I’ve spent a fair portion of my time in the last two years entering arguments with atheists online. These are different to arguments with atheists in real life. Steve Kryger at Communicate Jesus has posted a couple of thoughts on this matter lately – and even been roundly panned by an atheist blog for his trouble. Steve’s posts:

- Why I’ve decided online religious debate is a bad idea

- Why debating atheists online is a fruitless pursuit

- Where are the Christians?

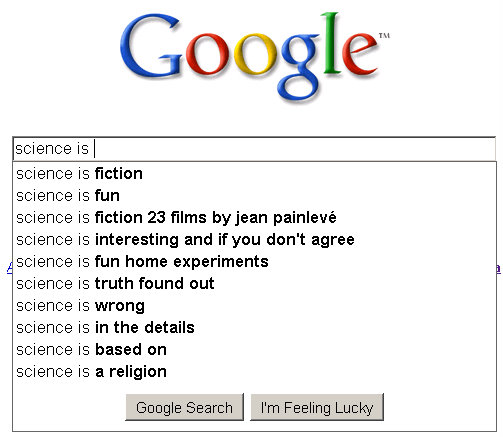

My motivation for doing so has been twofold – on the one hand, I don’t like seeing people bagging out Jesus without anybody mounting a defense, and on the other, I realise that people google for all sorts of things and read blogs and their sycophantic comments to help make up their minds. I want to present Jesus as an alternative worldview to militant atheism.

But I’m on the verge of giving up. Here are eight lessons I’ve learned (at times the hard way) from arguing with atheists that have left me close to pulling the pin on this particular avenue of evangelism.

- If you argue with atheists online, especially on their turf, you will almost always be outnumbered. There’s something about the nature of community that stops Christians using the Internet the same way atheists do. I suspect it’s because atheists are a minority with no real world equivalent to church. They meet virtually. They encourage one another through forums and blogs. The Internet, in my opinion, is their nexus of community.

- Being outnumbered makes actually engaging with arguments hard. If one hundred commenters on a forum each ask the token Christian a question and that Christian only picks three to answer (which is a 3:1 comment ratio ie those hundred post one comment each, the Christian posts three) then the forum often jumps on the one person, suggesting that they are being duplicitous or purposefully evasive. It’s a trial by numbers and “victories” are awarded to the masses.

- If you’re going to talk about science, logic or morality you need to be careful to frame your terminology accurately. If you want to engage and give a good account for yourself you need to be familiar with strawmanning, Godwin’s Law, ad hominem, Pascal’s Wager, and the “no true Scotsman fallacy” – Christians are often guilty of transgressions of the first two, the chances of an atheist resorting to an ad hominem attack in response to a Christian rapidly approaches one the longer the conversation continues. Atheists think they’ve debunked Pascal’s Wager, while the “no true Scotsman fallacy” is a favourite “trump card” they play in order to lump all theological beliefs together so that they can strawman us.

- Atheists have no interest in nuance. They don’t pay any regard to context. They interpret everything literally – be it text from the Bible, sarcasm in discussion (or irony), or anybody’s claim to be a “Christian.” They love quote mining – especially from the Bible. I’ve seen atheists take bits from Jesus’ parables to suggest that God wants his followers to put people to the sword. They aren’t interested in theology, they aren’t interested in why Christians can justify believing things they find abhorrent, they won’t ever really put themselves in “Christian” shoes when understanding things Christians say – they prefer to maintain distance because it’s easier to ridicule the “other”.

- “Christians” are your own worst enemies in these contexts. A week’s worth of reasoned and fruitful discussion can be very easily undone by one comment made without being mindful of presenting the “truth with love.” Stupid “Christian” statements, along the lines of the Answers in Genesis billboard advertisements form last year spend any credit lovingly Christ centred arguments develop.

- Most “atheists” are antitheists, most hold atheism at the core of their identity – but this is not true for all of them. You can’t generalise when describing atheists – some are like Dawkins who are atheists through a philosophy of scientific naturalism and evolutionary biology through “natural selection” – this view leaves no case for a creator, others are ex-Christians who had rejected all other gods already, and have since rejected God, some, like Christopher Hitchens, seem to be atheists philosophically first, and scientifically second. Each atheist is an individual. This is part of their problem when dealing with the “no true Scotsman” fallacy. They think self definition is all that matters for assessing claims – there are, in fact, external issues to take into account when deciding if a Christian is a Christian.

- You’ll almost never change anybody’s mind online. Particularly if you’re outnumbered. They who shout loudest win. Ten idiots in a room yelling loudly will always feel like they’ve beaten one genius speaking quietly.

- Your best bet in these situations is just to bring everything back to a question of the historicity of Jesus and his resurrection, this, after all, is the lynchpin of our belief. If they can disprove the resurrection then our faith is in vain. And it’s this argument that needs to be convincing. Questions of science and methodology are secondary.

Some bonus reflections – if you’re familiar with online bookmarking services like Digg and Reddit you’ll know that they are full of atheists who like to post, share, and comment on articles relating to atheism. There is almost no Christian presence (that I’ve found here). Christians need to come to terms with discourse on the Internet – because it’s, like it or not, a form of community. And a nexus for people looking to discuss new ideas. Sending people in to these forums “solo” doesn’t work. Constructive conversations in this format need more than a lone voice. I don’t know how you arrange a “team” approach – but that might be worthwhile.

If you’re an atheist who arrives here and thinks “these claims are all generalisations with no substantiation” – I can, if requested, point you to different threads (mostly on my blog, on the Friendly Atheist and on Pharyngula) where situations have arisen. Here’s one example, with a follow up, here’s a post I wrote that created quite a lot of atheistic consternation, and the response on Pharyngula. Or check out guest poster Dave’s three fantastic posts on why he’s not an atheist…

- Why I’m not an Atheist #1 – Because my Parents weren’t

- Why I’m not an atheist #2 – Scientific Naturalism is powerful, but not enough.

- Why I’m not an Atheist #3 – Jesus

I’m not giving up arguing online – though I won’t spend as much time and I’ll try to establish my commitment to arguments early in the discussion, but I’d much rather chat over a beer in a pub where there’s not the ability to hide behind a computer screen and thousands of kilometres. Non verbal communication is important. And it’s much harder to be nasty to a person if they’re right in front of you (incidentally this is why you should always do radio interviews in studio rather than over the phone).

UPDATE: Hermant from the Friendly Atheist has kindly responded to my list. I’ve posted a response to his response in the comments on his blog.

I’d also like to make a small amendment to point 4 – atheists (as a general rule – not all atheists) also pay no regards to “medium” a blog entry is to be deconstructed, analysed and critiqued the same way a scientific hypothesis or peer reviewed journal is. They disagree with a sentence without paying any regard to the paragraph it builds. They interpret things they disagree with at extremes – for example – I put quotation marks around the word “Christian” above as a shorthand way of describing those who take the Christian label (making no actual judgment on whether they are Christian or not – I think you can be a Christian and be very wrong about things). And it is interpreted in the following manner:

“Oh, and putting Christian in smarmy little “scare quotes” whenever you’re using it to describe a person whose actions you disapprove of? That’s what we call a “cop out.” The claim that YOUR interpretation of the Bible is flawlessly correct and that ANY judgment you make about whether a person is or is not a Christian places YOU in a position of purported omniscience. Talk about hubris!”

That might be one way to interpret such punctuation – the traditional usage is to indicate direct speech.