This is an adaptation of the tenth talk from a 2022 sermon series — you can listen to it as a podcast here, unfortunately, due to a technical error, there was no video for this week.

It’s not unhelpful to think of this series as a ‘book’ preached chapter by chapter. And, a note — there are lots of pull quotes from various sources in these posts that were presented as slides in the sermons, but not read out in the recordings.

We have put ourselves in various moments in time this series—imagining the past, and the future. This time round I want to take you all the way to the end.

How is the world going to end?

Now, of course, as Christians, we have an ending described for us in the book of Revelation. Jesus is coming; he will reward his people with life with him and the tree of life (Revelation 22:12–14). But I am wondering how much difference that ending makes in how we think about being human—and how you live.

What difference would it make to your life without that ending? If you believed every part of the Christian story to be true but there was nothing about the future—about what happens after death or at the end of the world—how would you live? If you knew God revealed himself and his character in the crucifixion, but we had no resurrection or return, would you live differently today?

You might be here this morning still not convinced about the whole Christian story. This might actually be where you are at. I am going to suggest this end makes all the difference—that it is the end of the world’s story and the human story as we know it—and this is meant to shape how we understand being human.

And just for a moment I am going to try to put us in the minds of people who do not buy that ending, using Douglas Adams’ Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy series, where in book two there is a time travel service that will take you to the restaurant at the end of the universe, so you can sit and watch the world end with a ‘Gnab gib’ — the opposite of a big bang — and go back to your life knowing that all that comes after death and after history ends is the void; oblivion. The point of this book series is to offer a deliberate guidebook to a technological world without God. He creates a galaxy to show how if life in time and space is all there is, the hunt for meaning is meaningless. It is not “42;” it turns out that is the answer to the wrong question—and the whole point of the books is pointlessness. It is to stop people looking for meaning, so that we are not crushed when we find out there is none. There is this device, a Total Perspective Vortex in the books, that shows you as a tiny dot in an infinite universe, and it crushes anyone who thinks there should be a meaning in life or the world—anyone not totally self-centred. You are better off not looking.

The ideas of the end of the world and the purpose of our lives in it are deeply integrated.

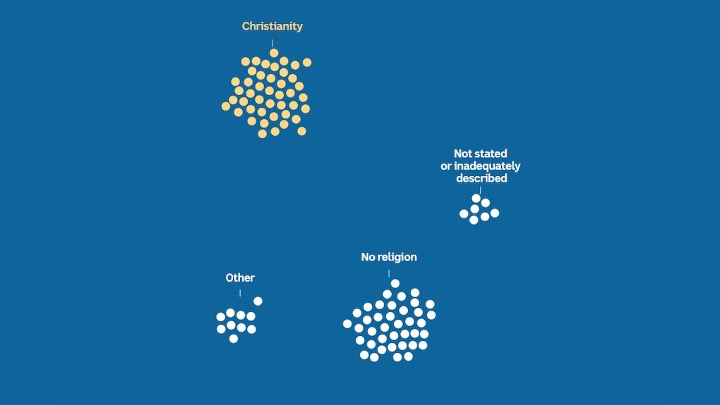

When we see the world ending with the void—or life ending with death—and no God in the picture, we are left figuring out what our own life is for; how we should use it. I reckon most of our neighbours reckon we are facing the void, or just adopting the “she’ll be right, mate” idea that everything is going to pan out. And so life in the modern, disenchanted world ends up being the expressive individualism we have talked about, where you are responsible for making your own purpose, even if that comes from connecting yourself to some bigger agenda. Adams ends up being a prophet for this disenchanted world.

In theology land the way we talk about the end of the world is with the word eschatology—it is from the Greek word for last. And the way we talk about the purpose of human life—the ends, like in “the ends justify the means”—is the Greek word telos, which means something like living towards the fulfilment of a purpose. If you are a Presbyterian and I say “the chief end of man is…” you will say “to glorify God and enjoy him forever.” That “chief end”—that is a telos. It is the built-in purpose that guides our actions.

That guy Alisdair MacIntyre, who says we are story-telling animals who “need to know what story we are living in to know how we should live, as we saw last chapter “can only answer the question ‘what am I to do?’ if I can answer the prior question ‘Of what story or stories do I find myself a part?’”; he also reckons we have been left feeling like life is meaningless because we have lost a sense that our lives are headed towards a telos. This ‘end’ or purpose for our lives came from understanding our lives as living in a story that came from beyond ourselves, that was pointed somewhere beyond ourselves, but life facing the void, where we are left trying to make meaning and find a purpose from within ourselves—maybe, like the author of Ecclesiastes suggests—that sort of life is meaningless, if it just ends in death.

“When someone complains that his or her life is meaningless, he or she is often and perhaps characteristically complaining that the narrative of their life has become unintelligible to them, that it lacks any point, any movement towards a climax or a telos.”

— Alisdair MacIntyre, After Virtue

The Christian story suggests life is not meaningless, that it has a telos. We might be inclined just to look back to our origin story, to Eden, to figure out what we are made for—and we will do that—but we have also got to look to the end of the story to find our ends. So we are going to try to hold this tension—these furious opposites—and maybe see how the Bible holds it for us, because when we integrate our lives with God’s story, its beginning and its ending, we find our telos; we find life; we find what it means to be truly human.

Back in Genesis we saw how the image of God is not just a static thing in us (Genesis 1:26); it is not just a noun that describes us; it is a verb we are made to be; a vocation. It has a telos built in—to be truly human is to rule his world, representing his rule, his kingdom.

This idea is built from what images of gods were in the ancient world, and off the work of scholars like John Walton who suggest what it meant to be something in the ancient world was not just to have material qualities, it was to belong in a system, with a function; it was to have a telos.

“People in the ancient world believed that something existed not by virtue of its material properties, but by virtue of its having a function in an ordered system.”

— John Walton

But not only is the image of God not just a static thing in us, it is not a static thing only defined in Genesis; our understanding of what it means to bear God’s image, this function, develops with the story of the Bible. We do not just look back; we work out what it looks like as we see characters breaking it; it is frustrated as people sin—falling from this function—and are exiled from God’s presence. And we see it restored, and developed, as God creates a priestly people, Israel, to represent him in the world, and then kings who are meant to be representative rulers of his image-bearing people.

And so we come to Psalm 8—which we looked at lots in our Genesis series—where we are told it is a Psalm of David; where we are told humans have been crowned with glory and honour (Psalm 8:4–5). That God made us rulers over the work of his hands; there is a Genesis 1 reference happening here (Psalm 8:6).

Now, we have this tendency to democratise the Psalms, to jump to making this about us—there are just a couple of steps I think we need to take before we do that. We can also democratise it by looking back to Genesis, but we should be careful here too.

Now, I have quoted stacks of scholars this series, and they can feel distant and overwhelming. So today I am quoting a biblical scholar who is the opposite of distant. In this article by Doug Green, our Old Testament scholar in residence (well, not quite — note for readers, Doug is an elder in our church), Doug invites us to consider that with this Psalm of David, which could be a Psalm about David, we are meant to imagine David wearing a crown like the first readers would. So these words are not so much about all humans, but the dignity and worth and glory and honour of true humanity: humans living and ruling in a way that represents God, which is Israel’s role in the world, and David’s role in Israel as the true human.

“Psalm 8 is less interested in the dignity and worth of humanity in general, and more concerned with the dignity and worth, the glory and honour, of the true humanity, Israel, and the true human, David (and his descendants).”

— Doug Green, ‘Psalm 8: What is Israel’s King, That You Remember Him’

Doug reckons the Genesis creation story works to teach Israel what true humanity looks like; how to live as replacement Adams—humans—after Adam and Eve’s failure. Israel is a new humanity, but more than that Israel’s Davidic king is presented as an image-bearing ruler.

“But this story is a background for the real focus of the Old Testament: Israel’s role as the replacement for the First Humanity of Genesis 1, and David’s role as the replacement for the First Human (Adam) described in Genesis 2 and 3.”

— Doug Green

This king will either lead people to life with God, or death and exile. And this Psalm is about someone—it could be a son of Adam—crowned with glory and honour, which is, as Doug points out, royal language.

“The Davidic king was thought to be a second Adam, Adam reborn, as it were… True Man is crowned—can you hear the royal language?—with God’s glory and honour!”

— Doug Green

Doug reckons as we read this Psalm knowing David’s failures we are meant to read it eschatologically—wondering where in the future we will meet a true human, a divine image bearer. Someone who fulfils the purpose, the telos, humans are made for.

“But once I interpret this psalm in connection with Israel and especially Israel’s king, I am now bent in an eschatological direction. The stories of Israel and David are covenantal stories and therefore stories with a telos, or destiny.”

— Doug Green

Our idea of an image bearer gets developed in contrast with the failures of would-be image bearers as we keep waiting for a true human to turn up at the climax of history.

“The primary thrust of Psalm 8 is not creational and static (what all humans are in Adam) but re-creational and eschatological (what Israel and ‘David’ will become at the climax of history).”

— Doug Green

The writer of Hebrews reads it this way too; when they quote this Psalm (Hebrews 2:6, Psalm 8:4), they say, you know we do not see this everywhere, it is not the general pattern for human life. But we do see it in Jesus, the fulfilment of this Psalm; a true image-bearing human crowned with glory and honour, because he suffered death—that is the whole cross-shaped kingdom thing from last week.

“But we do see Jesus, who was made lower than the angels for a little while, now crowned with glory and honour because he suffered death, so that by the grace of God he might taste death for everyone.”

— Hebrews 2:9

He is the Son of David, the Son of Adam, the true human image bearer, who does not fall to the powers. And he brings many sons and daughters—many true humans—with him to our glorious telos; to being able to function as those who represent God (Hebrews 2:10). The telos, the purpose of humanity, is to reflect—to radiate—God’s glory. Hebrews calls Jesus the pioneer of our salvation, made perfect—these are significant words. The word here for pioneer could be translated author in your Bible; it is this word archegos—it means first, or model, or archetype. And this word perfect—it is the word teleiosai—it is the word for fulfilling your telos; being made complete according to your purpose. Jesus is the model telos-fulfilling human, the true human, through his suffering and his resurrection, through representing God’s glory.

Hebrews will come back to these same two words when it talks about how we should live; how we should run our race towards an end, fixing our eyes on Jesus, the pioneer and perfecter (Hebrews 12:1), the model and telos-fulfiller, the true human, the new David, the new Adam, who because of the joy set before him—not because the cross revealed God’s character, but because of the glory to follow—endured the cross, and then sat down at the right hand of God, crowned and glorified.

These words come up a few more times in the New Testament. John uses these same words in our passage in Revelation, where Jesus does not just say he is the first and last and beginning and end (Revelation 22:13), but arche—the model—and the telos—the fulfilment (Revelation 22:14). And the last in verse 13 is actually eschatos; he is the fulfilment of the human—our telos—and the eschatological human who brings the new creation. He is the one the Scriptures have been waiting for since Adam.

We covered 1 Corinthians 15 earlier in the series—where Paul says the first man Adam was a living, breathing image of God, and Jesus is the last Adam, literally the eschatological Adam, who brings God’s Spirit (1 Corinthians 15:45). Those who are united to Adam, that old image, die, disintegrating into dust. But those who see the fulfilment of the image in Jesus, seeing his true humanity, those belong to him as the new David, the king—we will follow him into his glorified life, bearing his image (1 Corinthians 15:49). When we are united to Jesus, his story becomes ours—we live under his rule, waiting for our new life to be made whole; for the Spirit working to produce fruit in our mortal bodies to be matched with spiritual, immortal bodies, waiting for the defeat of the last enemy, literally the eschatological enemy: death (1 Corinthians 15:24–26). This will happen when Jesus returns to make all things new.

Living in this story—with this ending and telos—shifting from the old Adam to the new, is how we become truly human, images of God. It is how we share in his glory, which is what Paul is on about in Romans 8 (Romans 8:16–17). Our becoming truly human as we receive the Spirit and are re-created and liberated, in a way that gives our life meaning, even when we suffer.

The Spirit, Paul says, makes us heirs of God, his children, his image-bearing people who will share in the glory of Jesus. We become truly human as our telos becomes to become like Jesus, and our future is secured. And this gives meaning to our sufferings now, both as we take up our cross, following Jesus’s example (Romans 8:18–19). Suffering is not an end in itself; it is not our telos; our destiny. We might hear it said that “to be human is to suffer well,” to bear the weight of being. But to be truly human is to suffer with the hope of glory; that is our new destiny. Our suffering—whatever it is, whether it is the cost of curse, or what we experience as we follow our crucified king—is not our purpose or destiny. It is incomparably small compared to the glory that is ours as we become truly human through Jesus.

Our lives are shaped by a new image of the fulfilled human life where death leads to resurrection, and a new destiny that is not just for us, but for the world. Creation itself joins in the expectation of liberation from bondage to decay, as it is brought into the freedom and glory we are brought into (Romans 8:20–21). Just like creation itself is anticipating liberation, we live hoping for the redemption of our bodies. We live lives shaped by hope, knowing that God is working for our good, that he has called us according to his purpose—that is actually a different word to telos—that we have been chosen to be conformed to the image of his Son, to become truly human, so that Jesus might be the first of many brothers and sisters, bringing us to glory as we are conformed into his image (Romans 8:23–24, 28–29). This is the trajectory we are now on—as chosen and justified people with failures forgiven, one where we are re-created as true humans and glorified (Romans 8:30). So that Jesus’s present and future becomes ours, so in him we are more than conquerors, people who cannot be destroyed by death, or demons, or the present or future, or the powers that we have seen at work in the world. Nothing will be able to separate us from Jesus, from God’s love, from being truly human (Romans 8:37–39). Because, as Doug puts it:

“It is only as we are united to Christ and indwelt by his Spirit that we humans can claim to be bearers of the divine image, crowned with glory and honour.”

— Doug Green

Now—we are on the home stretch in this series. And here are our take-homes for today, and for the series. Being truly human means living lives integrated with God’s story. This story gives us, and the world, a telos—to be an image bearer is not simply to suffer, even as we take up our cross—it is to reflect God’s glory, to glorify God and enjoy him forever you might say. And we see this telos fulfilled in the end of our story. The Bible’s story about humanity, this story tells us who we were made to be, and what our destiny is, and invites us to be truly human. This ends, and this ending give us meaning, and the means we should employ as we become characters in God’s story.

We are not hitchhikers in the galaxy, facing oblivion at the restaurant at the end of the universe. In Jesus we are sealed, and seated at the banquet at the end of the universe, and it lasts forever. We are not insignificant, finite nothings, just made to suffer and die, but immortal and glorious and loved by God.

C.S. Lewis talks about this in his sermon The Weight of Glory. He reckons we are too quick to embrace self-denial and suffering as ends, as though that is our purpose, when we are actually made to follow Jesus into glory and to have our desires satisfied.

“The New Testament has lots to say about self-denial, but not about self-denial as an end in itself. We are told to deny ourselves and to take up our crosses in order that we may follow Christ; and nearly every description of what we shall ultimately find if we do so contains an appeal to desire.”

— Lewis, The Weight of Glory

Lewis says we need to live knowing we are not small and insignificant, but that we will outlast anything earthly. Nations, culture, art — those things that seem big and significant are tiny compared to our glorious future.

“Nations, cultures, arts, civilization—these are mortal, and their life is to ours as the life of a gnat. But it is immortals whom we joke with, work with, marry, snub, and exploit…”

— Lewis

This means it is actually other people — those with God’s Spirit — immortals — who are truly significant. We should see ourselves this way, as gloriously beloved by God, and it should change the way we see others. This capacity is in every human, and already at work in those gloriously united with Jesus.

He says that other than when we recognise Jesus in the sacrament — which is what’s happening, in his theological frame, during communion — other than the presence of Jesus in us, your neighbour is the holiest object in your life, holy in the same way as Jesus because Jesus, the glorifier and the glorified, the archetype and the telos, is hidden in them.

“Next to the Blessed Sacrament itself, your neighbour is the holiest object presented to your senses. If they are your Christian neighbour they are holy in almost the same way, for in them also Christ the glorifier and the glorified, Glory Himself, is truly hidden.”

Lewis, The Weight of Glory

But what difference does all this talk of glory make? I reckon we can be a little obsessed with still seeing ourselves as sinners — and we are — but not as those being re-created and liberated by the Spirit — which we are.

Killing our sin — what gets called mortification — is part of our transformation, but we could do more to remind ourselves that this is who we are in Jesus; holy and being made glorious and being transformed by God’s Spirit in us. We might see our new life not just as putting sin to death, but also cultivating new life, in what gets called vivification. You — if you belong to Jesus — are no longer a slave to the flesh; no longer the old Adam. You are the new Adam, and God’s Spirit is at work in you conforming you to the image of Jesus, revealing God’s glory in your life. That’s your telos, and where your story is going.

And this means our lives can be marked by hope — not just in the face of death, but hope about the future that we enact in our life now. We can see our longings — our desires — as parts of us pulling us towards our end goal.

Both C.S. Lewis and his friend Tolkien had this hope in ways that made their stories remarkably different to The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. That was disenchanted science fiction about purposeless life in a material universe that ends in the void, while Lewis and Tolkien wrote fantasy set in enchanted worlds, shot through with longing for glory. Tolkien talks about how our longings are a product of life exiled from Eden, and his stories are about finding the answer to these longings.

“Certainly there was an Eden on this very unhappy earth. We all long for it, and we are constantly glimpsing it: our whole nature… is still soaked with the sense of ‘exile’.”

— Tolkien

Lewis talks about passing beyond the natural world into the glorious splendour where we will eat from the tree of life — straight out of Revelation:

“We are summoned to pass through Nature, beyond her, into that splendour which she fitfully reflects. And in there, in beyond Nature, we shall eat of the tree of life.”

— Lewis

This is an image he evokes at the end of The Chronicles of Narnia, where the characters enter a new eternal story:

“All their life in this world and all their adventures in Narnia had only been the cover and the title page: now at last they were beginning Chapter One of the Great Story, which no one on earth has read: which goes on for ever: in which every chapter is better than the one before.”

C.S Lewis, The Last Battle

As they go further up and further in into a garden paradise:

“Further up and further in… So all of them passed in through the golden gates, into the delicious smell that blew towards them out of that garden and into the cool mixture of sunlight and shadow under the trees…”

C.S Lewis, The Last Battle

Tolkien has Frodo and the Elves sailing to a land in the west featuring white shores and beyond them a far green country under a swift sunrise. And in his brilliant short story Leaf by Niggle, he describes Niggle — a painter — finding life in the garden paradise of his painting coming to life, as he goes further and further upwards towards the mountains:

“He was going to… look at a wider sky, and walk ever further and further towards the Mountains, always uphill.”

— Tolkien, Leaf By Niggle

Both Tolkien and Lewis had more than an inkling. They understood how the end of our story should shape our desires, and their stories — like their lives — were attempts to evoke these desires in us, to pull us further up and further in. We would do well to soak our imagination in enchanted stories of hope, because this is our story.

And cultivating the hope of glory has to shape how we live as a hopeful witness to those following the old Adam towards a destiny of dust and death. Some people reckon thinking eschatologically runs the risk of having us so set on heaven we are no use on earth, but the theologian Stanley Hauerwas reckons how we see the end of the world — eschatology — is the basis for Jesus’ ethical teaching, as he calls us to our telos; our re-created purpose.

“…we mainline Protestants have charged eschatological thinking with being ‘other worldly,’ ‘escapist,’ ‘pie-in-the-sky-by-and-by’ thinking… the biblical evidence suggests that eschatology is the very basis for Jesus’ ethical teaching.”

— Stanley Hauerwas

Hauerwas says Christian ethics — how we live — is built on Jesus being the eschatological Adam, the new David, who launches God’s kingdom in the world now, and that the Sermon on the Mount describes the end of the world as it was — the world of Adam and Satan, that ends with his crucifixion and resurrection — and a new way of life, the ends we should live towards.

“There is no way to remove the eschatology of Christian ethics. We have learned that Jesus’ teaching was not first focused on his own status but on the proclamation of the inbreaking kingdom of God… In the Sermon [on the Mount] we see the end of history, an ending made most explicit and visible in the crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus… The question, in regard to the end, is not so much when? but, what? To what end?”

— Stanley Hauerwas

Hauerwas reckons living in this story makes us resident aliens, as he calls us — an adventurous and hopeful colony, a community living in a society of unbelief. In his diagnosis our culture has not just lost a telos, but a sense of adventure, because we have turned in on ourselves as we have lost this big story.

“The church exists today as resident aliens, an adventurous colony in a society of unbelief… As a society of unbelief, Western culture is devoid of a sense of journey, of adventure, because it lacks belief in much more than the cultivation of an ever-shrinking horizon of self-preservation and self-expression…”

— Stanley Hauerwas

This community, embodying and telling this story, is where Christian ethics makes sense. The world tells us being truly human is about self-expression, because this is all it is, but our eschatological messianic community tells us that to be truly human involves self-denial with our eyes fixed on the eternal rule of King Jesus, and being united to him.

This community — the church — is where we tell each other the Gospel; truthing in love.

“The ethic of Jesus thus appears to be either utterly impractical or utterly burdensome unless it is set within its proper context — an eschatological, messianic community, which knows something the world does not and structures its life accordingly… A person becomes just by imitating just persons. One way of teaching good habits is by watching good people, learning the moves, imitating the way they relate to the world.”

— Stanley Hauerwas

This community is where we find examples to imitate as we learn what a life shaped by our ends, shaped by Jesus the true human, looks like. It is where we are formed in order to be sent into the world. It is where we run the race together as we learn to fix our eyes upon Jesus.

It is hard for us to set our eyes on Jesus in a literal sense, given that he is seated in heaven. We can do that in prayer, and in what Paul calls the eyes of our heart, but we can also fix our eyes upon Jesus in a way that teaches us to be human by looking at one another, finding examples who are living in this story to imitate.

Before they say this, the writer to the Hebrews has just told the church to keep meeting together, spurring one another on, before they say run the race by fixing our eyes upon Jesus.

Part of pursuing our telos is seeking to be those who follow the example of Jesus, and this might involve watching and observing and imitating those around us who already are. Those whose lives are marked by hope, those whose lives express the fruit of the Spirit, those who are living adventurous lives of self-denial because their hearts are set on heaven, and because they know that to be truly human, in Christ, is to have conquered the powers, and anything in creation that wants to separate us from the love of God that is in Christ Jesus.

Ends.