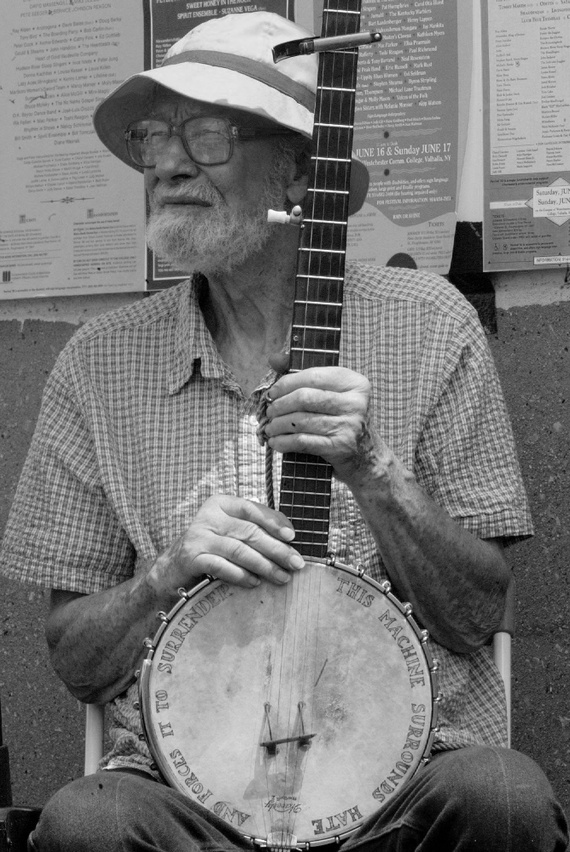

“This particular challenge is unique because at the heart of it is a universal lie, that is that all people who experience same sex attraction were born that way. And so, scientists, politicians, lobby groups, right down to the person who you sit next to on the bus who says oh, I’m same sex attracted and I was born this way, everybody seems to believe the lie. And what they do, it’s not just the lie, they take the lie and they turn it into a moral imperative that is that it’s not right to tell anybody not to live that way, the way they were born to live.” — Steve Morrison, Promo Video, Born This Way

UPDATE: Steve asked for this part of the promo to be deleted, and Matthias Media has edited the video.

UPDATE 6 Sept 2017: Steve asked for his response at the end of the post to be edited to what is there now; I’ve added a brief response to his edits.

Born This Way is a new book written by Steve Morrison, and published by Matthias Media. It attempts to help Christians grapple with one of the most pressing questions facing the Australian church: how to approach the issue of homosexuality. It asks how Christians should understand what science and the Bible have to say about same sex attraction.

Born This Way is a new book written by Steve Morrison, and published by Matthias Media. It attempts to help Christians grapple with one of the most pressing questions facing the Australian church: how to approach the issue of homosexuality. It asks how Christians should understand what science and the Bible have to say about same sex attraction.

A significant percentage of the book is good, and true. But it is fatally flawed.

How we talk about homosexuality and same sex attraction is a big deal. How we talk about sexuality for Christians and to those in the outside world is a big deal.

It’s not just a big deal in the public square — where the idea that someone would not pursue happiness and wholeness according to their natural sexual desires because of their religious belief is anathema.

It’s a big deal for real people trying to figure out how to reconcile their faith in Jesus and belief that the Gospel is identity-shaping good news, with their same sex attraction.

It’s a big deal for me personally because it’s a live issue in my family. My brother in law Mitch, my sister’s husband, is same sex attracted. He’s also in full time ministry, and involved in ministry to same sex attracted people with Liberty Inc. You can read some of his story here (see question ‘what does the bible say about homosexuality?).

I love Mitch, I love my sister, I love their kids. There are other same sex attracted brothers and sisters in Christ that I love too, but none quite so close to home as my family. It matters how people talk about this stuff because it impacts real people. I posted some tips for talking about homosexuality as Christians a while back that came from a seminar I gave at a Liberty Inc event. How people talk about this issue directly impacts people I love, so you’ll have to excuse me if it seems I’ve taken anything in this review personally, because it is personal.

I’ve invited Mitch to co-write this review. These are our words. Where we need to, we’ve distinguished between Mitch’s response, and my response.

About this Review

We’re keen to be as charitable as we possibly can as readers. We didn’t want this book to fail. We need more resources to guide thoughtful discussions on this topic, and there are thoughtful parts of this book that would be useful if they weren’t surrounded by significant problems. We’re thankful that the author, Steve Morrison, wants to encourage the church to love and reach out to homosexual people, and while there is much in this book that we believe is right and true, there are problems with this book that mean it is not a resource we can recommend, and it is not a book we can simply ignore.

Neither of us know the author personally (Nathan: I became Facebook friends with Steve in order to share this review before posting it). We are sure the book is well intentioned, and that both Matthias Media, as the publisher, and Steve Morrison, the author, had every intention to handle this topic with sensitivity, we simply think the intentions were misguided.

Steve is a human. A person. And this book represents a labour of love from him, for his readers, for the church, and for the same sex attracted people who might read the book, or be engaged in conversation by people who’ve read this book. We understand that Born This Way is well intentioned, and while we’ve responded with fairly robust criticism we’ve tried to, wherever possible, make it clear that this is a result of our response to the book and its arguments, not to Steve and his intentions.

This is a topic that is almost impossible to approach without bias if you’re directly affected, or affected via someone you love being directly affected. That’s why we’ve acknowledged our own bias up front. Sometimes this approach means we rely on assumptions that we’ve drawn as readers of the book, there are no doubt times when we’ve missed nuances in Steve’s argument or misrepresent it, but we are responding as readers who have tried to read the book carefully, these misunderstandings are, of course, something we have to take some responsibility for as readers. Sometimes our tone below might seem harsh, at times this will be a result of our own sinfulness. We’d suggest there are not many people who will approach this book with the objectivity that Steve tries to write with, and assumes from his readers, and that is actually a problem with this book as it speaks to this topic.

We’ve been urged by the publisher to review the book on its own terms, not our own. And that’s fair and gracious, so in order to do this we’ve included relatively long quotes from the book when we quote it, to provide appropriate context. In Steve’s response to an earlier form of the review (published at the bottom) he mentioned that relying on quotes from the video (featuring him) produced by the publisher to promote the book, rather than the book, would potentially misrepresent the book. We feel this represents something of the shifting landscape of book publishing in the digital world. It’s probable that more people will end up seeing the promo video than watching the book, and books are (as they always have been) part of a broader conversation on a topic, promotional videos for books also contribute to this broader conversation.

We write as people for whom this issue matters, for the reasons outlined above, and because we both want to see people — heterosexual or homosexual — come to find their satisfaction and identity in Jesus. We have no doubt that this is the hope and prayer of Matthias Media and Steve Morrison, however, we have grave concerns based on our own impressions of the book and its arguments that it will be helpful to this end.

There are things to like about this book.

Born This Way doesn’t sweep the science that suggests there might be a biological component of same sex attraction out of the way, it isn’t embarrassed by the science. This is good. It asks honest and searching questions of the science, and it turns to the Bible for answers confident that the science and the Bible will walk in lock-step on the issue. This is good too. It reads the Biblical data through a Gospel lens, which is vital.

And, it invites readers to approach the topic of same sex attraction, and those who are same sex attracted, with humility.

“Let’s love and accept each other as fellow human beings. We are all different, and we all have much to learn from one another. If we can do that, we can move beyond the idea that simply holding a different opinion means someone is irrational, crazy, and driven by fear. Instead, we can relate to each other with love and respect despite our differences. We can talk, and we can listen. And we may just be able to move forward in the search for truth.” — Page 28

Which is excellent.

But.

Here are the ten reasons Born This Way is dramatically flawed, and we do not believe it’s a book you should give to those who are thinking about same sex attraction and Christianity, especially not people who are same sex attracted.

1. Born This Way presents the Gospel in its treatment of the Bible, but is not Gospel driven

The Gospel is part of the picture in this book, but we’re convinced the Gospel is the driving force behind any true answer to how Christians think about Homosexuality. This objection has nothing to do with the order of Morrison’s argument — that he starts by considering the science — but rather the conclusions he draws from the scientific and Biblical data. His conclusions are essentially that the science suggests most people can choose not to be same sex attracted, and that every person can choose fight same sex temptation, and avoid lust or same sex sex, while the Bible tells people that lust and sex outside of marriage are sinful so people must find forgiveness for sexual sin in Jesus and then stop sinning. The emphasis is very much on sin, and forgiveness, both of which are important. But the Gospel isn’t just the rationale for transformation, it’s the key, and it’s the reason to pursue sexual transformation rather than the satisfaction of natural desires.

It’s the Gospel that makes every one of us — heterosexual or homosexual — sexually whole.

It’s only when our hearts, and relationships, are transformed by the Gospel, and by our participation in the Kingdom of God through Jesus by his death, resurrection and the provision of the Holy Spirit that any of us can think rightly about our sexuality and our identity.

It’s only the renewed mind and transformed heart that the Gospel brings that anyone can begin to sort out how much our identity is formed by what’s natural to us, and how much it comes from above.

It’s this new mind, not understanding the science, that will convince someone to submit their sexuality to Jesus. Born This Way seems to assume that just understanding the science and the Bible will change actions. But it’s Jesus.

Finding sexual wholeness is about turning to Jesus, not simply turning away from sin. It is quite probably that Morrison feels like this is the message his book conveys, and that we are misrepresenting him at this point, but his emphasis is on turning away from sin and finding forgiveness (while trying to sin no more), rather than finding satisfaction in Jesus, and living accordingly.

2. Born This Way presents an anemic Gospel

Born This Way makes the Gospel about having our sins — especially sexual sins — forgiven. Which of course is part of the Gospel. But it’s not the whole Gospel. It’s not all the Gospel has to say about sexuality.

The Gospel is about the Lordship of Jesus over every facet of our lives. Including our sexuality.

It’s about being part of God’s Kingdom.

It’s about the promise that the reinvention of our humanity as we’re reconnected with God and transformed into the image of Christ, in a community of people who want to love each other like Jesus loved, with the promise of a share in his inheritance for eternity, is better than anything this world has to offer. Including sex with people you’re attracted to if those people are not the person you are married to. Including sex with people the same gender as you, even if you’re attracted to them.

Being part of the Kingdom of God, as a result of the Gospel, changes our approach to sex. The Gospel isn’t just about having your sexual sins forgiven, it’s a promise that Jesus and his Kingdom is more satisfying than sex, and a better place to build your identity and understand what it means to be human than sexuality.

This is why Jesus says:

“For there are eunuchs who were born that way, and there are eunuchs who have been made eunuchs by others—and there are those who choose to live like eunuchs for the sake of the kingdom of heaven. The one who can accept this should accept it.” — Matthew 19:12

This passage was curiously absent from the book.

It’s why Paul says:

Now to the unmarried and the widows I say: It is good for them to stay unmarried, as I do. But if they cannot control themselves, they should marry, for it is better to marry than to burn with passion. —1 Corinthians 7:8-9

Figuring out how to deal with homosexuality, especially for the same sex attracted, is not a question of science (though the science shows us the state of human nature), it’s a question of identity. The answer to finding one’s identity anywhere other than Jesus is to see that Jesus is better. The news that Jesus is better than sex, is what makes the Gospel good news for the same sex attracted (and people who are opposite sex attracted).

Our sexuality is a small illustration of the perfect and whole intimacy we’re made to enjoy as part of God’s kingdom in a marriage-like relationship to Jesus himself. Heterosexuality is not the ideal, it’s good, but it’s the bridge to what we’re ultimately made for.

3. By speaking as though all gay people are represented by a “gay lobby” hostile to Christianity, Born This Way treats gay people as the enemy or the “other”

This book is combative. It feels like a book calling people to gird up their loins in the face of this conflict. It feels like a guide to being the Church against the world. Even in its attempts to be winsome, this book is like the Queensberry Rules for fighting against the pervasive influence of the “gay lobby” and stopping more people becoming gay.

The book tries to redefine common terms in the discussion around homosexuality to make them more objective or technical. It’s an interesting approach. We believe it fails for a number of reasons which will hopefully become apparent below. The big issue is that loving people often requires listening to and understanding them, and finding points of engagement within their own framework, not simply telling them that their chosen terms are all unhelpful and trying to wrest the control of the discussion out of their hands. The move also seems to trample over the work that groups actively engaged in ministry to people who identify as homosexual or experience same sex attraction have done in doing exactly this sort of loving engagement.

The problem with this combative approach – whether its treating the “gay lobby” as an enemy to be destroyed, or simply emphasising the distance between gay people and normal people – the sort of people you’d play cricket then talk to about “the gay issue” (page 15) – is that it makes gay people seem less human than “normal” straight people. The book talks about those homosexuals as if they’re an entirely different category of person.

Mitch: At this point every person living with same sex attraction is ‘they.’ We’re ‘those people.’ Most gay people like to be associated with the gay lobby about as much as most Christians like to be associated with political Christian lobbying.

Gay people are not the enemy of Christianity. They are not other. They are our neighbours. Every one of us is broken by sin, biologically broken. This brokenness extends to our sexuality, even if our sexuality is “by the book” in a heterosexual marriage, but without transformed hearts, our sexuality is the expression of hearts that the Bible diagnoses as broken and selfish. Straight sex is closer to the way we were created to experience sex, but it doesn’t make anybody any closer to God.

Being attracted to someone of the same sex does not make another person the enemy. If all homosexual people were aggressively anti-Christian then this approach might have merit. But until the guy across the street from me stops making snide comments about the gay couple two doors down, gay people are in a minority that makes them vulnerable and we (as the book acknowledges) need to love homosexuals. I think we do this because they’re our neighbours, not because we’re told to love our enemies.

Morrison appears to position the gay lobby, and the society that forms around its agenda, as our enemies who are engaged in a battle for our hearts, minds, and private parts —his fear seems to be that by normalising homosexuality they will create more homosexuals (or at least more homosexual sex). It may well be the case that the gay lobby, like any group of people who want people to find their identity in anything but Jesus (the Bible calls this idolatry) is opposed to God. But they are no more opposed to God than myriad other idolatrous voices in our society that we don’t treat as enemies or “other” in this way. We love them as our neighbours and hold out the good news of the Gospel to them, while pointing out the dangers of idolatry. This book goes further. It goes to war with idols, an approach more at home with Israel in the Old Testament (within the Promised Land) than with the Church in the New Testament. When Paul encounters a city full of idols, he uses these idols to show that idolatry is hollow, especially in comparison to the living God (Acts 17).

The book expects these enemies, or others — and those tempted by their lies — to be conquered as they’re lovingly presented the objective facts of science and the Bible, and to quit homosexuality like a smoker quits smoking. These pieces of objective data are important, but they aren’t what will ultimately help win someone to Jesus.

All the implications Morrison draws in the following quotes from Born This Way are true, but they’re true whether you approach gay people (and those passionate enough to lobby on gay issues) as neighbours, not enemies.

“Jesus tells his followers: “You have heard that it was said, ‘You shall love your neighbour and hate your enemy. But I say to you. Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you.” (Matt 5:43-44) Jesus is very clear on our response to those with whom we disagree. Sometimes a disagreement can be so strong that we are even inclined to call the other person our ‘enemy.’ But no matter what views you hold, other people are to be treated with love and respect. This means that the past decision to classify homosexual attraction as a psychological disorder was not acceptable. Future research will no doubt help us understand the psychological factors involved, but at present there is no evidence of homosexuality being related to any kind of disorder, and the Bible never places homosexuality in that category. Prejudice against those who have homosexual attractions is out—as are persecution, discrimination, mistreatment and hatred. It should go without saying, but any form of physical violence is also completely unacceptable.” — Page 25

“…because God welcomes the homosexual, we welcome them too. Our churches are full of people who have all kinds of sinful histories—in fact, there is no one in our churches whose history isn’t littered with sin, our churches are full of people who are tempted by the same sex, and so we welcome them into our congregations just as we welcome those who struggle with slander, pornography, greed, and any other sin. When our churches welcome visitors who struggle with sin—even practising homosexuals—that doesn’t mean we are condoning their sin. We are offering grace, mercy, truth, forgiveness and community, in the same way that we offer those gifts of the gospel to all human beings…What we must not do is say (either, explicitly or implicitly) that a person who struggles with homosexuality is not welcome in our church until they get their Iife sorted out. In the same way that you came to God with sin and struggles, so does everyone else.” — Page 124

Mitch: If you read this as a homosexual person investigating Christianity, where it talks about “the homosexual,” you’d feel like the subject of a narrated National Geographic documentary.

4. Born This Way is “not really a pastoral book” — which is irresponsible

It’s not just gay people outside the church who cop bullets from this book’s combative approach. There’s friendly fire too. It hurts people in our churches who are same sex attracted (for reasons discussed below).

This pain, in part, is caused by the book’s bloody-minded approach to this issue. As though the science and the Bible can ever be talked about in a way that is disconnected from real people and their experience. In the book’s online promo video Morrison says:

“The book is not really a pastoral book, I haven’t principally written it for people struggling with same sex attraction, I do deal with it a bit and I know they’ll be reading the book, but really what I’ve written for is for people to understand the Bible in a world made by God, but in a world in rebellion to God.” —Steve Morrison, Promo Video, Born This Way

This is one of the biggest failings in the book. It’s ignorant to think that it’s ok to write a book about an issue that has such a profound impact on people, including mental health impacts — Christian or not —without being pastoral. It’s a mistake to think that this debate, about something as subjective as a person’s experience of sexuality and where it fits in their identity, can be solved with objective, impersonal, truth.

If this issue is a big deal for real people you’d expect Christian people who want to deal lovingly with this issue to do more than just treat it with dispassionate objectivity. The decision not to write in a predominantly pastoral voice is a vexing one, especially given the marginalisation Same Sex Attracted people feel both in society and the church. And that, in my mind, is one of the biggest failings of this book. It tries to dispassionately deal with this issue without an eye on the real people affected and the harm writing this way might cause.

This, frankly, seems unloving. Sure, it’s loving to deal in facts and to present truth, but listening and understanding is also loving, and I’m just not sure this book is an exercise in demonstrating a commitment to listening to those who are same sex attracted so much as telling them how life really is.

I don’t know that it’s possible to write a Christian book that attempts to teach Christians how to navigate a complex issue dealing with sin, brokenness, and our humanity, that is not pastoral.

This decision to approach the book this way actually creates most of the subsequent problems in this list. It’s not just the content that lacks a pastoral approach. The publisher says Steve was in contact with people from ministries to same sex attracted people, including Liberty Inc, about the book. However, to our knowledge, nobody currently involved with Liberty, who are probably the leading evangelical group counselling Same Sex Attracted Christians, was aware this book was being written or released (Matthias Media did contact Liberty’s pastoral worker in Sydney UPDATE: Liberty’s pastoral worker in Sydney, Allan Starr, has now reviewed the book).

5. Born This Way compares same sex attraction to the biological urge to smoke, and same sex sex as the equivalent to smoking

This is where the book dies. The author makes the unhelpful comparison between homosexuality and smoking (remember when the ACL made a comparison between the health impacts of smoking and the homosexual lifestyle). This comparison is loaded, it is fraught with baggage, and it is completely foreign to the experience of those living with same sex attraction. This is where it becomes exceptionally clear that this is not a pastoral book, and it’s where the book shifts to becoming an overtly unhelpful book for same sex attracted people.

“Take smoking as an example. Since smoking a cigarette is not condemned in the Bible, we cannot condemn it as being sinful—provided it’s legal, and not against your conscience. It may be unwise—even very unwise—but the action is not sinful in and of itself. Of course, therein lies a crucial difference between homosexual activity and smoking—one is explicitly prohibited by God’s word, and the other is not. But they are similar in one important way: societal expectations and pressures have changed over time (but in opposite directions).

In different parts of the world and at different times, people have faced varying temptations to smoke… When I was growing up in the 1980s, smoking was far more culturally acceptable than it is now. There were TV ads for smoking, and it was considered trendy and tough for most kids to smoke. So many young people took up smoking, to varying degrees. But if you are born in Australia today it is much less likely that you will face a strong temptation to smoke. From kindergarten onwards, impassioned health campaigners will teach you about the dangers of smoking. In 21st-century Australia, smoking has become socially far less acceptable than in years gone by.

Now take two people who have quite different genetic predispositions to want to smoke. If both were in Holland in the 1940s, they may well both have been smokers. If both grew up with me (lucky them) there is a good chance that both would have tried smoking, even if only one or two cigarettes… But if both people were growing up In Australia today, there is a strong probability that neither of them would ever smoke. The two people’s desires might still be very different from one another, but their decisions and actions would be shaped by their life situations. So while the number of people being born with a genetic tendency towards smoking shouldn’t change, proportionally, we would expect the number of people smoking over time to vary, depending on things like our society’s attitude to smoking, and the growing evidence about the harmful effects of cigarettes.

The statistics tell us exactly that. For example, in Australia in 1945, 72% of men and 26% of women smoked regularly. In 1980, 41% of men and 30% of women smoked regularly. And by 2010, that number had dropped to 22% of men and 18% of women.

So we should expect a similar type of thing to happen with homosexual activity—but in the opposite direction. The proportion of people genetically predisposed to SST should stay the same, but the actual number of people tempted to engage in (and actually engaging in) homosexual behaviour will vary. For this reason. It is very helpful to view SST not as something restricted to a finite proportion of the population, but rather as a potential temptation that all Christians should understand. —Born This Way, Pages 101-103

The argument here is that if our society buys the view of homosexual sex (not relationships, or identity) presented by the nefarious gay lobby, then more people will have gay sex. It seems to wrongly assume:

- That belonging to the smoking community and the gay community are qualitatively similar.

- That nobody experiences exclusively homosexual attraction, or at least we aren’t talking about those people any more, just people who are on the spectrum in such a way that this sort of experimenting becomes likely (and spreads further along the sliding scale of sexuality).

- That there are statistics showing that gay sex, or the number of people identifying as homosexual is on the increase (and that this is not simply a normalisation of the statistics as a result of reduced social stigma, where people who once might have stayed in the closet are coming out).

- That it’s a simple, and contagious, temptation that’s a potential temptation for all Christians.

- That gay people don’t smoke, so can’t recognise the difference between these two urges or temptations as they read this argument.

These false assumptions lead to false (and harmful) conclusions.

6. The smoking analogy is bad by itself, but it prevents the book from dealing with why Jesus is better than sex.

Mitch: Most Christians who deal with same sex attraction see themselves as primarily Christian, and approach their sexual orientation accordingly. But, while they make this sacrifice for the sake of the Gospel they look at their friends who get to be Christian, straight, heterosexual, fathers, husbands and boyfriends. They get all those other things that give them a clear role and place in their church and community. These are things that fill out belonging and identity. Sure, they’re not primary, but they go a long way.

Yet, SSA Christians can’t have any of those, nor any of their own version of those. In fact this book tries to even pronounce a more correct way for SSA people to label themselves. We’re allowed to be Same Sex Tempted now, but not same sex attracted. I think we’d almost prefer Paul’s ‘homosexual offenders.’

The truth is there will be a number of people who want to settle with or sleep with someone of the same-sex until they die. That doesn’t mean it’s right, but it’s over realised eschatology to pretend it’s not the case. The real issue here isn’t the science, it’s relationship. SSA men and women want to desire people and be desired. They want rich, intimate, mutual love. They want to be proud of it. They want to feel free in it. They want it to last. Don’t you?

They want what the Trinity has. They want what the Gospel opens the door to. This is where the Gospel is good news for Same Sex Attracted people – it redefines natural longings, and redirects them to their created purpose. It offers genuine satisfaction and wholeness.

There’s just not enough of this in Born this Way, and it makes the tone of the book seem uncaring and disconnected.

7. Born This Way is a product of crippling unexamined ‘privilege’

Nathan: I’m massively opposed to the way the spectre, or rhetorical trump card, of “privilege,” has been used recently to silence voices in conversations dealing with sensitive issues and vulnerable minorities. People who aren’t directly affected by sensitive issues have contributions to make on these issues — so, for example men legitimately have much to say about the injustices identified by feminism, and need to speak into those issues. Jesus was single and spoke about sex. You don’t have to experience something first hand to have a contribution to make. But there is a gap that needs bridging from author to reader when the author isn’t standing beside the reader in their shoes.

As much as I hate the “privilege card,” I feel, reluctantly, that this book never really gets over the problem of Morrison’s apparent unacknowledged privilege. He is presented in the book as a heterosexual, married, man. It may be that he is same sex attracted as well, and choses not to acknowledge it because it would undermine the book’s objectivity (which seems very important to its argument), if this is the case it is one way the book is crippled by its objective scope. But we are working on the assumption that Morrison, because he never says otherwise, is not same sex attracted.

Morrison writes from a position where he presents himself as someone objectively tackling this issue by objectively dealing with the two important streams of revelation and authority on this issue – the Bible, and science. But this position of authority isn’t the only privilege involved. He writes as a heterosexual man who is a church leader. He doesn’t have to make drastic changes to his own life, his behaviour, or his identity, as a result of his findings. He’s essentially telling people they need to become more like him (even if he doesn’t say it this way), without really being able to understand, first hand, where they are being asked to come from.

Heterosexual people who are in positions of influence —leadership positions — in our churches have an incredible responsibility to be sensitive to the people in our care who are vulnerable because of their sexuality. In church communities where heterosexuality is often held out to be the normal, pure, sexuality, our heterosexual leaders need to be pretty careful not to speak from positions that don’t take this sort of privilege for granted.

It’s dangerous to talk as though a heterosexual marriage is the path to sexual wholeness, not the Gospel, or as though heterosexual sex, because it reflects God’s good creation in Genesis 1-2, is not broken by the events of Genesis 3.

Every person’s natural approach to sex— the approach to sex produced by our sinful nature— needs to be redeemed by Jesus.

This conversation needs heterosexual leaders speaking up on behalf of the marginalised in our churches, but we also need to listen to the experience and wisdom of our brothers and sisters who are living out faithful lives as same sex attracted Christians.

Morrison tries to do this by regularly including quotes from prominent Christians who are same sex attracted, but there are certain elements of his approach that do not seem to mesh with the lived experience of same sex attracted people, at least not the same sex attracted people I know. This is the danger that comes from writing from a position where you don’t have first hand experience of what you’re talking about, and it’s the danger of pursuing pure objectivity on a topic that is incredibly subjective for people in a way that can not be truly understood by someone who lives that experience as a first hand reality.

The responsibility for those of us who realise we’re entering a discussion from a position of privilege is humility, realising that there’s a subjective realm of information that we just don’t have access to, and that others do, and these others have something to say about how conversations like this should take place.

One application of this sort of humility is to not come in like a rude or awkward dinner guest, who tries to re-arrange the furniture. It’s not our place to enter this discussion and try to redefine terms that have been carefully chosen to describe the reality of life as a same sex attracted person. The worst of these is discussed at point 9.

8. Born This Way tries to find objective solutions to a subjective subject.

This means it doesn’t really listen to same sex attracted people. Morrison’s unexamined privilege and his assumption that a loving tone, couple with the ‘objective’ data and some cherry-picked anecdotes can bridge the gap between his experience and the experience of others, means this book is disconnected from the real world of people for whom same sex attraction is a reality.

Morrison never acknowledges that for many same sex attracted people, even if the data suggests a biological link is only part of the picture, their experience of their sexual attraction is that it is something natural, something that they are born with, something that they do not choose. His simplistic treatment of the data is essentially to argue that since biology is only a small part of the picture the rest of somebody’s sexual orientation is the product of choice. We aren’t disagreeing with Morrison that lust and sexual activity are the products of individual choice. They are. To suggest otherwise would be to insist on a weird sort of slavery to nature, but it’s equally problematic to try to minimise the impact nature has on attraction and temptation, especially to suggest the biological influence on attraction is similar to the temptation to smoke or watch television.

Morrison’s treatment of attraction is so focused on nature that it ignores science around nurture. Even if a homosexual orientation is the product of both biology and environment, it is typically established so early for someone, or by circumstances beyond their control, that it’s too complicated to simply call it a choice. That some people choose homosexuality (as supported by anecdotal evidence) does not mean this is true for all people. The science cannot be used to argue that the desire to engage in same sex sex is similar to the biological urge to smoke or watch television.

Morrison has this binary approach to the born this way question such that the science only really matters if someone is 100% genetically born same sex attracted (and then it only really matters if the person is 100% same sex attracted and not bi-sexual.

“So is homosexuality biologically determined at birth? To date, science’s best answer is that someone who experiences SSA may well have some biological or hereditary factors that play a role in causing this attraction—but to a much smaller extent than is often claimed. While it is widely believed that sexual orientation is genetically determined—in the same way as skin colour, bone structure and eye colour—the best scientific evidence tells us that SSA is in a very different category from those types of hereditary characteristics. Genetic factors like skin colour and eye colour are 100% determined from birth. But there are many psychological or behavioural traits that are only partly determined by genetics. In those kinds of cases, a wide range of other factors will come into play to influence how a person ultimately lives or behaves. For example. one study has shown that a person has an average heritability estimate of 45% to have a predisposed inclination to want to watch television.At the most, male SSA is likely to be hereditary at a rate of 30-50%—very similar to the hereditary desire to watch television…we must understand the genetic, hereditary component of SSA very differently from the way we view an unchangeable characteristic such as skin colour. The hereditary component of SSA is more like a person’s hereditary desire to smoke, eat too much, watch certain amounts of TV, tend towards certain political views, or have a desire to attend church” —Pages 51-52

Nobody I know feels like TV watching, smoking, or eating, is the fundamental basis for their identity. But many people define themselves by their sexual orientation. This is one of our society’s biggest forms of idolatry — we weren’t created to find our identity or humanity in sex, but in our relationship with God. Disconnecting sexuality from identity is a potential way forward in the way Christians talk about homosexuality that doesn’t throw pastoral hand grenades at the same sex attracted.

9. This failure to listen is most evident when it tries to move the conversation from attraction to temptation

“It’s important that we distinguish carefully between three words relating to homosexuality: ‘action’. ‘lust and ‘attraction’. A homosexual action is when a person engages in sexual activity with someone of the same gender. Homosexual lust is when someone has fantasies and passions that express themselves in imagining homosexual situations. The third category is attraction. This is different from lust, and we must continue to distinguish between attraction and lust because of the question of choice.”— Born This Way, Page 35

But sometimes our desires or attractions draw us towards things that are wrong in themselves. Same-sex attraction is like this. It’s a disordered desire or attraction towards something that is wrong in itself, and so it should always be resisted. In this sense, it’s helpful to view a same-sex attraction as a temptation, as something that needs to be resisted lest it lead to sin. There are a number of advantages to replacing SSA with SST. The first advantage to using the language of ‘temptation’ is that it allows us to clearly say that acting on the attraction is sinful. It removes the ambiguity of ‘attraction’ or ‘gay’, and places the idea of ‘attraction’ in the category of things that a Christian needs to resist. Another advantage in calling the phenomenon ‘temptation’ is that the Christian can assert—even more strongly and confidently than the scientist, in some ways—that a person who experiences attraction to the same sex is, indeed, born with SST. The Christian doctrine of original sin says that every human being is born with “a motivationally twisted heart ” — Born This Way, Page 99

Same sex attracted people who follow Jesus aren’t called to stop finding people of the opposite sex attractive; to lobotomise that part of their brain. Same sex attracted people are called to find their identity in Jesus and so not to turn attraction into lust, or attraction and lust into action.

Temptation is how the gap between attraction and lust, and between attraction and lust and action, is bridged.

Attraction isn’t the same as temptation and by insisting that it is, and that it should be fought, Born This Way robs same sex attracted people of a part of their humanity in a way that we don’t do this to heterosexual people.

Have you ever heard a heterosexual Christian be told to not be attracted to someone of the opposite sex (as opposed to not lusting after them)?

Mitch: This is the single most offensive part of the argument, particularly to those who find themselves exclusively and continually attracted to the same-sex. They have all the identity and relational tools afforded to straight people taken from them. Morrison doesn’t say anything about what the Gospel does to our heterosexual attraction, except to affirm it as approved by God, so those who are opposite sex attracted are allowed to keep saying they find people attractive, and admit their attraction to people (without being told this is necessarily broken opposite sex temptation). The heterosexual person is just wired this way, and allowed to live according to their biological wiring (as though it’s untainted by sin). But the same sex attracted have to deny they experience this attraction in any form? I’m probably becoming more convinced by someone like Wes Hill who just says call yourself gay but qualify it as a witness to the gospel, so he says he’s a celibate gay Christian.

10. Because Morrison doesn’t speak from the experiential reality of same sex attraction, Born This Way doesn’t speak of sexual attraction in a way that speaks to the experience of the same sex attracted.

Born This Way simplifies the sexuality spectrum, it treats sexual attraction like a switch, and seems to insist that people who are bi-sexual aren’t really gay and can just flick this switch.

“Science is telling us that the vast majority of people who experience attraction to the same sex also experience some level of attraction to the opposite sex. That is, the vast majority of people who identify themselves as ‘gay’ are actually bisexual. So we find the word ‘gay’ fairly useless, not to mention potentially offensive… There are simply too many categories. too many nuances, being covered by the one word. Let’s take an extreme example and an extreme analogy: how do we compare a person in an active, open, long-term cohabitating homosexual relationship to another person who is in a heterosexual marriage but who once felt a slight attraction to someone of the same sex? Do we call them both ‘gay’?”… The word ‘gay’ is used broadly to summarize any aspect of same-sex attraction, lust or action. But in a conversation where objectivity and accuracy are vital, we need to be more accurate about which aspect of the phenomenon we are talking about. People are free to identify themselves as ‘gay’ and then explain what they mean by that term, but the word is too ambiguous to be of use technically or as a label.” —Born This Way, Page 33-34

“But perhaps the biggest problem with the binary assumption that a person is born either gay or straight is bisexuality.”— Born This Way, Page 54

Morrison treats bi-sexuality as a big deal for his argument. It’s really not. I do not think the word means what he thinks it means. This is only the “biggest problem” and a “binary assumption” because Morrison has earlier redefined “gay” to not be a label that can “technically” describe the identity of a bi-sexual person.

Once he ‘establishes’ this conclusion, and the related conclusion that only one in four gay men, or one in 16 lesbian women, or about 1% of the male population are homosexual rather than bi-sexual (page 55), he reaches an interesting conclusion from this data:

“One helpful way of understanding sexual attraction is to think of it as a spectrum upon which every person appears, and when it comes to same-sex attraction, the genetic influence upon a person’s position on that spectrum is minor, at best. Put simply, if we use the terminology in the way in which it is normally used, a person is not born gay.”— Born This Way, Page 56

But what about the one percent of people who don’t experience a broad part of the sexuality spectrum? What about the one in four gay men who identify as 100% same sex attracted? Who are not, even according to his data, bi-sexual? How does this conclusion not simply further marginalise the already marginalised?

Conclusion: This is not the book the church wants, or needs, about homosexuality

While there is much to like in this book, and Morrison has set out to provide a resource that will benefit Christians confronted with a world that is increasingly hostile to Christianity and the Biblical view of sex, the problems with this book, problems that will be immediately apparent to those who experience same sex attraction and anybody who understands what it is that people who identify as homosexual are seeking through their relationships, means it fails as a resource.

It is not a book we can recommend. It’s not a book that people who minister to Christians trying to figure out the implications their sexuality has for their faith can recommend.

Nathan: I’ve written about another way Christians can approach what Morrison calls the “universal lie” of “born this way” elsewhere. It requires acknowledging that we’re all born this way, all born with a sexuality that deviates from the sort of relationships God created us to enjoy. It requires acknowledging that we’re all born desiring the same love as one another, however that manifests. And it requires us to acknowledge that we are reborn, and our understanding of love transformed, through the death and resurrection of Jesus that frees us from slavery to our natural, broken, humanity.

Mitch: If people want to read just one book on this issue, and a book that pitches at about this level that is helpful then I would recommend Is God anti-gay? by Sam Allberry.

by Sam Allberry.

Steve’s Response (updated September 2017)

“Dear Nathan,

Thanks for this review. It’s really helped my sales in QLD and beyond. Can you please also review my new book “The Path of Purity”? It’s not getting great sales north of the NSW border yet…

Thanks”

One might assume the drop in sales for book two is because people read the first book and found this review accurately reflected its content.