Modern life is complicated.

This piece is both about that complexity, and how hard it is to make good ethical decisions, and about the current conversation about how a potential Covid-19 vaccination uses cells from abortions conducted decades ago.

The Sydney Anglican Archbishop Glenn Davies has described use of human tissues from abortion as ‘reprehensible,’ and he, and others, have suggested use of this vaccine is now a conscience issue for Christians. The Catholic Archbishop of Sydney, Anthony Fisher, said, in an article urging the Government not to create an ethical dilemma, that news of a Covid Vaccine seems great:

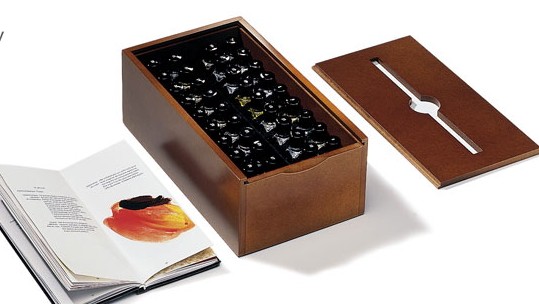

“Until you read the fine-print on the ampule. Turns out that this vaccine makes use of a cell-line (HEK-293) cultured from an electively aborted human foetus.”

He said, further:

“Of course, many people will have no ethical problem with using tissue from electively aborted foetuses for medical purposes.

Others may regard the use of a cell-line derived from an abortion performed back in the 1970s as now sufficiently removed from the abortion itself to be excusable.

But others again will draw a straight line from the ending of a human life in abortion, through the cultivation of the cell-line, to the manufacture of this vaccine. They won’t want to be associated with or benefit in any way from the death of the baby girl whose cells were taken and cultivated, nor to be thought to be trivialising that death, nor to be encouraging the foetal tissue industry.”

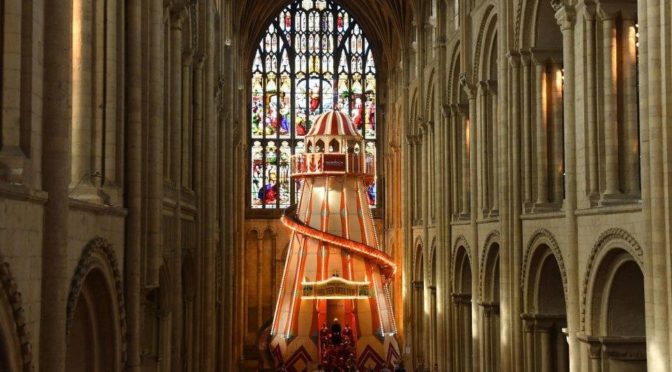

There’s a beautiful picture of just how complicated in the Netflix series The Good Place, where modern people have stopped being good enough to earn a ticket into the afterlife because of how deeply enmeshed modern systems are — even when it looks like we’re doing ‘good’ things, the system runs a long way down and our actions are almost always the product of a system that involves some evil. Really obvious versions of this involve supply chains for the goods we purchase in the western world; I might buy some baby clothes to donate to a new mum, but I might buy them from a source who have slave labour in the supply chain for both the raw materials and production of those clothes; at which point I am complicit, whether I know it or not, in propping up that evil.

The Good Place makes the case that, whether knowingly or not, being complicit in evil is inevitable. Knowing that we’re complicit presents a dilemma, because, from that point on, we can’t claim ignorance as a way to mitigate our culpability.

This makes doing the right or good thing pretty tricky; and might just lead us to a fatalism that says evil is inescapable and so we should just do what we want, or what seems best to us, as individuals, without tackling the complex systemic issues.

The Good Place was an attempt to at least frame that conversation in a world without God in the picture; it provided its own answers with a sort of virtue ethic built on love for others and the pursuit of happiness in the realms we can control; it offered a humanist approach to the dilemma of complex, systemic, sin.

The Bible has both an account of and a solution to, complex, systemic sin, and a guide for how to live in a complex world where all human behaviours intersect with evil and are complicit in benefiting from evil. There’s a stream of Christian ethics developed from this understanding that the world as we know it is not ‘turtles all the way down’ but ‘frustrated by sin and curse all the way down.’

The Bible accounts for systemic sin with a vision of humanity that starts in our hearts and minds; we’re actually not capable of pure altruism that only benefits the other and has us escape from the system; at one point in Genesis, God looks at humanity and the human heart, and declares our hearts to be ‘only evil all the time’ (Genesis 6:5). The ‘good’ that we do, even as those still made with the capacity to reflect the image of God in the world, is inevitably tainted by complex mixed motives and especially self-interest.

This is one way that people from the Reformed theological tradition, following Calvin and Luther, have understood ‘total depravity’ — the idea not that all our actions are absolutely depraved, but that sin and its effects are such that all our actions are the actions of hearts tainted by sin; Luther borrowed Augustine’s idea of the heart curved in upon itself; which is a nice picture — even as we offer love for others, or for the world, there’s a self interest in the mix.

One way the Bible unfolds with this in the background is that no person is capable of righteousness, or doing good, until we meet Jesus in the story; the righteous one. This means that as good happens throughout the story of the Bible it happens through God’s actions in the world and despite human failings; the Old Testament is full of figures who do evil stuff, but who God still works through — sometimes, even, God works through people whose hearts have been hardened towards him, like Pharaoh in Exodus (as Paul explains this in Romans). Sometimes what we intend for evil, God can use for good — this is true of, explicitly, Joseph’s brothers sending him into slavery in Egypt for evil reasons (Genesis 50), but is also true of the execution of Jesus; an evil, sinful, expression of human selfishness (as the Bible frames it) that we intended for evil, but that God used to bring goodness and life; this act from God, through the righteousness of the son, is one where we’re either complicit in a way that brings death and judgement on us, or one where we find — in the fruits of that evil act — that is, Jesus body broken and blood poured out — eternal life. Good is retrieved from this act; Jesus, obviously, is willing in this moment in a way that Joseph was not so much (that’s the point of his visit to the Garden of Gethsemane, where he says “not my will, but yours” and then goes on to be arrested, tried, and executed as an act of selfless love for God, and for those who will find life in him).

Even as we seek to do good, we’re caught in a world made by people who operate in self interest, and who sometimes operate in a sort of self-interest that doesn’t love others; especially distant others. Our inclination, self-interestedly, is to love those neighbours we get the most back from; those we’re most proximate to (who can effect our well being the most); the distant vulnerable aren’t always on the radar (see how easy it is to cut foreign aid, especially without seeing what that does to a complex global system, or worse, because we do see what that does to a complex global system and want to maintain a status quo of inequality so we get cheap stuff). We cannot actually escape benefiting from sin or evil. This is the system we live in and benefit from; even, for example, Centrelink payments come from taxes raised by the government, including taxes raised from gambling, and mining, and other industries that make money from sin. They’re handed out by a government that makes legislation that promotes sin (for eg, greed), and pays an army that engages in many military activities, not all of them ‘just wars’.

David Foster Wallace captured this in his famous This Is Water address; where he said this selfish default drives a world of “men and money and power’ that hums along in a pool of “fear and anger and frustration and craving and worship of self,” our lack of inclination to upend this status quo comes because “our own present culture has harnessed these forces in ways that have yielded extraordinary wealth and comfort and personal freedom. The freedom all to be lords of our tiny skull-sized kingdoms, alone at the centre of all creation.”

The account the Bible gives for this systemic mess is that we turned from the life giving God towards autonomous self rule; to self worship (as Wallace put it); this starts in the first pages of the Bible with the story of Adam and Eve, who reject God’s good design for a world in harmony with him; a role bringing goodness, fruitfulness, order, and love — Eden — to the whole planet, and so instead of the whole earth being made as Eden, the world is cursed and frustrated, and people are exiled from God’s presence and the relationship with him that would shape our hearts.

When Paul reflects on the human heart, and its entanglement with a systemically broken world, in his letter to the Romans, he says the system we all end up being shaped by, this system of sin, starts with a decision to worship and serve created things instead of the creator (Romans 1), after a lengthy working through just how bad what the Bible calls sin is for us, our relationships, and our destiny, and how God does something about this with a new pattern for humanity in Jesus, his death, resurrection, ascension, and pouring out of the Spirit — so that we can be forgiven, and share in a new humanity (by sharing his death and resurrection) — Paul lands in Romans 8, where he talks about ‘creation’; the whole world; being frustrated by sin; captive to sin. It’s not turtles all the way down, it’s sin. In Romans 7 he describes the human experience without God’s Spirit as being one where even if we know what good things we should do, we can’t — our idolatry means our hearts are curved not towards God, but towards created things, and ultimately towards ourselves.

Idolatry is serious business. It destroys life; it creates systems of mess. So, of course, Christians who are trying to live a new life in Jesus — where we share in his death and resurrection, and receive his Spirit to liberate us from bondage to curse and sin — are meant to ‘not conform to the patterns of this world, but be transformed by the renewing of our mind,’ as we worship God properly, ‘offering ourselves as a living sacrifice’ to God (sharing in the death of Jesus, one might say). The false worship in Romans 1; where ‘self’ rules, is replaced by a different picture of worship — where we give ourselves in love; where we put self interest to death (a theme Paul picks up on repeatedly in his writings, most clearly in Philippians 2).

Idolatry is a picture of the systemic complexity of the world, for Paul, it is both a symptom and a cause of systemic mess and sinful behaviour. One way this complexity manifested itself for first century Christians was in food sacrificed to idols. At a physical level, idol food was still food. It still nourished the body and gave life; it was still meat from an animal that God made. If it landed on your table and you had no understanding of its provenance, you’d be hard pressed to know the difference.

This is a bit like if someone gave you a cotton shirt today, with no label, it might be difficult for you to tell whether that shirt came from a sweatshop, or was ethically produced, or whether the cotton came from an Aussie farm, or from slave labour internationally… you might eat that meat with a clean conscience (or wear that shirt). But once the provenance is made known; after that first bite, or first wear, you’re faced with a new dilemma.

You’re being asked to decide if more bites, or more wears, make you complicit in a whole sinful system, and what that means for you.

The more ubiquitous the meat in the marketplace or shirt in the clothing store, the more difficult it is to avoid such complex ethical questions and participation; in fact, it is almost inevitable that our consumption of goods in this world will be a product of sin and evil (see David Foster Wallace’s description of the default system); in the form of idolatry; and some sin and evil will be more palatable to us than others (for Christians, where we’ll get to below, it’s interesting to ask why abortion is a conscience issue around a Covid vaccine, where sweatshop labour, or supply chain issues, don’t seem to challenge us so much on a daily basis in our consumption of goods).

Paul addresses food sacrificed to idols on two occasions in his writing in ways that I think are helpful for framing the present day conversation about Covid-19 vaccinations and cell lines coming from two aborted foetuses. I’ll unpack a little bit of what he says in Romans and 1 Corinthians, and the principles for ethics in his working out that issue; touch on some key teachings of Jesus that I think are in the mix for Paul and us (on these questions), and then, against the backdrop of acknowledging how complex the modern world is, and how it’s sin all the way down, ask how we might best approach issues where we are being made aware of sin in the provenance of something we’re being invited to partake in; so that one might act according to conscience. I’ll sum these up in a nice numbered list at the end. So feel free to skip to that to see if this whole thing is worth reading.

How one approaches an ethical question like whether to eat food sacrificed to idols, or whether to receive a vaccine that comes from a questionably sourced line of cells, or prosperity in a nation built on stolen land and the genocide of its first peoples, will be the product of one’s ethical system (and often there’s a political shortcut here, where we outsource our ethical thinking to chosen leaders).

It is interesting that the people most loudly opposed to the use of this vaccine are those most interested in individual sin, from a particular paradigm, rather than systemic sin. That’s an ethical outlook. There are lots of ways to do ethics; our default western method is utilitarianism, where the ends justify the means (who cares where the vaccine comes from so long as it works and is safe), some Christians like divine command ethics (our job is to act where God has spoken clearly, how he has spoken, and to discern what he might command of us if he is silent) — in a complex modern world, people from this camp are often looking to create new black and white rules where none have previously existed. Duty ethics are closely related to divine commands; where we have a duty to obey God, but also any legitimate authority he has created (church leaders, denominational articles/confessions, the state (depending on how one reads Romans 13 etc).

These systems will all ask questions about whether it is ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ to take a particular course of action, with a different authority in the mix (the results, God, the authorities one recognises who establish a duty for us — even nature, in some forms). Another form of ethics; virtue, or character ethics asks not so much ‘is this action right or wrong?’ and ‘who says?’ but ‘am I acting rightly as I take this path’ — virtue ethics can both recognise how inevitable sin is in a messed up world, and provide a way forward that focuses not so much on choosing the lesser of two evils, but on being as virtuous as one can be in a given situation.

There are lots of ways to frame virtue ethics; I love a combo approach that brings Alisdair MacIntyre’s After Virtue together with the Christian story; the type articulated in Stanley Hauerwas’ A Community of Character: Towards a Constructive Christian Social Ethic. Hauerwas, as an anabaptist, is very committed to the idea of systemic violence; the impact of sin ‘all the way down’ — he particularly draws that out with reference to the modern state (or kingdom) as essentially a violent, military, enterprise. I’m sympathetic to a criticism of anabaptist ethics that it ends up seeing people disengaged with worldly institutions, and always operating in parallel (and I like James Davison Hunter’s response to Hauerwas in To Change The World); but Hauerwas is bang on the money in his willingness to see sin impacting systems, and to call for an alternative system that radically reshapes our ethics and our understanding of character and virtue.

Incidentally, there’s a terrific piece on Christianity Today from David Fitch, who is a guy with anabaptist sympathies who wrote a book unpacking some of Hunter’s ideas around “faithful presence” critiquing Tim Keller’s recent paper on social justice and critical theory that is worth a read. I also think given the complexity of modern life, where it’s sin all the way down, the question is not ‘how do I avoid evil?’ — if evil is inevitable — it’s not even ‘how do I pick the lesser evil?’ But ‘how do I do what is most loving?’ It may be that this sometimes means choosing not to participate (in a trolley problem type scenario, you actually never have to pull the lever), but it should always, for Christians following the example of Jesus (and secure in the results that the evil done to him produced for us), involve a heart not curved in on the self, but towards God and others by the Spirit. Modern ethics requires some of us to stand distant enough from the fray, with a degree of purity intact, so that we might ask questions about the status quo, and some of us getting our hands dirty in the mess and muck of compromise in order to work towards change. We need both Anabaptists and Anglicans (but maybe not Anglicans who act as Anabaptists).

Idol food in Corinth and Rome: A path for navigating ethical dilemma in complex and sinful systems

I think Paul, in both Romans and 1 Corinthians, champions an ethical system built on the commands of Jesus; specifically, the command to love God (above idols), to love one another (those within the Christian community), to love one’s neighbour (such that they are clear about God and idols, and might become clear about the love of God for them); and that he leaves navigating life this way as a matter of freedom, conscience, and character rather than in the realm of rules or results. Here’s some of the data.

Paul says:

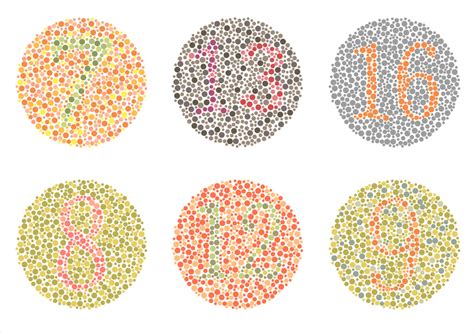

1. Even though idols aren’t real and people should be free, then, to enjoy idol food as meat made by God, some people don’t know this (1 Corinthians 8:4-7). This knowledge gap is a relational reality; and this makes the right thing to do disputable, rather than black and white (a question, perhaps, of ‘ethics’ rather than law or divine command.

This model doesn’t immediately map on to the vaccine question; because the abortions in question were real and sinful (just as the idolatry in the meat sacrifice was real and sinful); and the vaccines are a fruit (some time removed) of that sin (just as the meat is), part of Paul’s logic is that these idol statues aren’t actually real (not that the sin isn’t), they haven’t magically changed the meat.

Now, it’s worth teasing out that part of Paul’s ethical framework, at least in Corinth, is the idea that ‘an idol is nothing’; that the meat in question is simply a clump of cells, and that meaning is created by the way the cells are framed. An aborted foetus is not nothing, it is someone. The question here is different, but there are similarities too. Abortion, in the form we experience it in the modern west, is not just a health issue (such that one might decriminalise it), but also a biproduct of idolatry (have a look at the behaviours that Paul lists in Romans 1, and you’ll see the behaviours that produce lots of the modern demand for abortion). This means the parallel is not exact; and yet, while the cells used in this research come from people; unborn babies; unborn babies who experienced an evil (so far as we can tell, or assume, without knowing the medical and social circumstances around these abortions — though the letter from the Archbishop says they were from an ‘elective abortion’), the cell culture involved has been duplicated over and over again in a chain for decades, it is not so straightforward to argue that the cells that exist now are ‘the person’ who was aborted then. It is clear we’re not, in this instance, talking about the ongoing trade of foetal tissue from elective abortions; though this sort of research justifies the ongoing trade of aborted persons for scientific research, and certainly prevents the status quo being changed to make abortion less commercially or scientifically attractive. Part of the conscience question facing us is whether using this vaccine, or this cell line, rather than other options, props up, or justifies, a system that should be torn down; the other question is about what good might be retrieved from that historic evil (not an ends justifies the means argument) for the sake of people now.

The human tissue cultures used in these vaccines is intrinsically connected to the sin in a way the meat isn’t (the meat was a good creation from God, taken by people to do bad things, but there was an original purpose for that meat connected to God’s glory which can be redeemed — receiving it with thanksgiving (1 Timothy 4); the cells were a good creation from God, but the human intervention means they can’t be directly redeemed for that purpose — the life of the person who was aborted, though a vaccine is life-giving it isn’t in the same form that God gave the material substance in question; and yet, is also disconnected by time and duplication in a way that makes the question less clear cut (and a matter of conscience), and a ‘good’ can be retrieved from that evil, which is a pattern we see from God through history, and particularly at the cross of Jesus, where a life is taken that then gives life to others.

It’s a complex question; the issue is that some people will inevitably, now, think that anybody who receives this vaccine is complicit in evil. Their consciences will be seared, and it is likely this searing will create division between those whose consciences are clear, and those whose aren’t.

2. How we approach these conscience issues and areas of freedom really matters because of the way those who are a little more black and white (the ‘weaker conscience) perceive your exercising of freedom, and when they choose to act against their conscience, while following your example, or choose not to care about the sin at the heart of the question, because they think that is what you are doing; they do the wrong thing (1 Corinthians 8:9-13). If you’re going to articulate a position on a disputable issue it seems important to make it clear that it is disputable and not binding (like Paul is, himself). And if you’re going to say an issue is disputable it inevitably means making space for the ‘stronger’ position to actually be the correct one (if it is possibly true and explicitly not illicit). In Romans, Paul unpacks this a little more, he says ‘don’t participate in a thing’ if to do so makes your Christian brothers and sisters believe you are supporting evil/idolatry and so leading them to do something against their own conscience.

3. Because life is complicated and often figuring out how the wise and good path is ‘disputable’ rather than clear cut, Paul is keen for people to venture into discussions like this carefully and without quarrels; that means both those who are ‘strong’ and those who are ‘weak’ — that is those who think to participate is to be sinful and complicit, and those who think it isn’t — should make room for one another in Christian community and not break fellowship over the question (Romans 14:1-4). Part of his logic is that ultimately all of us have to give an account to God for our decisions (Romans 14:4, 7-13). But, digging in to questions like this and arriving at a position of conviction in ‘your own mind’ (Romans 14:5) is a good thing (especially in a mind being transformed and renewed by the Spirit and your true and proper worship ala Romans 12). He’d prefer people focus on unity in Christ, and things that will build that, than that they venture into disputable matters in ways that either offend or bind the conscience of others (Romans 14:19-22), and yet also says to ‘not let what you know is good be spoken of as evil‘ (Romans 14:16), and is, himself, writing a letter that got published in a pretty successful book making a particular case.

4. If you decide that to receive this vaccine is sinful, it is quite possible that you are wrong (and I think you are, as I’ll unpack below), but if that is your conviction, then to receive this vaccine is a sin (Romans 14:14); not an unforgivable one, but the lesser of two evils is still evil if you think you’re choosing ‘an evil’. Any deed not done as an act of faith(fulness to God) is sin (Romans 14:22-23).

5. Paul’s ultimate ethical questions are faithfulness to God and relationship with him (Romans 14:7-13), and love for neighbour (especially, but not only, fellow Christians) (Romans 15:2-7), but also explicitly that we act in such a way in society that builds relationships and models the Gospel to non-Christians (1 Corinthians 10:21, 33). His priority is not self-seeking. As he invites people to “come to your own conclusions” he also invites us to recognise that you aren’t only an individual; as a Christian you are both united to Jesus (and you belong to him), and you are a member of a particular community of people (the body of Jesus, the church), and that communion matters more than your individual freedoms (Romans 14:7-9). Paul would rather abstain from meat all together than cause another to stumble (1 Corinthians 8:13, Romans 14:13-14); this is another point where the comparison is inexact. To not eat meat is fine, there are vegetables that are nourishing. A vaccine in a pandemic is a slightly different sort of health question than a question of diet preference; and, the Archbishops have also said that if it’s a choice between this vaccine and none, they think this vaccine would be a ‘good’ rather than an evil. Because the stakes are a bit higher (it’s not just about diet, and there are anti-vaxxers in the mix who are, at times, from a Christian fringe), I think there is a case to be made that the ‘stronger’ should actually be speaking up strongly in favour of vaccination as an act of love for neighbour (while perhaps questioning supply chains). To this end, I think the letter does a reasonable job, but the reporting of the letter makes the dilemma a little more black or white than either Archbishops Davies or Fisher were.

6. Don’t be an idolater at idol temples. It should be clear to people you belong to a different world and worship a different God (1 Corinthians 10:18-22). The equivalent here would be that it is enough for people to know that you aren’t complicit in abortion if you aren’t participating in the abortion industry, or seeking a termination. It is quite possible that our public opposition to the sort of world that produces an abortion industry that sells human body parts will be enough to make us not complicit in the evils connected to this vaccine’s history, but also to have an ethical model that sees some good retrieved from that history in the form of this vaccine (not in a way that justifies the continuation of the practice). Our true worship (offering ourselves as living sacrifices) and what we say yes to, including the ways we show that we value human life, will do more to frame our engagement in these issues than what we say ‘no’ to. In Corinth, the way they were meant to share in the Lord’s table, as they gathered (which they were failing to do very well) was part of the mess where people’s participations at other tables called their loyalty to Jesus into question.

7. If a thing seems to be a good thing that can be received as an act of faithfulness, not explicitly idolatrous, you are free to participate (1 Corinthians 10:25-27). It isn’t necessarily wise to raise questions of conscience when they wouldn’t otherwise be raised. In Corinth, unless meat came from a kosher butcher, all meat was connected to the idol temples and the meat market. It wasn’t that the status of the meat was likely to be idol-free, it was that asking made an issue of the connection. Don’t go digging into the provenance of a thing if you aren’t prepared to act on the information you then receive; but if you receive a thing that appears good without knowing its illicit provenance, you haven’t sinned. Once you’ve got that information you’re in conscience territory.

8. It’s not just conscience territory, but appearance territory. In fact, Paul says the biggest deal is not your own conscience, but the consciences of others — it’s if the people on believe your action is supporting the idolatrous status quo because you are a participant — that makes him take the position he does (1 Corinthians 10:28-29). So ‘don’t participate in a thing’ if to do so makes your non-Christian neighbours believe you support evil/idolatry.

Retrieval and Love: An ethical system for disputable matters in a complicated world

In his The How and Why of Love, Michael Hill develops an ethical system that is kingdom oriented, shaped by a Biblical theology that positions us as those awaiting the return of Jesus in a complicated and fallen world where there’s sin all the way down. He says it’s not enough for us to simply say ‘this is what God’s kingdom looks like’ and do that, because we’re not there yet, but also that the character of God’s kingdom is caught up in the great commands of Jesus, to love the Lord your God with all your heart, and love your neighbour as yourself. He takes a teleological ethic that says “an act is right if and only if it promotes the kingdom of God,” and shows that the kingdom is a kingdom of loving relationship between God and humans, individual humans, groups of humans, and humans and the created order,” and also “inner harmony within each human.” When I teach this to my RI kids I talk about how God made us to love him, love each other like we love him, and love the world like he does. That’s our purpose; that’s what the kingdom looks like. Hill’s restatement of an ethical system of ‘mutual love’ says “an action or trait of character is right if and only if it promotes (creates or maintains) mutual love relationships between (a) God and humans, and, (b) humans and humans.” Because we live in a world that is not yet ‘the kingdom of God realised,’ Hill suggests a “retrieval ethic,” where “in the context where hardness of heart prevents the accomplishment of the goal of mutual love, love would seem to necessitate the retrieval of as much good as possible, or, at least, the reduction of harm.” He distinguishes this model from the ‘lesser of two evils’ approach because here one is not choosing to justify evil, but rather, seeking to do what is most loving in a bad situation (a sort of virtue ethic, where our understanding of love is shaped by the Christian story, and particularly God as creator and redeemer, through the cross of Jesus, the resurrection, and the gift of the Spirit), and the “kingdom ethic” model where we are told to act as though the kingdom is already fully realised (or as though that’s our job).

Hill does have a chapter on abortion in his book; one that touches very briefly on the use of cells in research. He doesn’t dig into that as a picture of retrieval, but instead, outlines a thoroughly Christian vision of the unborn foetus being fully human. Once that life has been taken though, as was the case decades ago, the ultimate good to be retrieved would be the retrieval of a view of their personhood, and their dignity, and the tragedy of the loss of life involved; we’re decades down that chain now, which is why Michael Jensen’s piece on the ABC’s Religion and Ethics portal is a useful vision of what it might look like to both retrieve that good, seeing the personhood of the unborn child, and the good of the medical research, that has emerged from their tragic death, including the possibility of this vaccine.

Here’s how I’d approach this particular vaccine, through an ethical grid supplied, in part, by Paul’s approach to food sacrificed to idols.

1. The complex world we live in means every act in a network of relationships, or culture, or system, or nation, is tainted by sin. We can’t avoid corruption from the fruits of idolatry.

2. Something more than ‘don’t partake in evil’ is required.

3. Adam’s original sin was partaking in something that had been declared sinful by God, something more than ‘partake in evil without worrying about it’ is required.

4. The law, or ‘divine commands’ in Christian ethics is ‘the floor’; love for God and neighbour (and the imitation of Jesus) is the ceiling.

5. Our ethical systems should compel us to imaginative love and virtue, not just right (moral) decision making.

6. Conscience is a really big deal in Paul’s ethical system; but he always implicitly sides with the ‘strong’ conscience while accommodating the weak; Christian leaders should avoid binding the conscience of others in case they are the weaker brothers and sisters on an issue and they unnecessarily bind the conscience of another by making an issue of provenance where none exists.

7. If we’re going to raise conscience issues on one sin of particular concern, it’s worth being consistent (asking questions about church institutions and their investment policies, super funds, environmental policies, etc, etc). Once we acknowledge complexity as a conscience issue in one area we better be prepared to follow that up with consistency.

8. God retrieves good things through human sin and evil; we are not God, but we might be prepared to adopt a similar posture of seeking to retrieve goodness, love, and life-giving approaches for the sake of our neighbours in good conscience, making the best of it.

9. That there are some goods retrievable from abortion (in the form of this vaccine), in no way justifies those particular abortions involved, or abortion in general. The end does not justify the means.

10. If Christians are never to participate in evil, when the complexity of systemic evil is made known, then we must create parallel institutions like schools, banks, libraries, etc; not to mention an alternative political state (especially in Australia); a paradigm of working towards good as redeemed people who, by the Spirit, are now able to curve our hearts away from ourselves to some degree, towards love for God and neighbour, then a more helpful paradigm for our ethics is ‘am I being Christlike in this situation’ and a working towards retrieving good.

11. True retrieval and love for both God and neighbour, in the face of complexity, means not turning a blind eye to evil or sin, but staring it down, and acknowledging it. Rooting it out of our own lives, but also seeking to change and challenge the systems we find ourselves in (across the board). Speaking out about questionable provenance of ‘goods’ that we seek to consume is one part of a step of undermining such a market, or status quo, creating genuine alternatives has to be part of that picture too. I think it’s a good thing that the Archbishops from these denominations have raised questions about the provenance of the Oxford vaccine, I think it would be great if other vaccines are pursued instead, but if they are, or aren’t.

12. Vaccines are a way we love our neighbours. The anti-vax movement is often built on an individual ethical paradigm (what is loving for self; often built on personal utility around minimising personal risks), rather than a community/relational one (what is loving for others and for God). Questions about the provenance of a particular vaccine aren’t questions about vaccinations in general.

13. The solution to a complex and messy system is the renewal of all things by Jesus, not the righteousness of us people. This doesn’t mean doing nothing; it just means our actions won’t be enough to solve the problem of sin and curse — either systemically or in our individual lives. We live our lives simultaneously recognising that creation is subject to frustration, and that we are, by the Spirit, the children of God the creation is waiting for in eager anticipation; how we tackle sin and mess now anticipates the return of Jesus to make all things new; removing sin, and curse. This is the story that answers the question ‘who am I?’ that provides the answers to the question ‘how should I live?’

14. You should not get a vaccine that is a byproduct of abortion if that is a conscience issue for you; that is, if you think you would be sinning if you received the vaccine voluntarily.

15. You should not subject other Christians to your conscience based assessment of the morality of the vaccine.

16. I do think whether or not one chooses to partake in the Oxford Vaccine is a matter of conscience similar to food sacrificed to idols; and one shouldn’t publicly trumpet your choice as a matter of Christian freedom that destroys a weaker brother or sister, but, nor should we not say anything; finding the balance of speaking like Paul did, and adopting a position on a contentious issue without delegitimising the positions of those who arrive elsewhere is a question of wisdom and imagination.

On balance, given the retrieval framework, it is, in my summation, a ‘good’ to receive this vaccine as an act of love for those neighbours presently alive, whose health and well being and ‘life’ (in pro-life terms) will be positively impacted by your decision.

But this last statement also has to be carefully qualified; and this is how I think I’m discharging that responsibility to not let something ‘good’ be called ‘evil’ in a disputable zone… On balance, personally, and without seeking to bind the conscience of others; I can say:

- modern practices around abortion are a sinful failure of love for neighbour (the individual unborn neighbour, but also the system that makes abortion desirable represents a failure to love those in our community who might seek an abortion),

- through the evil of abortion, in the case of this vaccine, some goods might be retrieved that allow love for neighbour in a different form (vaccination),

- that to participate in those goods is not simply to participate in, or be complicit in, evil. In this I’m drawing an analogy here between the outcomes of idolatry (food sacrificed to idols, and abortion), and whether Christians can partake in free conscience, our knowledge of the sin involved in the production, promotion, and use of this vaccine, and whether our participation is perceived as making us complicit (or makes us complicit in the ongoing idolatry).

- to participate in promoting and receiving this vaccine, while alternative vaccines might not be caught up in the same sinful system, might not be the most good and loving thing that I can do.

- other vaccines will also inevitably be the product of other forms of sin (greed, immoral conduct, commercial enterprises built on various problematic practices or products),

- our job is to act as people motivated by love for God, and love for neighbour,

- a covid vaccination with widespread uptake in the community is a part of love for neighbour during a pandemic, but even this will involve a complex mix of systemic sinfulness, and possibly even my own selfish desire to preserve my own life, possibly at the expense of others rather than for their good.

- so, there are more constructive approaches to ethics, and things for us to be talking about and doing as Christians. We might be better off focusing on positive alternatives than highlighting negatives; as a citizen in Corinth might have been better off giving and seeking hospitality with their neighbours, seeking to save the lost to reduce demand for idol food, or starting their own meat markets, rather than policing the food served up in a complex and messy world.

17. In all this, because the world is complex and our hearts still curve in on themselves, none of these actions or positions will totally avoid sin. Participation in sin in this world is inevitable. The Good Place had the diagnosis right. The answer is not that I live a good or ethical life of love though; I can not. Christian ethics are always a response to God’s grace and forgiveness received through Jesus. Whatever point you land on in this complexity (I hope this post is long enough to have earned this…) Jesus is the ultimate vaccine, and he protects us from the deadly consequences of our curved hearts.