This is an adaptation of the seventh talk from a 2022 sermon series — you can listen to it as a podcast here, or watch it on video. It’s not unhelpful to think of this series as a ‘book’ preached chapter by chapter. And, a note — there are lots of pull quotes from various sources in these posts that were presented as slides in the sermons, but not read out in the recordings.

We have done a few “go back in time” exercises so far; this time I want you to imagine yourself in some present-day places — and I’ll use photos to help — I want you to imagine you’re in Paris, at the airport.

This shouldn’t be hard, because all airports look the same; there are certain architectural features — like check-in desks, security, and those arrival and departure boards that are basically the same.

Which means the airport looks the same in London.

And in Brisbane.

It is the same with train stations… Paris

Looks like London…

Except for the bears…

Looks like Sydney…

Supermarkets also look the same everywhere — France…

… England…

Australia… in a global market you will even find the same brands everywhere you go.

And then there is the Swedish embassy… IKEA. Which looks the same in Stockholm, in London, and in Brisbane…

Have you thought about the architecture of these places; what they do to us? Whether that is the places we go to go somewhere else that all look the same — airports… train stations… or the places we go to consume — to buy?

Even if you haven’t — others have — very deliberately. What about the shopping centre? Like Garden City…

The first ever shopping centre was created by the architect Victor Gruen as somewhere people would go to lose themselves in the bright lights and the indoor gardens with fountains and the mazey design, while finding themselves through buying stuff.

The exact moment that you lose yourself and start buying things you didn’t really want is called the Gruen Transfer; it is where you reach what is called “scripted disorientation” — you have lost yourself, but you are following someone else’s script.

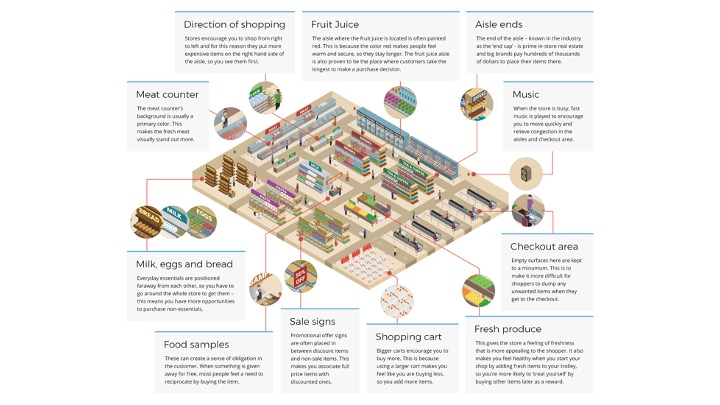

Disorienting scripts shape the layout of the supermarket; like how at the shops the milk is up the back, so you have to go through the chocolate or biscuit aisle to get there. Even where things are put on shelves and what is at eye level is calculated to make you spend more…

IKEA is built as a maze, so you have to walk through the showroom maze, and then the buying maze, walking past stacks of stuff you weren’t going to buy…

This is choice architecture — a deliberate shaping of consumer habitats to shape our consumer habits so we will buy more.

The philosopher Matthew Crawford wrote a book, The World Beyond Your Head, showing how spaces are shaped to sell us stuff by grabbing our attention.

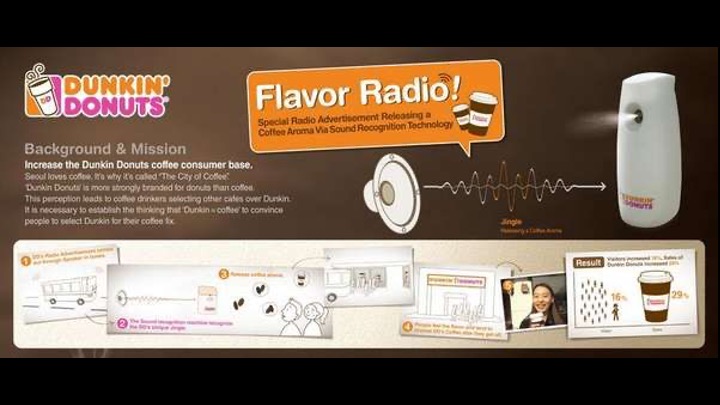

He tells two stories — one from Korea, which is kind of “in the future” for us — where buses come equipped with “flavour radios” that pump the smell of Dunkin’ Donuts into the bus, as an ad for donuts plays over the speaker, as the bus pulls up outside Dunkin’ Donuts…

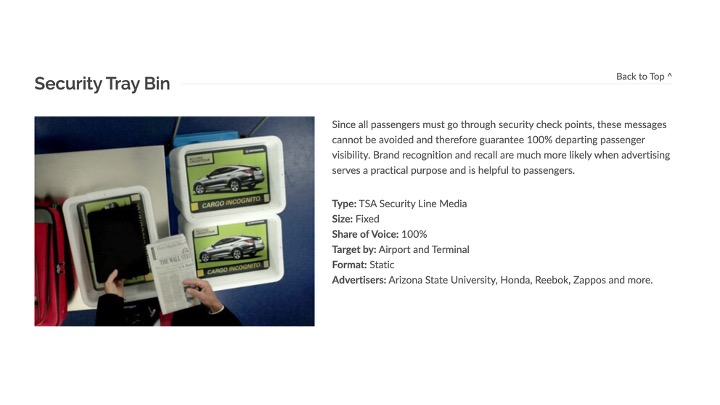

And he talks about airports — this picture is from the site selling advertising space at the Brisbane Airport — where every space is covered with advertising — even the security trays — and your attention is demanded at every turn by people selling stuff…

That is, unless you pay for silence in the corporate lounge; where the sorts of people who create the habitats where our consumer habits are formed as we are bombarded with noise, pay for silence so their attention is free from distraction.

Crawford reckons our attention is our most valuable commodity.

“I would like to offer the concept of an attentional commons… Attention is the thing that is most one’s own: in the normal course of things, we choose what to pay attention to, and in a very real sense this determines what is real for us.”

Matthew Crawford, The World Beyond Your Head

He reckons we should create an attentional commons — we should see public space as common space for the common good and cut out advertising noise so we are able to pay attention and not be scripted and disoriented in public spaces like we are in shops. He makes a distinction between nudges — made famous by this book — and jigs…

“In general, when we are faced with an array of choices, how we choose depends very much on how those choices are presented to us (to the point that we will choose against our own best interests if the framing nudges us that way).”

Crawford

Nudges operate below the surface, framing how we approach decisions — like an IKEA floorplan — so we think we have decided ourselves. They can be good if they point us to things that are good for us.

Jigs are how we set up our environments to produce the actions we want — like a carpenter who uses jigs to make repeat cuts, or a chef who has set up their workstation just right for their task.

“A jig is a device or procedure that guides a repeated action by constraining the environment in such a way as to make the action go smoothly, the same each time, without his having to think about it.”

Crawford

And if character is stamped on us by repeated action — jigs make character-forming actions easier.

“The word ‘character’ comes from a Greek word that means ‘stamp.’ Character, in the original view, is something that is stamped upon you by experience, and your history of responding to various kinds of experience…”

Crawford

If we want to build character we might choose to shape our habitats to produce the habits we desire, or other people will do it for us. Because we are matter in space; spaces matter.

This French philosopher Marc Augé describes most spaces in modern cities as non-places. Places — he says — have three characteristics.

“Places have at least three characteristics in common. People want them to be places of identity, of relations and of history.”

Marc Augé, Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Super-Modernity

They are where we go to understand and perform our identity; to relate to a community, and to be connected to history — to a shared past, and a shared story.

Architects of places deliberately structure them so people can act according to these characteristics.

Churches in medieval villages were places like this; they were cross-shaped buildings, with a steeple reaching up to heaven; they would host festivals and saint days and inside there would be a pulpit, where a story was preached, and stained-glass windows and art telling stories.

You would receive communion, with your community; while the graves of dead people from the church would be just outside.

Going to church meant participating in that place; that story; with those people — living and dead. It was not just to create roots, but grow from roots created by others… And there is something pretty cool for us City South folks about the relationship our Church of Christ family have with this space, and a privilege we might grow into as we share this space and cultivate life in it together.

Church spaces were once at the centre of city life; but now — well, they are still there — just surrounded by transport hubs and places of commerce and outdoor advertising. City squares are now non-places.

Non-places are the opposite of places — they are fast-paced places where we do not belong but move through as transient anonymous individuals.

“A space which cannot be defined as relational, or historical, or concerned with identity will be a non-place.”

“The real non-places of supermodernity are the ones we inhabit when we are driving down the motorway, wandering through the supermarket or sitting in an airport lounge waiting for the next flight.”

Marc Augé

The spaces we enter as driver, or consumer, or passenger — they are spaces where we are bombarded with advertising imagery that reinforces transience in the place of transcendence. Augé reckons they are inherently narcissistic, and they leave us simultaneously “always, and never, at home…”

We increasingly do not live where we are born, around familiar landmarks and people; we will not be buried in a graveyard next to our churches… we spend so much time in transient non-places; we live as pilgrims or exiles; disconnected from place and community and history.

Home is where we feel understood and known and connected, but transient people in non-places can feel home because they are familiar. If you are a traveller feeling disoriented in a foreign country, being in your car as an individual on a motorway, or walking through big stores — IKEAs — or staying in familiar hotel chains…

“But that we encounter the world as travellers creates a ‘paradox of non-place’ — where ‘a foreigner lost in a country he does not know can feel at home there only in the anonymity of motorways, service stations, big stores, or hotel chains.’”

Auge

Shopping and seeing brands you know can feel like a relief; these act like landmarks giving us a sense of connection…

“But that we encounter the world as travellers creates a ‘paradox of non-place’ — where ‘a foreigner lost in a country he does not know can feel at home there only in the anonymity of motorways, service stations, big stores, or hotel chains.’”

Victor Gruen’s original vision for shopping centres was a response to non-places — he wanted to create hubs where people could live and work and play locally — he hated cars and roads, which he called:

“avenues of horror, flanked by the greatest collection of vulgarity — billboards, motels, gas stations, shanties, car lots, miscellaneous industrial equipment, hot dog stands, wayside stores — ever collected by mankind.”

In other words, non-places. When his vision was not realised he moved back to Vienna, where a brand new shopping centre was being built… he had created a giant shopping machine…

“My creation wasn’t intended to create a giant shopping machine. I am devastated…”

Victor Gruen

He said he wanted to make America more like the village he had left, but had made Vienna more like America. He wanted the end of the shopping centre.

“I invented the shopping mall to make America more like Vienna and now I ended up making Vienna more like America. I hope all shopping malls end up neglected, abandoned and forgotten.”

Gruen

But now they are everywhere — as churches have moved to the margins, we have shopping centres. And as the theologian Jamie Smith points out; shopping centres function as temples; offering visions of the good life complete with routines and liturgies and priestly salespeople. Now — I just want to throw one other sort of physical space in the mix — another modern temple to the gods of fortune; the casino.

Casinos are designed to disorient… and worse — Natasha Dow Schüll wrote this book about modern gambling called Addiction by Design. She compares common places designed to build community rhythms and practices with casinos. One design style is wide and open and well lit.

“While modernist buildings sought to facilitate communitas through high ceilings, wide open space, bountiful lighting and windows, and a minimalist, uncluttered aesthetic…”

Natasha Dow Schüll

While casinos are designed with low ceilings, and maze-like layouts that direct your gaze, and your body, to the gambling machines; they are designed to keep you anonymous and disconnected.

“…casinos’ low, immersive interiors, blurry spatial boundaries, and mazes of alcoves accommodated ‘crowds of anonymous individuals without explicit connection with each other.’”

Schüll

They are lit in certain ways, and have no clocks, so that you will be disoriented — or rather — oriented towards the machines. There is a script for this disorientation.

“The intricate maze under the low ceiling never connects with the outside light or outside space. This disorients the occupant in space and time. One loses track of where one is and when it is.”

Schüll

She quotes Vegas heavyweight Bill Friedman’s book called Designing Casinos to Dominate the Competition, which proudly describes the purpose of the maze as being to confuse and confound; to get people lost so they will give themselves to the machines:

“The term maze is appropriate… it comes from the words to confuse or to confound and defines it as ‘an intricate, usually confusing network of interconnecting pathways, as in garden; a labyrinth… If a visitor has a propensity to gamble, the maze layout will evoke it.’”

Bill Friedman, Designing Casinos to Dominate the Competition

This sort of thing should make us angry. I reckon. It is also the same strategy that drives IKEA, except their maze gets you to buy Scandi furniture and homewares. But there is a new strategy in casino design competing with Friedman’s design — where rooms are open, and well lit, and beautiful… one where a guy named Roger Thomas sees himself not as an “architect” but as an “evoca-tect” — he wants to make rooms that will delight and excite; so that people will spend money.

“My job is to create excitement and delight — a task I’ve come to call evoca-tecture.”

“People tend to take on the characteristics of a room, they feel glamorous in a glamorous space and rich in a rich space. And who doesn’t want to feel rich?”

Roger Thomas

He says people take on the characteristics of a room — our habitats shape our habits, in part, by evoking our desires, and this has become a more popular design strategy — and you can bet the super-casino and lifestyle precinct built on our river will look more like this; while the pokie room at your local club will look more like Friedman’s… but what they will have in common is that the architecture is designed to take your money, and so are the machines… they are designed to disorient and addict and destroy…

Natasha Dow Schüll describes how designers adapt their machines to “fit the player” to make more money as gamblers will “play to extinction.”

“The more you manage to tweak and customize your machines to fit the player, the more they play to extinction; it translates into a dramatic increase in revenue.”

Schüll

This means playing till they run out of money; but it is a bit more sinister; talking about the use of the terminology by a speaker at a conference for pokie design, she said:

“The point of ‘extinction’ to which she referred is the point at which player funds run out. The operational logic of the machine is programmed in such a way as to keep the gambler seated until that end—the point of ‘extinction.’”

Schüll

They are designed to keep people on the machine till they absolutely have to leave, like those stories of video gamers who play so long they die at their keyboards… these machines are calibrated to needs, longings, and the pleasure receptors in our brains to pull people out of space and time — their bodies — addicts describe entering a zone where any sense of existence outside the machine disappears.

“Instead, the solitary, absorptive activity can suspend time, space, monetary value, social roles, and sometimes even one’s very sense of existence. ‘You can erase it all at the machines — you can even erase yourself.’”

Schüll

This sort of manipulation of the vulnerable should make us feel angry. Only, these same addiction mechanics are being used in our digital devices — not just by gambling apps, but by games for kids — and adults — with in-built micro-reward mechanisms that trigger exactly the same part of the brain — and Schüll says social media companies too — anyone making algorithms to keep your eyes hooked, and your hands active — people setting up the devices we carry with us to create the same scripted disorientation — the Gruen Transfer — everywhere we go — so they can make money from our addictions.

“Facebook, Twitter and other companies use methods similar to the gambling industry to keep users on their sites. In the online economy, revenue is a function of continuous consumer attention — which is measured in clicks and time spent.”

Schüll

Dr Anna Lembke wrote Dopamine Nation about how addiction works in our brain chemistry — she describes our phones as needles operating 24-7 to deliver digital dopamine.

“The smartphone is the modern-day hypodermic needle, delivering digital dopamine 24/7 for a wired generation. The world now offers a full complement of digital drugs… these include online pornography, gambling, and video games.”

Dr Anna Lembke, Dopamine Nation

She describes our apps — games, social media, gambling, and porn — even shopping — as drugs geared towards addicting us; hooking our brains on dopamine — the pleasure chemical — and leaving us wanting more. And more.

She talks about a dopamine economy — or what this other guy David Courtwright, who wrote The Age of Addiction, calls limbic capitalism — where a system is built and propped up by government and industry and technology — to capitalise on chemically hooking our brains — our limbic system, where dopamine works — by stimulating us in targeted ways geared towards excessive consumption, and then addiction.

“Limbic capitalism refers to a technologically advanced but socially regressive business system in which global industries, often with the help of complicit governments encourage excessive consumption and addiction.”

David Courtwright, The Age of Addiction

His book is terrifying; it suggests like the pokie-machine player, we are working towards “extinction by design.” And if this is true, how can we ever feel at home in a world; in spaces; geared towards our extinction?

Especially if these forces are at work in our homes; Aussie academic Adam Alter wrote about why we are irresistibly addicted to technology; he reckons we are wired for addiction and disposed towards consuming — some more than others — and this is also wired into the technology we build into our lives — our spaces — in ways that reinforce our wiring. Addiction is an inevitable product of the places — environments — we occupy, including the technology we use.

“In truth, addiction is produced largely by environment and circumstance… A well-designed environment encourages good habits and healthy behavior; the wrong environment brings excess and — at the extremes — behavioral addiction.”

Adam Alter

He reckons well-designed environments are the key to good habits and healthy behaviour; to avoiding addiction, which he says is not about lacking willpower in crunch moments — if we are already nudged towards the habit, or hooked on it — one of the keys is avoiding temptation in the first place through how we have built our spaces…

“This contradicts the myth that we fail to break addictive habits because we lack willpower. In truth, it’s the people who are forced to exercise willpower who fall first. Those who avoid temptation in the first place tend to do much better.”

Alter

This starts at home. Our habitats shape our habits; we are made to be at home in our bodies, and in places that form us. And it turns out the more our attention is pulled out of physical places into digital non-places, where we engage as viewers, browsers, and users — the more homeless we feel. The evidence is stacking up that digital non-places make us lonely — disconnected — exiled — and narcissistic. Online spaces like Amazon and Facebook are like pokie machines; designed to pull us in; our experience is shaped by algorithms that are scripted to adapt the machine to us, while our dopamine-hungry brains crave bigger hits. It is a brave new world.

And maybe what is worst is when church spaces become non-places rather than sanctuaries from this world — when we copy the architecture of the shopping centre, or casino — building mega-facilities people drive to like shopping centres, where people flows and signage guide us into black-box rooms, where our attention is oriented towards screens.

And notice how all these churches end up…

looking…

… the same. Even the Presbyterian ones.

Like non-places built for transience, not transcendence.

Some of us met in buildings like this in West End — one was a theatre, one was the church building pictured in the first image — that was the pentecostal service meeting in the morning slot. Can you see how these habitats might subtly set us up to think about church as a product, or as entertainment; where our attention has to be grabbed and directed towards our desires, like at a casino, or we will leave unsatisfied? Where familiarity creates the illusion of belonging; rather than being places where family connection is cultivated and shaped by the story of the Gospel; places for us to inhabit with the people around us — those we commune with, whose faces we see — because the lights are not off — as God works in us through his word — that we can see without using a screen — and by his Spirit and his people?

The Bible does not set us up to live in non-places — but to live and interact as creatures in the created world; and even to make places in it as images of the God who creates place. Habitats for life, that prime us to engage in character-building habits.

God places Adam in a garden — a place — with fruit trees that are beautiful and good to eat (Genesis 2:8-9). Trees he’s to eat from — eating would be a habit that would teach him about God’s love; his provision; his hospitality (Genesis 2:16-17). The pleasure of seeing and eating that fruit was made to create something in our hearts as the pleasure chemicals kicked in. God created dopamine hits; they are meant to orient our hearts towards him, and each other, and so we could love and enjoy his world in ways that made us more human. To eat otherwise is to eat to extinction (Genesis 2:17). Our grasping, addictive, narcissistic hearts are the fruit of embracing sinful desire for self-satisfaction, and our self-declaration that things that are not good for us are good (Genesis 3:6). Chasing dopamine hits on our terms…

There is an interesting relationship between idolatry, desire, and place-making after Eden. Adam is placed in a place he is to cultivate and keep (Genesis 2:15) — these are space-making words. They are used for how priests are to maintain the tabernacle and temple as Eden-like spaces where God meets his people. The sanctuary — and altar — spaces that teach Israel about God (Numbers 3:7-8; 18:4, 6).

These spaces teach God’s people about God’s desire to be present and in relationship; his holiness; his grace; the shape of heaven and earth and the barrier represented by the curtain; his ongoing provision of life; even the smells and taste of meat and fruit and bread connected to sacrifices and feasts and festivals taught Israel its story in places; there are habitats jigged up to shape Israel’s habitual worship, stamping character — the image of God — on God’s priestly people.

Only Israel kept bringing idols and their rituals into their environment; they were a dopamine nation. Solomon is particularly instructive here, as a place-maker — while he builds the temple (1 Kings 8:12-13), he fails to cultivate and keep Israel as a place-space for life with God; by building high places and bringing in idols with their dopamine-inducing incense and sacrifices (1 Kings 11:7-8); the character-shaping habits of idolatry.

So Israel ends up in exile — in Babylon — with its hanging gardens and lush places and massive towers and idol temples — the whole environment of Babylon was scripted; designed; like our casinos, our scent-distributing buses, and our smartphones — to direct attention and habitual worship to their gods and king. But what does faithful life in Babylon look like? Place-making.

“Build houses and settle down; plant gardens and eat what they produce. Marry and have sons and daughters; find wives for your sons and give your daughters in marriage, so that they too may have sons and daughters. Increase in number there; do not decrease.”

Jeremiah 29:5-6

Planting their own little Edens; making spaces that are reminders of their story — of God’s hospitality, his desire for presence; that he is the source of blessing and that he calls his people to be fruitful and multiply and bless those around them — they get back in the land and rebuild their spaces, but something is missing.

And then Jesus turns up to end the exile — from Eden and Israel — as the tabernacle-in-the-flesh who brings heaven on earth — who comes to save us from homeless life in non-places — and he does not do this by restoring the temple to its former glory — as heavenly space — but his death tears the curtain, the picture of the barrier separating heaven and earth; representing our exile from Eden; from God (Matthew 27:50-51); and this does not mean that space-making is over; that suddenly we are meant to exist without habitats that shape our habits — without a temple.

Jesus makes a new temple — new tabernacles-in-the-flesh in Acts, by pouring out his Spirit on people — the church (Acts 2:33). The first church did not have cathedrals, or even church buildings. They meet in houses. Homes (Acts 2:46-47). They go to the temple, as well, in Jerusalem — but the home is the normal habitat as the church spreads into the rest of the world; and presumably there are some dopamine hits happening as they eat with glad hearts and praise God.

The home is the habitat for the Acts 2 habits — it is where they devote themselves to the apostles’ teaching, to the breaking of bread, and to prayer — meeting together (Acts 2:42). The house becomes disciple-making architecture; homes become places connected to the story of the Gospel; of God making his home with his people, who are now temples of the Holy Spirit. The shared table is a setting geared towards teaching people about hospitality; to position those around the table as members of a household — it is a picture of us now being home with God; no longer exiled, but connected to him as family. Home is the ultimate place.

Look at what Peter says in 1 Peter 2; the church — people — are chosen by God and precious to him. As we come to Jesus — the living tabernacle — we are built into a spiritual house — or temple of the Spirit — we are the holy priesthood (1 Peter 2:4-5), the new Adam, the new Levites — with the job of cultivating and keeping the space where heaven and earth come together; where we learn about God and are shaped by him as we declare the praise of the God who has re-created us for this purpose through Jesus.

Our sense of homelessness in non-places is part of our longing for home; and this longing is satisfied as God makes a home with us, promising to dwell with us in a new heavens and new earth forever (Revelation 21:2-3). Our home-life — our space-making — is now an opportunity to testify to this story. Peter describes the church both as the home of God — home with God (1 Peter 2:5), and as exiles (1 Peter 2:11)… like foreigners in Babylonian spaces and other temples that wage war against our souls.

We have a weird relationship to earthly space. We are not home. It is like every space not oriented towards heaven — the transcendent — is a non-place, oriented towards earth, and transient.

“In the world of supermodernity people are always, and never, at home.”

Marc Augé

We feel homeless in a world full of people who feel homeless; but we know where home is, and our neighbours don’t. This transient never-at-home-ness and the places built to satisfy that longing with earthly stuff — casinos and shopping-centre temples, even digital spaces — are expressions of a longing to be home with God; part of being exiled.

But we are home because God is going to renew earth and make it heavenly, and we are heavenly people who can make little embassies of heaven in anticipation… pointing to the transcendent.

Our spaces are not temples — we are the temples; the church is the people not the building — but because we are place-making humans made in the image of a place-making God, and we are formed by our habits, and our habits are formed by our habitats, our place-making is an act of worship and of cultivating the world according to our story; whether that is at home, in our workplaces, or in our public spaces — like the church. It is also an act of embassy-building for us citizens and ambassadors of heaven… as we live good lives in Babylon, navigating idol temples, while making good places.

Abstaining from sinful desires raging war against our soul (1 Peter 2:11) requires resisting scripts that want us to forget our story; the story of the Gospel by cultivating habits of saying no to Babylon; acting with deliberation where the world wants us to act like automatons.

So here are some guiding principles from all this — we have to grab control of our attention — wrestle it back from limbic capitalism and its addictive extinction machines. We have to pay attention to the scripts that are disorienting us; pulling our feet from the path — whether in the physical environments we enter, or the digital spaces we occupy and devices we use. This might even look like deliberately walking the wrong way at IKEA or the supermarket — or sticking to a list — to resist impulse buying, or blocking ads on your browser, or limiting your screen time.

Maybe we could catch the vision of the attentional commons — in the spaces we control, but also in public — there have been some Christians who have campaigned for G-rated outdoor advertising; I wonder if we should go further; fighting against the privatisation of public spaces, for the good of our neighbours, especially fighting against gambling ads. We could pay more attention to the insidious and addictive gambling industry and how entwined it is in our culture — it is not a small problem.

And we should notice how the same techniques are embedded in our culture, and our lives, through desire-shaping technology, and advocate for the regulation of online spaces and technologies in ways that limit their addictive potential, rather than participating in platforms that make us lonely and narcissistic and are designed to drive people to extinction.

We are not saved by good habits; but we are saved to become disciples who are home with God; saved to devote ourselves — and we are given new hearts, by the Spirit, and new tools to do it, and a new story. Saved to break bread together; to have glad and sincere hearts, and to praise God in ways that are recognisably good in a world facing extinction. We have got to see where we are being nudged, and push back accordingly. And one way to do this is by cultivating our own spaces with jigs that make good habits feel automatic.

Whether that means creating a spot in your house where your phone is charged that keeps it away from your pocket, or your bedroom at night — or working out how to keep good things within reach; whether that is art on your wall, or photos on your fridge prompting you to pray for others, or physical copies of your Bible close to hand, or a picture on your homescreen; or your Bible app in the shortcut bar on your phone so you have to deliberately scroll past it to get to your distractions…

We have to consider the physical architecture of our houses, and our lives; one of my big regrets in the design of our house is the way we have oriented our couch towards the TV; that fuels my gaming addiction, and makes the screen our default.

There are implications here for how we create and use public space like this building — church buildings should not be non-places, or disorienting temples to consumption that are another form of limbic capitalism; it is tricky because those temples, like the hanging gardens, are often imitation Edens.

There will be wisdom and discernment involved in avoiding designs that nudge us towards extinction; and in cultivating spaces that teach us about God and evoke our sense of his goodness; just as there is in creating communal dopamine hits that are humanising because they come from encountering God through our bodies, rather than addictive.

Whatever the future looks like for this building, or a space for our communities — we should resist creating places without stories and connection to history and to people — living and dead — and should create places where community happens… places where we do not experience scripted disorientation, but Scriptured orientation — where we point our hearts towards God together; praising him through worship; through embodied life together in space and time.

This might include us appreciating the art on the walls downstairs as a picture of the faithfulness of a previous generation, but it might also involve us collaborating on new art, and beauty, and activities that bring life to this space. This might involve us resisting a tendency towards transient nomad life or being travellers, and seeking to put down roots; in space and time — but with our eyes looking towards our eternal home. This might involve us cultivating hospitality and habits and pictures of life and generosity that flow from here — like with Food Pantry and lunch together — in ways that celebrate God’s presence with us, as temples of his Spirit, and look forward to his hospitality in the new Eden.