Two cool things, slightly related.

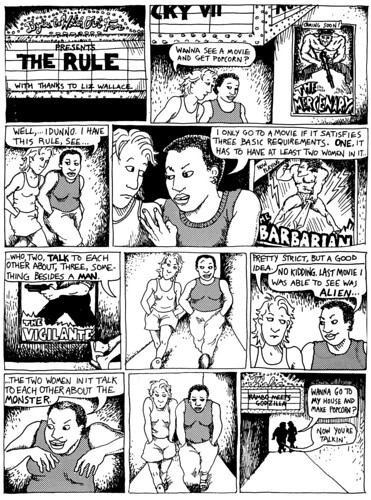

The first is the Bechdel Test – which is a test devised by a comic strip for lesbian feminists. But is an interesting way to approach the film industry’s treatment of women.

To pass the test a movie must have:

(1) it has to have at least two women in it,

(2) who talk to each other,

(3) about something besides a man.

This site ranks cinematic releases according to the test (a surprising number fail).

Here’s the comic:

The second little tidbit is about characters in fiction for kids and young adults. There’s a magic formula of two boys to one girl that sucks in readers from both genders – get the balance wrong and you lose half the audience.

Ben Jeapes, under a nom-de-plume, wrote some books about vampires before that was cool (they’ve since been retitled and rereleased). In this post about that rebranding (which is a little cynical, which is funny). He makes the following observation.

“The three heroes stick to the magic Harry-Ron-Hermione formula for pre-teen adventures of 2 boys to 1 girl [though there is a guest extra girl in the second book]. This is because boys only want to read about boys whereas girls will read about either gender: so, you get a boy for the boys, a girl for the girls, and another boy to make up for the girl. Sad but true.”

Comments

That’s an interesting idea. It certainly rings Phantom of the Opera bells. Now I’m trying to think of other works that follow a similar line. Bridget Jones springs to mind. Could we count Shrek, Fiona and Donkey?

If you can count Becky Thatcher with Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn, there’s a possibility, but I think it’s tenuous. Oliver (Twist) and Fagin/Bill plus Nancy is also a bit of a stretch. As is To Kill A Mockingbird with Jem, Scout and Atticus or Boo Radley.

Narnia has two guys and two girls, so not quite. And there were lots of boys and not tons of girls in The Outsiders (definitely worth reading if you haven’t!). Robin Hood also has the lots of boys to not many girls ratio, which at least bears out the “boys need boy characters to stay interested” idea.

Musicals tend to be full of numbers of both sexes (Grease, Cats, West Side Story, etc.).

Shakespeare also isn’t a great example (Hamlet, Macbeth and Lear don’t really bear this out), though there’s definitely a case for Othello, Iago and Desdemona and possibly some others.

A lot of the classic literature I can think of doesn’t really support it explicitly either. (Wuthering Heights, Jane Eyre, A Tale of Two Cities, Moby Dick (granted, haven’t read it — but I don’t think it does), 1984, The Scarlet Letter, Pride and Prejudice, Tess of the D’Urbervilles, Old Man and the Sea, Farewell to Arms, Gulliver’s Travels, Heart of Darkness, etc.)

My guess is there’s something to it, but not everything — that it’s a good, proven formula for a good story, but there are also lots of others (say, for example, that whole one guy to one girl ratio).

Very interesting, though; thanks for bringing it up!!

Interesting exercise Kim, but I wouldn’t call most of your examples children’s or young adults fiction – more literature. I think he was more thinking pop-fiction, most Enid Blyton mysteries go close. I wonder at what point in literary history the “rule” kicked in.

ah, yes, i think read over that “pre-teen” bit — still fun though!