This was a sermon preached at City South Presbyterian in 2024. You can listen to the podcast here, or watch it on video. Some of the block quotes were on screen and summarised but have been included in full.

It has been a bit funny throwing up this graphic every week of this series — a blueprint with the idea that we inhabit space and time; a habitat. Because the Campbell family was about to move out of home. While we worked through this series we were also working on plans for our house.

Well… when I say “our house” — it’s complicated.

Families are complex, and all of us have different stories and different things we’re juggling. But for us, we’re kind of in a season of generational limbo. We don’t own our home; we hope one day to inherit it. In our circumstances, we’re in this stage of life where it’s natural to think about our own inheritance, and also what we’ll leave our kids as an inheritance — how we might care for ageing parents, and how we’ll help our kids navigate a housing market (or make space for them). And all that gets folded into planning a renovation.

The idea of inheritance is complicated for lots of us — not just because it always involves death: the death of someone we love, or our own. It’s complicated whether we’re thinking about stewarding intergenerational wealth from a family system that has built and benefited from intergenerational advantage — and doing that with generosity and justice and love, battling temptations towards greed — or if we’ve already inherited all we’re going to get from our parents, materially or in the form of baggage we carry. Or whether we’re at the stage of life where we’re really deciding what it is we want to leave behind.

This whole question of inheritance challenges some of the way we want to think about — or not think about — time.

One of our challenges as a family — and maybe as a culture — is this sense of living moment to moment; paycheck to paycheck. Whether that’s because we’re in a sort of hand-to-mouth season in a cost-of-living crisis, or just swept up in an age of instant gratification… to stop and think longer term — about what we’ll inherit or leave behind — is not something everyone has the privilege to do.

So much of our habitat — our environment — is set up to have us live in time moment to moment, or to keep us there while others get rich.

This isn’t new. There’s a book from the 70s — Future Shock — that described a society-wide shift into an era of temporary products made by temporary methods to serve temporary needs. Future Shock is the changing experience of time caused by this super-fast change in environment — society and culture. Some of us lived through this moment… and then things got faster:

“We are moving swiftly into the era of the temporary product, made by temporary methods, to serve temporary needs… Future shock is a time phenomenon, a product of the greatly accelerated rate of change in society.“ — Future Shock, Alvin Toffler

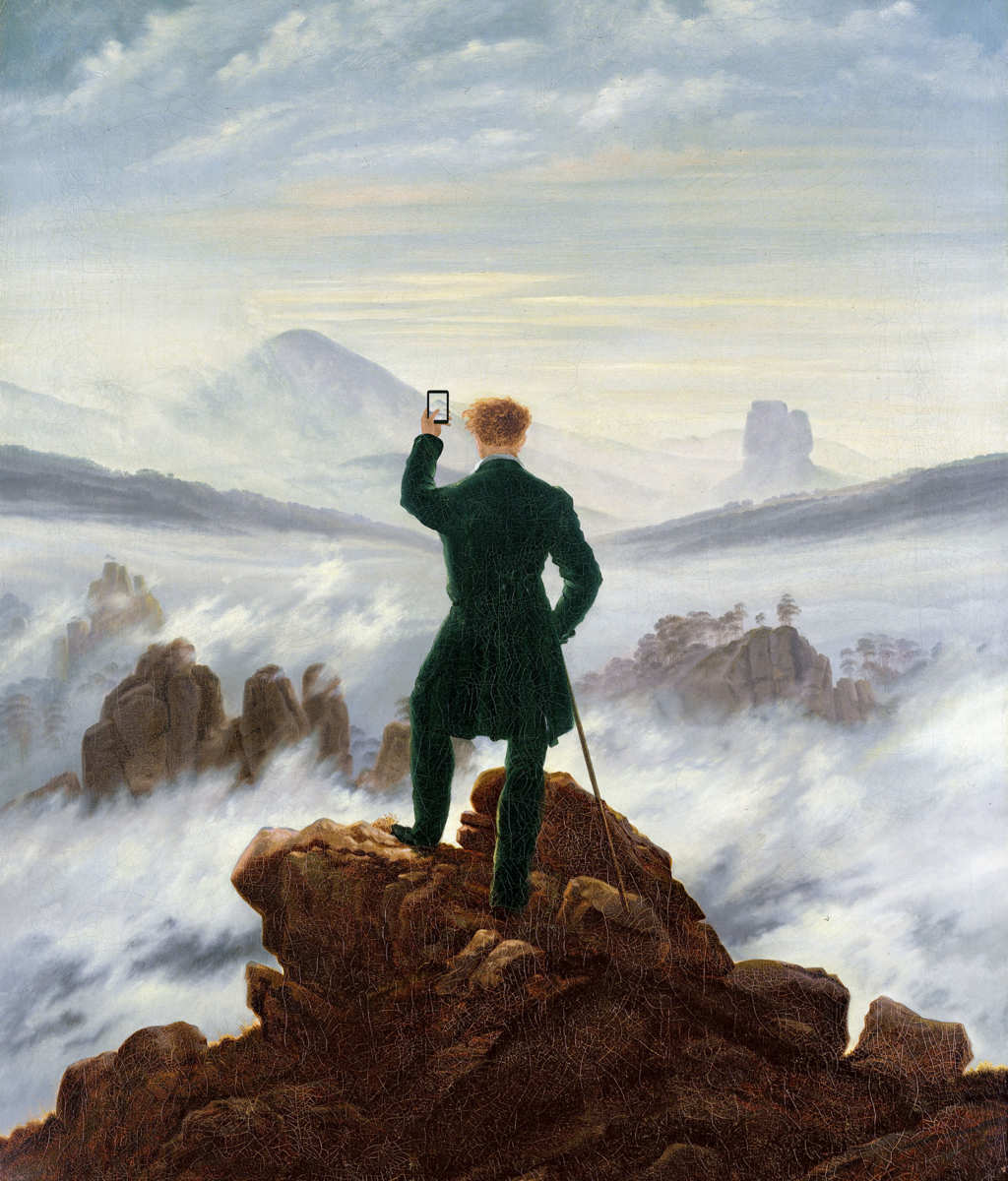

So a more recent book, Present Shock, says we now live in this constant state of being pulled in every direction all at once, in one moment. Future Shock was about one big change; Present Shock is about everything changing all the time to keep us fixated on right now.

“Our society has reoriented itself to the present moment. Everything is live, real time, and always-on… It’s not a mere speeding up… It’s more of a diminishment of anything that isn’t happening right now.” — Present Shock, Douglas Rushkoff

In present shock we don’t plan for the future or think long term, or about our inheritance — unless, like the prodigal son, we want it now so we can live fast.

Some of us, though, resist this pull. We think obsessively about what we’ll leave behind for our heirs — our super balance. We’re storing up security; wealth — delaying gratification — avocado on toast — to build something for ourselves, or for others.

Whichever camp you’re in, it’s like we’re in the marshmallow test. Have you seen this test? You put a marshmallow in front of a kid and tell them if they wait until you get back, you’ll give them another one. It was meant to be this test to show that delayed gratification leads to success… and it appeared to. This is what you might’ve heard about it.

When later scientists tried to replicate the test and actually asked the kids who grabbed the marshmallow why they didn’t wait, it turned out rich kids would delay gratification because their parents had demonstrated that adults could be trusted. While kids from poor families had learned it was rational to seize an opportunity that might not come again. And the positive outcomes for the kids in the first experiment wasn’t so much about wisdom and delayed gratification, but about what they were inheriting from their family.

If these better outcomes come from generation after generation delaying gratification and passing on opportunities and advantage… then just focusing on the present feels unwise — we’re kind of stuck. Especially when we’re also spending our kids’ inheritance when it comes to natural resources and the climate; pushing us to think really long term — sometimes in ways that distract us from needs in the present.

So how are we meant to live beyond the moment, with the long term in view?

We’ve thought about inhabiting our days and weeks and seasons. How do we expand our horizons to the bigger picture, and think about generations — and leaving an inheritance worth something for those we love? No matter what we inherit from our families, what kind of inheritance do we want to pass on to our heirs, whether they’re biological or spiritual?

I reckon we find some guides for long-term thinking in our two readings that shape how we live in the world in the present.

The sons of Korah in Psalm 49 have advice for both the rich — those inheriting and leaving an inheritance of material value — and the poor; those who’ve inherited forms of economic disadvantage. Wisdom for everyone who’ll listen (Psalm 49:1–4).

The Psalm kind of expects those who are wealthy to be wealthy through exploitation; that they’re wicked deceivers (Psalm 49:5–6). Now, this is complex, right? Wealth can be a blessing that follows wise life in God’s world. Intergenerational wealth and privilege is tricky to track — in my family history there are fortunes lost and found, and made through the colonial project here in Australia. But the Psalmist doesn’t have much patience with the idea we should trust wealthy folks who boast in their great riches in evil days; certainly not that we should fear or revere them as though they’ve got something to offer.

Because the reality is: we all die. Basically.

Their wealth can’t buy you out of the grave. They can’t go to God and ransom you — or themselves. There’s no payment, this Psalmist reckons, that’s enough to get a life out of the grave so someone can live forever (Psalm 49:7–9). Nothing the rich can do. The wise die. And so do rich fools — leaving their wealth to others (Psalm 49:10). And this sort of inheritance doesn’t lead anywhere good; it’s a speck in space and time.

We might worry heaps about how big and flash our houses are, but we’ll spend much more time dead and housed in our tombs — and his point’s not to buy a good grave or coffin (Psalm 49:11). No matter how significant we are — we could have a city or a street named after us — but we still die. Just like the beasts (Psalm 49:12). This is all very Ecclesiastes. Except the Psalm has a little upbeat note: the rich can’t ransom us from the grave and give us eternity, but the sons of Korah are confident that God can, and will. That he will redeem people from the grave and take them to himself (Psalm 49:15).

And the wise who hear this advice bring this perspective to life — a different sort of long-term vision — so we don’t get overawed by others growing rich (Psalm 49:16). And presumably the assumption is just that we aren’t going to spend our lives pursuing that sort of wealth if we know we can’t take it with us. Pursuing wealth without this understanding is pointless. As the Psalm says, we can all see everyone dies, and what we amass in our lifetime we leave to others.

So the question’s not just what do you want to live for, but what do you want to pass on? What do you want to leave behind?

Is it just that we want to pass on more wealth and comfort to a generation who might benefit — might get a better job if they don’t take the marshmallow, might have a nicer house — but they too will end up not taking it with them; our heirs will also end up in the grave.

So maybe we should be passing on something else.

Something that lasts.

To people who’ll last.

When Jesus teaches this same sort of wisdom in the Sermon on the Mount, he says, “Don’t store up treasures for yourselves on earth.” You can’t take that stuff with you; it’ll die, or break, or get stolen. But instead, store up treasures in heaven — permanent stuff — and where our treasure is, there our hearts will be also (Matthew 6:19–20).

This is a long-term investment strategy. If we can’t buy our way to eternal life, it makes sense to invest with the one who can. And there’s something about becoming a disciple of Jesus that’s about investing in others — passing on an inheritance in his family, in our households.

Which is what we see in Paul’s letter to Titus. This letter’s a lot like 1 Timothy, which we read earlier in the series — there are some overlaps.

Check out how Paul describes himself at the start of the letter: a servant of God — a slave, even — and an apostle of Jesus. He’s invested to further the faith of God’s elect — his ransomed people he’s bringing to himself (Titus 1:1–2).

Paul’s investing in people knowing the truth that leads to godliness — to the sort of life we’re looking to live as we inhabit time and space as God’s people — “in the hope of eternal life.” This is a time idea. He’s not writing to people just to keep them fixed in the present, but to keep our eyes on the long term in ways that shape how we live in the present.

He says God — who doesn’t lie — promised this eternal life before the beginning of time, and in this appointed season — another time word — he has brought to light this promise and its fulfilment through Paul’s preaching (Titus 1:2–3). Just think about what Paul’s saying about time and its meaning here: before the beginning of time, God planned to give eternal life to people. Paul’s kind of saying that to make sense of all time, we have to keep this long term in view, and act accordingly in the moment.

He’s writing — like with Timothy — to someone he considers family; his son in the faith (Titus 1:4). He’s given Titus a job in Crete: to appoint elders — leaders of the church — specifically “managers of God’s household.” We saw in Timothy this was about spiritual parents: people who shape the inheritance left to a household, and steward what has already been inherited.

And just remember — because it’s fun — when we see the word “household” in the Greek, especially with this idea of managing, we should think “economy.” Paul wants Titus to appoint leaders who’ll manage time and space and build and pass on an inheritance that isn’t about treasures on earth, but eternal life (Titus 1:5–7). The managers of this economy — the parents in the household — are to steward resources differently. Paul lists these values or virtues to be passed on: don’t be overbearing, or violently angry, or drunk, or greedy for wealth that comes dishonestly. Instead, wealth and homes are made for sharing in hospitality; as folks cultivate love for what is good — self-control — the ability to delay gratification, or choose not to be gratified but to be holy, upright… disciplined (Titus 1:7–8).

Titus has a job: he’s to teach what actions are appropriate to sound doctrine (Titus 2:1). And look, this passage is full of head-scratching moments, and we’re barely going to touch on them — and I’m sorry. I’ll do my best not to leave stuff hanging in ways that trouble you. But we’re glossing over some of the substance to see the nature of the relationships — what people are doing for each other here with the long term in mind.

Paul’s expecting older folks to create an inheritance with the long-term view in mind: passing on treasures in heaven to younger folks while they’re alive — not amassing wealth or passing it on, but cultivating godliness and loving relationships — joyful connection with God and each other — as the basis of privilege and advantage in God’s economy.

So “elder men” are to be temperate, worthy of respect, self-controlled, sound in faith, in love and in endurance (Titus 2:2). In the same way, “elder women” are to be reverent — living towards God — not being slanderers, or drunk, like the overseers in chapter 1, but to have self-control and teach what is good. They’re to pass this on to the younger generation: teaching younger women — if they’re married — to love their husbands and children (Titus 2:3–4).

I’m in the sort of camp that thinks Paul’s envisaging way more than he lists here — a sort of network of relationships where the old invest in the young becoming godly because this is how you live with the long term — eternal life — in view. But there’s a list of ways these women might do this through their example and teaching: helping younger women to be self-controlled and pure; busy at home; kind; subject to their husbands (Titus 2:5).

Now — couple of red flags there, right? We hear “busy at home” and think “oppression.” But in the first century, households were family businesses — economies. This isn’t about dishes; it’s about contribution to the shape of the household. And being subject to their husbands has to be read with everything Paul says about mutual love and respect, and wives and husbands belonging to each other, and the call for husbands not to be violent and domineering patriarchs, but those who lay down their lives like Jesus does rather than raising their hands and ruling harshly.

But I want you to see the pattern of relationships more than the content: experienced women of character investing in younger women. And the purpose of these particular behaviours is that nobody looking on will malign the word of God (Titus 2:6). It’s part of bearing witness to the world that this economy is different, because we’re living with a different vision of death and the future.

Titus and the elder men are to do the same with younger men: encouraging them to be self-controlled — to delay gratification; choosing the eternal over the momentary; eternal life over the marshmallow. Setting an example by doing what is good; showing integrity and seriousness and soundness of speech that can’t be condemned (Titus 2:6–8). Again, especially so opponents outside the church will be ashamed because their way of life is so visibly good:

“…so that those who oppose you may be ashamed because they have nothing bad to say about us.” — Titus 2:8

This is all a sort of picture of apprenticeship within this household structure: this community embracing a different economy — building an inheritance that will be passed on from generation to generation.

They’re thinking big picture, but the response is to do the hard work in their own lives of cultivating goodness and virtue — godliness — in order to pass it on through relationships. They’re not driven to abstraction, but to the very concrete.

There’s another really tricky bit here: slavery in the first century isn’t the slavery we picture in America or the British empire. It’s not that it wasn’t awful for many slaves, but slaves were part of households — often part of the family. Paul’s also called himself a slave of God. In these newly ordered households, as the economy is upended, there are ways Paul’s encouraging slaves to live with the heads of their households — again, super uncomfortable for us.

But what’s Paul doing? Telling them not to play the short-term game — stealing, instant gratification — but building trust, again so that their witness to God our saviour will be attractive (Titus 2:9–10). There’s a different view of this short-term pain and indignity that comes if a person has become an heir to God’s promises and you’re banking up treasures in heaven.

This long-term view — this vision of the grace of God — the perspective on time that comes with eternal life — God offering salvation to all people — Paul reckons this teaches us, over time. And with these examples, as people invest in us, over time we learn to say no to ungodliness, to worldly patterns and instant gratification, and instead to live self-controlled, upright, and godly lives — the lives modelled by our spiritual parents; the lives we inherit from those passing them on living with the same vision of time — while we wait for the future, the long term, to become the present when Jesus returns (Titus 2:11–13).

Jesus, who did give himself for us to redeem us and purify us as a people who are his own — people eager to do what is good (Titus 2:14). No one can redeem the life of another or give them eternal life using our own wealth (Psalm 49:7). That’s beyond what money can buy; the things of earth can’t deliver.

But Jesus does.

And he invites us into a new economy with a new sort of inheritance.

It’s lovely to be able to meet the material needs of your heirs, your household — both biological and spiritual. What a privilege it is to give and receive generosity and hospitality and security. But like the Psalm says, wisdom comes in investing in the long term. Like Jesus says, wisdom is found in storing up treasures in heaven — and we do this by helping one another become more heavenly; more like Jesus. Because it’s the bits of us that become godly that’ll last for eternity, as all else gets left in the grave.

In the next chapter of Titus, Paul says God has brought us into this life — saving us through the washing of rebirth and the renewal of the Holy Spirit. God, our heavenly Father, poured this out on us generously through Jesus Christ our saviour (Titus 3:5–6). Having been justified by his grace, this gift — this is our inheritance — we now have life with him; eternal life (Titus 3:6–7). This is our view of the long term, and what we’re invited to receive from each other and pass on to each other as something of great value.

This view of the long term, Paul says, is meant to see us carefully devoting ourselves to doing what is good — this is the economy of God; the pattern of his household (Titus 3:8). Life with the long term in view is about cultivating this goodness and hope, this inheritance that is our gift through Jesus, and passing it on.

We can get distracted by marshmallows; by wealth; by visions of the long term that pull us away from those around us — by the idea that security comes in the form of a bigger house, and that love looks like passing on wealth and advantage to those we choose to give it to.

But if you’ve found life in Jesus, you’re now part of a family who inherit this life together, and you’re invited to pass it on from generation to generation — to become the sort of person, bit by bit, who has something to give.

This long-term view means carefully devoting yourself to doing what is good — modelling that, teaching that, generation to generation. I reckon churches can get obsessed with quick fixes and fast growth — especially pastors. We hunt for silver bullets and want to see hundreds of converts, which would be amazing. But wanting hundreds of disciples, not just converts, requires something different in this model. It requires households of people committed to modelling and forming and practising and passing on an inheritance of this sort of godliness.

One of the things I love about the church of Christ is the idea that some of you have been in community for longer than I’ve been alive. I’d love our church community to think long term rather than short term about our mission — to imagine not just hundreds of people joining us, and us having to plant new things or do things differently — but to imagine little Hazel Jean, the newest member of our family, born last week, and the other newborns and toddlers and kids and teens. Imagine still being connected to them in five years, ten years, twenty years, fifty years — as older, wiser family in Jesus — invested in them inheriting eternal life.

This is the new economy — the new family — we’re invited into, where we get to both create an inheritance we leave for this generation and those that follow, and to learn to live in our own inheritance: the security of eternal life that has been given for us.

If you’re a parent, imagine this being the inheritance you’re building for your own kids — that this is a bigger and better investment than real estate or a bank balance.

Whoever you are, this is the most important inheritance passed on to you that you will steward. It produces bigger and longer-lasting advantages than the sort of wealth that means your kid will ace the marshmallow test.

What changes in the way we think about church and relationships if we think about the long term together and start living, loving, and relating to each other remembering we’ll spend eternity together?

How might this sort of time scale shape your rule of life; your practices; and the way you’re depositing into their lives in ways that’ll hopefully compound and produce something better than wealth that we can’t take with us?