There’s a chorus of voices — Christian voices — standing at the margins of the public square, and sometimes even getting into it — clamouring for one thing. The one thing we can agree on as Christians, and that we can agree on even with our Islamic, Jewish, or Buddhist neighbours… what do we want? Freedom of religion. When do we want it? Always.

But is this really something we need? Is it self-evidently a good thing, because it makes our lives better, because it unfetters the Gospel message, and allows us to love our neighbours well? Is religious freedom — freedom from persecution — an ultimate good, or is it just a good thing that we want? And how much of that ‘wanting’ is self-interest? How much of it is genuinely motivated by love for others — be they Christian brothers and sisters, or our Islamic neighbours?

Religious persecution sucks. And there’s certainly no place for Christians to be persecutors — though we have been, historically, and continue to be in certain pockets of the world — even persecuting each other. But should we be fighting for religious freedom, or is religious freedom (historically) a good bi-product of a thing that we actually fight for — the Lordship of Jesus.

A bigger question I think is how coherent it is to actually push for religious freedom in a culture where the dominant religious position — a sort of idolatrous secularism that enshrines a bunch of new gods — practices its religion by opposing and dismembering all the others. Sure, you can be religious, it says, so long as your religion conforms to our new easy-going, inoffensive, set of beliefs and so long as you don’t call into question the central tenets of individual freedom and identity construction — around like sexuality, gender, and the pursuit of happiness by whatever means possible. You can be religious so long as you chuck your core beliefs in and replace them with ours. Keep the trappings, the pomp, the ceremony, the rituals… but empty them of meaning and make them signify some other thing…

This is the religion of our culture. And if we’re to be consistent, affording its adherents and priestly caste the right to practice will ultimately destroy us, or them.

A recent post from elsewhere confronted people like me who might argue for the ‘romantic view of persecution’ — that persecution is actually good for us, posed these questions:

But I wonder if this view is in danger of so magnifying God’s sovereignty over history (and of persecution), that it ignores our responsibility to love our neighbour: wouldn’t such love include protecting our neighbour from harms such as persecution? … Now we Christians might feel ok about our basic freedoms gradually being reduced (at least in theory!): but what about our non-Christian neighbour: how might they fare in an environment where their basic freedoms of conscience, association, and speech, are rolled back?

But what if persecution is actually fundamental to our religious practice — our view of the world? What if the lens we’re to look through to assess the world and our experiences in it is the Cross, not some sort of worldly form of culture building or moral framework? What if the Cross is our moral framework? What if loving our non-Christian neighbour — especially potential victims of persecution — means standing with them and bearing the cost, not fighting to occupy a position of power and influence in worldly ways? What if the cross is actually where we start when defining neighbour-love? It was for John. It so defined his understanding of love, and of God’s love, that it became the paradigm for all acts of love in God’s name…

“ This is how we know what love is: Jesus Christ laid down his life for us. And we ought to lay down our lives for our brothers and sisters. If anyone has material possessions and sees a brother or sister in need but has no pity on them, how can the love of God be in that person? Dear children, let us not love with words or speech but with actions and in truth.” — 1 John 3:16-18

A quick reminder of the Gospel

The heart of the Gospel is the persecuted, crucified, king. Jesus. We’re called to take up our cross and follow him.

The power of God triumphs over worldly power and authority in the most unlikely way — through weakness, through persecution, through the sacrificial death of the king. Loving our neighbours — Christian, Australian, or global — will always look like us being like Jesus to them, and for them. This is how we know what love is. This, too, is how they know that we are Jesus’ disciples, that we have love for one another (John 13:35), and we’re not just sent to love our brothers and sisters the way Jesus does, but sent into the world to be like Jesus (John 20:21)… There’s a deeper richness in what John says in his first letter in these verses, but just note the links here between Jesus, the testimony of Jesus, the love of God, our knowledge of that love, and its implications…

“And we have seen and testify that the Father has sent his Son to be the Saviour of the world. If anyone acknowledges that Jesus is the Son of God, God lives in them and they in God. And so we know and rely on the love God has for us. God is love… In this world we are like Jesus…We love because he first loved us…” — 1 John 4:15-16, 17, 19

Every time John talks about love he has the character of God in view — “God is love” — and not in an abstract way, but the character and love of God we see on display at the cross. This is what love is. This is what loving our neighbour looks like. If you want to love your neighbour — and want them to know that your love is an echo of God’s love — then this love is always connected to the example of Jesus, not simply a figuring out what people think is good for them… what they think they need.

God is love. He’s also power. And the path to true freedom. And love, power, and the path to freedom are all on display at the Cross. Anything else is counterfeit, or some sort of shadow reality pointing to the ultimate. If you want to see freedom, power, and love as God does — look at the world through the lens of the cross. If you want to be powerful. If you want real freedom. It’s found in the Gospel, not some other picture.

The Gospel is the power of God that brings salvation (Romans 1:16), the world thinks the Cross, and the view it provides of God, is weakness and folly but it is the power and wisdom of God (1 Corinthians 1:23-25), and it is the pattern of life and witness we’re to adopt. Weakness. Being crushed, afflicted, destroyed. This is the picture of Christian life and love; of power and victory. Our victory procession looks like being the ‘scum of the earth, the garbage of the world’ (1 Corinthians 4:11-13). But we don’t really believe that any more. We’ve been conditioned by too many years of Christendom, or the comfortable idolatrous worship of morality that looked very Christian. The same man-made religion the Pharisees were condemned for… and now we fight for that idol in the face of our cultures new gods — sexual liberation and the freedom and safety to completely construct one’s identity without being offended.

It’s like we no longer believe this to be true:

“My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness.” Therefore I will boast all the more gladly about my weaknesses, so that Christ’s power may rest on me. That is why, for Christ’s sake, I delight in weaknesses, in insults, in hardships, in persecutions, in difficulties. For when I am weak, then I am strong.” — 1 Corinthians 12:9-10

“My power is made perfect in weakness”? Do we believe this?

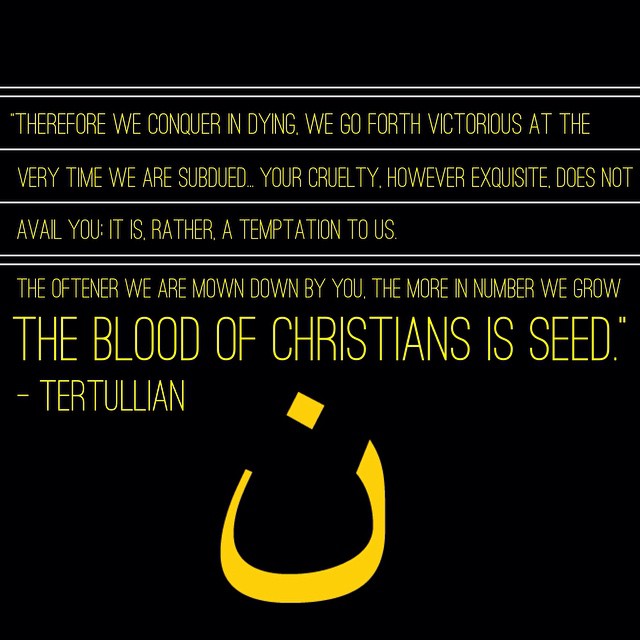

Tell me again how religious freedom is a fundamental need if we’re really going to love people? This is one of those things that Paul says, that John says, that Jesus says, and that the blood of Christian martyrs through time and space cry out, but we don’t believe it. We live as though real success looks like worldly victory and freedom in this world.

The Christian life is one of meakness and weakness. Sure, we offer temporary freedom from suffering and pain to people — but we do that by taking it on ourselves, or wearing the cost of fighting for it, and these are good things. But they’re wants. Not needs. We’re called to a life of persecution and suffering as we bear the cost of following a crucified king in the world that killed him, and the cost of loving those who are afflicted. Suffering with those who suffer, mourning with those who mourn. The beatitudes are not a funny parody that God made up. They’re no Babylon Bee article. They’re a real pattern; they’re the pattern that Jesus followed.

Salvation that comes through death and resurrection is the picture of freedom we’re to adopt. Real freedom. And this example is the picture of love we’re to adopt. Anything else offers false hope.

Until we start believing that God is the source of real power, real freedom, and real love, all we’re offering to our world are shadows and counterfeits. Until we start believing it then every time the world beats us down it’ll feel like a loss, not a victory. We’ll think we’re loving people if we’re offering up some analogy of the world’s view of power, or flourishing, or love… but let’s start with our first principles, about who God is, and who we are, and then with God’s view of the world…

A quick ancient history lesson

John and Paul wrote their gear about the Christian life in a secular-religious world. A world where people were free to have their own god or gods, so long as they first bowed the knee to the real ‘god’ — Caesar. The personification of the ultimate human empire. The image of human might and power. At least the Caesars didn’t pretend to be ‘secular’, they just declared themselves divine. As Rome conquered they absorbed the gods of other cultures into their pantheon, but all under the ‘secular’/state agenda. Until they got to Israel… The Jews kicked up such a stink about the idea of bowing to Caesar they were given a special dispensation so long as they prayed for Caesar, rather than too Caesar. Judaism was a ‘religio licita’ (a legal religion) so long as the Jews acknowledged Caesar as the real king, the real power. A dynamic on display in the trial and execution of Jesus.

John and Paul wrote all this stuff about weakness and power, about what we need to flourish, not just nice things we want, about what love for our neighbour really looks like amidst persecution. Not just soft persecution. The persecution that involved the execution of Jesus, and others, for claiming that Caesar was not really powerful; that the emperor had no clothes. This is what we’re called to testify to — not to win religious freedom, but to call out idolatry and its destruction, even in its secular form. At our cost. This is what neighbour love looks like. Not just laying down our possessions for those who are oppressed and marginalised, but being prepared to lay down our lives in defiance of other religious agendas.

The secular landscape — the public square — is not neutral. It is not a platform where natural law arguments win out. It’s a landscape controlled by beastly powers who want to keep overcoming the lamb. Because they’re ruled by fear. They’re also not really in control. Their destinies are assured by the one who is — so are ours.

John writes another book, or letter, into this political reality. Revelation. Oft-misunderstood. His apocalyptic vision presents the slain and resurrected lamb as the one who is really in control — even as he dies — and the beastly powers as what they are; losers with a godless, crossless, view of the world, of power, and of love. Real witness, real love, well, it looks like the same testimony he calls Jesus’ followers to in his Gospel, and his letters, being faithful witnesses who live like Jesus, at cost. The letter starts with seven churches who he calls to be faithful witnesses, he calls them not to get sucked into beastly, worldly, visions of power — the same temptation that lured Adam and Eve, and that Jesus rejected in the wilderness — he calls them to hold on to Jesus… and by chapter 11, only two are standing. Two lampstands. Two faithful witnesses, who ultimately share their king’s fate. First death. Then resurrection.

“Now when they have finished their testimony, the beast that comes up from the Abyss will attack them, and overpower and kill them. Their bodies will lie in the public square of the great city — which is figuratively called Sodom and Egypt—where also their Lord was crucified. For three and a half days some from every people, tribe, language and nation will gaze on their bodies and refuse them burial. The inhabitants of the earth will gloat over them and will celebrate by sending each other gifts, because these two prophets had tormented those who live on the earth.

But after the three and a half days the breath of life from God entered them, and they stood on their feet, and terror struck those who saw them. Then they heard a loud voice from heaven saying to them, “Come up here.” And they went up to heaven in a cloud, while their enemies looked on.” — Revelation 11:7-12

This is what faces us when we faithfully walk into the secular public square. It’s not secular and neutral; its hostile and idolatrous. Its beastly. The world is hostile, as John puts it in 1 John (and Jesus puts it in the Gospel), it’ll hate us because it hates Jesus, it’ll hate us because its full of people ‘secular’ types who, though they seem nice seem to want good things, and seem to be rational, are children of the Devil (1 John 3); people who’ve grabbed onto the temptation of worldly power, not to the Cross. This seems harsh, and perhaps it is, but John says there’s no middle ground. No neutral ground. The public square is hostile; the gatekeepers are against us. Without the lens of the cross — God’s way of seeing the world — we have the distorted lens handed to us in the first chapters of the Bible, by the serpent, so we get love, power, and ‘good’ wrong. The world doesn’t just reject Jesus, but his messengers.

A quick theological ‘positioning’ primer

We keep making the mistake of not seeing love the way God sees it, or ourselves the way the world sees us (and the way God calls us). This is not a ‘romantic’ notion; but the gritty reality. We are exiles. Strangers. Followers of a king the world rejected. Destined for the same scummy procession, rubbish in the world’s eyes but faithful and beloved by God.

Everybody worships. There is no real ‘secular’ we’re not just facing flesh and blood when we put forward a position but people and cultures who have been shaped by generations of rejection of God. In John’s apocalyptic, vivid, technicolour view of the world the beastly world, that views power the way the Caesars did, wants us dead. They don’t like the threat we pose to unfettered freedom to pursue your own identity. They don’t like a view of victory that involves an ugly cross. It’s a religion that can’t tolerate the freedom of other religions unless it dismembers them and leaves converts with a carcass to pick over or stitch on, Frankenstein-like, to their new religious identity.

This apocalyptic vision has to change the way we engage with the world. It has to change what we think love looks like, or needs, or freedom, look like. Love looks like Jesus. People need real freedom from seeing the world wrong. People need freedom from death and judgment. People need Jesus, not freedom to find their identity in some cobbled together god who doesn’t challenge the secular ‘reality’…

Not only do we seem not to believe weakness is real power, we seem to believe the world is our friend. A friend who can be cajoled and persuaded with good natural arguments or as we play the power game, lobbying for such goods as ‘religious freedom’ for everybody but the secular overlords. Rome had something like that… the religio licita. It’s not enough for us simply to want the secular world not to hurt us. To buy our freedom simply by seeking the welfare of the city or empire on its terms alone… We really do want a revolution, the revolution of hearts and minds as they find real freedom and power in the Gospel. In the blood of Jesus.

A quick look at implications

Religious freedom is a luxury. A luxury won, in part, through the blood, sweat, tears and sacrifices of Christians throughout the ages, I’m not suggesting we throw it away cheaply; I’m suggesting we rediscover the truths that underpin it. That we rediscover the radical sort of love for our neighbours that goes far beyond simply winning them the right to freedom of speech, but that comes from speaking freely to them, whatever false picture of god or power they have. I’m suggesting we stop throwing our lot in behind counterfeit gods like ‘freedom’ and start exercising the freedom that comes from knowing God really does love us, and he really is powerful, and real love and power is on display in the crushing victory of the cross — which looks like a crushing defeat. If we stick with this message rather than playing worldly games using worldly tools (like lobbying, using natural law arguments, or using force) then we avoid a bunch of issues, the sort of issues that arise when we’re inconsistent, the sort of issues that have seen Christians turn the sword against one another, or against others, the sort of issues that undermine our witness. We also make sure we’re being rejected for the right thing, for our core business — we’re not called to be hated because we’re different, Jesus says the world will hate us because of him.

We can’t actually call for ‘religious freedom’ and expect that it won’t lead to persecution because aggressive secularism is a religion, a beastly religion that co-opts power to destroy all other gods and assimilate people from all other faiths. I’m suggesting that we should work harder at believing the world isn’t going to love us when we proclaim Jesus, that the secular world is not neutral but opposed to us because it has a different view of power and freedom, and that weakness and apparent defeat is the norm — and what God works through our humble sacrifice offered in love for others.

This also gives us clarity when it comes to how we relate to governments. This is tricky, they’re a means of God’s grace to us, a means by which law and order happens, we’re told to pray for them, to live at peace with them, and to obey them. But the government these instructions specifically, originally, refer to is the government that executed Jesus. Rome. Paul’s approach to the representatives of this government in Acts presumably line up with what he tells us to do in Romans 13. And what does he do in Romans? He appeals to Caesar, he wants to get to Rome to make some sort of case for his approach to life (and we get a hint that the Gospel makes it into Caesar’s household in Philippians), and en route to Rome he preaches the Gospel to its representatives… hoping to convert them. Ultimately this is what happens to the empire… the Gospel is lived and preached and becomes too compelling to ignore (or genuinely converts the emperor, depending on your take on history). It’s ultimately this change, via the testimony of the Gospel — God’s power through weakness — and the love for those who are oppressed and marginalised by the beastly powers of the world that brings freedom of religion for people in the west. According to history, and the development of good things we like, like religious freedom and freedom from persecution, the lived and spoken demonstration of God’s love — the proclamation of the Gospel in word and deed — is the best way to oppose oppression and horrible, harmful, uses of power, the best way to love our neighbours, and the best way to secure religious freedom for those who disagree with us. Tolerance of alternative religious beliefs is not widely practiced outside the west (nor is it something Christians were/are all that good at). It’s how God works.

This puts our expectations more in line with the Gospel, history, our theology and the experience of persecuted Christians in the minority world. Christians who face physical persecution along with limitations in what they can say or do… It leaves us resting in our weakness, and relying on God’s ultimate victory being on display in death and resurrection.