This is an amended version of a sermon I preached at City South Presbyterian Church in 2022. If you’d prefer to listen to this (spotify link), or watch it on a video, you can do that.

Origin stories are helpful if you want to understand the world you live in — and how to live.

If you want to understand why Gotham city has become dark and scary; why the Joker and other over the top villains are running around causing chaos; why they have responded to the Batman’s over-the-top embodiment of fear by fighting fire with fire; you have to find yourself back in a dark alley where that batman’s alter-ego, Bruce Wayne, witnessed his parents being murdered… And an earlier experience young Bruce had with scary bats in a cave.

So many of our fictional worlds are built on origin stories that aren’t just about a key person, but explain why the world is the way it is; it’s not just fictional worlds shaped by an origin story; we humans are shaped by our own origin stories. This is part of what drives the popularity of genealogical research — learning about our family history so we can understand the present on an individual level, while at a societal level the lives we live together are often shaped by common stories we believe about the world. if you believe humans emerged from purely natural processes in a world that is closed off to any god or gods, then that’s going to shape how you use your body and use the natural world world….

In this series we’re going to tackle the way the Genesis origin story does — or doesn’t — relate to a modern, scientific, secular view of reality — whether that’s a young earth or old earth version of that science story. Whatever you believe about the science story, this shapes the way Christians live in the world and how we approach science and decision making (note: there’s an observable link between young earth creationism and skepticism about the science behind anthropogenic climate change).

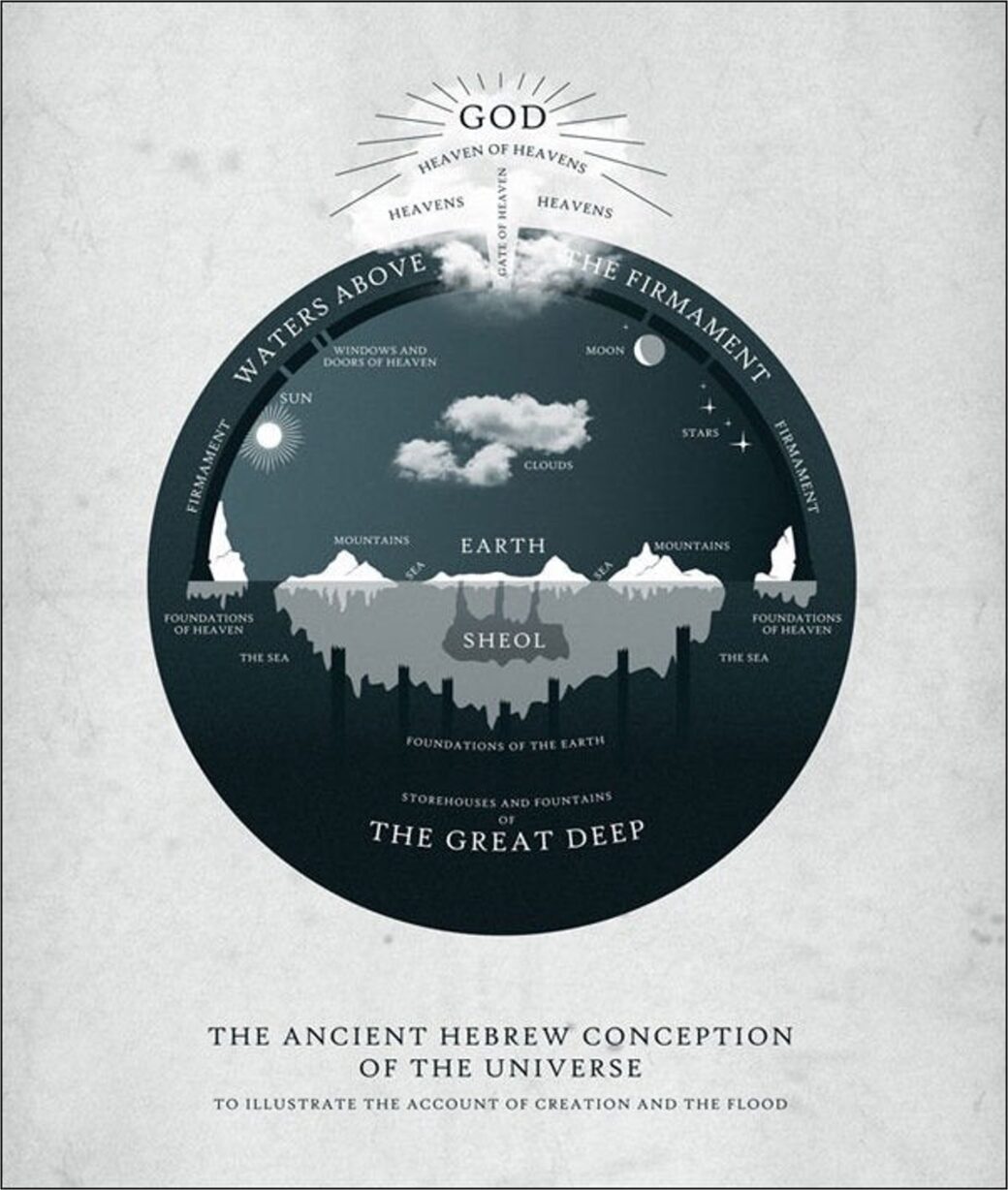

The Bible’s origin story doesn’t come from a modern view of the world; their concept of the physical world looked very different to the picture we gain from satellites looking back at the earth from orbit; the Old Testament vision of the cosmos has more in common with the stories of israel’s neighbours — the nations they interact with in the Old Testament — like Egypt, and Babylon.

It’s an origin story with a model of the universe at home in the ancient world — engaging with and critiquing ideas about God held by Israel’s neighbours. These were origin stories Israel was tempted to believe and live by as they were tempted by idolatry and the alternative vision of god, and the world, and the purpose of human life, offered by the stories and cultures around them. We have a good idea what these empires believed about the origin of the cosmos, and the purpose of human life, thanks to archaeological discoveries in the last 200 years; we can now read stories like Babylon’s Enuma Elish, or the Egyptian ‘Book of the Dead’.

As we work our way through this series we’re going to consider how this context might shape how we read the story — so that we’re asking the sort of questions the text itself might be answering. This isn’t because the genesis story can’t exist alongside science stories — whether old or young earth stories — it’s just that these stories aren’t what this origin story is about. We won’t get good answers in genesis unless we’re asking the right questions.

Our main guide for reading the Bible’s origin story isn’t going to be these ancient creation stories that are a reasonably recent discovery, but the way these origin stories — these chapters at the start of the Bible, unfold through the rest of the Bible.

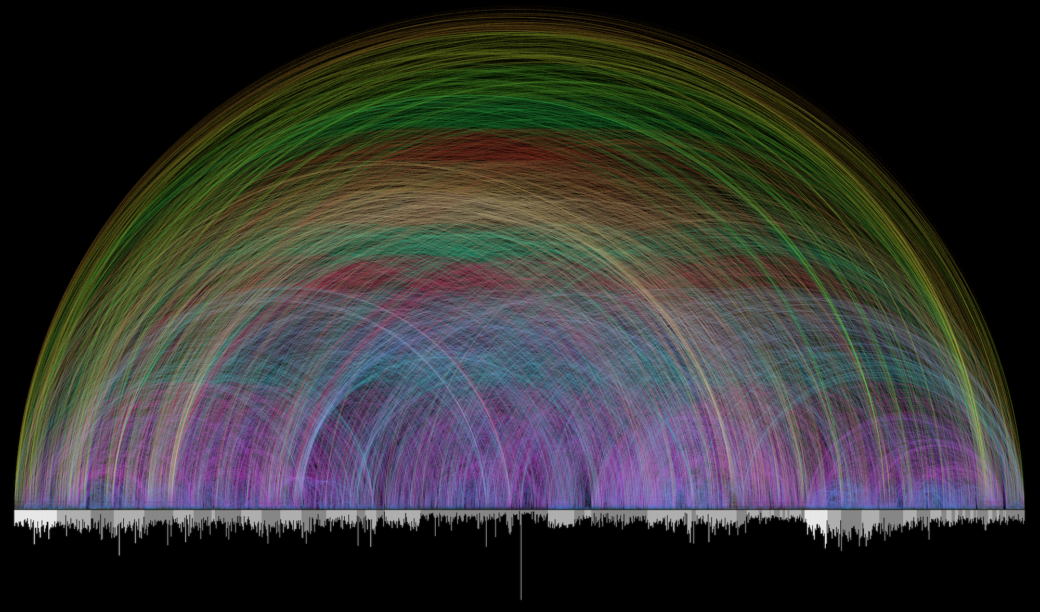

Here’s a picture of how hyperlinked the bible is — how many later books build on — by referencing — earlier books.

Source/Credit: Chris Harrison, BibleViz, Bible Cross References

The Bible is a rich tapestry — a library — that builds an internal and coherent understanding of the other books — not just through quotes — that this picture picks up, but through the building of themes and patterns and imagery that we pick up as we read.

So we’ll try to make sense of these chapters of this book by placing them in this context — and not just of the Old Testament, as though we’re the first hearers and readers of the story – but with the New Testament, as it’s fulfilled in Jesus. Because both Matthew’s and Luke’s Gospels locate the roots for the family tree of Jesus back in Genesis — tracing the line of seed — offspring — through to his arrival as the Son of Man and the Son of God.

Part of recognising that the Bible unfolds as one story and that this story shapes our lives as God’s people means considering how the story itself worked for people living that story along the way, throughout the family tree (or “genealogy”), considering, for example how the nation of God read, or told (prior to its final compilation), this story from “Abraham to David” (in Egypt, for example), from David to exile (in the land), or then during exile in Babylon. We know the united final form of the Old Testament history running from Genesis to 2 Kings was put together after those events ended. This challenges our modern readings of the text, confounding the categories we want to bring to the debate. The story has its own purpose, and its own context, in this bigger story — God’s story. It’s doing something very different to what we want it to do as modern humans with a view of the cosmos we build from satellite images.

Genesis tells us quite a lot about quite a lot of things; but perhaps primarily it is a story that reveals the nature and character of God to us, and grounds everything else in that act of revelation. We can make try to make it answer our questions, but often we get the subject wrong. Genesis frames our answer to questions around the nature of the universe and the nature of life within in it by placing reality — the heavens and the earth in their place as creations of a god who was and who is — before the heavens and the earth began. This is the scene set in the opening words of Genesis, where we’re told that in the beginning God creates the heavens and the earth (Genesis 1:1).

Now, some people see this as a heading that describes what’s going to happen in the rest of chapter one. For a few reasons, especially the long arch in that picture that goes from the beginning (Genesis) right to the end of the story (Revelation), I think this should be read as a statement that in the beginning god created these two overlapping realities — the heavens — his home, and the home of the spiritual beings in his heavenly host — and the earth —a home for humans and a host of animals.

The other thing to consider is that we jump to thinking of the whole globe viewed from a satellite, when we hear the word “earth,” but it’s literally “the ground” in the imagination of the ancient reader, who hasn’t sent a satellite up into space yet, and who knows that humans are deeply connected to the earth, and our survival depends on the food it brings forth.

The earth can’t produce food yet in verse 2 — it’s “formless and empty,” at least, that’s how our NIV translates these words; but the Doug Green translation, which I quite like because of how it creates threads through the rest of the story of the Bible — is that these words should be maybe understood as barren — desolate — fruitless — and uninhabited by life… Especially living creatures who’ll cultivate it (note: Doug Green, Old Testament lecturer at Queensland Theological College is a member of our congregation).

Jeremiah uses this same language to talk about Israel as the nation goes into exile; framing exile as a sort of de-creation — where the formless and empty involves the people — the birds — and the trees — all disappearing — it becomes desolate and uninhabited.

In Genesis the land is desolate and uninhabited, because it is covered in the chaotic waters of the deep, and it’s all in darkness.

In the ancient map of reality the deep — these waters — represent chaos. People who hadn’t seen the earth through a satellite conceived of reality as looking something like this.

Image Credit/Source: Michæl Paukner, Flickr

They’re maybe even a spiritual force opposed to life and fruitful living, especially salt waters. In Babylon’s creation story there are two gods who make up the deep — the living water — freshwater — Apsu — and the salty chaos waters — Tiamet — who their god Marduk violently destroys and he makes the heavens and the earth from the material of her dead body.

The deep is a problem. It gets in the way of the land becoming something other than desolate and uninhabited — it stops it teeming with life and fruitfulness.

God does something about this, and about the darkness. His spirit, a word you can also translate as breath — something that needs to be active in order to speak words (try holding your breath for a minute and then speaking) is hovering over the waters of the deep, in the darkness; waiting to bring life. God speaks to create: “let there be light”. And there is, which deals with the darkness. This happens before he creates the sun, and so there’s a cool idea that he peels back the veil — or the vault — between heaven and earth to flood the earth with his glorious light.

Then God starts dealing with the waters. He says let there be a vault — or firmament. This is what gets created on day two — separating water from water — the waters below and the water above — this isn’t how we think of the earth and the atmosphere as modern people, but sit for a bit with this vision from Genesis where the heavens and the earth exist, and they’re held separate by this solid barrier — this domed ceiling. God carves out a space between these waters for life to exist on the earth, by his word, then moves the waters aside so that dry ground — ground that can produce fruit and life — appears. He calls this good, which is interesting because on the previous day, as he creates the vault — this barrier between the heavens and the earth — he doesn’t call it good.

There are lots of reasons this could be the case, but I wonder (with others) if Genesis is setting up a tension that will be resolved in the rest of the story of the Bible. A separation between the heavens and the earth — a barrier — exists and this will ultimately be overcome. In the rest of Genesis 1, God fills the heavens, and sea, and sky with life — heavenly bodies, that for the ancients were a shining picture of the heavenly court —spiritual beings — and trees — and animals (note: I wish I’d paid more attention to this when preaching this series, but my mind has recently been blown by the Hebrew of Genesis 1:21 the ‘great creatures’ he creates in the deep; using a word often translated as monster, serpent, or dragon). It follows this pattern — God says, he makes, and he names. He fills the desolate and uninhabited world with fruitfulness and life.

He does it by speaking, and by creating not so much from out of nothing, but from his word, with his Spirit hovering. This creator god we meet in Genesis 1 is the source of all the things he makes. He’s not like the gods of the nations — whose creation stories do not involve an eternal god who creates life, but gods who are the chaotic waters (Tiamet) and at home in the darkness. The gods from origin stories around Israel bring light and order to the desolate earth by killing each other, and building stuff out of the dead bodies of other gods. That’s the kind of bloody origin story that gets you an ancient Gotham city; heroes — or kings — who embody fear, and employ violence to get what they want in empires that brings order — their own fruitful gardens and cities — through war and bloodshed.

In Genesis, God makes the pinnacle of creation; those who will rule for him on the earth as he rules in the heavens. Those who’ll represent him and bring fruitfulness over the face of the earth as we spread his rule and his presence by spreading his image — reflecting his glorious light and joining him in the generation of life and fruitfulness in the earth. He specifically gives humans the job of ruling over the spaces and the life he has just created — fruitfully, and according to his likeness.

There’s a plural here — the god who is speaking doesn’t just say ‘let me’ — and there’s a bit of debate over who the us is here — for a long time I read it as a divine plural — an intra-trinitarian ‘us’ — the Father speaking to the Son and Spirit who are at work in these acts of creation, but there’s a solid case to be made that God — the Triune god — is speaking to the heavenly realm and those living in his divine court — the heavenly ‘sons of god’ as they’re called later in the Genesis narrative — so that we’re like those heavenly beings, but on earth. Psalm 8 picks up this idea a bit. It talks about God making humans ‘a little lower than the angels’… Only, in Hebrew, it’s ”a little lower than the Elohim” — which is a tricky word — a Hebrew word for ‘god’ (a divine being) where the plural and singular are hard to tell apart. The translation decision here is an interesting one, and angels could just as easily be ‘gods’ — these other ‘Elohim’ — who turn up a bit in the Old Testament, like in Psalm 82, which describes God (Elohim) ruling in the heavenly court room — rendering judgment amongst the Elohim. In our modern view of the world we aren’t necessarily looking for heavenly beings in a heavenly court room, or imagining God talking to this court as he creates humans to do this job on earth.

This isn’t our model of reality, but it is the model the Bible assumes, and the Bible’s origin story tells the story of the creation of this same cosmos.

While i’m still inclined to see the Trinity involved in the us — in the creation of humans — I do think we humans are being made to do on earth what these Elohim — the sons of God — are meant to do in the heavenly realm; be like God; be like his children who represent his rule as we rule for him.

Being made in god’s image is tied to a function; to rule over his creation as those who bring his likeness into creation.

In our secular world, where we tend to be materialists, because of our origin stories, and so focus on physical stuff, we tend to think of making something as making its substance. So we see the idea of the “image of god: being something about our human bodies that is inherent to us, and how we operate physically, but in the ancient world, when you made and named something it wasn’t so much about material nature but about function. The image of god is a job to do, not just a thing we are.

There’s some evidence from the ancient world around Israel that clues us in to this. In the ancient near east the title the “image of god” was a title reserved for kings — who were really more priest-kings who represented their god’s rule on the earth, and guaranteed their worship — and for idol statues — that’s actually what the word here for image — tselem — means both in Hebrew and related languages from nearby countries.

So when god makes humans in his own image — in the image of god he creates us — as male and female — you could think of it as him making us as his living, breathing, idol statues — so that wherever humans doing this job are, there the rule of God; the kingdom of God — is represented on the earth, as it is in heaven.

This is an idea we’ll see more of in the next piece, but it’s also an idea that runs through the story of the Bible, especially as god forbids his people to make dead statues of him — the living God — cause he’s already made his own living images.

One of the reasons I’m still partial to the idea of the Trinity being involved in the “us” — is that I think God making us male and female in his image is significant; not just because it upholds the dignity and function and full humanity of both men and women, but because men and women — a plurality of people — are actually required to carry out the function of being made in god’s image together. There’s a communal reality in the us that we’re to represent in our own us as we take on this job together and generate fruitful life the way god does, in partnership with him.

That’s the job he gives humans — the world was uninhabited and empty — desolate and uninhabited — but now, with the creation of humans — it’s not — and we’re given a job — to fill the earth and subdue it — as we rule over the wild life we find around us; joining God in bringing light and life and his presence over the face of the earth…

At this point god declares things very good. Now, it would be easy for us to think that this is perfect; that the picture we get at the end of chapter 1 is a perfect world — a paradise that humans stuff up as sin enters the picture, but the idea that we have a job to do in subduing the world — and what we see in Eden in chapter 2 — is that not all the earth is Eden yet… It’s not all a picture of god’s heavenly dwelling…

We humans become the answer to the problem of the land being desolate — uncultivated wilderness — by bringing fruitfulness, and we’ll see more of what both image bearing and this task looks like as we explore Genesis 2.

There are other issues unresolved in Genesis 1 that mean we shouldn’t think things are perfect at this point. The cosmic waters — are being held at bay — in the ancient worldview — gathered up and pushed aside, waiting above the firmament to be poured out; as we’ll see in the Noah story. The firmament is still existing as a ‘not called good’ barrier between heaven and earth, which is a problem set up in the Genesis 1 “origin story” that is resolved in the rest the Bible as God’s big story unfolds.

So how should we understand this story in the beginning of our Bible?

For starters — it’s a story that reveals God to us because it shows us how the world — his creation — is an expression of who he is. He makes light and makes life and pushes the forces of chaos and disorder aside to replace that with fruitfulness and order, and he does this in a way that transcends anything offered by any other gods we meet in any other creation story. The rest of the bible picks up this theme. The Psalms use creation itself — its wonder — as grounds to declare the glory of God.

In the book of Acts, Paul talks about God as the one who makes the heavens and the earth — and suggests we should look for God not in human temples, because he doesn’t just create the world by his word — and spirit, or breath. Existence is in him; he gives everyone life and breath and everything else. And in him we live and breathe and have our being.

In Romans, Paul picks up the same idea and says that god’s nature — his invisible qualities — are knowable, in part, from what has been made — the works of his hands; and this actually leaves us without excuse; creation is evidence of a creator.

The goodness of the cosmos — its beauty, its vastness — the flavours of the things God gives us for food — and the nature of the life filling it — these reveal God’s qualities to us, but nothing does this more than humans.

And heaven and earth — and the barrier between heaven and us is a something God sets about removing. Ultimately he does this in Jesus — the Son of God, and Son of Man; the first person to span heaven and earth in his nature. There’s this cool thing Mark does in his gospel called an ‘inclusio’ — it’s a technique where two events are bracketed using the same words and themes. At the baptism of Jesus, the heavens tear — this is a violent rupture type word — and the Spirit of God, who hovered over the waters in the beginning like a dove now hovers over Jesus (Mark 1:10). This ‘inclusio’ is complete when the curtain in the temple is torn from the heavens — up top — to the earth — the bottom; it’s the same word (Mark 15:38).

We know from the Jewish historian Josephus that this curtain was an image not just of the universe, but of the firmament — the barrier between heaven and earth. He talks about how its colours represented the heavens, how the stars and cherubim embroidered on it represented the mystical living creatures in the heavenly realm (Josephus, Jewish Wars Book 5, Chapter 5, Paragraph 4). At the death of Jesus the vault — the firmament — breaks open. The barrier is destroyed. A new creation — a new state of being — emerges.

Paul picks up the language of Genesis to describe Jesus as the firstborn over all creation — the image of the invisible god — the child; the living idol statue; the ruler of god’s kingdom. He says that creation itself — the heavens and the earth — things visible and invisible — the Elohim and the rulers of earth — all things were created through him and for him. He’s the one who will remove the barriers between the good cosmos and the perfect one. Because God was pleased to have all his fullness dwell in him — and through him to reconcile all things — that means to bring all things together — and it includes the heavens and the earth — by making peace through his blood, shed on the cross (Colossians 1:15-23).

Paul talks about how we’ve been raised with Christ, and we’re now seated in the heavenlies — but this isn’t meant to make us of no use on earth — when we set our minds on things above it’s on God and his nature as it’s revealed in Jesus (Colossians 3:1-3). It’s on this story where the heavens and the earth are not yet joined and we live in anticipation of his return to make all things new. This is the cosmic good news where Jesus doesn’t just come to reconcile us to god by forgiving our sins — he does that — but to recreate all things. That’s where the big story of the Bible heads. The beginning anticipates the ending: a new heaven and a new earth, where, finally, there’s no cosmic waters (I don’t think this means no beach but no chaotic abyss) (Revelation 21-22).

In this new reality God will dwell with his people; there’ll be no solid barrier between us. No curtain. No separation of realms. This is the end of the story, and the threads begin in the beginning.

The Bible’s origin story shapes how we understand the world — where it came from — and where it’s heading — not in the way science tells us the world works, and not in the way other religious stories — whether supernatural or built from worshiping created things instead of the creator — tell us the world should work. And this should actually shape the way we live in the world — in our part of it.

This was a big deal for Israel; this origin story was the beginning of the story that explained how they should live as image bearers; as a kingdom of priests, not just in the land, with a king in Jerusalem — but in Babylon; in exile, when it felt like decreation had happened and as though the powerful origin story of Babylon — that justified its military power and propped up the regime of its kings — was the better story. The Bible’s story taught Israel to imagine a different humanity; a different purpose as it told the story of a different God.

So let’s, for a moment, re-imagine our world if the Bible’s origin story is our origin story — not just in the beginning, but in the story of re-creation we find in the Gospel; the end of humanity’s exile from God. Let’s imagine we’re reading this story in Babylon; or in Gotham — the world we live in can be pretty dark.

Let’s imagine how our new origin story — the Gospel Story that starts in Genesis — should shape the way we live in our time and place; because it’s different to the stories at work around us…

If you buy an origin story that is all about the material reality, or ‘this is all just chance,’ and ‘nature is red in tooth and claw and we’re just the top of the food chain then you want to be a predator, not prey. You want to be the fittest in order to survive and others become obstacles. This is the world we live in. Often. A world of dominance hierarchies and military industrial complexes and consumerism and climate change induced by our ‘dominance’ of the physical world. You start treating the world as though it, too, is prey — and so we dig things up and pump stuff out, and burn stuff up, and destroy natural habitats and food sources and the water basins. And we leave the land desolate and uninhabitable when we finish. Perhaps, over time, instead of spreading God’s Kingdom — Eden like life — we change the climate and push back towards a formless and empty creation, with only God’s gracious sustaining of life holding back the waters of judgment. It’s possible, too, that what restrains us from fully destroying the joint is that the image of god is still at work in our humanity.

You also lose a certain amount of wonder or enchantment — the idea that we live and have our being ‘in God,’ and that his divine nature and character is revealed in what has been made. Instead of cultivating a fruitful relationship with the world reflecting the God who makes the world fruitful and inhabited.

Sometimes we’re tempted to live in this story. The Babylon story. The story from our family of origin where we make progress through death and destruction bearing the image of beastly gods of death, but God invites us into a new family tree, with a new story.

Our story teaches us that the right use of the world lines up with the purpose of human life — to reveal the nature of god in his world as we rule our lives, and the world, under his rule as expressions of his kingdom; of heaven breaking in to earth. Our story is about God’s design and gift of life, for all people, and his desire to dwell with us in a fruitful world that is full of life…

Our story shapes us to see not just ourselves — but our neighbours — as created to reflect the glory of God; so that we treat human lives — and bodies — as sacred objects, and see those people not reflecting the glory of God not as humans to be destroyed — or captured, enslaved, and bent to our will as we pursue our own heaven on earth projects — but to be invited into relationship with their creator.

Our story teaches us that God’s world is good — but it is not perfect — it isn’t something — or full of somethings — or someones — we should worship.

Our story teaches us that God provides the answer to the longings created by life in a good world that points us to a great God, working out a great story in history — the story of heaven and earth coming together… And that right now, we’re between those two worlds.

Our story is that in Jesus we become meeting places between heaven and earth — restored and re-created image bearers who become children of God who live as living statues, temples of his Spirit, who represent him — his divine nature and character — in the world. This story begins in the beginning.

Comments

[…] in Genesis chapter 1, we’re told God creates people in his own image, and I said that word is the word that gets used for idol statues and for kings in the ancient world. There’s a fascinating thing going on here where this story of God creating a living image of […]

[…] In the Beginning (Genesis 1): An introduction to the idea of the heavens and the earth being separate realms created in the beginning, to ancient cosmology, and to the idea that the Genesis story is both literature read through Israel’s history — especially in exile in Babylon, and that it creates themes threaded through the entire narrative of the Bible, fulfilled in Jesus. Genesis 1 presents heaven and earth being separate as a reality that will create tension through the narrative, and the primordial state of being ’empty and uninhabited’ as something God’s representative image bearing humans will join him in overcoming as we fill it not just with the life he creates, but with his rule and presence. […]