Could this be the first Christian Old Spice Parody? It’s pretty impressively made, and at least as good as the Library parody… and it was made between the ad being made and Old Spice’s day of viral madness.

Category: Christianity

This (the Devil) is why you’re fat: update

You might be wondering where part two of my book review is. And so am I. More correctly, I’m wondering where the book is. I can’t find it. Maybe the devil stole it.

I’ll keep you posted. Hopefully.

In the meantime, enjoy this profound spam comment left on my last post:

“Think of how retarded the average guy is, and realize halve of them are stupider than that.”

The cult of Mac

Some people take their Mac fetish to a spiritual level – and it seems with good reason. There’s probably a conspiracy theory book in this. Apple has styled itself as a religion. Maybe.

Here are some potential “religious elements” identified in an interesting study, covered in this article from the Atlantic, entitled: “How the iPhone Became Divine: New Media, Religion and the Intertextual Circulation of Meaning“, it followed an earlier study on “The Cult of Macintosh.”

- a creation myth highlighting the counter-cultural origin and emergence of the Apple Mac as a transformative moment;

- a hero myth presenting the Mac and its founder Jobs as saving its users from the corporate domination of the PC world;

- a satanic myth that presents Bill Gates as the enemy of Mac loyalists;

- and, finally, a resurrection myth of Jobs returning to save the failing company…”

The scholar responsible for that article summed up the Apple experience:

“When you’re buying into Mac, you’re buying into an ideology. You’re buying into a community.”

It’s funny. In a day and age where the church is trying to figure out how to learn from Apple, Apple seems to have flipped the metaphorical apple cart – in basing its business practices on the church.

How to learn Greek and Hebrew on the Mac

Step one: Download Paradigmatic – a great resource for college students by a college student (now former college student).

I’ve only grabbed it today, but it comes highly recommended by people in the know.

Sam Freney, the whizz in question, has also produced a Greek lexicon for the iPhone available here, or via iTunes.

Two truly terrific resources. Grab them today. They’re probably worth getting a Mac for (if you’ve been trying to justify a purchase).

How to pick a church slogan

If you’re in the business of picking church slogans you don’t want to go cherry picking passages willy-nilly. The U.C.C is not famous for caring what the Bible actually says, so it could well be that they were aware that these words actually come from the mouth of Satan when he’s tempting Jesus in the desert.

The tagline reads “if thou therefore will worship me, all shall be thine – Luke 4:7″…

Luke 4:7 in context reads:

5The devil led him up to a high place and showed him in an instant all the kingdoms of the world.6And he said to him, “I will give you all their authority and splendor, for it has been given to me, and I can give it to anyone I want to. 7So if you worship me, it will all be yours.”

8Jesus answered, “It is written: ‘Worship the Lord your God and serve him only.’

I reckon verse eight is a better starting point.

Via Nathan Bingham.

What do you get when you mix nerds and heretics?

As earlier reported, the Westboro Baptists picketed a comic convention this week. Which is pretty dangerous territory.

They fought signs with signs.

Liveblog: Ben Witherington III on Acts

Ben Witherington III, blogger, biblical scholar and widely published New Testament author, is guest lecturing at QTC today on the book of Acts.

I’ll be updating it as the three hours of lectures go on – check back in this arvo for the final version. What follows are bits and pieces from his lectures:

One of the things I would want to stress to you is that what we’re dealing with in Acts is a form of ancient historiography. Luke is writing in the traditions of Hellenistic and Jewish history writing that had their own conventions which are not identical with the conventions of modern historiography.

One of the great problems with interpretation of the text is anachronism – reading our concerns, our modern concerns, back into the text. Acts is one of the main areas where this happens.

For example: Acts 2 is about a miracle. The miracle of speaking in tongues. But it’s ultimately about empowering the church for mission, not about a particular kind of post-conversion spiritual experience that we will all receive.

All of us are guilty of anachronism – we all read the Book of Acts with modern eyes.

Hermeneutically speaking we need to have some rules about how we read Acts.

- If we find a repeated pattern we can assume this is normative.

- If we find a special event not repeated it might be an unusual historical occurrence and not a principle on which we should hang out shingle.

- Does the author of Acts affirm the pattern? Positive repeated patterns are a good interpretive rubric (the telling of Saul’s conversion as a very important event is told three times – clearly it’s important). Does the author of Acts condemn the pattern. Some texts are “go and do likewise” others are “go and do otherwise.”

- We can’t just deduce doctrines from the reporting of history unless we have other methodologies – Acts reports what happens, not always what ought to have happened.

Chapter 6 begins “so the word of God spread…” one of the things about the structure of the book is what we have in the book of Acts is an arrangment of panels of material with little linking summary statements – like this one in Acts. Acts is not presented in strict chronological order – there’s a broadly chronological order, but sometimes Luke wants to give background flashbacks to help follow through a theme in the narrative. There’s finess in what Luke is doing. He is operating like Roman historians who tell the chronological sequential narratives about different regions in different literary units. We have some of that in the book of Acts.

Luke is wanting to talk about the geographical spread of the gospel from Jerusalem to Rome. This is historiography, not biography. It’s not just about Peter or Paul – in fact, after Acts 15 we don’t hear about Peter again. It’s not a biography of Paul and it ends on an unfinished note. There’s no story about the death, or martyrdom, of Paul. This is not bios but a historical monograph.

Luke isn’t interested in the Acts of the Apostles but the Acts of the Holy Spirit – how the work of the gospel is fulfilled throughout the world.

There’s lots we’d like to know that Luke is not telling us. Don’t eisegete. We need to be comfortable with the limitations of the text. We can’t bring our own interests into the text. We have to let Luke be Luke. Ancient historiographers were not as hung up about chronology as we are. They didn’t measure time like we do. They were less concerned about precise chronology and happier with general accounts, we can’t impose our precision on their accounts. Ultimately the text as received is what God has decided to give us. It’s important that we leave dogma at the door.

The phrase “The Word of God” refers to the oral proclamation – not some document, in a culture where less than 20% of people could read the primary method of receiving the good news was through oral proclamation of the good news. That’s what the phrase must mean throughout the book of Acts (not the Hebrew bible, not any written documents).

We live in a culture of texts as “literate” people. They weren’t. Most ancient people preferred the oral word to the written word. Consulting with living voices and eyewitnesses was culturally preferential to reading written accounts. Written documents had very limited functions in antiquity. They were not for everybody.

This is a massive work by ancient standards – Luke contains the limit in letter count that you could get on one piece of papyrus. Luke was pushing the envelope in terms of content, Acts makes use of the space on a papyrus in a similar way. Ben thinks Theophilus was Luke’s patron. A real person, not a general title for “lovers of God”…

On the Stoning of Stephen…

Stephen is a Greek speaking Jew, speaking in the synagogue of the freedmen. Stephen is meant to be a deacon, looking after the practical needs of the church, and here he is preaching.

There are a lot of parallels between how Luke tells the story of the death of Jesus and how he tells the story of the death of Stephen. In essence Stephen models Christ’s death. Luke is using a historiographical tool to use history to teach morality. He’s encouraging Christians to follow the model of Isaiah’s suffering servant – and providing a biblical framework for Christian martyrdom – “father forgive them”…

The “Acts of the Apostles” is a misnomer – it’s not anthropological or biographical but theological – and this informs its approach to history. We hardly see any of the apostles except for Peter and Paul.

Luke sees himself as writing in the tradition of Jewish historiographers – like the Maccabees and OT writers.

There’s false witness in both accounts, born out in the Sanhedrin. Jesus should have been stoned (if not for the passover festival). Because there were probably 400,000 people in the city at the time the Jews wanted to make sure that it was the Romans who killed Jesus so that no Jews could say that the problem was of Jewish origin. In the case of Stephen it’s the Jews who carry out the killing. Romans reserved the right of capital punishment in their own hands. The Jews had no legal right to engage in vigilante justice. Their only recourse to capital punishment (legally) was the violation of the Holy of Holies in the temple.

The Romans would never execute a Jew on the charge of Jewish blasphemy. Jesus was executed on a charge of treason, claiming to be a king. Stephen was stoned for blasphemy.

The account of the stoning of Stephen is the longest narrative in Acts and contains the longest speech – it was obviously important to Luke. Luke is dealing with an explanation of how Christianity and Judaism have split. He’s explaining the origins of this split. The ending of the life of a pious Jew, Stephen, and the emergence of Saul/Paul as a force for the gentile mission is a pivotal moment in this movement.

One of the repeated themes of Acts is “father forgive them because they are ignorant”… this comes up in Peter’s sermon “you crucified Jesus because you were ignorant”… Luke doesn’t want to write off Jews, he wants to show that they are not forsaken but that they are in a position where they have rejected Jesus.

In the speech of Stephen we see a retelling of sacred history – from Abraham on, recounting the sad story of the unfaithfulness of the Jews to the work, word, and messengers of God. It’s a repeated pattern in Israelite history, all the way down to Jesus. The Sanhedrin aren’t thrilled with this reinterpretation of their history – in their mind they are good evangelical, bible believing, Jews. This was the ultimate insult. And it resulted in the death of Stephen.

The end of Stephen’s speech is not recorded – the speech (like many times in Acts, eg Paul in Athens) goes on until it is interrupted – and at that point the speech cuts off and is replaced by narrative. This is what happens here. Stephen is in full swing, condemning the Sanhedrin – who become teeth gnashingly furious. It’s when Stephen calls Jesus the “Son of Man” (the only use of the title in Acts) that they rush him and kill him (which is where he cries out “do not hold this sin against them”).

Paul’s “persecution of the church unto death” is the sin he constantly dwells on when describing his pre-Christian life. In Philippians he calls himself “blameless under the law” – nobody could accuse Saul/Paul of being a lawbreaker. But he kept the letter of the law while missing the spirit of the law. He makes this point and then acknowledges that he is the “least of the apostles because he persecuted the church unto death.”

This is how Luke introduces the story of Saul/Paul.

On Paul

Iconography – icons were not intended to be photos but representations of the character of the person. Big heads were not symbols of knowing lots, but of being wise. Descriptions in ancient texts functioned in the same way – they’re not so much about what the people looked like (which was not an issue for ancient writers) but descriptions linked with character.

Who is Paul: he’s responsible for over a third of the New Testament.

Paul the teacher (Acts 11:26)

Paul the prophet (Acts 13:9-11)

Paul the apostle (Acts 14:4, 14, Galatians 1:1, 2 Corinthians 8:23)

Ben reiterates that “The Acts of the Apostles” is a silly name for the book that Luke would have been bemused by. The inspired part of Acts begins with verse one, not with the late addition of the title.

On Barnabas (Paul’s missionary buddy)

Originally Joseph, Barnabas, the name, means “son of prayer” or “son of encouragement”… he’s a Levite convert from Cyprus, part of the 70 select disciples of Jesus, he sold his land to help the poor, held to have been stoned in 60AD.

On Paul again

If we met Paul today, quite a lot of us would probably find him difficult to get on with.

Paul’s Roman citizenship is a trump card that he trots out to save his life. He doesn’t mention, directly, in his letters that he was a citizen. It’s Luke who mentions that.

Paul was probably amazingly fit – his missionary journeys required long treks through harsh terrain. Some of the geography he had to cross in short periods of time were pretty incredibly hostile. To walk from Perga to Pisidian Antioch (like Paul did) requires 600 miles of walking over some pretty massive hills.

When you start seeing the proportions of what’s going on you see that being called to be the “apostle to the Gentiles” is like being told you’re the apostle to the whole world except Israel.

On Paul’s Conversion

There are three accounts of Paul’s conversion in Acts (ch 9, 22, 26) – they are widely separate. The first is in the third person, told about Paul. The second and third are in the first person. Paul himself is reporting the story. In both cases he tells the story in a rhetorically effective way depending on his audience. Paul is speaking to the crowd in the temple precinct (ch 22) and King Agrippa and Roman officials (ch 26).

The first account is Luke’s account of Paul’s conversion. Luke wasn’t there. So where did he get it from? Luke 1:1-4 – he consulted with the eyewitnesses. In this case he must have received it from Paul, his companion from the second and third missionary journeys recorded in Acts.

Acts 9 is straightforward narrative. One of the things Ben wants to dispel is that Paul’s name doesn’t occur as a result of the conversion but when he runs into Sergius Paulus (who has an inscription in Galatia) that he changes his name.

The Greek form of the name Saul, σαυλος meant “to walk like a prostitute” in Greek. Which isn’t likely to work in the work of his missionary context. παυλος in Greek just meant “a short person.” The name change comes because of his missionary work in the gentile world, not because of his conversion. That’s a myth.

Luke, in composing Acts, knows, when he writes what he writes, that he doesn’t have to tell the story on the first go – because he’s going to come around to it again later in the piece. The provision of more detail is a rhetorically effective account – not a contradiction. It’s an elaboration to keep the narrative retelling fresh on the second and third iterations. The mechanism of the encounter – the voice of Jesus speaking to Saul – is the same in each account. Verbatim.

Saul’s experience on the road to Damascus makes it clear that when you persecute the church you are persecuting Jesus, and that his salvation was not through keeping the law – but through grace.

What is the change that happens in Paul’s life? What is the process that we’re talking about? Does he go from being a Jew to being a Gentile? No. Does he go from a person who believes in the Hebrew scriptures to one who doesn’t? No. What happens is that he goes from being an opponent to a proponent of Jesus as a messianic fulfillment. This is not a new religion. But the fulfillment of the Abrahamic promise of blessing to the nations. We can not forget that we have been grafted in to Israel through the work of faithful Jewish missionaries.

Paul doesn’t ever call us Christians – but talks about us being “in Christ” – has that ever struck you as odd as a description of the people of God? This is not a mere metaphor. We are being told that Christ is present everywhere at once. He is the atmosphere in which we live. When Paul wanted to describe who we are, he said we are “Jew and Gentile” in Christ. In Romans 9-11 he goes on a rampage rebuking the Christians for thinking they had supplanted the Jews.

He says: “I would be willing to be cut off from Christ permanently if my people could be reconciled and brought back in” – which one of you would willingly give up your salvation to save others…

and then (paraphrasing)…

“You Gentiles are the wild olive branches that have been grafted in” so you have no basis for being arrogant.

The truth then, and the truth now, is that many Jews don’t believe in Jesus because of the church. Not because of Jesus.

This conversion story has a call that comes with a commission. Paul was not just called to be a follower of Jesus but commissioned to be part of the ministry of the body of Christ. This is true for everybody. Paul and Peter’s missions were not geographically exclusive. It wasn’t a turf war. Paul, Peter, and Apollos were all part of the same team ministering in the same cities.

There’s not always a crisis point that leads to conversion. Sometimes it’s a process that takes time. Your conversion does not need to replicate what happened to Saul. It’s like labour – some are short, some are long, some are painful – in the end a new creature is born. There are a variety of patterns of conversion in Acts. It’s a mistake to schematise what our God personalises.

The eyes have it: sight as the thorn in Paul’s flesh

Galatians (Paul’s earliest work) 4:12-15: “I plead with you, brothers, become like me, for I became like you. You have done me no wrong. 13As you know, it was because of an illness that I first preached the gospel to you. 14Even though my illness was a trial to you, you did not treat me with contempt or scorn. Instead, you welcomed me as if I were an angel of God, as if I were Christ Jesus himself. 15What has happened to all your joy? I can testify that, if you could have done so, you would have torn out your eyes and given them to me.”

What is this about? Ben thinks Paul had ongoing eye problems. When you have a vision you’re supposed to report what you saw, and Paul, on the Damascus “heard” the Lord Jesus. “See with what large letters I write my name” why did Paul write in large letters and need a scribe? What was the stake in his flesh? A physical problem that was chronic but did not effect his ministry. In the ancient world the eyes were seen as the windows to the soul – bad eyes meant a bad soul. Ancient peoples didn’t believe that the eyes were a receptacle of light but the things through which the soul projected…

Paul says, when I came to you you did not condemn me, and did not spit (which was the appropriate cultural response to the “evil eye”… the Galatians didn’t judge Paul on that basis.

Why did Paul need a personal physician on his missionary journeys? Because he had a condition that was not fatal but needed treatment all the time.

Why did the Corinthians say his letters were powerful but his presence weak? He had an ethos problem – his eyes. They weren’t impressed with his appearance. But his words were powerful.

The Roman soldier who was first up the wall was given incredible honour – when Paul escapes persecution via the basket lowered down a wall he claims to have been “first down the wall” an inverted version of Roman honour.

The early letters of Paul are not the early thoughts of Paul – they’re letters from the experienced Paul. Years after his conversion. It seems that Paul laboured in the vineyard for many years before seeing any results.

Ben draws a parallel between Jacob and his post wrestle itch (from Genesis) and the purpose it served as a reminder – and Paul’s continued malady. This doesn’t mesh with prosperity/health gospels – and many prominent and influential Christian ministers and thinkers have died of diseases or suffered chronic ill health. We can’t link prosperity and faith.

Closing points (of sorts)

Luke’s lithmus test for salvation is the Spirit – there is no Christian without the Holy Spirit – we can only tell if someone has the Spirit or not by their words and conduct. Water baptism does not save (or do anything).

Tongues (angelic language) are a legitimate and biblical gift (not found in Acts 2 – but mentioned later).

The Holy Spirit’s job is to convict, convince, convert. It will always point people towards Jesus.

Our gifts are for the benefits of others. The fruit of the Spirit is for the nourishing of the body. There is one fruit of the Spirit – not many. In the Greek. These fruits are meant to be present in all Christians. The fruit of the spirit is about character renovation, the gifts are about ministry. There’s not a necessary link between gifts and maturity. Gifts should be exercised by the mature. If you can’t speak the truth in love you need to stop speaking it. Your character is more important than your gifting. Christianity is more often caught than taught.

“The most important ministry you can have is not the songs (etc) that come from your mouth but the fruits that come from your life.”

The Spirit in the Book of Acts, above all other things, is the spirit of mission and evangelism. All the other achievements of the Spirit (eg healing) are peripheral to that mission.

How to vote

There’s an election coming up you know… but that pales in significance to an election currently occuring at SydneyAnglicans whereby you can place your vote for your favourite church song.

I should point out that there’s only one evangelical song on the list written by an Australian (well, a pair of Australians) and it’s currently in the lead. You should totally be parochial about these things.

Simone has been subtle – but I think a little bit of overt campaigning is called for – if you don’t vote for Never Alone you’re setting Australian evangelical songwriting back by up to ten years.

Dry idea: atheists being “de-baptised” with a hairdryer

This is just silly. A bunch of atheists at a convention decide to have a little fun and “debaptise” themselves with a hairdryer and the Internet just about breaks. A bunch of fencesitters agnostics and Christians have condemned the action as cultic and proof that atheism is a religion (see the comments on this Gizmodo article, or this Neatorama one, here’s the coverage from the Friendly Atheist (and part two)). It’s a joke people. A joke. Thankfully, Fox News is on the job… reporting in an unbiased and completely level headed manner.

Under the headline “U.S Atheists reportedly using hair-dryers to de-baptize” the story’s lede reads:

“American atheists lined up to be “de-baptized” in a ritual using a hair dryer, according to a report Friday on U.S. late-night news program “Nightline.”

Leading atheist Edwin Kagin blasted his fellow non-believers with the hair dryer to symbolically dry up the holy water sprinkled on their heads in days past. The styling tool was emblazoned with a label reading “Reason and Truth.””

The guy doing the “debaptising,” Edwin Kagin, is one of the leading lights of the new atheist movement. He likes to call Christian parenting “child abuse”… but this Nightline story has been way overblown.

“Standing at a podium wearing a long brown monk’s robe, Kagin read with the oratorical skill of a preacher from a set of pages in his hand and invited participants to come forward to be de-baptized.

He recited a few mock-Latin syllables, to the audience’s amusement. An assistant produced a large hairdryer, labeled “Reason and Truth,” and handed it to Kagin. The man who’d elected himself to be de-baptized stood before him. Kagin turned on the hairdryer, blowing the hot air in his face in an attempt to symbolically dry up his baptismal waters.

“Come forward now and receive the spirit of hot air that taketh away the stigma and taketh away the remnants of the stain of baptismal water,” Kagin shouts.

Atheists poke fun at baptisms in this ceremony, saying they believe their waving around a hairdryer holds the same level of magical and spiritual powers as does the baptismal ceremony.”

Funnily enough, Kagin’s son is pretty much the “enemy”…

“And then there’s this interesting twist. His own son, Steve Kagin, is a fundamentalist minister in Kansas.

Kagin said that his son claims to have a personal revelation in Jesus Christ. “I am totally unable to say that’s not true,” he said. “There are examples all through history of quite sane people who have had such experiences. I don’t think it is but I’m not going to say it isn’t.””

This is a bit of a beat up. And it’s giving a little piece of attention seeking way more attention than it deserves.

This (the Devil) is why you’re fat… Part One

You’ve seen the imagery – and now it’s time for the substance. If you’re carrying a few extra kilos (and trust me, I can relate) then this book should spur you on to greater physical fitness. Because we all know that when it comes to God’s love it’s not what’s inside that counts – it’s how good you look.

Chapter One of “Help Lord – The Devil Wants Me Fat: a spiritual approach to a trim and attractive body” is entitled “The Satanic Food Conspiracy!”…

Let me quote to you from the opening paragraphs.

“I don’t see how a really fat person can be a true Christian!”

Normally I ignore such remarks. We all know that being fat or skinny has nothing to do with being saved. But the brother making the statement was so sincere, I thought I’d better hear him out.

“Oh, I replied, “How come?”

See what he’s done here. He’s disassociated himself from the heresy but then given it credence, and indeed, produce a whole book on the basis that you need to be skinny.

“Well, in Philippians 3:19, the apostle Paul speaks of those whose god is their belly. When a person is overweight it seems to me that food is his real master, not the Lord Jesus. Those extra pounds are proof he puts his stomach ahead of the Lord.”

This prompted some soul searching. Our author used to be “large.”

“Then I looked down at the rolls around my waistline. One thing was obvious – I was eating more food than I needed… Is it possible the Devil was using food to weaken the Lord’s rule over my life? Ugh, I didn’t like that idea. Probably because the answer I was getting back was a “yes.”

From what I knew of the devil, food was something he would definitely use. He’s skillful in turning good things to evil purposes… we could consider sex. Here is a beautiful thing God has given us, a drive of the organism to remind us how incomplete we are in ourselves. Just as we need a mate to make us complete in the flesh, so do we need the Lord Jesus to be complete in the Spirit… If Satan has the ability to turn God given drives and turn them to evil, why would he ignore something as vital as eating.”

Here’s the clincher for his argument (and if you read this conclusion with his sex analogy in mind you can understand why he thinks a glass of water is a satisfying start to the day).

“When we’re eating, do we think in terms of what our bodies need? No, we think of how good it tastes or how satisfying it is to stuff ourselves. That’s got to be the work of Satan. He gets us to shift our focus from eating what we NEED to eating what we WANT… Beyond that there seems to be a FOOD CONSPIRACY in our land. Fast food stands are springing up like gas stations. Household magazines are filled with colour photos of delicious pastries and desserts. Everywhere you look it’s food-food-FOOD…

“Most Christians seem to think it [their body] belongs to them; that they can do with it as they please. As a result they pollute it and defile it. We’re familiar with the usual things that defile the body: drugs, alcohol, tobacco and sex sins… But most subtle is the way the devil gets us to defile our bodies with food. Many who profess to put Christ first in their lives, deny His lordship with a knife and fork.”

No doubt Keller would enjoy this bit…

“Thus we have Christians who wouldn’t think of lying or stealing or committing adultery, unashamedly going around with bulging bellies. By this they are announcing to the world, “I’ve got another god in my life!” This is in direct violation of the First Commandment.”

The problem though, is Television. If this book were written today the problem would no doubt be all the food ads – but back in 1982 it was the breaks for “station identification”… this was an opportunity to get up to mischief.

“You’re watching TV. There’s a break for station identification. Do you just sit there? No. You ease out of your chair and head for the kitchen. The refrigerator door swings open. You peer inside. Are you hungry? No. does your body need food right now? No. Do you know why you’re standing there staring like that? No…

If nothing is available from the refrigerator you may open a cupboard or two. Some more staring. If you spy something that can be eaten conveniently, you reach for it. If not, you close the door… “I don’t need it anyway” but that’s a victory of the moment. You’ll be back shortly. You win sometimes and you lose sometimes, but the final score is totaled up on the bathroom scale. If you’ve gained weight you are clearly losing the war.”

If you haven’t been offended by this pastoral method before, you probably will be now…

“The devil doesn’t care about fat. He’s concerned with what happens to Christians when they’re fat… in spite of the common notion that fat people are more jolly, the real truth is they’re often more lonely. They make good pals, but not sweethearts. As a result, fat people do a lot of pretending.”

Basically, if you know a happy fat person they’re just faking it. And Satan spends his time helping them weave a fantasy web of self-satisfied delusion…

Except, of course, for those who are fat because of glandular conditions. There’s a disclaimer at the end of this chapter. I would have put this at the front personally… the disclaimer points out that fewer than 1% of the population have this problem and that these people are not the target of this book.

Here are the reasons Satan wants us fat.

- Despair – How many overweight Christians cry out to the Lord for victory over food? Until a Christian dedicates his stomach to the Lord he can pray all he wants and nothing will happen. The body is the Lord’s. And the relationship between the body and the spirit is so close that the power of the Holy Spirit in one’s life DEPENDS ON THE YIELDING OF THE BODY TO CHRIST. Frequently the greatest barrier to surrender of the body is the STOMACH. Until it is surrendered, the person can pray until he is blue in the face and there’ll be no answer. He prays in disappointment. When his disappointment becomes despair the devil has acquired a destructive emotion to use against him.

- Foothold – What Satan really seeks is a foothold on our WILLS… when we take ONE BITE of food more than we need, it provides him with a chink in our armour… When he can get us to eat more than we need – at his suggestion – he has gained the foothold he wants. That is why a few extra pounds is such a serious matter. They become an unanswerable proof of his dominion.

- Enslavement – This is what the devil is finally after. He doesn’t want us in control of our flesh. He wants us SLAVES of our flesh. Why? The flesh is his territory.

Lest you be thinking that this issue is simply limited to your own stomach (and no doubt gluttony does lead to being overweight, as do other factors like poor nutritional education… and the types of processed foods that are part of modern diets…)…

“As far as I can determine we are in those days of “eating and drinking” of which the Lord spoke (Matt 24:37-39). It is one of the signs of the last days.”

The chapter finishes by assuring us that being overweight is just as bad as being an adulterous pastor…

“Some years ago a well known evangelist on the West Coast was shot and killed in a motel room by an enraged husband. The preacher was caught in bed with the man’s wife… But let me ask this: “is it any worse for the Lord to find you in bed with someone else’s wife or husband? Or to have him find you 20-50 pounds overweight?

The Devil made me eat it…

I thought I’d share with you some tidbits from the newest edition/addition in my library. These are photos from my iPhone.

It’s brilliant. It opens with a statement I can paraphrase as: if you/r friend are/is overweight, not only is it the devil’s fault but you should question your salvation.

I’ll deal with the substance of the argument in a future post – but now I’m going to share with you some of what I think makes this book special – its style.

Some of its illustrations look like Chance cards from Monopoly:

With a bit of high art (which may suggest that the original sin was gluttony not disobedience).

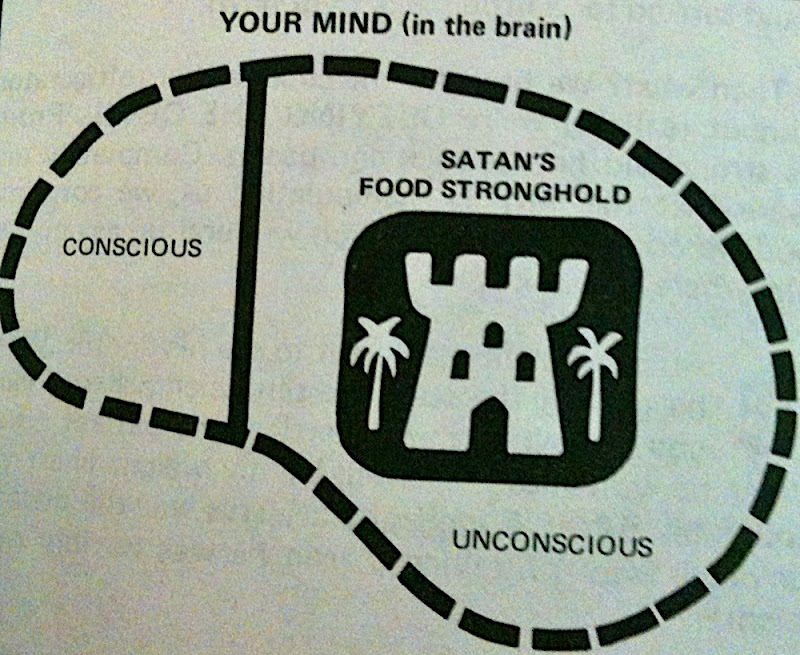

The problem is your sub-conscious. It’s the Devil’s playground.

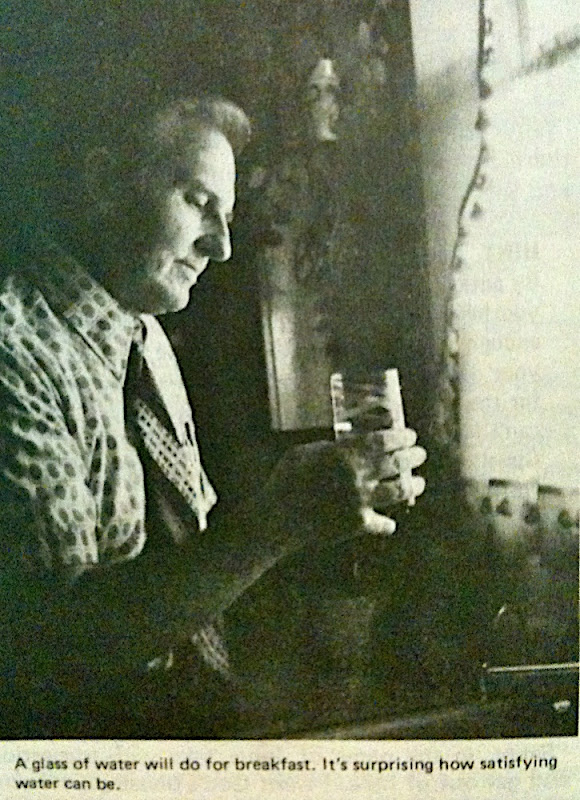

It’s this sort of advice that will set you on the path to skinniness:

It says: “A glass of water will do you for breakfast. It’s surprising how satisfying a glass of water can be.”

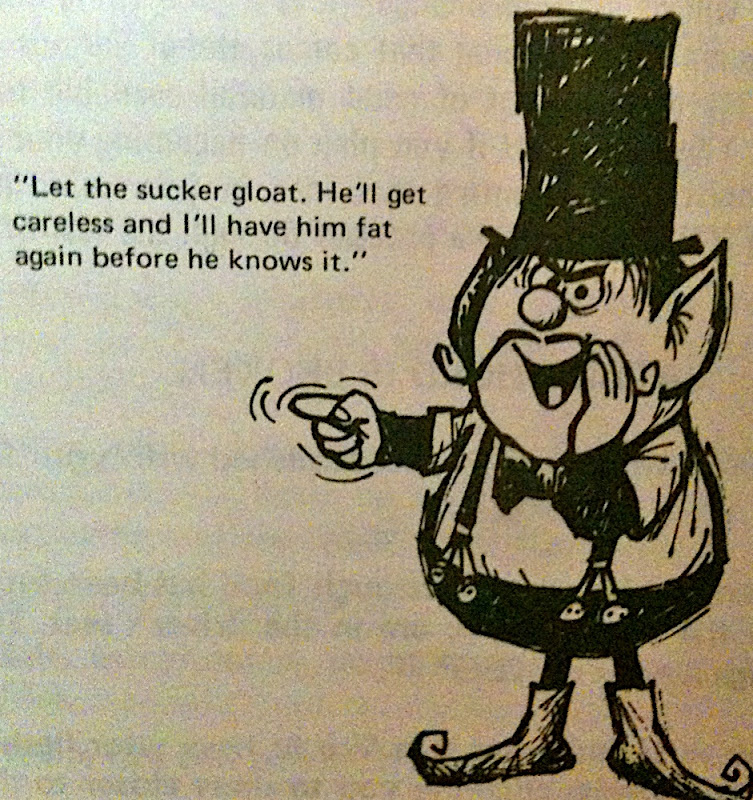

The Devil is an imp in a top hat.

He ends up in web of positive thinking and healthy eating advice:

I’ve only posted less than half the post-worthy illustrations here (and they’re photos from my iPhone). I’m hoping to post the rest in coming days/weeks in better quality and with the kind of analysis you’ve come to expect from St. Eutychus.

I trust you’ll enjoy this journey of self discovery thoroughly.

Listen up nerds. Westboro Baptist says God hates you

Everybody’s least favourite protest church is getting contempervant. First up, they’re targeting a comic convention. Because God apparently hates nerds, and super heroes are idols.

Picture credit: Kotaku’s coverage

“It is time to put away the silly vanities and turn to God like you mean it. The destruction of this nation is imminent – so start calling on Batman and Superman now, see if they can pull you from the mess that you have created with all your silly idolatry.”

The proof text on that sign, Romans 9:13, is a little bit odd. Apparently Esau was a nerd.

“Just as it is written: “Jacob I loved, but Esau I hated.”

This just shows a bizarre disregard for any description of Jacob (a mummy’s boy) and Esau from the Bible (Genesis 25).

Here’s a description of the two from Genesis:

“27 The boys grew up, and Esau became a skillful hunter, a man of the open country, while Jacob was a quiet man, staying among the tents. 28 Isaac, who had a taste for wild game, loved Esau, but Rebekah loved Jacob.”

Esau is an anti-nerd. It seems more likely that God loves nerds who stay at home quietly with their mothers. I’d go a step further and suggest that the Westboro Baptist crew, in their militant and confrontational approach to spreading the gospel, have embrace an Esau like approach to life. And thus they are damned by their own proof text.

I sent Westboro a letter to let them know. I’d hate for them to fall foul of accusations that they don’t know their Bibles very well…

“Hi guys,

I noticed your protest of the Comic Convention featured a sign “God Hates Nerds” citing Romans 9:13 as a text.

Romans 9:13 “Jacob I loved, Esau I hated” doesn’t really work when applied to nerds.

Esau was the least nerdy of the pair – in fact, Genesis’ description of the brothers (25:27-28) suggests that it was, in fact, Jacob who was the nerd. Jacob stays at home with mum (typical nerd behaviour) while Esau goes outside and hunts like a man.

“27 And the boys grew: and Esau was a cunning hunter, a man of the field; and Jacob was a plain man, dwelling in tents.

28 And Isaac loved Esau, because he did eat of his venison: but Rebekah loved Jacob.”

If you’re going to use scripture to back up your arguments at least do it properly.

Regards,

Nathan Campbell”

Other events that Westboro Baptist will be protesting in the near future include a Baseball game (God hates sport), and a Lady Gaga concert (God hates gender ambiguous costumed pop stars).

There schedule comes complete with this little parody of Hallelujah, perhaps Westboro’s attempt at contextualisation:

“Your God has seen what you have done. There’s nothing new beneath the sun. He’s sent a lying spirit down to fool you. We’ve seen your flags on your crumbling arch. Your filth is not a victory march. God hates your feasts and faithless Hallelujahs.”

On Gaga…

“Now what type of wicked hypocrites would we be if we did not warn this little false prophetess and all of her over-indulged sycophants that they are each one, individually heading straight to hell in a gender-confused, self-loathing, tone-deaf hand basket and that a gift from the God they hate?”

Thanks to my friend Mika for the tip.

Five steps to better coffee

This Saturday night our church is hosting a coffee night with myself and former Di Bella Coffee Roaster Daniel Russell. Here’s the flier. You’re more than welcome to come along – RSVP in the comments.

I’m about to post five posts in a series “five steps to better coffee” which will become the booklet we give out on the night (hopefully). I’ll also do a bit of a dummies guide to home roasting.

If your church (in Brisbane) would like to run a similar night – let me know. I’m sure Dan and I can be talked into helping out…

Bruce Winter’s tips for apologetics

We’re doing a bit of a mini-subject on apologetics this semester as part of a weekly “preparations for ministry” session.

Yesterday’s session featured Bruce Winter sharing some insights on the important discipline of apologetics garnered from his extensive studies on Paul and his culture, and from his experience as an apologist in Singapore and while working as an academic in England (Cambridge).

Here are my notes:

Every Christian is required to be ready to give a reason to the hope that lies within them.

It’s interesting that the word there – apologia – goes beyond the idea of giving some answer. Stoic philosophers used apologia to argue their case while interacting in a substantial way with the mindset of the people they’re addressing.

How are we going to engage in apologia with people in the 21st century? Two Ways To Live isn’t going to work for everybody. We see from the way that Paul tackles apologetics that he engages the culture around him.

We need to engage the audience and move around their world – Paul’s letter to the Romans is a great apologia that removes objections to the gospel – objections that come from the mindset of people living in first century Rome.

Paul argues that we need to pull down every argument against God both within and outside the church – he talks about demolishing the stronghold of people’s ideas contrary to God, he distinguishes between the argument and the person. Paul demolishes and reconstructs these arguments “captive to Christ.

Acts 17 is a good example, and a good paradigm, of Paul connecting with the audience and their expectations and producing converts. This is the parliament of Athens.

Five things to learn from Paul to connect and engage with people’s world. This message needs to engage the thought world of the people around it.

- We have to connect our message with the audience we’re speaking to – Paul connects – he makes the connections the audience required (in introducing a new God to the council – eg the building of a temple, holy days/sacrifices), he also uses their culture (eg the statue of the unknown god) to engage.

- We have to structure our message in a way that provides a hearing for the gospel – The framework we present the gospel in changes based on the audience – talking to sciency people requires a different presentation to talking to people from different religious backgrounds. The main aim is that people hear the gospel connected to their world.

- Know how to connect the message, and know what it needs to correct – Paul knows that people need the gospel, but he also knows what the objections to it are, and he addresses them with the correction of the gospel.

- Converse with their world – it’s remarkable when you read historical sources talking about the nature of God and compare it to the way Paul quotes their arguments and poets/philosophers in his apologia. He understands their world, their language, and their issues. Paul is even able to point out inconsistencies in their current thinking and actions (they talk about the nature of Gods not living in temples made by man, but visit temples – Paul points out they aren’t living up to their basic beliefs and teachings.) He’s read the literature. He knows their teaching. He is well able to bring them to that point through the quotations of their poets.

- He confronts his audience – Paul doesn’t steer clear of the topic of God’s judgment and the predicament that places his audience in. God’s judgment coupled with God’s amnesty (he calls on all people, everywhere, to repent). Paul doesn’t compromise. He’s not prepared to negotiate on the fixed points that his audience was bound to be opposed to. It’s a different worldview. Paul’s sermon in Acts 17 converts people from those opposing points of view and philosophy.

Some questions to ask regarding our approach:

- How are we going to talk to different audiences?

- How do we talk to those dealing with the certain uncertainty of death?

- How do we connect with their views and preconceptions about Christianity and the world?

- How can we talk to them about their world?

- How do we talk to affluent people who think they have everything? Their question is different – “what’s missing?” – “what is it?” How do we raise the issue of the gospel in a way that articulates this need in a way they might never have considered?

A question to prompt thought in others is: If you had your life over again how would you do things differently? Everybody is fundamentally aware that they do the wrong thing at least occasionally.

We’re not dealing with blanks slates but people who have spent their lives deliberately ignoring (and justifying ignoring) general revelation. Romans 2 suggests that it’s our conscience that judges us as we face God at judgment day – so the question “how can God…” is irrelevant.

Exegeting our suburb: trying to understand the area around our church

I gave a sermon a couple of weeks ago at Clayfield. On Matthew 9:35-10:22. A passage where Jesus describes the work of evangelism as a plentiful harvest with too few workers. I won’t bore you with the exposition I did of the passage, suffice to say my big idea was that we are to be part of the harvest in whatever way we are able because it is urgent. I spent some time showing that Jesus’ commission to his disciples to preach the coming kingdom of God to Israel was a specific commission which is replaced at the end of the book with the “great commission”…

My application focused on the area of Clayfield as our church’s mission field. It was a “think global, act local” slant. Here’s roughly the third quarter of my sermon, where I got some stats on Clayfield from Queensland’s Office of Economic and Statistical Research, I got some other bits and pieces from the Real Estate Institute of Queensland, and a little bit from OurBrisbane.com. I don’t completely buy into social demographics as a key for understanding people in a suburb. I like Tourism Queensland’s market segmentation approach a bit better – they split people into interest groups rather than arbitrary groups based on socio-economic factors. While the approach has weaknesses it’s also a really easy way to gain some insights into a community beyond the “people I know who live here” approach. And some generalisations are good generalisations.

Clayfield is a pretty difficult suburb to figure out, other than a local primary school that acts a bit like a hub, there’s not much sense of community. I preached this sermon (with different stats) in Townsville last year, and it was heaps easier to read Townsville’s pulse (possibly because that was also my job).

Here’s part of my application, copied and pasted from my manuscript, it includes some stats on Clayfield, seven basic tips on reaching Clayfield (or any community) from those stats, and of course from the passage itself:

While we can’t just take this passage and apply it completely to ourselves – we shouldn’t expect to be healing the sick and we shouldn’t just preach to the Jews – we can look at this passage and see Jesus’ concern for the lost – his desire for the good news to be preached. And that should be our priority as a church – and Clayfield is our mission field. I know many of us travel across the city to be here each Sunday, and the idea of Clayfield being our mission field may sound foreign – but if we’re not thinking about how we, as a church, can reach the suburb around us… then who will be?

It’s our job as Clayfield’s “local church” to be reaching the community with the good news of Jesus. For us the great commission extends to where we live, where we work, and where we play – but it also has to be where our church family is.

The great commission is a pretty clear imperative for Christians to be taking the gospel to the ends of the earth. We need to be people who think globally, but act locally. If we don’t reach Clayfield – then who will? Lets talk a bit about Clayfield. Our harvest.

Have you ever thought about Clayfield as a mission field? It’s hard. It’s very hard. Finding a community pulse to tap into, to be a part of, is difficult. Figuring out the wants and needs of the average Clayfielder is hard. We know, don’t we, that this is a suburb, or district, crying out for the gospel. But how do we help our neighbours know it too?

Here are some of the facts about Clayfield.

We’re not an area of social disadvantage – one in fifty Clayfielders are in the bottom economic band, While one in three people are in the top band. We’re a prosperous lot, most of us have who want jobs have jobs, half of the residents of Clayfield own, or are paying off their home. Sixty percent of us have post-school qualifications.

This presents a challenge for us as we present the good news of a crucified messiah.

It’s a caring community – one in ten residents work in health or some sort of social assistance area, one in five volunteer their time for a community group.

- Help Andrew and Simone with RE and building relationships at Eagle Junction school, find someway to help out at Clayfield college. Fifty percent of school students in Clayfield attend public schools – bastions of secular culture, with the other fifty percent attending church run private schools around the city. When you look at just primary school attendance a much bigger percentage are in public schools. RE is a great opportunity to get the gospel in front of non-Christian kids, and to encourage our kids to be passionate about sharing the gospel with their friends.

- Volunteer for a community organisation – I know we’re always up here asking for people to volunteer for things at church, but we can’t spend all our energy on serving each other and forgetting the world around us. Almost one in five Clayfield residents volunteer for some organisation in some capacity. If you’ve got kids who play sport, help out with their team, bring the oranges, help the coach at training. Put in the effort to go to matches and chat to the other parents. You’re probably doing this already – and you may even be doing it with gospel intentions – but that’s the key to harvesting.

- If you live in Clayfield, talk to your neighbours, invite them to our Local Knowledge events coming up – they’re a great intro to people from church, they’re designed to be non-threatening. Try to get your neighbours darkening the doors of church and meeting this family that you’re a part of.

- Shop locally – there are 5,400 businesses operating in the Clayfield electorate. Talk to a shopkeeper. Become a regular. Think about how you can get out there to meet people.

- Use your gifts for the gospel – if challenging conversations and confrontations are not for you then why not look for opportunities to encourage other people in our church family to get involved, if hospitality is your thing why not invite your friends from work around for dinner with some friends from church. Gospel ministry is a team game. We see that in the way people show hospitality to the workers in

- Pray for harvesters – you’ll notice that’s what Jesus actually calls his followers to do in chapter nine verse 38, before they get sent out on the road, That’s how we all can play a part. Because, as Jesus reminds the disciples as he speaks to them, God is in control. And all of us, as Christians, can pray.

- Invest in the harvest – if all of this seems beyond you, and even if it isn’t, give generously to the work of the gospel. Harvests on farms need resources. Think about what resources you have that you can contribute to the gospel – maybe it’s your time, maybe it’s your money. The CMS slogan has it right – we’re to pray, give and go.

But if those aren’t your cup of tea there are plenty of other options – if I can drive a tractor on my father-in-law’s farm and a bunch of fishermen and accountants can spread the good news throughout Israel while facing persecution from the Government – preaching a message interpreted by their hearers as stupidity, at least after the cross… think about the non-Christians in your life, your family, your colleagues, your children’s friend’s parents, your doctor, your butcher, your baker, your candlestick maker – think about how you can be part of presenting the gospel to them. If you want to be part of the harvest, if you’re a Christian who wants to see people challenged to live with Jesus as Lord, then don’t delay – the harvest is urgent. Get involved. Find something you can do and get in and do it.