In the last two posts I’ve explored how the practice of destroying statues — the damnatio memoraie — is an ancient one, and how public space has always been sacred and contested (and how when Jesus turns up in a contested public space, both sides of the contest joined sides to kill him).

There’s a picture of this for those who would follow Jesus in the book of Revelation; John’s apocalypse. Up front John writes to some churches in the Roman world. He pictures these seven churches as lamp stands. Churches who are meant to bring light to the world as they reflect the glory of Jesus. By the time you get into the ‘apocalyptic’ stuff — the vivid picture of life in this world that John offered, the seven lamp stands are reduced to two. Two faithful churches — witnesses to Jesus — are pictured as martyrs, and we’re told they speak up, and the beastly world kills them, celebrating the sacrilegious erasure of their voice from the public square like first century statue topplers. John says, of these witnesses, “their bodies will lie in the public square of the great city — which is figuratively called Sodom and Egypt — where also their Lord was crucified” (Revelation 11:8). To follow Jesus in the world is to be treated like Jesus because we act like Jesus because we worship Jesus.

The book of Revelation serves up a picture of beastly worldly power as opposed to God; it ties Sodom, Egypt, Babylon, Rome, and Jerusalem together as pictures of an economically motivated monster opposed to the kingdom of God; in love with the things of this world, and the prince of this world, Satan. The desecration of these faithful churches — these bodies pulled down in the public square is paralleled with the desecration of Jesus, the image of God, in the public square of Jerusalem.

It’s fascinating that the debate about the tearing down of statues — images cast in metal or stone — in public squares around the world — the outpouring of anger of the sort evoked by sacrilege that we’re hearing from one side of the ‘history wars’/’culture wars’ divide because statues-as-history are being destroyed in such a sacrilegious manner, and the outpouring of anger we’re seeing from the other side of the same conflict in the desecrating destruction these of statues happened at the same time that the President of the United States so ‘sacrilegiously’ (or desacrilegiously) set himself up as a pixelated image in a brazen photo opp on the footsteps of a church.

Trump’s photo opp was straight out of the playbook of the Greek king, Antiochus Epiphanes, whose cultural and religious conquest of Jerusalem was framed by the writer of the inter-testamental book 1 Maccabees as “the abomination that causes desolation.”

And perhaps the most distressing part of this scene was not Trump’s following the image-erecting playbook of the idol-kings of the ancient world; it was the way he was cheered on by the faithful — the sort of lamp stands in Revelation who forsook their first love, Jesus, to cosy up with the Beastly Roman empire; the new Babylon, Egypt, and Sodom.

Revelation is apocalyptic literature. Apocalypse just means ‘revelation’ — it’s not pointing to some future moment of cataclysmic end times so much as revealing the cataclysmic results of siding with anybody but God; given that ultimately the victory of Jesus won at the cross will turn the whole world on its head. Revelation talks about the Spiritual reality behind political realities; there is no ‘secular/sacred’ divide — everything is religious; every political act is an act of sacrilege or sanctification — an act of elevating some thing or other to holy status, or applying a religious paradigm to the organisation of life in the world, in terms of how we organise communities of people and how we make and enjoy created things. That those kingdoms that set themselves up to oppose Jesus because they love money and the things of this world are collectives of people — systems, structures, cultures — that have rejected Jesus and picked Satan. Instead of being bearers of the divine image — and so being treated like Jesus and executed in the public square; they’re joining with corrupt power in order to reject God’s king and kingdom, and to destroy their own enemies (those who would take from them the things they really love). In Revelation you’ve got the image of Israel as a harlot, jumping on the back of beastly Rome.

1 Maccabees condemns Israel for not being desperately offended by the sacrilegious act of Antiochus Epiphanes; instead of tearing down the idol and seeking to rededicate the Temple to Yahweh (after Antiochus dedicates it to Zeus), “Many even from Israel gladly adopted his religion; they sacrificed to idols and profaned the sabbath” (1 Maccabees 1:43). Israel’s hearts have been captured by this beastly foreign ruler and his promise of order, and status, and the benefits flowing from belonging to such a powerful empire.

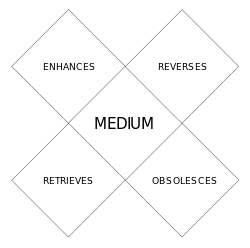

Trump’s photo opp — secured through violent action (this Washington Post composite of smart phone footage and police radio audio puts the idea that he didn’t use tear gas or equivalents squarely in the ‘fake news’ column) — was an act of sacrilege; co-opting the symbols of Christianity — the Kingdom of God — for his own political agenda (so much so that even his military has since distanced itself from the photo opp). This was the digital equivalent of the erection of a statue; a pixelated bust. An image that he hoped might spread frictionlessly around his empire to shore up his rule, and a call to worship his image. In Empire and Communication (1950), Harold Innis argued that empires rose and fell, historically, based on how well and widely they were able to communicate. Statues were an expensive but long lasting way to share an imperial imagery through the landscape an emperor ruled. They were fixed in place, but would last for a long time. They were limited. Trump is the master of harnessing the digital landscape to create imagery and words that spread through the empire; a master of propaganda and pageantry. He doesn’t need statues to spread his image; there is now a permanent picture of Trump with a Bible, in front of a church, engraved in the American pysche. The Roman empire followed other ancient near eastern practice by using coins as propaganda; the emperor’s image was carried in the pockets of the average Roman citizen (see Jesus on coins ‘the image of Caesar’ v ‘the image of God), when Trump wanted his name on the cheques sent out as stimulus to citizens during the Covid-19 lockdown he was again borrowing straight from the ancient playbook.

Just as Revelation depicts a faithful church who stand against the empire and so get slaughtered, 1 Maccabees tells the story that not all in Israel succumbed to Antiochus’ attempts to profane the Temple, while glorifying the image of his gods.

“But many in Israel stood firm and were resolved in their hearts not to eat unclean food. They chose to die rather than to be defiled by food or to profane the holy covenant; and they did die. (1 Maccabees 1:62-63)”

These were the #NeverTrumpers of the first century B.C.

My observations of peers in the U.S who won’t bend the knee to Trump is that it’s more costly within Christian community to refuse than it is for an NFL player to bend the knee during the anthem. Leader after leader seem to be coming forward to pledge their allegience to the Trump re-election campaign; excited by his fusion of the sword of empire with the sword of God’s word… while ignoring the picture God’s word paints of the empire while telling Christians to submit to its authority — to the point of martyrdom; just as Jesus did. Now, this is complicated of course, and people of God are able to be a faithful presence working for change in idolatrous foreign governments — the guiding principle from Joseph, to Daniel, to Esther, to Nehemiah, to Erastus in Corinth, to the early Christians in the Roman empire — seems to be a refusal to worship at the feet of the emperor because Jesus is their Lord and King — their spiritual and political leader. Daniel, the courtier, was chucked in the lion’s den explicitly for his refusal to bend the knee to the king he served. Serving in the courts of the king isn’t the problem — that’s precisely where God’s people can act as a faithful presence to see actions aligned with God’s kingdom (so when Esther doesn’t mention God, that’s not because God is absent in the story, he’s present through the faithful presence of his people). In Daniel, in case the symbolism needs to be any more overt, Nebuchadnezzar literally becomes beastly as a result of the pride he takes in the size and scope of his power.

“Immediately what had been said about Nebuchadnezzar was fulfilled. He was driven away from people and ate grass like the ox. His body was drenched with the dew of heaven until his hair grew like the feathers of an eagle and his nails like the claws of a bird.” (Daniel 4:33)

Trump is the embodiment of the worship of the things of this world. He is beastly in every sense of the word, as the Bible describes it. He is the personification of the vice list in Colossians 3 that Christians are told to put off as they are restored in the knowledge of the image of our creator. Find one thing in this list that Trump hasn’t proudly demonstrated in his tweeting, rallies, and photo opps.

Put to death, therefore, whatever belongs to your earthly nature: sexual immorality, impurity, lust, evil desires and greed, which is idolatry. Because of these, the wrath of God is coming. You used to walk in these ways, in the life you once lived. But now you must also rid yourselves of all such things as these: anger, rage, malice, slander, and filthy language from your lips. Do not lie to each other, since you have taken off your old self with its practices (Colossians 3:5-10)

He is a living, breathing, idol, erecting pixelated statues to himself and inviting all to bend the knee to him (and getting angry when they take a knee to any other god).

But when he stands in front of a church, co-opting it to maintain his position in his empire, church leaders in America aren’t falling in behind the example of the two faithful lamp stands in Revelation 11; they’re the five who left. And it’s appalling. It’s a symptom of a Christian culture that cares more about results and appearance and power than about virtue, and faithfulness, and following the example of a crucified king. It’s the sign of a church who learns nothing from history, because it cares nothing about history; or the role of narrative — both from the Bible, and through history, and its foundational role in shaping character; a church obsessed with technique, coopted by the forms and strategies of the world, because those are the ones that for good and for ill, have provided influence (and, on the whole, less martyrdom).

Christians might ‘bend the knee’ while holding their nose; but there was no space for that in Jerusalem when Antiochus swept to power, and none in Rome in John’s revelation; the faithful church was martyred for its refusal to take a knee. There’s even evidence of this in Pliny’s letter to Trajan. The trial Pliny devised for those accused of being Christians was simple; straight from the pages of Daniel. They were asked to worship an image of the emperor.

“Those who denied that they were or had been Christians, when they invoked the gods in words dictated by me, offered prayer with incense and wine to your image, which I had ordered to be brought for this purpose together with statues of the gods, and also cursed Christ – none of which those who are really Christians can, it is said, be forced to do — these I thought should be discharged. Others named by the informer declared that they were Christians, but then denied it, asserting that they had been but had ceased to be, some three years before, others many years, some as much as twenty-five years. They all worshipped your image and the statues of the gods, and cursed Christ.”

Trajan’s response is a model of reasonableness — he doesn’t want a witch hunt; but, if people are accused of being Christians and fail this test, then they are to be punished.

“They are not to be sought out; if they are denounced and proved guilty, they are to be punished, with this reservation, that whoever denies that he is a Christian and really proves it — that is, by worshiping our gods — even though he was under suspicion in the past, shall obtain pardon through repentance.”

There’s a whole swathe of Christians failing this test; putting Supreme Court seats, religious freedom, political influence, abortion law reform, and victory in the culture wars against the evil “woke left” as justification for joining in Trump’s profanity. But it’s not just the church of the right co-opted by the empire… by the lure of worldly power — they’re not the only Christians lured by the sides going toe-to-toe in the culture wars and backing their chosen champion to the hilt; not the only ones taking a knee… There’s a whole swathe of Christians also failing this test by becoming political and spiritual progressives who deny the resurrection, reject any created norms in terms of biological sex, sexuality, or sexual morality, where allegiance to the institutions of the left seems to require a particular stance on the lives of the unborn, who take on the more radical ‘deconstruction’ aims of the extremes of the left not only to dismantle oppression but the idea of any construction outside the self-constructed authenticity we all want to pursue as tribes of individuals… The litmus test might not be invoking the gods in words supplied by the agents of the empire, but it sure feels close; the Christian leaders who paraded out in lockstep to praise Trump’s strong and god-annointed leadership, and to celebrate the photo, have something to learn from Daniel, from Esther, from the faithful Israelites in the time of Antiochus, and from the faithful churches in Revelation…

Both the ‘Christian right’ and ‘Christian left’ — when they’re expressions of the culture wars, and the fight to control the empire (at the expense of the other) — have forsaken their first love. And it might seem like this is a world away from Australia, and America’s narrative — especially when it comes to civic religion — is a very different animal to Australia; but the same symptoms are there in Australia’s own version of political Christianity; especially, I think, on the Christian Right, with the Australian Christian Lobby and a variety of similar bodies spearheading the charge. There’s, frankly, not enough calling this out from leaders of the institutional church in Australia because our temptation to idolatry is often aligned with the right; we Christians (apparently) want a government that will make life comfortable for us (religious freedom), that will keep the invocation of God’s name in the parliamentary process (the Lord’s prayer), and who will give conservative Christian voices access to the throne room (even if it means justifying a vote for One Nation).

There’s another interesting dynamic to Antiochus Epiphanes and his abomination that causes desolation. The temple he profanes is empty. It’s a shell. It stopped housing God’s glorious presence in the exile. When Solomon builds the temple in 1 Kings, the glorious presence of God shakes the foundations of heaven and earth, and God speaks, as he comes to dwell in Israel as their God. The Temple is the seat of his political and spiritual rule; his footstool in the earth. The curtain in the temple marks off the ‘holy of holies’ — as a sort of boundary marker between heavens and earth.

The second temple never witnesses God’s glorious presence arriving (well, it might, I’ll get to this below); the Old Testament ends in anticipation of God gloriously dwelling with his people again. Israel, with the help of the rulers of Persia, rebuild and rededicate the Temple.

There’s a sense in Ezra that things just aren’t the same; first, people who remember the original temple mourn the difference as the foundation is laid: “But many of the older priests and Levites and family heads, who had seen the former temple, wept aloud when they saw the foundation of this temple being laid, while many others shouted for joy.” (Ezra 3:12), and then, the whole thing launches with a party without any divine intervention.

“Then the people of Israel—the priests, the Levites and the rest of the exiles—celebrated the dedication of the house of God with joy. For the dedication of this house of God they offered a hundred bulls, two hundred rams, four hundred male lambs and, as a sin offering for all Israel, twelve male goats, one for each of the tribes of Israel.” (Ezra 6:16-17)

And that’s it. It goes off with a whimper, rather than a bang. There’s no ground-shaking arrival of God in his house from the thunderclouds. No cloud of glory. The house that Antiochus desecrates has not yet been resanctified; the Day of the Lord has not arrived; Israel is still essentially exiled from God when this house is renovated by Herod, when Jesus turns up as the Messiah and calls it a ‘den of Robbers,’ he turns up as an entirely new temple.

And, just in case you think this is some weird over-reading of a lack of cosmic fireworks in Ezra, the prophets anticipate a future ‘day of the Lord’ when the temple would be restored…

“This is what the Lord Almighty says: ‘In a little while I will once more shake the heavens and the earth, the sea and the dry land. I will shake all nations, and what is desired by all nations will come, and I will fill this house with glory,’ says the Lord Almighty.” (Haggai 2:6-7)

Haggai also has this change coming with a judgment on beastly empires.

“I will overturn royal thrones and shatter the power of the foreign kingdoms. I will overthrow chariots and their drivers; horses and their riders will fall, each by the sword of his brother.” (Haggai 2:22).

The sort of destruction longed for, and promised, in the closing chapters of Revelation. The one that comes when Jesus returns to ‘make all things new’ — the sort of kingdom — political and spiritual — that Christians are now meant to anticipate that allows us to faithfully avoid being co-opted by the empires of this world.

The same Bishop of the Episcopal Church of Washington (the denomination St John’s, the church in Trump’s photo, is part of), Mariann Budd, who said “Mr. Trump used sacred symbols to cloak himself in the mantle of spiritual authority, while espousing positions antithetical to the Bible that he held in his hands,” also said, in a widely quoted (now deleted) blog post “The truth is that we don’t know what happened to Jesus after his death, anymore than we can know what will happen to us. What we do know from the stories handed down is how Jesus’ followers experienced his resurrection. What we know is how we experience resurrection ourselves.” There’s every chance Trump stood in front of an empty house, just as Antiochus re-dedicated an empty house to Zeus. Denying not just the ‘in the flesh’ nature of the incarnation, but the resurrection, was something John (who by-the-by, I think is the same John who wrote the Gospel, and Revelation) had pretty squarely in mind when he talked about anti-Christs in 1 John (see more on this here).

I’m not here to play the theological witch-hunt game or to be a watch-blogger railing against the wishy-washy world of the Episcopalian Church; the bishop might have had a bad day, and this might be why that post is now deleted and the quote found circulating elsewhere on the interent. As an Aussie Presbyterian, I don’t have a dog in that fight. But the left hand side of the culture wars demands allegiance just like the right does; you get to be part of an empire on that side if you give up the spiritual reality of the Gospel in order to pursue the political vision of justice that was part of Jesus’ kingdom. Christians explicitly taking sides in the culture wars — championing or being championed by visions from the left, or the right, end up doing eschatologically odd things, and aligning themselves with empty temples. You get a pass from the left for championing feelings and desires above the created reality of our bodies, and the ‘feeling of resurrection’ over the embodied reality of resurrection, and the goodness of humanity over the darkness of sin and God’s holiness and so the reality of judgment (and exile from God). You get a pass for the left for sharing its political vision, and so sharing its spiritual vision — because there is no secular/sacred divide. You get a pass for totally over-realising your eschatology; and, just like the right, seeking to build your vision of the kingdom here and now through whatever levers of power are on offer. So you play your own part in the culture wars, and bend your knee to your own alternative gods when you should stand. And yet, again, a caveat — Christians can be faithfully present in the institutions of the left, just as they can in the right, the question, ultimately, is about allegiance (and one of the signs for who your allegiance is to might be in how you make space for Christians on the other side of the political fence).

We followers of Jesus should have no part in sacrilegious abominations that are not the destruction of our own image in the same way that the image of God was destroyed in first century Israel, in the public square of that beastly city. We’re not meant to jump on board with the erection of other images that represent worldly power; not to nail our colours to those masts; not to bow the knee to other emperors — we’re to stand, and die, with the one who stood and died for us. To pick a side in the culture wars is to pick an idol, and to sign up for a particular form of iconoclasm, and a particular form of idol construction. And the Bible consistently calls the people of God away from idols because to participate in such image making conforms us into a particular image… As Psalm 115 puts it, when it comes to idols, “Those who make them will be like them, and so will all who trust in them.” You lie down with dogs, you get fleas. You side with Antiochus, you get the Pharisees executing Jesus. You side with Satan, and the rulers who rule using his playbook, you become beastly. You follow Trump and suddenly you lose all public credibility when preaching Jesus. You join young Martyn and his political revolution aimed at securing access in the corridors of power through endorsing One Nation, and you get… And here’s the thing, you sign up as a card carrying supporter of Black Lives Matter, the organisation (as opposed to participating in the conversation and using the statement)… well, it’s very likely you’ll be conformed to its view of the world. The trick is figuring out how to be in an empire but not of the empire; to serve in the government of Rome without worshipping the emperor. To work in the public service without campaigning for the leader, which is hard — a lesson a certain general, and stacks of other ex-Trump staffers have learned the hard way: you refuse to be in the photo opp, or facilitate it, you say “no,” you differentiate yourself in words and actions, you speak up clearly and with conviction to call out bad behaviour, you recognise the good and the humanity not just in your own side, but the other, you love your enemy and practice forgiveness, you draw a line and you hold it with integrity, you preach Jesus even rebuking those in power on your own side, when it costs you everything… You stand when you’re called to bow. And look, I get that my friends on the right see that this is an issue with Black Lives Matter TM, and so don’t want to take a knee — but I’d like them to take the same stance when it comes to those idolators on the right, not stay silent when it suits them. You stand against racism and for the plight of the marginalised and oppressed; and you stand for J.K Rowling as she gets cancelled. You do both. 100%, or 50-50, not chucking stones at the other side and its excesses with a caveat about the goodness of their diagnosis of the issue, not defending the excesses of your side with a caveat that Trump is really bad “but”… You use “and” instead of “but” — a pox on both their houses… Both houses are empty.

Revelation 11 gives us a picture of faithful image bearers of Christ, and what that looks like in the public squares of beastly empires.

They’re dead.

Killed. Hated. Rejected. Mocked. By everyone.

Right and Left, without Jesus, are just beastly versions of the same beastly game of rejecting God in favour of self; both are insidious expressions of and co-opted to a political system that loves money and power and autonomy; both are idolatry.

We might well get thrown to the lions, but not bending the knee, is also how to patiently and faithfully bring about the sort of change and reform that shook the world, it’s also what we do in the hope of real, embodied, resurrection.

Choosing either side of the culture wars has a cost for our faithfulness, and deforms us into false images of false gods… and I’ll explain in a future post why I write so much more about the dangers from the ‘right’ and Trump, than from the left… but for now let me conclude by saying that Trump’s photo opp, like the original ‘abomination that causes desolation’ is the product of the fusion between the political and the spiritual; there’s no secular/sacred divide.

Trump’s photo opp was a profane and idolatrous act as he sought to glorify himself by creating an image to spread through and support his empire; and that should be massively problematic for Christians, and we should faithfully speak out not just in opposition to that, but to testify to the same Jesus who was executed in the public square of a beastly city by religious people who should’ve kept the faith, but whose track record was being the descendants of those who did not oppose Antiochus. How could they do anything but cuddle up to worldly power?

If you’re upset about statues of ancient white dudes being toppled, but not by this old white dude erecting pixel images of himself while surrounded by symbols of Christianity, then I think you need a little more iconoclasm in your diet.

Images are powerful. That’s precisely why not only are those statues ‘powerful’ — but the pictures of statues being toppled get sent around the world.

And if you can’t bring yourself to condemn Trump’s image-building, without qualification, as an act of political beastliness, rather than godliness — I’d ask you to check your motives. Your enemy’s enemy is not your friend. The lesser of two evils is still evil (and may actually be the greater danger if you can’t call it evil). Trump’s image, because we’re now in the digital age, is likely to be harder to remove than a statue. It will be reduplicated and distributed as part of the historical record; unlike a statue, it’s going to be very hard to erase.

When it comes to the culture wars, without a differentiated Christian presence challenging the idol building game, the temples on both sides are empty; devoid of life and the presence of God. A St. John’s without the proclamation of the Gospel of the resurrected Jesus, if indeed this is the case, is a profane building already; empty and de-sacred (‘desecrated’). God is present through his Spirit; his Spirit is present in those who recognise and proclaim the resurrection and Lordship of Jesus. Trump’s digital statue exercise and rededication didn’t significantly change its spiritual state.

Israel’s exile from God didn’t end with her return from exile; the captivity of their hearts continued. The return, and even the building of an inadequate, empty, temple was a precursor to God’s plans to return to his people and re-create us in his image again; to give us new hearts. The day of the Lord required an empty Temple, so that god’s presence might fill his new temple as his spirit created new images.

And that happens with the coming of the Holy Spirit in Acts 2. I think, for some reason I’d always pictured this moment at Pentecost happening in “the upper room” (because the events of Acts 1 happen there). But Luke is at pains to tell us that the disciples practice was to ‘meet daily in the temple courts’ (Luke 24:53, Acts 2:46). The events of Pentecost happen in front of lots of people — heaps more than you’d expect in an upper room where the disciples met in Acts 1. There’s chronological distance between Acts 1 and Acts 2. So I think the events of Pentecost happen in the empty-of-God’s-presence Temple; the Temple that was judged when the curtain tore, that has no claim on being the dwelling place of God because of the way Israel participated in the ultimate desolating abomination (the destruction of Jesus).

There, in the temple that had been waiting all those years to be renewed by God’s presence coming back, God’s presence comes to those who believe in the resurrection of king Jesus. It comes in the same glorious firey way that God came into the Temple in 1 Kings, only it lands not in the holy of holies, but on God’s holy people. People made holy (sanctified… made ‘sacred’), by the Holy Spirit. Holy just means ‘set apart’ from the beastly people around them. The Holy Spirit is what gives animating life to God’s living, breathing, images — the representatives of his kingdom — as we live in the world as his ambassadors; those who might be present in the corridors of power in different empires, but who won’t support or bow the knee to the elevation of abominations — those who call people to worship something other than the living God. To pick a side in the culture war — to choose an empire with its associated imagery — and to be excited or upset about the image games played by your side (or the other) — is to choose an idol.

One way to avoid the appearance of picking a side — even while seeking to be a faithful presence within an empire and its machinery — is to call out this idolatry, the idolatry of your own particular political ideologies or inclinations, another is to keep faithfully proclaiming the death resurrection of Jesus and seeing his kingdom as one that challenges the beastly regimes of this world so much that they put him to death; such that to follow him means a commitment to a certain sort of martyrdom; to being desecrated by the world.

As John himself puts it in 1 John…

“We know that we are children of God, and that the whole world is under the control of the evil one. We know also that the Son of God has come and has given us understanding, so that we may know him who is true. And we are in him who is true by being in his Son Jesus Christ. He is the true God and eternal life. Dear children, keep yourselves from idols.” (1 John 5:19-21)