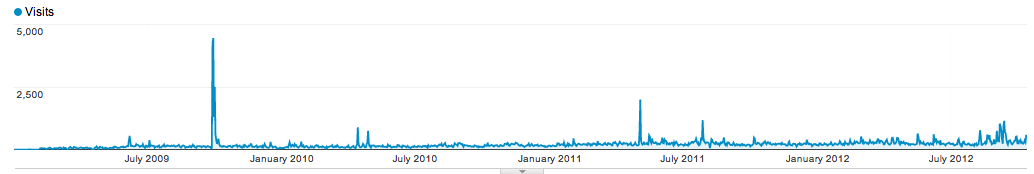

This little exercise of turning longform radio story-telling ala the internet intelligentsia’s favourite This American Life and others into a scribbles on napkins is nice. Because thinking about how to structure stories is an interesting exercise – for those who like telling stories, reading stories, or, I would argue, preaching. If a significant part of the material we preach from is narrative – and if we have a view of the Bible that sees it as one overarching and intricate narrative telling the story of Jesus from creation to new creation, where we’re invited to pick a side as we read – then why isn’t more of our preaching “narrative” flavoured? I’m not actually sure what that looks like – but I’m pretty sure it’s not a list of three propositions presented propositionally.

Anyway. The napkins. I haven’t listened to any of these (other than This American Life). But they are helpfully described in the post…

“Napkin #1″ is Bradley’s drawing for This American Life, a structure Ira Glass has talked about ad infinitum: This happened. Then this happened. Then this happened. (Those are the dashes.) And then a moment of reflection, thoughts on what the events mean (the exclamation point).”

“It starts with a straight line. That’s the opening scene where the reporter introduces listeners to a character often in action. Bradley gives the example of a story about ticks he produced for ATC. In the opening minute or so of the piece, we meet a biologist plucking ticks from shrubs in Rhode Island.

The dip down and up is what Bradley calls ‘the trough.’ “Throw whatever reporting you have into this middle section,” he says. In the “trough” of the tick story, Bradley included info on tick biology, lyme disease, and lyme disease research.

Then, the final line is a return to the original scene. Perhaps time has passed and the character is doing something new. But, it’s like book-ending a story — end close to where you started. Bradley’s tick story ended back out in the woods with the biologist.”

“The e” is what the Village Voice reporter drew for Bradley many years ago. The beginning of the line is the present or somewhere near the present. (Frankly, you can start wherever you want in terms of time, but the present or recent past is fairly common.) And, typically, there’s a character doing something — a sequence of events.

Then, at the point where the e loops up, the story leaves the present and, perhaps, goes back in time for history and or it widens for context.

When the loop comes back around, you pick up the narrative where you left off and develop the story further to the end. Somewhere in that second straight line the story may reach it’s climax then the denoument or resolution of the story.”

“The first line is the opening scene. Then, it’s followed by history, context…. a widening of the story. Then, a return to the opening scene only further along in time. Then, that’s followed by several characters each of whom have a connection to the story. That’s what the horizontal lines on the right represent.

When I spoke to Bradley about how a story might play out using this structure, he suggested considering a story about Lutheran ministers advocating for same-sex marriage in the church. In the first line, we meet a minister who is in favor same-sex marriage and he’s in church preaching. In the “V” we learn about the history of the issue in the church and the proposed changes. We return to the minister, perhaps at a meeting where he’s advocating his position and that’s where we meet several people linked to the issue and their perspectives.”

I also love this Kurt Vonnegut lecture about the shape of stories, which became a nifty infographic.

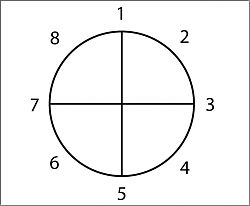

And then, of course, there is the classicly overthought Dan Harmon – creator of Community – who in order for his show to be so very meta, needs to have a firm grasp not only of how he wants to repackage stories and tropes, but needs to know how the stories he is dissecting work. He reckons there’s one universal story structure. His best tip from this series of posts about his story circle (part 1, part 2, part 3, part 4) is this one, about finding a relatable hook for your audience so they can take part in the story and be moved by it:

“sooner or later, we need to be someone, because if we are not inside a character, then we are not inside the story.”

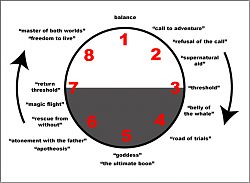

The Circle

Storytelling comes naturally to humans, but since we live in an unnatural world, we sometimes need a little help doing what we’d naturally do.

- A character is in a zone of comfort,

- But they want something.

- They enter an unfamiliar situation,

- Adapt to it,

- Get what they wanted,

- Pay a heavy price for it,

- Then return to their familiar situation,

- Having changed.

Simplified, his 8 steps look like:

- When you

- have a need,

- you go somewhere,

- search for it,

- find it,

- take it,

- then return

- and change things.

Harmon reckons almost all good stories follow this pattern – and, in fact, that it is innate.

“Get used to the idea that stories follow that pattern of descent and return, diving and emerging. Demystify it. See it everywhere. Realize that it’s hardwired into your nervous system, and trust that in a vacuum, raised by wolves, your stories would follow this pattern.”

Descent and Return

Why this ritual of descent and return? Why does a story have to contain certain elements, in a certain order, before the audience will even recognize it as a story? Because our society, each human mind within it and all of life itself has a rhythm, and when you play in that rhythm, it resonates.

Now you understand that all life, including the human mind and the communities we create, marches to the same, very specific beat. If your story also marches to this beat- whether your story is the great American novel or a fart joke- it will resonate. It will send your audience’s ego on a brief trip to the unconscious and back. Your audience has an instinctive taste for that, and they’re going to say “yum.”

The return bit is the most important…

“We need RETURN and we need CHANGE, because we are a community, and if our heroes just climbed beanstalks and never came down, we wouldn’t have survived our first ice age.”

Some story telling tips

Step 1 – Establish a (relatable) Protaganist:

“How do you put the audience into a character? Easy. Show one. You’d have to go out of your way to keep the audience from imprinting on them. It could be a raccoon, a homeless man or the President. Just fade in on them and we are them until we have a better choice… If there are choices, the audience picks someone to whom they relate. When in doubt, they follow their pity. Fade in on a raccoon being chased by a bear, we are the raccoon… The easiest thing to do is fade in on a character that always does what the audience would do.”

“He can be an assassin, he can be a raccoon, he can be a parasite living in the racoon’s liver, but have him do what the audience might do if they were in the same situation.”

Step 2 – Demonstrate a need: “We’re being presented with the idea that things aren’t perfect.”

“This is where a character might wonder out loud, or with facial expressions, why he can’t be cooler, or richer, or faster… This wish will be granted in ways that character couldn’t have expected.”

Step 3 – Crossing the threshold: “What’s your story about?”

“The key is, figure out what your “movie poster” is. What would you advertise to people if you wanted them to come listen to your story? A killer shark? Outer space? The Mafia? True love? Everything in grey on that circle, the bottom half, is a “special world” where that movie poster starts being delivered, and everything above this line is the “ordinary world.” Step 1, you are the sheriff of a small town. Step 2, strange bites on a murder victim’s body. Step 3… it’s a werewolf.”

Step 4 – The Road of Trials: preparing for the task at hand…

“Hack producers call it the “training phase.” I prefer to stick with Joseph Campbell’s title, “The Road of Trials,” because it’s less specific. I’ve seen too many movies where our time is wasted watching a hero literally “train” in a forest clearing because someone got the idea it was a necessary ingredient. The point of this part of the circle is, our protagonist has been thrown into the water and now it’s sink or swim.

Step 5 – The opposite of comfort: The climax at the bottom of the circle

“Imagine your protagonist began at the top and has tumbled all the way down here. This is where the universe’s natural tendency to pull your protagonist downward has done its job, and for X amount of time, we experience weightlessness. Anything goes down here. This is a time for major revelations, and total vulnerability. If you’re writing a plot-twisty thriller, twist here and twist hard.

Twist or no, this is also another threshold, in that everything past this point will take a different direction (namely UPWARD), but note that one is not dragged kicking and screaming through these curtains. One hovers here. One will make a choice, then ascend…

Step 6 – heading back up: symmetrical redemption.

“When you realize that something is important, really important, to the point where it’s more important than YOU, you gain full control over your destiny. In the first half of the circle, you were reacting to the forces of the universe, adapting, changing, seeking. Now you have BECOME the universe. You have become that which makes things happen. You have become a living God.”

Step 7: Bringing it back home: This is how the character ends up back where they started, having experienced the rollercoaster (and having been changed by it).

“For some characters, this is as easy as hugging the scarecrow goodbye and waking up. For others, this is where the extraction team finally shows up and pulls them out- what Campbell calls “Rescue from Without.” In an anecdote about having to change a flat tire in the rain, this could be the character getting back into his car.

For others, not so easy, which is why Campbell also talks about “The Magic Flight.””

Step 8: Showing the Change: This is where the protaganist is confronted with an opportunity to show that the ‘journey’ they have been on is worth it.

“In an action film, you’re guaranteed a showdown here. In a courtroom drama, here comes the disruptive, sky-punching cross examination that leaves the murderer in a tearful confession…the protagonist, on whatever scale, is now a world-altering ninja. They have been to the strange place, they have adapted to it, they have discovered true power and now they are back where they started, forever changed and forever capable of creating change. In a love story, they are able to love. In a Kung Fu story, they’re able to Kung all of the Fu. In a slasher film, they can now slash the slasher.

One really neat trick is to remind the audience that the reason the protagonist is capable of such behavior is because of what happened down below. When in doubt, look at the opposite side of the circle. Surprise, surprise, the opposite of (8) is (4), the road of trials, where the hero was getting his s*** together. Remember that zippo the bum gave him? It blocked the bullet! It’s hack, but it’s hack because it’s worked a thousand times. Grab it, deconstruct it, create your own version. You didn’t seem to have a problem with that formula when the stuttering guy (4) recited a perfect monologue (8) in Shakespeare in Love. It’s all the same. Remember that tribe of crazy, comic relief Indians that we befriended at (4) by kicking their biggest wrestler in the nuts? It is now, at (8), as we are nearly beaten by the bad guy, that those crazy sons of bitches ride over the hill and save us. Why is this not Deus Ex Machina? Because we earned it (4).”

What’s cool about this model is that it actually works for telling the story of Jesus. I think. And for telling our own stories. Like I said at the top – I have no idea what this does for preaching – I do believe we’re culturally hard wired for receiving stories, and I think that part of being God’s image bearers means being story tellers, if God is the master story teller who arranged the whole of creation and human history to tell his story, and then arranged for it to be masterfully told in a text that has lasted thousands of years, then something of that is essential to us. We all process our lives and new information through something like a master story too, events are incorporated into this narrative and interpreted through it (that’s why Biggest Loser contestants keep banging on about their journey).