Peter Lillback, president of Westminster Theological Seminary in Philadelphia is our guest today. He’s looking at apologetics from the vantage point of the scriptures… He called this “The Study of Scripture as a Scientific Pursuit” – it’s actually more accurately “an introduction to presupposition apologetics.”

These are my notes.

Knowledge is a great challenge and a philosophical question – “how do you know what you know” – that’s the beginning of the study of the Bible. When we’re defending the faith through the scriptures we’re claiming to know something both of the Bible and of God.

The study of religion is useful in apologetics.

What is religion – from the Latin roots – “the tying/binding together of things that are separate.”

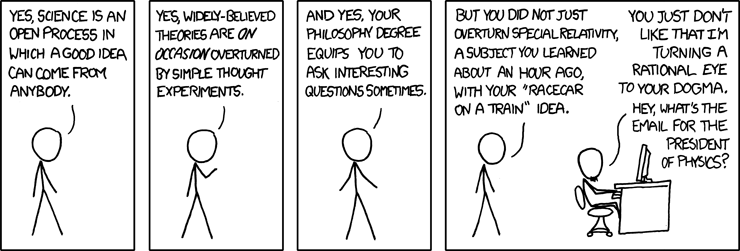

Scientism: I only know what I can know by the scientific empirical method. This is the form of religious skepticism that we know today. How do you put God into the test tube? You can’t. So taking this approach to religion doesn’t work.

The science of religion is different to the religion of science.

The science of religion – how do we know what we know? The study of the binding together of things (man and man, man and God) through religion…

This uses science in the broad sense of the word – it’s analogous to what a linguist, anthropologist or other pursuit of knowledge does (outside of the material sciences).

Think about religion in its broad sense – the way Paul Tillich considers it – “religion is that thing or person that is beyond everything else that we engage. It is that absolute transcendent reality or ultimate concern that defines us.”

Everybody has that ultimate concern that defines us. How do we really know what that ultimate concern is in our life? What is it?

Some of Lillback’s basic presuppositions:

- Everyone is religious – we all have an “ultimate” concern or a transcendent reality.

- Because all human beings are finite we all believe something – we’re limited, we’re not omni-anything, so some of our knowledge comes from belief or trust in something external. This is how we know, or think we know, what we know. The phrase “people of faith” applies universally – we all have a transcendent concern and a faith that comes out of that. These presuppositions come cf Abraham Kuyper. They necessarily therefore live their lives in faith flowing from that presupposition.

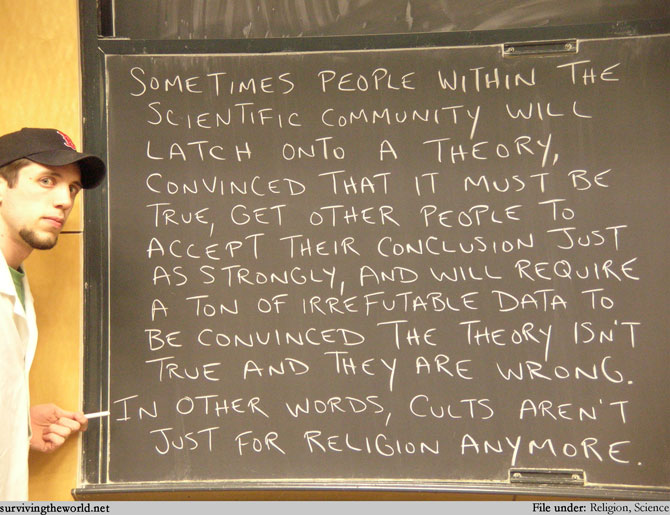

- Nobody is objective. We can not look at the world objectively. We all have these presuppositions that get in the way of seeing the “facts” – we all look at things and define them via our bias. Nobody is ultimately objective. Cornelius Van Til: “imagine a man of water living in a world of water who builds a ladder of water to climb out of the water so that he can see what is not water” – we can not escape what we have perceived and defined our world to be. If we bring materialistic assumptions to the world we can not help but find materialistic conclusions (that by nature exclude God).

These presuppositions must be engaged with the people we encounter. People try to engage the world in the following ways:

- Deduction: logical inference based upon the presuppositions in which we operate. The logic we use is like a refrigerator – if you put good meat into the freezer two days later it’ll still be good. If you put rotten meat in it won’t come out good. Logic is a capable tool, but not magical.

- Induction: gathering data together to draw conclusions.

- Intuition: instinctive knowledge based on our suppositions.

- Revelation – we can not know God by our own investigations, we will only know God if he reveals himself to us. The daring claim of the science of religion as a Christian is that it is impossible to know God without revelation.

As Christians we too are finite, and not objective (in fact our subjectivity is moderated by the Holy Spirit – not just our bias) – we put our faith in revelation.

Our framework is exactly the same as the non-Christians. Our presuppositions are the same. Our treatment of ourselves is consistent with our treatment of others.

We all have this transcendent point from which we operate. Everybody starts with preconditions born out of their presuppositions. Ours is “I believe that God has spoken through the Scriptures…” Following this presupposition we can stand on the word of the Lord. Taking this stance removes the ability for culture to pull us in ebbs and flows and beat us with erudite arguments.

Philosophers in the realm of epistemology suggest we know certain things to be true regardless of our experience (eg. if I took two apples from one side of the room and two from the other and put them in the bag then we’ll all agree that two and two makes four. We intuitively know this). We also have knowledge by experience (a posteriori). The Christian says we have that knowledge through our experience with the Bible. We also have internalised knowledge through the work of the Spirit (a priori). The Holy Spirit is part of our presupposition (ED Note: which provides interesting ramifications re: confirmation bias). Scripture is self-authenticating to those with the spirit (ED Note: which also has some interesting ramifications re: circular reasoning).

We are called as gospel preachers and teachers to ask people to experience for themselves rather than understand our descriptions, “taste and see that the Lord is good” – Millbank used Edward’s honey analogy.

The Science of Religion is the knowledge of our ultimate concerns. These ultimate concerns come with presuppositions. We all interpret our world through our presuppositions. Christians believe that the knowledge of God is only possible through revelation. We believe the Spirit gives us an a posteriori and a priori basis for trusting the revelation of God through the Scriptures. The Christian therefore is called to study the scriptures “scientifically” – this is a Christian epistemology of the study of scriptures… we talked about definition, presuppositions and method… which leads us to the scriptures.

Kuyper: There are two types of science in the world because there are two types of people. Those who are born from above by the Spirit and those who have not. These types of people will look at the world and the Bible very differently.

We look at the Bible as though it is God speaking to us – other “biblical scholars” study the words on the page very differently. Even when the Bible is open it’s a closed book to the second category of people.

Bible bits that support this view:

1 Corinthians 2: An extraordinary passage on the epistemology of religion from a Christian perspective. This is a rough paraphrase (Peter read from an NIV, I had my ESV in front of me)… starting from verse 10.

“But God has revealed it to us by his Spirit… only by those who have been touched by God can know these things… we have not received the Spirit of the world but the Spirit that is from God… The natural person does not accept the things that come from the Spirit of God because they are foolishness to him…”

Paul on Mars Hill (Acts 17): he declares his worldview and declares the need for repentance – Van Til said the greatest apologetic is to preach the Gospel.

1 Thessalonians 2:13

“We thank God continually because when you received the word of God, which you heard from us, you accepted it not as the word of men but as what it really is, the word of God.”

The word of God isn’t clever exegesis and stirring oratory but the way the Spirit works through the Bible.

Luther: I don’t defend the Bible, I preach the Bible. The Bible defends itself…

Apologetics from a Christian perspective is a declaration of the Bible’s truth from the Bible. And this is legitimate because everybody comes at the world with their own presuppositions.

Another analogy: an explorer visits a lost valley and discovers a lost people – a tribe where every person was blind. None of them had any idea what seeing was. And the explorer tried to explain to them what seeing was. Nobody believed him. They couldn’t fathom the existence of seeing. He spent time alongside them, becoming part of their community – one day they asked if he wanted to join the tribe – on the condition that he pluck out his eyes…

This is, apparently, an analogy for apologetics. Let the reader understand.