in a way that treats each place and people group as different…

I’m also reflecting a little on my training, the things that have been emphasised as I grew up in evangelical ministries in Australia including my churches, AFES, other groups I’ve been part of, and my experience at theological college. All of these groups require a certain threshold for “character” when it comes to involvement, but I don’t think ethos – which I’m defining as how to live in the world in a winsome and persuasive way that backs up my words – has ever been the focal point of the training I’ve received.

I’ve been pretty well equipped with the logos stuff… I think, like Spurgeon, we’ve been pretty suspicious of pathos too, because without logos it can be manipulative and lacking in substance (and we’ve seen that a little in the worship wars and the Pentecostal movement), though I think being “winsome and gracious” in how you speak is a mix of pathos and ethos.

I suspect the lack of focus on ethos is because ethos will ultimately look, without the logos, like the social gospel stuff we’re all so keen to avoid.

And now. For the visual learners and thinkers… a triangular approach to this issue.

This is a triangular picture of Aristotle’s approach to rhetoric. It’s an equilateral triangle, and represents all these aspects being held nicely in balance – I suspect this is the model for faithful preaching – because I think Aristotle has rightly recognised the way humans are persuaded of truths.

If this is a truth about the way people, and creation, works – then we should expect to see some fruits of it in terms of growth, assuming that the Holy Spirit works, in some way, consistently with the created order that God declared to be good. Perhaps even by helping us see that order in a way that guides our participation in the world.

This is my caricature (thus it is a little reductionistic) of the emphasis I think exists in our evangelical circles, it’s not without pathos or ethos – but logos is heavily emphasised.

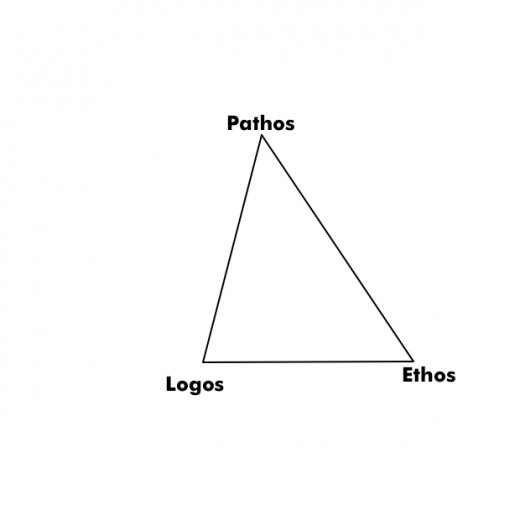

This is my caricature of the emphasis in more charismatic churches… My guess is that these churches are growing faster than those in the evangelical tradition because their triangle is a little closer to being persuasive – while they don’t necessarily place a heavy emphasis on solid teaching, they tend to, as a generalisation, be more interested in social justice type stuff, and much better at appealing to the emotions via their production quality, use of music, style of music, etc… Though their teaching is a little shallower than we might like, and occasionally just plain wrong in terms of what promises are fulfilled now for Christians, and what is still to come – it’s generally recognisable as Christian preaching, in that the Lordship of Christ is foundational.

And this is my caricature of the emphasis in liberal churches where the emphasis is on bringing transformation to the world, and liberating the oppressed – rather than articulating any actual definitive truth. There’s a complete lack of balance here – and depending on the churches in question, the lack of anything remotely like logos translates to a lack of moderating influence on what constitutes faithful gospel shaped pathos or ethos, which is why I think the liberal church is shrinking faster than any other variety.

So, I reckon Spurgeon is right – I think all that is required for the church to grow is faithful, Christ centred, gospel preaching – but I think that encompasses more than the delivery of a logos-heavy presentation from the pulpit, it’s got to involve using the goodness of creation to point people to the creator of that goodness, through the right use of pathos – music, art, and an understanding of how to stir the emotions, but it’s ultimately got to be matched with the type of ethos outside the pulpit that lends weight to our words when we talk about God loving people.