This is an amended (and extended) version of a sermon I preached at City South Presbyterian Church in 2022. If you’d prefer to listen to this (spotify link), or watch it on a video, you can do that. It runs for 35 minutes.

Of all the questions i’m planning to ask God when i get to see him face to face it’s who are the Nephilim? No passage has been a pebble in my shoe like this one, but I wonder if I’m alone. How many of us have just got to this bit and filed it in the ‘too weird’ basket?

That’s fair. Maybe. But it could also be that like so many of the chapters we’ve looked at so far in the Bible’s origin story that this one has incredible pay off with a bunch of threads that run from here through to the end of the story. So let’s dig into it a bit and see what we find.

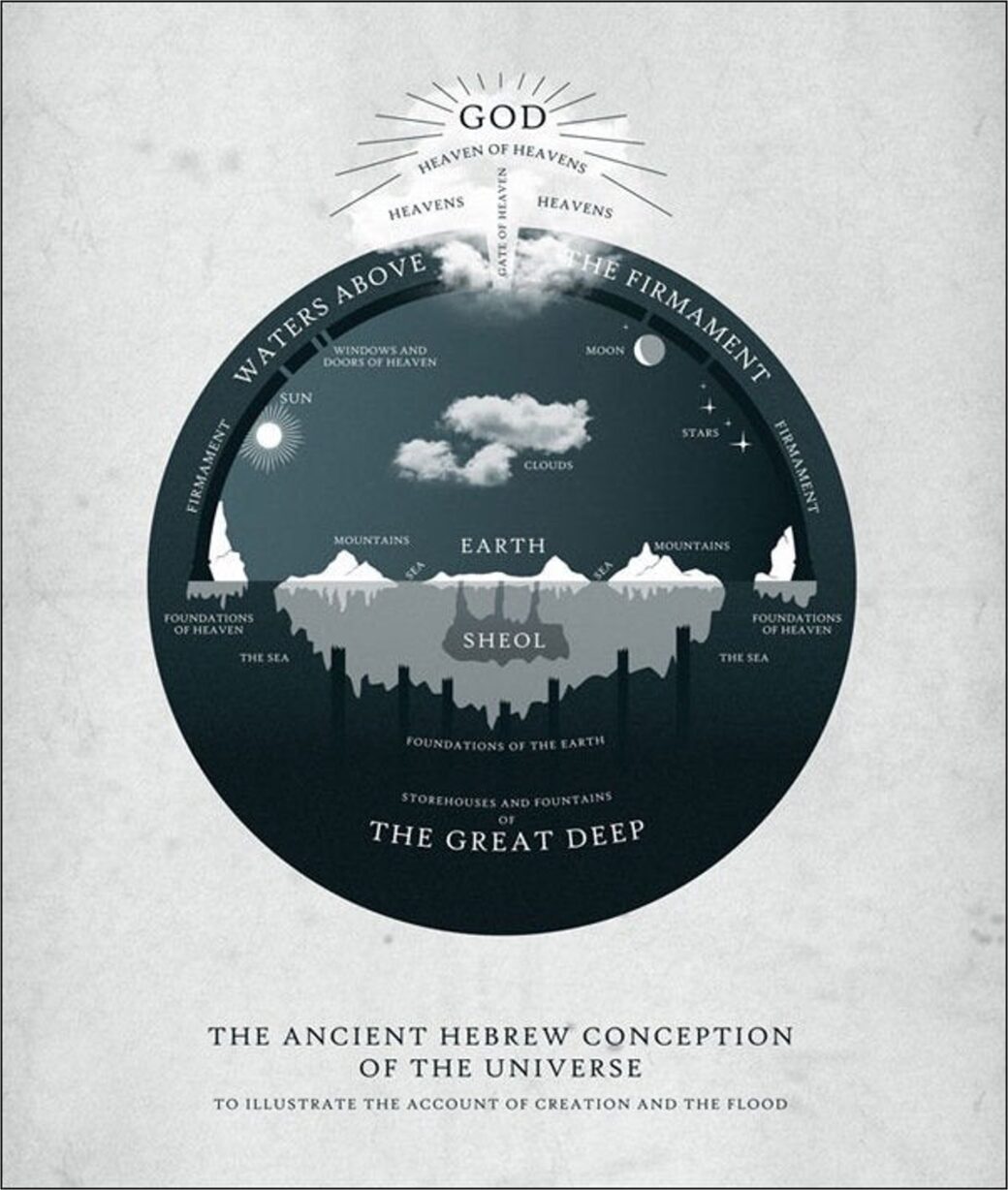

This is a passage that at this point in the story creates more questions than it answers. Like does this mean the ancient model of reality is right, with supernatural beings dwelling in the heavens above? Who are the “sons of God” (Genesis 6:2)? What are the Nephilim (Genesis 6:4)? Are they children of the sons of God, or are they the sons of God? How does this story relate to other ancient stories about half god heroes who found cities? There are stories like the Gilgamesh Epic that map onto this chunk of Genesis in interesting ways. How should we make sense of this in a modern world where most of us don’t really believe in angels or demons that interact with the world the way we see it happen here? Can something so confusing be important at all? Those are just some of my questions. Maybe you’ve got others.

I’m going to sketch out some building blocks for us as we answer some of these questions, and then we’ll look at some of the different constructions people have put together with those blocks, and I’ll unpack how I think this all works, but this is a more tentative and speculative sermon than normal.

Maybe before we begin it would be worth trying to put ourselves in the headspace of this story. I wonder, for those of us who are Christians, do you think without the Gospel’s promise of eternal life, that eternal life is something you would be searching for? If you’re here today and not a Christian, is immortality something you think about? Because in some ways, if not for the Gospel, that feels like a thing that belongs in fairy stories. This quest was a massive part of ancient epic stories — like the Gilgamesh Epic, which tells the story of a demigod hero chasing eternal life, and a serpent who took it away. It’s at the heart of the legendary quest to find the Holy Grail; the cup that was meant to give eternal life, or the Philosopher’s Stone in Harry Potter, used to produce the Elixir of Life.

And maybe we don’t live by fairy tales, but we do still quest after Holy Grails. There are people who want science to figure out how to undo aging and death, or technology to offer a solution where we can digitise our consciousness. Others of us just want a legacy; a name that will mean something after our death, or families who will benefit from our heroic triumph over the odds. Whether or not the hunt for heavenly life drives our neighbours now, or is just something we take for granted, it’s a big part of Genesis after the loss of the Tree of Life.

This is another story about what was lost in humanity’s exile from Eden; just note how this passage is bookended with Noah (Genesis 5:30-31, 6:8). A big chunk of the next few chapters of Genesis deal with Noah’s epic journey — a story of de-creation and re-creation.

We’re told at the end of the family tree from Seth to Noah in Genesis 5 that “he will comfort us in the labour and painful toil of our hands caused by the ground the lord has cursed” (Genesis 5:29). He’s presented as a bit of a curse reverser, but then things take an odd turn. Humans are being fruitful and multiplying; increasing in number, and they’re having daughters (Genesis 6:1), and then these sons of God, there’s an interesting parallel in the Hebrew wording here, they repeat the pattern of Eve in the garden with the forbidden fruit, they “see” that the women are beautiful (the Hebrew word “tov”), and they “take” them as wives (the word “laqach”). It’s the fall again. The parallel is meant to draw our attention to that. Something here is not good.

So who are these “sons of God,” there are a few different options for how this passage has been read. One line of thinking is that this is about the line of Seth; the good human line of seed, mixing with the line of Cain — the line of the serpent, so that there’s no pure line anymore. This’d mean reading the throughline from Adam being made in the image of God and Seth being made in the image of Adam, to see this as a line of sons of God (Genesis 5:1-3), so the repeat of the fall means the whole line gets corrupted. It makes a bit of sense, sure, especially if you don’t want a supernatural reading here. But, remember, one of the things we’re doing here is looking at how this story launches threads — connections — that run through the rest of the story of the Bible, all the way to Jesus, and then on into the new creation.

The modern way of reading the text runs into some problems when we see how this phrase “sons of God” is used through the Old Testament to refer to spiritual beings. Which means my inclination is to take a second view. In this other line of thinking there’s a series of threads that run from here to build that two-tiered picture of reality we saw back in Genesis 1, where god creates “the heavens” and “the earth,” and creates humans — on earth — to be in his image, but also to be like the heavenly beings. We saw how places like Psalm 8 mirror the roles of angels in the heavens and humans on earth; and how sometimes these angels are described as Elohim — the Hebrew word for gods — and even sometimes as sons of God (Psalm 8:4-5). You’ll find an example of this in Job 1, where the sons of God — and Satan — turn up in the heavenly court room (Job 1:6), and in Psalm 82, where Elohim — god most high — rules amongst the Elohim — the gods (Psalm 82:1, 6-7). Elohim is a tricky Hebrew word that is both singular and plural and so you’ve got to figure out what’s going on based on the context.

These Elohim, in the Psalm, are called sons of God, and it even describes how some of these sons of God will fall like other rulers — that they’ll become mortal. And there’s one more really interesting reference to the “sons of God” in Deuteronomy 32 — this one’s a bit trickier because the oldest manuscripts of the Old Testament we have use ‘sons of God,’ but a more recent full Hebrew text of the Old Testament that our translations typically follow has “sons of Israel” — but just note what it says here in Deuteronomy 32; the nations that aren’t Israel are given to these sons of God, while God keeps Israel as his special people (Deuteronomy 32:8-9). This alternative reading of Deuteronomy 32 begins in Genesis 6.

So before we get to the next bit, the Nephilim, lets recap what we see here. It’s a repeat of the pattern of the fall, but it’s the fall of spiritual beings, “spiritual sons of God,” this is a description of a heavenly fall; a rebellion against god in the heavens. Created beings seeking to marry heaven and earth — bring them together — without God in the mix; perhaps immortal spiritual beings looking to pass on their immortality, their heavenly life, to a bunch of beautiful humans exiled from the Garden, and maybe some humans who are happy to get that immortality any way they can. Which explains the seemingly random segue from these marriages to God limiting the lifespan of the human to 120 years (Genesis 6:3). Humans are mortal; this sort of marriage between heaven and earth is not going to be a path to immortality.

And this leads into the weird stuff about the Nephilim. We’re not told directly that they’re divine-human offspring; just that they appear when the sons of God marry the daughters of humans, but it’s very much implied. Though they could also be the sons of God, now stuck on earth — the name, or word, ‘Nephilim’ seems to be derived from the “fallen ones.” We get this thing where these fallen ones are on the earth in those days, and later — when the sons of God have children with the daughters of man, and we can infer these Nephilim are the offspring produced by this union; then we’re told they’re the heroes of old; and literally “men of a name” (Genesis 6:4).

There’s an interesting parallel between this story and one coming up, the tower of Babel. In this story heavenly beings try to marry heaven and earth by coming down, and we end up with people of a name, while in the Babel story humans try to “make a name for themselves” by bringing earth to the heavens on their own terms.

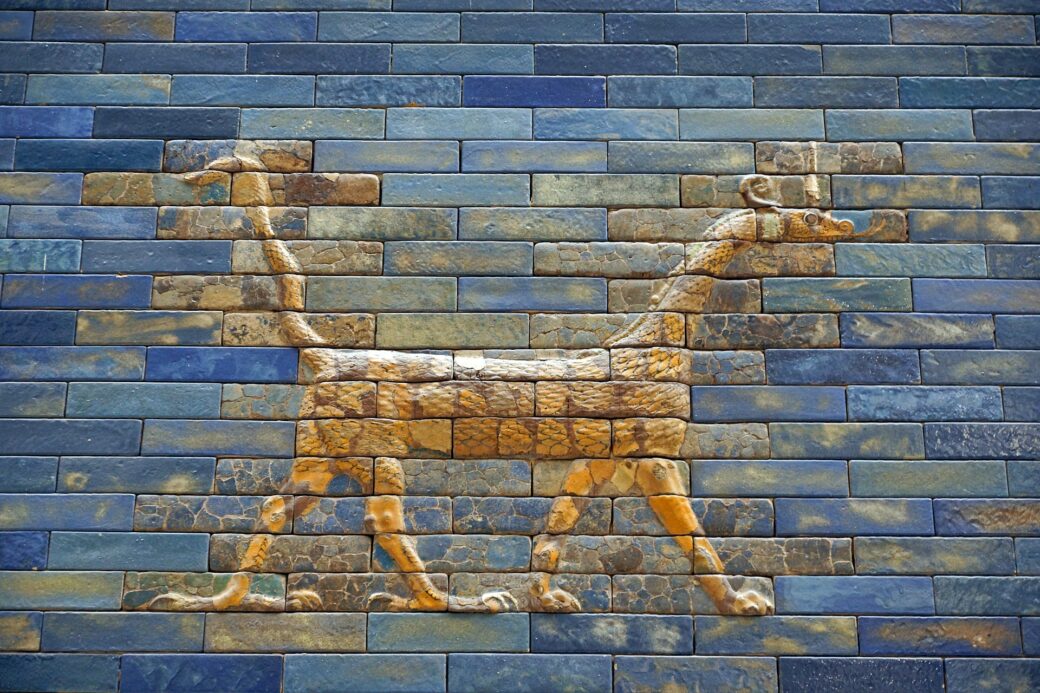

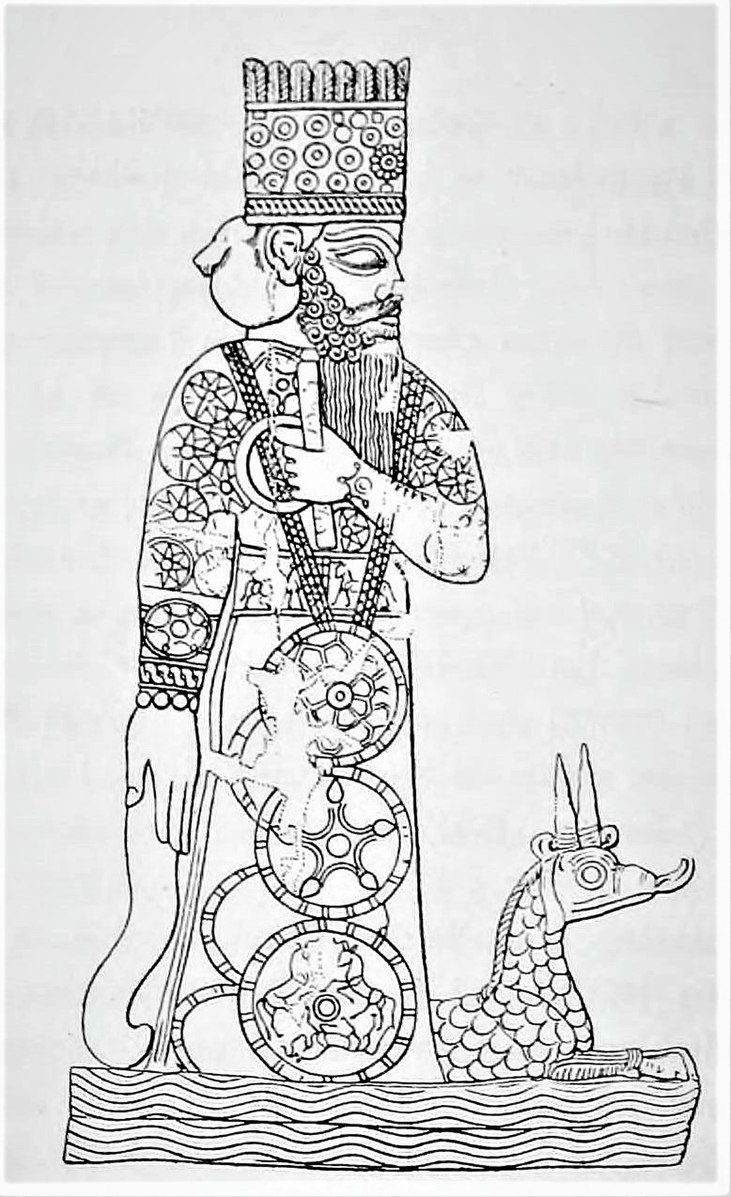

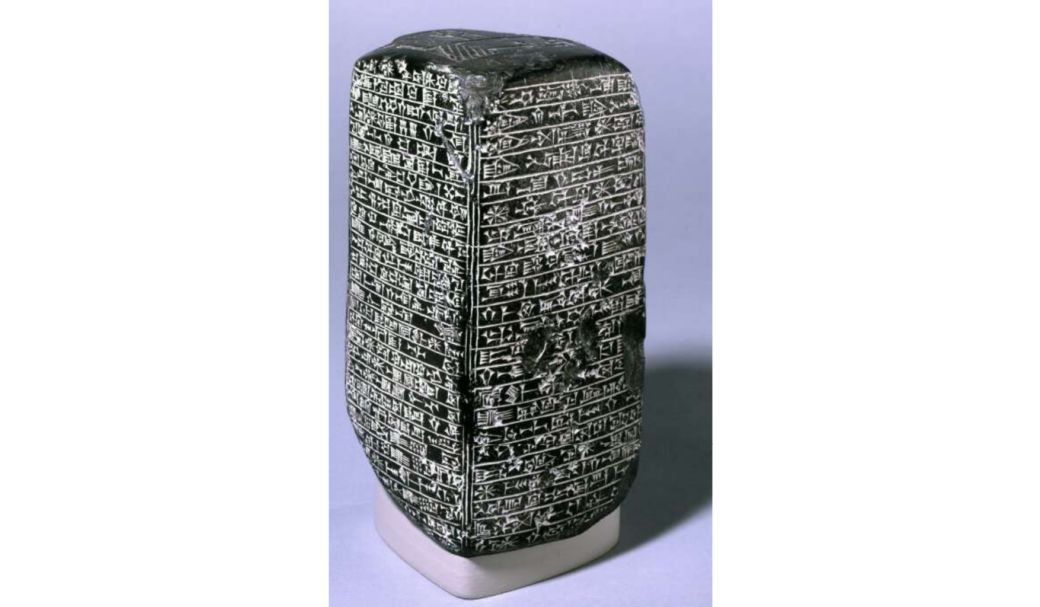

In all this there’s also a bunch of parallels to what people in the ancient world believed about Gods and kings and heroic demi-gods and the world, stories we can read today, like Gilgamesh, or the Enuma Elish, where divine-human heroes establish powerful kingdoms of the world — like Babylon — in league with cosmic beings. In these stories these heaven-and-earth unions are a good thing. In the Bible, the heroes held up by these other nations are a picture of cosmic rebellion against god. This could explain, too, why so many cultures have pantheons of gods — demigods — and mythical heroes.

There’s a thing that emerges in the storyline of the Bible from here on that views these characters as giants; mighty warriors . What’s interesting is that these giants all appear after the flood that is about to wipe all life that isn’t on the ark from the face of the earth. That’s a conundrum, like who Cain is afraid of, that is created by a straightforward reading of the biblical text and even the same chunk of the text; the books collected together as the writings of Moses. Because we meet some descendants of the Nephilim as the story unfolds. It could be that Nephilim emerge whenever sons of God marry human women, so this pattern continues; or that the flood isn’t global, but is a significant story of de-creation and re-creation of a family of God’s people who’ll relaunch the human project (it could also be that the story is operating as a polemic against the view of the world held by the Babylonians enslaving Israel in the exile).

Here’s a few times giant descendants of the Nephilim turn up, with a few different Hebrew names, and we can do a little bit of detective work here, that’ll hopefully pay off. In Genesis 14 we meet a group called the rephaites, a Hebrew word for giant (Genesis 14:5). In Numbers 13 the spies come back from Canaan saying the people who live there are Nephilim – Anakites — giants (Numbers 13:32-33). In Deuteronomy 2 we get a recap of the giant people — the Emites, the Anakites — Nephilim descendants — who are Rephaim, who get called Emites by the Moabites (Deuteronomy 2:10-11).You following? The point is that giants, whatever they’re called, are the baddies – connected back to the Nephilim story. There’s another story about Og, the king of the Rephaites who’s so big his bed becomes a tourist attraction (Deuteronomy 3:11). This human opposition — from nations given to the ‘sons of God’ in Deuteronomy, is connected to a story of cosmic rebellion, and their giant offspring. These giant people — mighty warriors — crop up as those opposed to God’s people and to the fulfilment of his promises; like those opposed to God’s people as they seek to settle in the new Eden; the promised land. These divine-human-giants are enemies of God; fallen spiritual beings who join the serpent in his beastly opposition to god’s plans for fruitfulness. And this type of bad guy gets introduced back here in Genesis 6. Are you with me so far?

Cause here’s where it gets fun. Maybe. Israel’s story is a story of giant killing saviours; and each time we ask ‘will this hero and his mighty warriors’ be the serpent crusher as well. The first is Joshua. As Joshua enters the promised land he leads a campaign of giant killing. In Joshua 11 we’re told he “destroys all the Anakites” from the lands of Judah and Israel (Joshua 11:21). He’s the leader who leads god’s people into the promised land and makes it giant free. These giants opposed to god are left out there in Gaza, Gath, and Ashdod (Joshua 11:22). Gentile territory. The land of the Philistines.

The land of goliath, the giant (1 Samuel 17:4). Goliath is a giant who is pictured as a serpent; a scaly bronze enemy of god’s people. Every time “bronze” is mentioned in the description of Goliath’s scaly armour it’s a play on the word for Serpent. This is the Hebrew word for serpent in Hebrew above the Hebrew word for bronze. You read them right to left, these first three consonants are the same (Hebrew wasn’t written with vowels, they get added later.) It’s like written pun.

Bronze and scaley; these are snakey words.

Goliath is a giant serpent who ends up belly on the ground with his head crushed by god’s anointed king, like a child of the serpent meeting the seed of god’s family (remember the curse where the serpent would ‘crawl on its belly,’ eat dust, and have his head on the ground (Genesis 3:14, 1 Samuel 17:46, 49).

David’s mighty men are later described as killers of Rephaim — descendants of Rapha — first Ishbi-benob (2 Samuel 21:16-17), then Saph (2 Samuel 21:18), then the brother of Goliath (2 Samuel 21:19), then a giant with six fingers and toes on each hand — also from Gath — also a descendant of Rapha (2 Samuel 21:20), these relatives of Goliath are all called descendants of Rapha; Rephaim; descendants of the Nephilim; allies of the serpent; the fruit of rebellion against God in the heavenly realm being dealt with by a giant-killing annointed leader of god’s people.

David is the king of the giant killers — but he’s not the deliverer, because he ends up acting like the fallen ones. David has his own band of mighty warriors; heroes of old; it’s the same Hebrew word from Genesis 6. And this list of 37 mighty warriors ends with one name that zeroes in on David’s failure — Uriah the Hittite (husband of Bathsheba) (2 Samuel 23:39); where the way he operated that invites a comparison with the fallen ones; the cosmic rebels.

In David’s ‘fall,’ as he takes and rapes Bathsheba, the narrative parallels not just with the fall (Genesis 3), but with the fall of the sons of God, with those same three Hebrew words; he sees that Bathsheba is beautiful (tov), and sends his men to take her (laqach) (2 Samuel 11:2-4). The narrator is showing us that despite crushing serpent-Goliath, David is not the king who’ll crush the serpent, and lead people back to immortality and heaven-on-earth life with God, even if he and his men are giant killers. He ends up in the serpent’s coils too. He ends up like one of the sons of God ‘taking’ and marrying a human wife; like a king of the nations, and, ultimately, Israel ends up in the land of mighty demigods, Babylon, a land given to the sons of God, and to “men of name,” to be ruled in violent rebellion to God, because David’s sons follow his pattern, only worse.

The Genesis story makes the issue causing exile — God’s judgment — a de-creation where people are removed from the fruitful ground, an issue of the human heart (Genesis 6:5-7); it’s not the cosmic rebellion that leads to the wipeout, but the wickedness of god’s earthly representatives.

Just as the sin of the humans in the days of the Nephilim led to exile, to decreation — through the flood — so the repeating of this pattern leads to exile from God; the de-creation of Israel’s fruitful land and their place as god’s fruitful people in the world. If you’re sitting in Babylon looking at the mighty warrior kings, and their companion serpents, and reading about how they’re the fruit of cosmic rebellion that leads to judgment, and you’re remembering the promise of a serpent crusher, that might stop you bending the knee to the mighty kings of Babylon.

We’ll dig into the flood story next week; but there are two ways this pre-amble sets the scene; what’s about to happen is de-creation; judgment that will deal with the rebellion of the sons of god, but that is particularly focused on the humans and the stuff we were meant to rule; we were not made to be ruled by the beasts, or by these sons of God, or their mighty giant warriors.

But let’s recap for a minute — this story in Genesis starts a thread that runs through the story of the bible where cosmic rebellion — spiritual sons of God — line themselves up with the behaviour the serpent leads humans towards; and humans are brought under the rule of these serpent-like sons of god, and these mighty warrior king figures who’re somehow expressions of this rebellious kingdom but on the earth.

Then even the best king of Israel — God’s chosen king — acts just like these warrior kings and cosmic rebels, even while fighting against them as God’s anointed king. The story just unapologetically has this spiritual realm existing in parallel and then intersecting rebellion against God’s rule in the heavens and the earth. Human wickedness — and our hearts — are part of the barrier to the re-ordering of the earth.

We’re waiting for a giant-killing, serpent-crushing, anointed king who won’t repeat the fall, but who’ll marry the heavens and the earth on god’s terms, and lead people back to life with God. Whether that’s Israel, who were carted off into the nations, or the nations themselves, who were ultimately given to these powers and principalities. There are some bits of the New Testament that pick up these threads around the Nephilim — Peter in 2 Peter, and the book of Jude — but there are a couple of places that tie it all together for us so that the Gospel is the fulfilment of this story.

But wait. Jesus doesn’t kill any giants. Right? He does win a victory over the rebellious sons of God, and he is described as killing a dragon to marry a bride and lead his bride into immortal heavenly life with God. What the sons of God did as an act of rebellion that led to grasping and destruction, Jesus, the son of God, does as an act of self-giving love that leads to life, and restored hearts, so that God’s spirit will dwell in humans forever.

Ephesians tells the story of the Gospel as the story of God giving humans new hearts, by the spirit. Freeing all humans — descendants of Israel, and the nations — from the clutches of the ruler of the prince of the air (Ephesians 1:13, 2:1-2), and raising us into the heavenly realms (Ephesians 2:6). So that the victory of Jesus secured through his death and resurrection and the redemption of Jews and Gentiles from captivity into one people is a reflection of a re-ordering of the heavenly realm; Jesus creating a people who are seated in the heavenly realms to reign with him is a victory over the powers and principalities and the leader of the heavenly rebellion against God’s rule (Ephesians 3:10-11). Ephesians also talks about this victory as a an act of sacrificial life-giving love that makes us holy — like God — again; a marriage between a heavenly son of God and his bride, the church (Ephesians 5:25-26, 31-32). These humans are given heavenly life; this son of God does not “take” the way the Nephilim, or David “take,” grasping; abusing; conquering, he gives himself up for his bride. He comes down from heaven, sent by the father, to bring a people into his heavenly presence.

That’s cool, and it’s the story we also see in Revelation. Revelation is just more explicit that this involves the destruction of the serpent — the leader of the cosmic rebellion, “that ancient serpent,” Satan, who leads the world astray, and his beastly human regimes (Revelation 12:9). The king that the Old Testament has us waiting for arrives to destroy the cosmic rebellion, hurling the Serpent and his minions from the spiritual world with him, tossing him into a lake of fire with his host of Spiritual rebels (Revelation 20:9-10).

And this son of God, Jesus, is the one who marries heaven and earth — on God’s terms, not human terms; creating a heaven-on-earth people to live in a heaven-on-earth city. So the story ends with the Holy city, the new Jerusalem; the new city of god’s people, descending like a bride, so that people might be united with heavenly life, in order to dwell in a new Eden (Revelation 21:2). Where we have access to eternal life from God again, the waters of life, and the tree of the life; life with God in his city (Revelation 21:6-7, 22:14). Now. I don’t know about you, but I think that’s cool.

But what’s the pay-off for us? I wonder if there’s a few ways this might shape us — first, if you’re not a follower of Jesus, there’s a confronting thing in all this that says you’re actually following other dark and unseen forces that are leading you to death as they shape our world. That’s creepy and supernatural, but a long look at the atrocities happening in Ukraine, or the mass shootings in the U.S, (or, at the time of posting, the situation in Gaza) right now makes it easier to believe there’s some beastly animating force driving humanity. Maybe there is something to this story that’s worth exploring.

And if you’re someone who is a Christian; someone who has put your trust in Jesus as the serpent-killing king, then we’re already the bride of a heavenly son of God, that he has united us with God’s life, so that we can live in this world as God’s children as people with new hearts. It’s this story, and this reality, that is meant to shape us, not other stories we might believe about ourselves or the world.

That feels pretty motherhood and apple pie on one level, but in Ephesians, Paul is pretty keen to apply this new story to our everyday relationships — church family and our households — whether we’re married or not, parents or not — and to cash it out in a call for us to live and love like Jesus in our relationships; not like the sons of God, or like David, or like Adam and Eve who go into relationships for what they can get to fulfill their own desires. So our communities look different to those ruled by dark forces.

When it comes to the ground level, it can make a little bit of difference to what feels mundane — even how we handle temptation and the pursuit of godliness — to see our decisions; our lives; as caught between these two cosmic kingdoms that form different lives on earth and lead to different eternal outcomes when Jesus returns. When we choose sin; disobedience; giving in to temptation to take or grasp the things we want — to chase immortality — to ‘marry heavenly life’ — apart from God — to embrace wickedness from our hearts — we’re caught up in the serpent’s rebellion against God in the heavens, but when we choose to live with Jesus as king, we’re aligning ourselves with God’s story as the rescued, beloved, and faithful bride; those seated in heaven, in order to bring heavenly life to earth.

We might not be chasing Holy Grails — or even thinking about eternity; but just thinking about this world and trying to build heaven here, as though this is all there is, is every bit the denial of god’s rule that we see in Genesis. Our pursuit of life without God will come to nothing, to find life not in the mythical Holy Grail, but in the cup Jesus offers is to find what those in all those ancient super-charged epic stories were looking for.