There’s what seems like a coordinated push from hard-right Christian media and social media outlets this week to raise awareness about the dangers of ‘cultural Marxism.’ Here, for example, is a quote from the ACL’s Martyn Iles in his third post linking “Black Lives Matter” to cultural Marxism.

“Black Lives Matter: not what it says on the tin.

It is so important to exercise discernment – a virtue mentioned dozens of times in scripture, essential to living wisely.

There are many labels doing the rounds at present – Black Lives Matter, Safe Schools, Extinction Rebellion, Liberation Theology… and others.

Each of these attractive labels has a surface appeal, but masks what lies within. They are fronts for Cultural Marxism.

The “facts” that lie at their roots are popular deceptions. A supposed underclass of children oppressed by heteronormativity… horrifying, systemic racism by police officers… an imminent ‘end is nigh’ style climate catastrophe… Jesus as a figure concerned mostly about the earthly ‘oppressed’ and mostly for their empowerment in earthly systems.

These deceptions alarm people.

They recruit people’s emotional support for an anti-Christ political cause.”

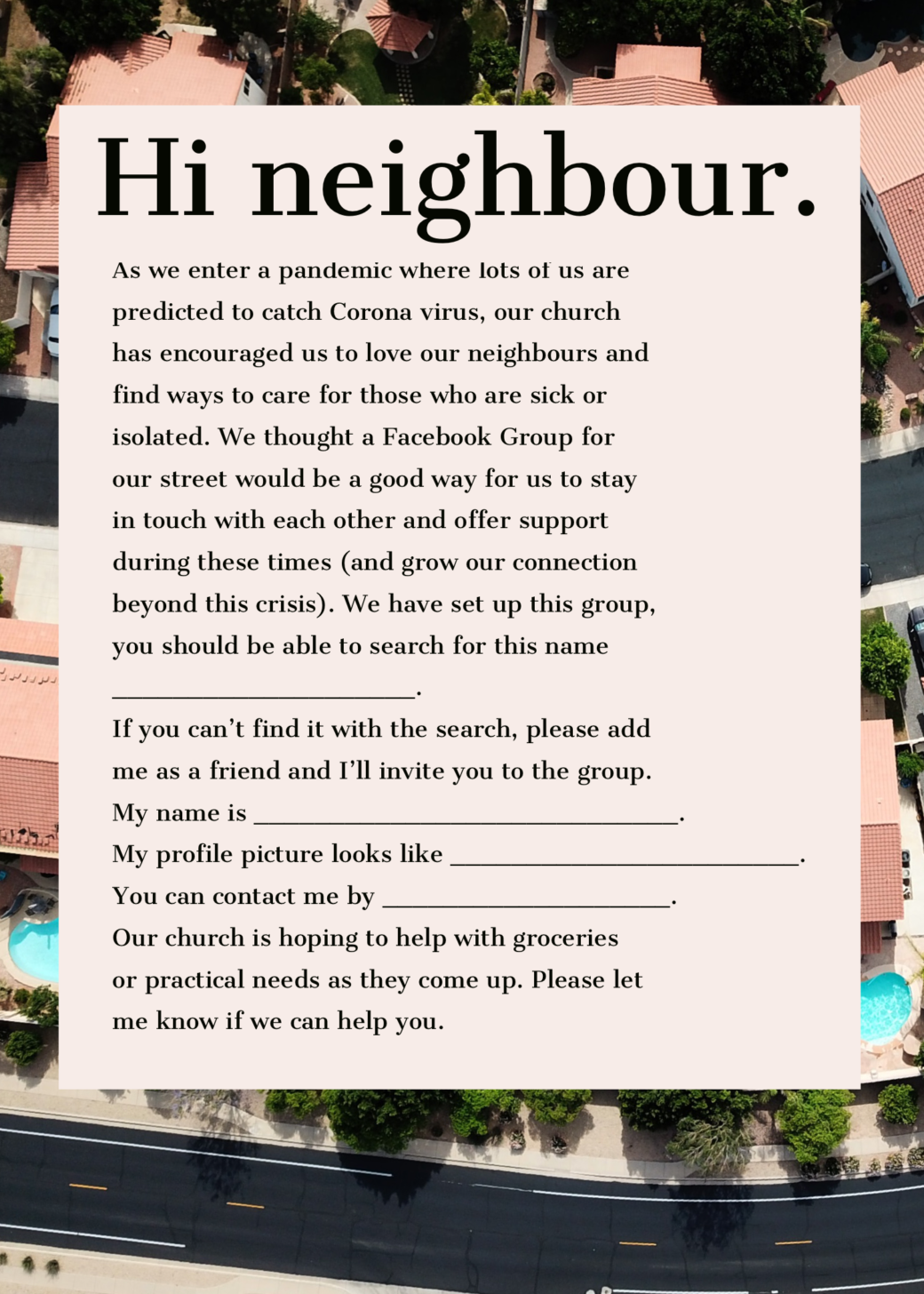

Now. Before I go much further, I think it’s worth making a distinction in our conversations around race issues between Black Lives MatterTM (@blklivesmatter), and “Black lives matter” the statement, and #blacklivesmatter the hashtag. One way to imagine the distinction would look like:

“Because black lives matter that we should rally against systemic racism, and also because #blacklivesmatter, we should ask @blklivesmatter to reconsider its position on abortion.”

This would, as an example, use the phrase to affirm a truth: black lives do matter. Connect the use of that phrase to a conversation on Twitter, where #blacklivesmatter works as a hashtag, and address a concern that one might have with the Black Lives Matter organisation and its vision of the good. One might stand with @blklivesmatter on its diagnosis of the problems in our western society, and the way white privilege works systemically to disenfranchise non-white people, and see how historic injustices like slavery or dispossession continue to work themselves out today (so they’re not really history) without sharing @blklivesmatter’s solutions to the problem.

Others, like my friend David Ould have a principled disagreement (along the lines of avoiding association with evil) that I think is both an example of the sort of prescriptive v descriptive word games I’ve mentioned before, and too much of a concession around terminology (rather than entering a contest) to one party in a conversation. If the meaning of words is contested, rather than fixed, more people are able to enter a conversation, bringing more perspectives and richness to the commons. Objections to participating in the Black Lives Matter cause or conversation tend to, at one level, conflate entity, statement, and hashtag and treat them as a monolithic identity marking thing — and then some, like Iles, jump from that monolith to this idea of “cultural marxism.”

It’s not just Iles who’s on the warpath against “cultural Marxism” — you can find articles in The Spectator from the Presbyterian Church’s very own Mark Powell titled ‘Cultural Marxism’s War On Freedom‘ (and if one was to play Presbyterian assembly bingo you can tick off that box on your sheet just about every time Mark speaks about a social issue), you can follow the dirt sheets at Caldron Pool where, for example, young Ben Davis says “Cultural Marxism is a poison eroding the West from within and we need to know how to identify it,” the definition this piece offers is:

“One of the ways in which relativism has influenced society is through Cultural Marxism, or “Social Justice”. Like Classical Marxism, Cultural Marxism is an inherently divisive ideology. Where Classical Marxism was concerned with class warfare between the wealthy and the working class, Cultural Marxism shifts the focus to imagined conflicts between the privileged oppressive majority and the disadvanced oppressed minorities.

Which category a person falls into is determined by certain aspects of that individual’s identity, such as gender, skin colour, sexual preferences, family, ethnicity, culture, and religion.”

The “Canberra Declaration” an obtuse right-wing Christian thinktank, defines Cultural Marxism as “a secular philosophy that views all of life through the lens of a power struggle between the oppressed and the oppressor,” where:

“The oppressor is usually an aspect of traditional Western society such as the family, capitalism, democracy, or Christianity. The oppressed is anyone who is or who feels marginalised by these institutions, depending on the cultural and political debates of the moment.”

Using word or hashtags (like ‘privilege’ or ‘feminist’ or ‘systemic injustice’ or ‘patriarchy’) — even to acknowledge those as categories — can trigger an avalanche of despair from anti-social justice warriors who want to stamp cultural marxism out of the system; and certainly want to prevent anything like “cultural marxism” slipping into the church; in doing so these political activists end up setting up a boundary marker around the Gospel such that anyone to their left is either a ‘woke panderer,’ or partnering with an anti-Christ, or both. Here’s Iles again:

“I condemn Black Lives Matter because they are a Marxist movement.

Marxism is anti-Christ.

They substitute sin with power.

They substitute the individual with the tribe, imputing guilt, innocence, and judgement to collective groups, not responsible people.

They absolve guilt, not by repentance, but by claiming victim status. Sin is justified for some tribes.

They do not absolve guilt for all. It cannot be absolved for the wrong tribes.

They exist to agitate, tear down, create chaos, divide, and destroy. That is the cultural Marxist objective – wreck the joint; destroy the system; do it violently.”

“Anti-Christ” is very loaded and evocative terminology in Christian circles; it draws on beastly satanic imagery (and eschatological conspiracies about end times); and it is pretty much the ultimate statement of anathema. Thing is, the Bible is quite careful to describe the term:

“Dear children, this is the last hour; and as you have heard that the antichrist is coming, even now many antichrists have come. This is how we know it is the last hour.They went out from us, but they did not really belong to us. For if they had belonged to us, they would have remained with us; but their going showed that none of them belonged to us.

But you have an anointing from the Holy One, and all of you know the truth.I do not write to you because you do not know the truth, but because you do know it and because no lie comes from the truth. Who is the liar? It is whoever denies that Jesus is the Christ. Such a person is the antichrist—denying the Father and the Son. No one who denies the Son has the Father; whoever acknowledges the Son has the Father also.” — 1 John 2:18-23

Now, this isn’t to say that the Bible doesn’t speak about political systems and structures to condemn them; it does; it tends towards describing those structures as beastly, animalistic, following in the footsteps of that dragon/serpent Satan. Revelation is loaded with this sort of imagery with the finger pointed squarely at worldly power. But more on that below…

What it uses the term ‘antichrist’ for is for those who deny that Jesus is the Christ, those that “deny the Father and the Son,” those who were once part of the people of God, who have “gone out from us” — for John this is probably people returning to Judaism denying that Jesus has been raised from the dead (see this post to flesh this out a bit). To be antichrist is to deny substantial and fundamentally important truths about Jesus; it is not to subscribe to a particular political system, or to use terminology to enter discussion with those subscribed to a particular political system.

But interestingly, each of the figures I mention above — Iles, Powell, and the writers of Caldron Pool — have, in the last 12 months, very carefully and closely aligned themselves with one who fits this bill: a Trinity denying modalist who denies that Jesus, the son, came in the flesh, denying father and son (by saying only the father, named Jesus Christ, exists). Iles in particular did his very best to position this figure as a Christian for the sake of his politics and fundraising, despite being given substantial evidence for this person’s theology.

But back to “Cultural Marxism”…

One of the problems I have with the attack on cultural marxism is that part of the critique is a critique of the idea of systemic sin, built on an argument that there is systemic sin at play in our institutions. What the noise about cultural marxism really boils down to is a feeling amongst a subset of conservatives that they are losing the culture war because they’ve lost control of cultural institutions.

If the so-called left, including the “black lives matter” conversation, is suggesting that systemic racism is a problem, and that part of the problem is with a ‘hegemony’ consisting of white people (typically males) who control political, economic, and cultural institutions, and so set patterns of behaviour in order to hold on to the status quo of wealth and power, at the exclusion and expense of others; and if this is “cultural marxism” — then the so-called right is responding by suggesting a conspiracy where a system of leftists (the cultural marxists) are conducting a long march through the institutions. This leftist system now apparently seeks to deconstruct and reconstruct public belief, behaviour, and discourse. It’s actually “systemic set of sins A” v “systemic set of sins B” — and Christians should have issues siding with either. We have our own kingdom, with our own king.

While I’m happy enough for ‘cultural marxism’ to be a contested descriptor of a certain element of the left, I think it’s dangerous to use it prescriptively, to label and dismiss a group of people (and I’m struck by how often the same people not happy to use Black Lives Matter because of its political association are happy to use “cultural marxism” with no regard to its political associations). I don’t use it as a label or to open up discussions with those on the so-called left because it’s not a description they would typically apply to themselves, and it is a term with troubling origins. Aussie scholar Rob Smith has a long article on Cultural Marxism and its origins as a school of thought in Themelios that concludes:

“Given the existence of conspiratorial explanations of the nature and goals of Cultural Marxism, is there a case for avoiding the term and using an alternative (e.g., neo-Marxism or Critical Theory)? In my view, there is no inherent problem with the label, but Christians ought to be careful with how (and to whom) it is applied. It really can function as a kind of “weaponised narrative” that paints anyone who gets tagged with it as being “beyond the pale of rational discourse.” It can even be a way of dismissing fellow believers who display a concern for justice or environmental issues or who are mildly optimistic about the possibilities of cultural transformation. We should certainly discuss and debate such matters, but Carl Trueman is right: “Bandying terms like ‘cultural Marxist’ … around simply as a way of avoiding real argument is shameful and should have no place in Christian discourse.”

One might then ask if the Caldron Pool, Canberra Declaration, Spectator articles and Martyn Iles’ recent Facebook posts manage to clear the jump of ‘avoiding real argument’ and bandying the term around to create a boogeyman, and dismiss other perspectives from fellow Christians.

I was convinced by Christian friends with some Marxist sympathies (especially because of the Marxist critique of capitalism), that ‘cultural marxism’ is an unhelpful pejorative, or snarl, that shuts down dialogue between Christians, and between Christians and non-Christians on the so-called left, so I don’t use it. I was probably more convinced by an analysis of the phrase “cultural marxism” from the guys at The Eucatastrophe (here’s part 1) than I was by Smith’s take. I do use other ‘contested’ terms in order to open up dialogue with those same groups, and I’m increasingly aware that this closes down dialogue with those on the so-called Christian right, either because my use of terminology makes me a ‘woke panderer’ or because my descriptive use of language (and post-modernism) is an affront to their modernist prescriptivism. I’m yet to be convinced that ‘privilege’ and ‘patriarchy’ aren’t essentially Biblical terms that align with the Biblical picture of sin. That’s an area for me to consider carefully. I do think the dominant Christian voices in my tradition tend to conflate ‘Christian’ and ‘right wing’ in ways that exclude those on the left so my bias is towards including or embracing those who might otherwise feel excluded by default.

If I were ‘code switching’ and speaking to my friends on the Christian right, or just secular conservatives, I’d be acknowledging a particular agenda from the left wrapped up in deconstruction, and cancel culture, and attacks on free speech, religious freedom (in some forms) and occasional attempts to enshrine a particularly gnostic view of sexuality and gender that denies the reality of bodily sex in favour of feelings. I’d acknowledge that there are certain expressions of marxism, and certainly its solutions beyond the toppling of capitalism and oppressive power structures, that are just as evil.

I’d reject the idea that it might be ‘better the devil we know’ and suggest a Christian approach to politics might be one that seeks to obey Jesus, and for Christians to be people of virtue who practice the “golden rule” while taking up our cross rather than our sword. I’d acknowledge that the secular left is unforgiving, and weaponises shame, having watched cancel culture attack a prominent Aussie barista this week, and J.K Rowling. I’d suggest it’s odd that “the left” wants to pit Donald Trump (the big evil) against Martin Luther King (the big good) in this present moment, while ignoring significant evidence that MLK should’ve been “cancelled” because #himtoo. I’d acknowledge that culture wars and politics as a zero sum game are destructive to civility, pluralism, the ability to coexist, democracy as an acknowledgment of the equality of all (rather than the victory of the winners), and ultimately to our ability to love our neighbour.

These figures on the so-called “Christian right” might pretend to be acting neutrally, but by supporting a status quo (especially a capitalist one as opposed to a Marxist one, as though there are only binary options for our economics) are identifying their own version of systemic or structural sin to condemn the identification of structural sin as antichrist.

What might be true of a leftist conspiracy, where a system is developed to fight a culture war could also be just as true of a rightist conspiracy. The right’s antithesis to cultural marxism, where the so called ‘free market,’ and individual autonomy and the right to own property (including, as Locke put it, the idea that an individual person is a property in their own right) is just as systemic. And ultimately the market is actually controlled by a group of people (those who decide the rules of the game and serve as gatekeepers), and the whole game is rigged to benefit people who fit with, and perpetuate, the status quo (we might call these people ‘the privileged,’ and these people might include me). If the left enshrines various ‘identities’ as idols, the right enshrines money, property, and personal autonomy.

There is nothing sub-Biblical about the idea that sin and curse are enshrined in structures that oppress. This is a thoroughly Biblical idea — and it’s a double edged sword. It cuts down the utopian eschatology of both the left, and the idea that we might find heaven on earth if we get rid of some bourgeois class of oppressor and their oppressive structures (especially capitalism), and the right, and the idea that we might find heaven on earth if individuals are free to own and accumulate property and wealth according to their ability (with no acknowledgment of the way this might play out intergenerationally, and that greed might occur and massively distort the market at the expense of those without that same intergenerational cachet). Both ideologies are beastly without Jesus, and neither totally align with the kingdom of God as we see it revealed in Jesus in his death, resurrection, ascension, pouring out of the Spirit, and his eventual return to make all things new.

Christians should not be surprised that sinful people form communities (and political visions) around idols, and that as we do this, our sin becomes enculturated and forms the structures and norms of life together.

This is precisely what idolatry does to the nations around Israel, and precisely what happens to Israel when they become like the nations and choose to worship created things instead of the creator. Our common objects of love — and whether we’re in lefty sub culture or righty sub culture — our common political visions — will form and deform us, and they don’t simply do this internally but as we build societies, cultural artefacts, relationships, and systems to pursue these (idolatrous) visions of the good. To suggest that this sort of system is never built along racial lines is to ignore the testimony of the Old Testament; but these systems are also built along ‘market’ or economic lines too.

The Bible is not neutral about questions of power; specifically about questions of dominion, and the abuse of power where instead of cooperating in spreading God’s dominion over the face of the earth as his image bearing gardeners, we turn to seek domination over one another and enshrine that in nation v nation, or culture v culture contests. Ultimately the Bible pits God’s kingdom as revealed in the crucified, resurrected, exalted, spirit-giving, and returning Christ against the beastly kingdoms of this world.

Systemic racism is a feature of the Old Testament; peoples who, by virtue of belonging to one nation, oppress outsiders, is a feature of the Biblical narrative. The answer is not political revolution from one idol to another; the answer is Jesus. Now, Iles wants to acknowledge this too; but his Jesus has nothing to say to those oppressed in this world by power structures, because his system somehow wants to deny that power structures can be oppressive. And this, ultimately, is sub-Biblical — especially in that if fails to grapple with the way “Babylon” and beastliness work in the narrative of the Bible from beginning to end (and Egypt before it). Babylon becomes a cypher for Rome in the New Testament; but it really is just any empire that makes power and dominion — a kind of ‘might is right, take what you want’ mentality its fundamental way of life; it shouldn’t be hard to recognise ‘take what you want’ as one of the most basic pictures of sin (think Adam and Eve in the garden), but here’s a little primer on how all this works; and how the Bible is not just concerned about freedom from slavery to Satan, but about the creation of a world where Satan’s pattern of behaviour does not infiltrate and influence human government (whether in the guise of right or left).

In the Bible’s creation account, God’s image bearing people are given this task of exercising power as God’s agents in the world (Genesis 1:27); they are to use this in life giving ways that allow humanity to flourish and multiply; to ‘fill the earth’ — the picture we get of what a filled earth should look like is in Eden. People were made to cooperate with one another as God’s agents, in partnership with God, working in this garden like world, taking natural resources (Gen 2 mentions gold, etc) to spread the conditions of a good and flourishing life. There’s no sense of private home ownership (or even total self-autonomy here, as Adam and Eve belong to each other); there is a sense of God’s ownership and our stewardship. When Adam and Eve desire and take the fruit; when they usurp God’s rule, part of the curse is that their cooperation is broken, and their relationship will now be marked and marred by how power is used (Genesis 3:16). Later, when humans conspire to build Babel — a towering monument to human achievement — God scatters people into lots of nations so that they might not seek this glory and autonomy again. This is an archetypal storyline about the human condition and our relationship with God as creator; the attempt to build Babel is a particularly obvious example of ‘structural sin’ — of people working together to enshrine particular sins as both a very visible ‘norm’ and an architectural feature that would’ve testified and enshrined a particular story about human achievement, power, and dominion.

We’ll come back to the Biblical storyline in a moment — it’s just worth noting some parallel stories from the ancient world; especially in Babylon (the relationship between ‘Babel’ and ‘Babylon’ is not a coincidence). The Biblical story has an interesting relationship with Babylon’s alternative story — its vision of the good life. The Babylonian story does not have a hospitable God who makes a garden and tasks people with fruitful multiplication; in the Enuma Elish, the Babylonian gods are gods of chaos and dominion. The earth is created out of the dead body of a god after a god-v-god war; the winner and chief god, Marduk, gets to build a monument to himself; Babel is ultimately his city, and people are made as servants of this hungry god of power and conquest. This is the story that shapes the life of Babylonian people in the ancient world, and defines their picture of kingship. Those who are outside of this god’s particular people; outside his city; are to be oppressed and conquered and put to work for the people who work for the god. This is based on race. It creates an oppressive group of people and an oppressed group of people. This is before Marx. Obviously.

In the Genesis story, God makes people and eventually these people want to build a stairway to heaven to ascend and take God’s glorious place in the sky; only to have the ‘Babel project’ — their empire — frustrated by God. In the Babylonian world, the gods fashion people but also build Babylon as the city where they descend from the heavens to feast on the earth, enjoying the slave labor of the people they’ve made. The Enuma Elish has Marduk describing his building of the great city of Babylon as a stairway between heaven and earth:

“Beneath the celestial parts, whose floor I made firm,

I will build a house to be my luxurious abode.

Within it I will establish its shrine,

I will found my chamber and establish my kingship.

When you come up from the Apsû to make a decision

This will be your resting place before the assembly.

When you descend from heaven to make a decision

This will be your resting place before the assembly.

I shall call its name ‘Babylon’, “The Homes of the Great Gods”

There’s lots of scholarship out there suggesting that the Tower of Babel is meant to be pictured as a ‘Ziggurat’ — a building functioning as a resting place for the gods, and a stairway between heaven and earth; the Biblical story offers a critique of the sort of worldly power and empire of Babylon right from the beginning (including its vision of ‘images of God’ — who is, and isn’t, an image bearer, and how images are made).

God’s people are not to be “Babylonian” — and part of what defines Babylon is the systemic oppression of those who are not Babylonians. Babylon, as the ultimate destination of Israel’s exile from God, is foreshadowed in Egypt. Egypt is its own oppressive system — a system built on structural or systemic racism. Hebrews are made slaves in Egypt by virtue of their ethnicity. They are oppressed. A system of sin and opposition to God is established that enslaves God’s people; and God cares not just about their pie-in-the-sky-when-they-die spiritual salvation from sin; but a fully embodied emancipation from slavery and systems of oppression; and Israel is specifically not to become an oppressive system; remembering how they were treated in, and saved from, Egypt.

Babylon gives was to Persia, gives way to Greece, gives way to Rome — each of these empires is a human empire built on dominion, and power, and systemic/structural institutionalisation of sin via stories about what it means to be human, the nature of the gods, and why their particular culture is superior to all others (as justification for conquest). Empires in the Bible are systematised sin built around idolatrous worship of things other than God. Empires in the Bible oppress and create victims. God’s people — Adam and Eve, Israel, the church — are called out of empire, out of these systems of sin, and into the people of God so that we become citizens of heaven and ambassadors of Jesus, being transformed into his image. While the so called ‘left’ might envisage an empire built on the destruction of a variety of institutions it deems oppressive, and progress through a reconstruction or redistribution of power from the oppressor to the oppressed — the so called ‘right’ envisages an empire built on power, dominion, and money. It wants to conserve an idolatrous status quo.

Babylon never really disappears; as I mentioned above the book of Revelation equates Babylon with the prosperous market-driven, military powered, dominion of worldly kingdoms — specifically those kingdoms that set themselves up in opposition to the kingdom of God. Those on the Christian right are quick to point the finger at Marxism for its hostility to Christianity (viewed as an oppressor, post Christendom), but very slow to point the finger at the right’s coopting of Christianity for its own power games (*cough* Trump *cough*), or to deny that the status quo in the west could possibly share anything in common with Rome, or Babylon, and be oppressive in its unfettered pursuit of wealth and the good life here and now. Greed is idolatry. Idolatry is inherently destructive. Politically enshrined idolatry is oppressive and destructive to those ‘outside the kingdom.’

Marxism, “cultural” or otherwise, as a systematised vision of the good, not defined by the Lordship of Jesus, is an idolatrous and destructive system.

Capitalism, as a systematised vision of the good, not defined by the Lordship of Jesus, is an idolatrous and destructive system.

Marxism might give us a language and diagnosis of the ills of capitalism, and help us recognise the oppression it creates. But it does not give us a solution if it simply invites us to deconstruct capitalism and change the nature of ‘dominion’ or ‘domination’ any more than a move from Babylonian to Roman rule freed the people of God from slavery and oppression.

Capitalism might give us a language and diagnosis of the ills of Marxism, and help us recognise the oppression it creates. But it does not give us a solution if it simply invites us to deconstruct marxism and change the nature of ‘dominion’ or ‘domination’ any more than a move from Babylonian to Roman rule freed the people of God from slavery and oppression.

To deny that human systems enslave and create victims, oppressor and oppressed, or to suggest Jesus does nothing but automatically save us and provide the good life, is to preach a Gospel that simply enshrines the political status quo, rather than critiquing it through the lens of the Gospel. It is to promote a gnostic Gospel that is only concerned about the Spiritual dimension of life; not a Gospel where Jesus came to offer a different political vision, to create an alternative polis where power is used quite differently.

And this is exactly what Martyn Iles, in his crusade against “Cultural Marxism” is doing; propping up the status quo — capitalism — by spiritualising the Gospel and denying the presence of “victims” or “the oppressed”… Here he is again:

“You don’t need a skin colour to fall into the victim trap. Every one of us can find a way, because every one of us has disadvantages and setbacks in life. That’s the human condition.

But so long as Jesus lives, you are no victim. Not only do you have all the blessings of God’s common grace each day, but He offers you everything, no matter who you are, when you deserved nothing, no matter who you are.

Like I keep saying, the God of the universe offers each one of us the greatest equality in the world. All of us need to get out of our seat in the dust and realise that.”

Iles does not acknowledge the way sin is not just a spiritual reality affecting our relationship with God, but a reality affecting our treatment of one another; that sin affects the experience of people in the world, and that this clearly affects some people disproportionally (think the Hebrews in Egypt). Faith in Jesus does not automatically end oppression; the return of Jesus to make all things new does; a world free of sin, and curse, and beastly governments. Iles ends up preaching an incomplete Gospel because he has a narrow view of sin, and so a small Jesus. He says of the anti-christ left:

“The “facts” that lie at their roots are popular deceptions. A supposed underclass of children oppressed by heteronormativity… horrifying, systemic racism by police officers… an imminent ‘end is nigh’ style climate catastrophe… Jesus as a figure concerned mostly about the earthly ‘oppressed’ and mostly for their empowerment in earthly systems.”

I’d say Iles himself ends up with a Gospel that minimises the importance of the divinity of Jesus and the Triune character of God by elevating the political; with a Jesus more concerned about righteousness, natural order, and sexual purity than those oppressed by injustice the abuse of power, denying the impact of sin on the physical world (whether the environment or human relationships), and a Jesus who is only interested in some disembodied heavenly future. A Jesus you don’t find in, say, Luke’s Gospel.

A Jesus who arrives on the scene as Caesar Augustus is flexing his muscles and measuring his empire with a census; a Jesus whose arrival is announced as an expression of God’s character, the God who, in Mary’s song:

“He has brought down rulers from their thrones

but has lifted up the humble.

He has filled the hungry with good things

but has sent the rich away empty.” — Luke 1:52-53

Who launches his ministry in Luke by announcing Jubilee; freedom for the oppressed, who then sets about contrasting his kingdom to the kingdom of Herod, Caesar, and Satan.

“The Spirit of the Lord is on me,

because he has anointed me

to proclaim good news to the poor.

He has sent me to proclaim freedom for the prisoners

and recovery of sight for the blind,

to set the oppressed free,

to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favour.” — Luke 4:18-19

There’s certainly a spiritual dimension to Jesus’ announcement; he is announcing the end of exile. But there’s also a physical dimension to his announcement; he is announcing the breaking in of the Kingdom of God. This isn’t news to Martyn; the ACL’s whole schtick is attempting to enshrine and create a certain vision of the kingdom of God here on earth, in part through worldly institutions, it’s just this kingdom looks a lot like ‘the right’… and a lot like victory over ‘the left’…

In the meantime, Christians have an alternative political vision to both Marxism and Capitalism; both left and right, and are also free to adopt the critiques of worldly power (and language) from those critiques in order to make the Gospel known. There will be Christians who, because of experience or observations of the world will be particularly attuned to the beastliness of capitalism and the worship of money and power, just as there will be Christians who will be attuned to the beastliness of ‘woke’ marxism and its deconstruction campaign. It serves nobody to label one side of that equation “antichrist” — so long as they’re not denying Father and Son in their politics.

If those on the right feel free to throw around “Cultural Marxism” as the greatest evil, they shouldn’t be surprised if those on the left throw around “Capitalism,” “systemic sin,” “systemic racism” or “black lives matter” in response. There’s a better way than the culture wars, inside or outside the church… The way of Jesus. Who calls us from all forms of idolatry, to have relationships redefined by a new form of worship and a new politics.