I feel like I’ve written about this before somewhere… but…

This week the West Australian Government banned, and then unbanned, the Australian Christian Lobby’s Martyn Iles’ roaming soapbox “The Truth of It” from two public venues it oversees; the Albany Entertainment Centre and Perth Concert Hall.

They should not have done this — and not just for commercial reasons (though that was the lever pulled, if I’ve understood correctly, by the venue partner to get the event back on — which, if true, just reveals that, as in almost all cases (see: woke capitalism), money is the actual idol at the heart of our culture, not sexual identity… sex sells, as it always has). They shouldn’t have done this because it is a power-hungry expression of something at odds with democracy and true secularism (plurality). They shouldn’t have done this because doing this reveals their own ‘state religion’ — the one they’ve replaced Christianity with.

Now. My take on the ACL is well-rehearsed in these parts — I’m not a fan.

So much so that Martyn has blocked me (or refused to host my views he finds troubling) on his Facebook page. That’s arguably a private space, and, sure, he’s quite welcome to block me if he doesn’t want to hear criticism of his brand of Christianity. That’s his right. I’ve also started limiting who can see and respond to my posts on Facebook too.

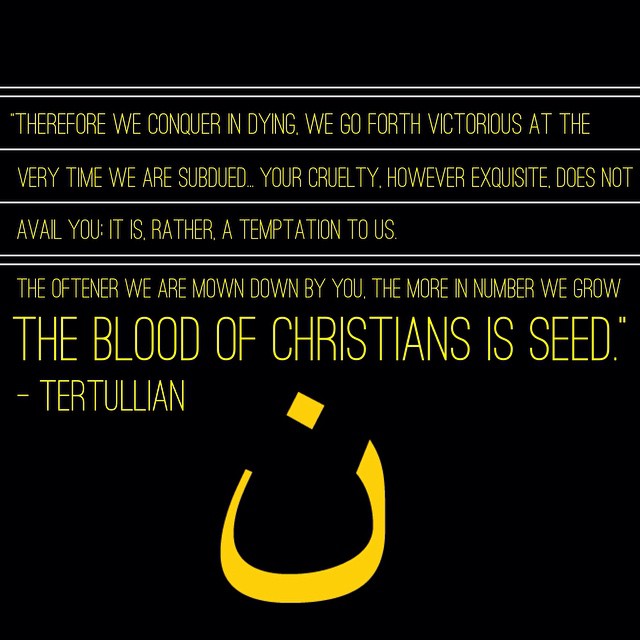

As much as I find the personality cult surrounding Martyn and his roadshow personally problematic, a government stepping in to cancel it is more personally problematic to me. This isn’t something to celebrate — especially if you are part of a minority group. This sort of government intervention around the use of public space — the demarcation of who acceptably belongs with a voice in ‘the public’ as recognised by the state — is dangerous.

In our first few years as a church plant, my church family met in a State-government owned theatre, many churches around the country meet in rented public school buildings. Public buildings that are available for hire to multiple faith groups and ideologies are an expression of pluralism and part of the bedrock of civility. We never had any pressure placed on us by our venue (we did, when we moved out due to renovations, get kicked out of a replacement venue because we aren’t an arts group and so were in breach of their leasing provisions). The hardening ‘secular frame’ in Australia which might mean these sorts of spaces become unavailable overnight, and my experience not having our own church property, means I’ve been telling anyone who’ll listen that church buildings are incredibly important (and we should probably stop selling them). They’re important for practical reasons — but as I’ll unpack below, I think they’re important for political, cultural, and theological reasons (and if we were good at architecture, on the whole, and didn’t just build multipurpose facilities that function as “non places“). Look. There’re going to be lots of generalisations in this post and they are just that… general observations.

My take on cancel culture is also well documented. I don’t like it (and it’s always religious). I don’t like this decision from the Labor Government in Western Australia. Governments, with strong majorities, banning voices who oppose “their views” isn’t just a slippery slope to totalitarianism, it’s an iron clad un-democratic use of power to disadvantage anybody who might challenge your grip on power.

I’m also, I think, on the treatment of public space as a religious contest for victory (toppling statues), rather than for a place where civility and a generous pluralism might play out — I’m not a fan.

I’m especially not a fan when Christians play, or enjoy, all these games ourselves. Toppling statues. Holding up Bibles outside churches after protestors have been tear-gassed. Only advocating for our own Christian freedoms (to the extent that, when we’re advocating for someone who denies the Trinity we’ll call them a Christian just to serve our broader project). Cancelling people whose views we don’t like… that stuff.

Now. Arguably the ACL both wants ‘religious freedom’ for Christians to participate in public spaces (and say whatever they want without consequences from their private employees), and to limit the ‘religious freedom’ of others participating in public spaces (like drag queen story times in public libraries, and gay couples calling their relationships marriage). They have been, I would argue, inconsistent on this principle of freedom in public spaces. Now, as an aside, I’m not saying I think drag queen story times are a public good, but I do think they are an expression of an essentially religious frame, and that anyone who says they’re ‘indoctrinating kids’ while running a Sunday School needs to be able to carefully explain what the difference is without imposing the Christian moral frame that doesn’t want kids grappling with adult content. They’re certainly an ideological use of public space that the ACL has opposed (and, surprise surprise, LGBTIQA+ political groups in Western Australia have supported an equal but opposite reaction against the ACL, celebrating the cancellation).

The secular governments in Australia at the same time have been increasingly treating public spaces as spaces to be free from religion, through an awkward definition of secularism that sees it as being ‘not religious’ rather than ‘not sectarian’, and through a weird secular-sacred divide that we religious people have also often enforced by pretending that religion does not affect every part of our life and being.

In ‘secular Australia,’ Religion is what happens in private places, like our hearts, our religious spaces like our Cathedrals, our Temples, or our Mosques. Or. You know. The prayer room in Parliament House. This decision from the West Australian Government is utterly consistent with other state governments, and the Federal Government, who want to restrict ‘religious freedoms’ to ‘religious spaces’ — because our governments, like most Christians in Australia, operate with this secular/sacred divide. So, we’ll protect (legally) a minister (like me) from conducting weddings outside our theology and “sacred” rites, or churches from employing non-religious people (or employing according to statements of belief and codes of conduct), and some people will even extend those protections to church run institutions (like schools), but we won’t protect a photographer or baker who, through religious convictions, won’t supply a service to a same sex couple (now, again, I think there are principles of hospitality and neighbour-love that mean Christians should feel free to offer those services without feeling like to do so means they suddenly adopt another person’s moral frame). The photographer and baker aren’t offered the protections afforded by ‘religious space’ because they are operating in public (even as private enterprises… it’s confusing). I do wonder what might happen if more churches had on-site bakeries…

The prevailing cultural narrative is that religion happens in private religious spaces, and that it doesn’t belong in public spaces. And we religious people have been part of creating that narrative in a bunch of ways. I’ll pick two. Firstly, “secularism” — including this divide — is a product of Christianity, and secondly, in the way we’ve used our own spaces as private rather than public.

Secularism is a product of the western world, which is for good and ill, a product of Christianity. They aren’t having these debates in Muslim countries. Secularism, depending on which ‘subtraction story’ you believe (those are stories that explain how we got from Christendom (where the vast majority of people and the architecture of society were built on shared religious beliefs) to where we are now (a pluralistic, fragmented nation with contested public space) is a product of explicitly religious movements before it becomes a product of the rejection of religion itself (that’s a bad modern ‘subtraction story’). Tensions between Protestants and Catholics about public space like who gets to build a Cathedral in a public square, or run a school, or influence the King and so win victory over the other are pretty similar to tensions around who gets to read stories in the local public library. It’s just our religious options have massively expanded (in what Charles Taylor calls “the Nova”). This expansion in religious options is also a product of The Reformation, which opened up the possibility of questioning traditional dogma.

Now. None of those historical changes are necessarily bad; as a Protestant, I’m glad we’re not all Catholic. I’m also glad that, for the most part, Protestants and Catholics have stopped killing each other (or even cancelling each other) because of religious differences and that now there’s even civility and dialogue.

What is bad, I think, is that with the disenchantment of space brought about by the Reformation, and the emergence of ‘the public square’ in the west, brought about (at least according to Jurgen Habermas) by the end of Feudalism (a divinely endorsed ‘order’ where space was given to people by divine birthright and there was no public or private, only land ruled by a sovereign monarch and ruled according to their will) and the birth of democracy (where you need space for ideas to be thrashed out and debated). There had, of course, been public squares in Greece, but its version of democracy was less universal than the democracies brought about in the west by the universalisation of the concept of the “image of God”.

Anyway. I digress.

See. The thing is.

Churches have always run their physical spaces as private spaces, as sacred spaces even — only opening the doors (in many cases) one day a week. Reinforcing, perhaps, the secular/sacred divide. Church space is here for you on the sacred day, but the rest of the time, all the other hours of your life, and on all other issues of communal life — wherever other discussions occur, the performing arts take place, or cultural artefacts are presented — that can all happen in secular space, and probably public space at that.

We haven’t been fantastic at bringing our own vision of beauty and culture and truth to the public square in part because we haven’t anticipated and reacted to change around us, in part because we’ve been busy reinforcing the secular-sacred divide in our practices, not only because we haven’t done ‘public Christianity’ well, but also because we just haven’t been using our own spaces well. There are, of course, groups committed to public Christianity — the ACL is one (and if Martyn’s the best we’ve got… then…), but also City Bible Forum, the Centre for Public Christianity, and a bunch of other organisations out there are doing this… but my point is that we haven’t seen the church (our local community, but also the visible church in Australia) as a public institution meeting in public sacred spaces, but private institutions (and often we ‘desecrate’ the places we meet by emphatically saying ‘they aren’t sacred’, rather than saying ‘these teach us how to view all space’).

We haven’t been great guests in the public spaces post-nova, in the secular age, where multiple religious views are brought to market for performance, recognition, and even debate. But, nor have we been great hosts.

We haven’t treated church buildings as public spaces — either as hosts who hold events for the public (outside of Sundays — and here I’m not talking about the way that churches use buildings to funnel people in to a Sunday service, that’s a ‘private use’) but events that use church buildings as a “public square” where other voices can be heard, or by inviting other people to use our facilities (where we might disagree with them). This isn’t universal, there are plenty of church buildings being used as community hubs out there… and plenty of church buildings that lose the Gospel and the call to be different from the world as they seek to play host, and so end up just as secular community spaces.

Churches are (typically) rightly careful about who gets to preach and teach in order to continue passing on the good news of the Gospel of Jesus (and maintain our distinctives), but we also have to figure out how to steward our spaces — whether our buildings will be public or private, or used in a way that reinforces the narrow view of the sacred, or in ways that break the secular-sacred divide.

But I reckon it’s worth asking the question — perhaps especially those in the West at the moment — would your church host a branch meeting of the Labor Party mid week (I’m not even asking about the pulpit)? And if the answer is no, and it’s about values, then we can’t jump straight to “but public space is different” — because we haven’t got a reputation for treating it differently (especially the ACL). Why should we ask the government to act as arbiters of a public square, when we don’t treat it as a truly public square ourselves (in excluding others), and when we aren’t using our own spaces as we’d want the government to use theirs? Why are we assuming that government is ‘secular’ and so ‘neutral’ (again buying in to the secular/sacred divide) rather than religious (and not Christian)?

We have a reputation for trying to exclude visions of human flourishing we disagree with from public life (again, think drag queen story time, or the same sex marriage debate). Public space isn’t different, public space has always been religious. Sometimes overtly, sometimes just because we have a theological frame, as Christians, that means we can recognise that every social political ideology is fundamentally religious, and every public act is liturgical. Because we are worshipping beings (and that’s the heart of being made to image God).

We also have plenty of religious spaces that we can start using to challenge the insidious secular/sacred divide that is so often at the heart of modern political problems; spaces that we can use (even architecturally) to proclaim that Jesus is Lord over every inch and every moment of life, but also spaces where we can make the truth public, and show that this means fearlessly inviting voices we disagree with to the table with us. Rather than silencing the voices of those who disagree.