The winsomeness discussion continues rolling on, with Stephen McAlpine declaring it the “Christian word of the year” for 2022. It’s a post worth reading and engaging with even if the debate over a virtue continues to confound me (I’m very much in the “winsomeness is a stance, not a strategy” camp).

“The big take away for 2022 is how Christians can engage in the public square in a way that is winsome. And if that is even possible. And of course the big question: Is winsome a strategy or a stance? We haven’t decided yet. We haven’t decided what winsome actually means. Does it mean speaking the truth in love? And when we’re told that certain truths that Christians hold can’t be loving in the first place, then we’re being told that we’re masking hate in love language. Where does winsome land in all of that?”

I want to offer a two-pronged rejoinder to Stephen’s post — and to the discussion. First up, you’d be forgiven if joining the current discussion around the word “winsome” for thinking it’s a totally new appellation for a strategy Christians have never had to embrace before the culture turned hostile.

Stephen asks:

“As the culture wars roll on, (and on and on) and Christians find themselves in the firing line on ethical matters, is winsome is our ticket out of this? That’s a great question to ask, if only we could decide what winsome actually looks like.”

It is a great question to ask — but it begs a couple of questions, first, are people advocating winsomeness seeing it as a “ticket out of this” firing line (or simply obedience to the Messiah who was met with the equivalent of a first century firing squad), and second, is winsomeness such a new concept we can’t actually understand what it means?

I’m sure some people are seeing winsomeness in utilitarian terms; thinking it’ll soften the blow if we’re nice — Stephen kinda assumes that’s why people do it when he unpacks the response to Tish Harrison Warren’s New York Times piece advocating pluralism that was hammered by an intolerant web-commentariat. But there’s a long history of arguing that winsomeness is a catchall heading for a Christlike virtuous life that seeks to make the Gospel beautiful; that it’s a way to describe a life shaped by the fruit of the Spirit, or cruciformity, in a crucifying world. And I’m not sure how helpful it is to simply assume the debate can be reframed away from the historical context that gave rise to the word.

I also think we have bigger fish to fry — and that’s the second prong of my rejoinder.

The first wave of winsomeness

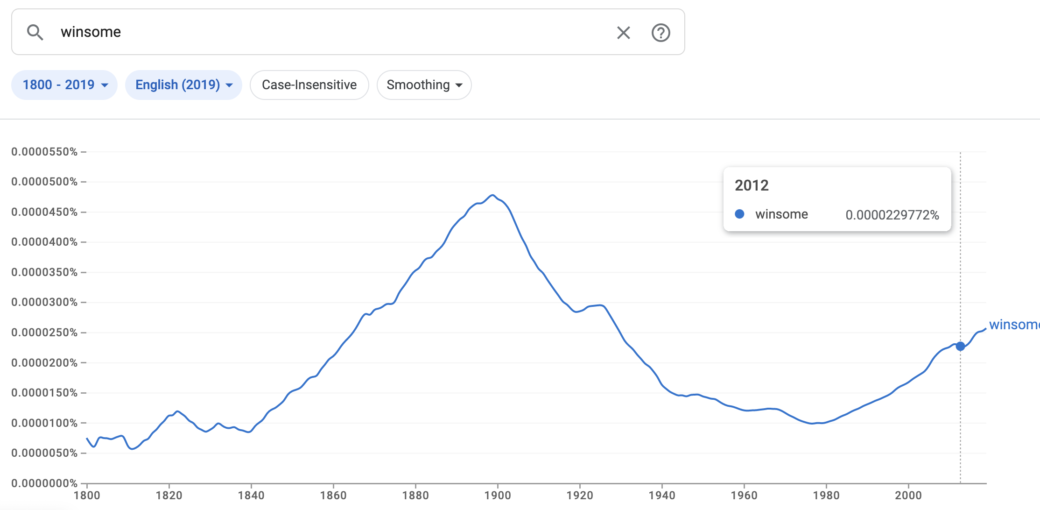

I was keen to dig in, a little bit, to the history of usage of the word “winsome” — so I used Google ngram to get a sense of when, exactly, it became a part of published discourse. We’re not even at peak winsome — we’re in the midst of a second wave.

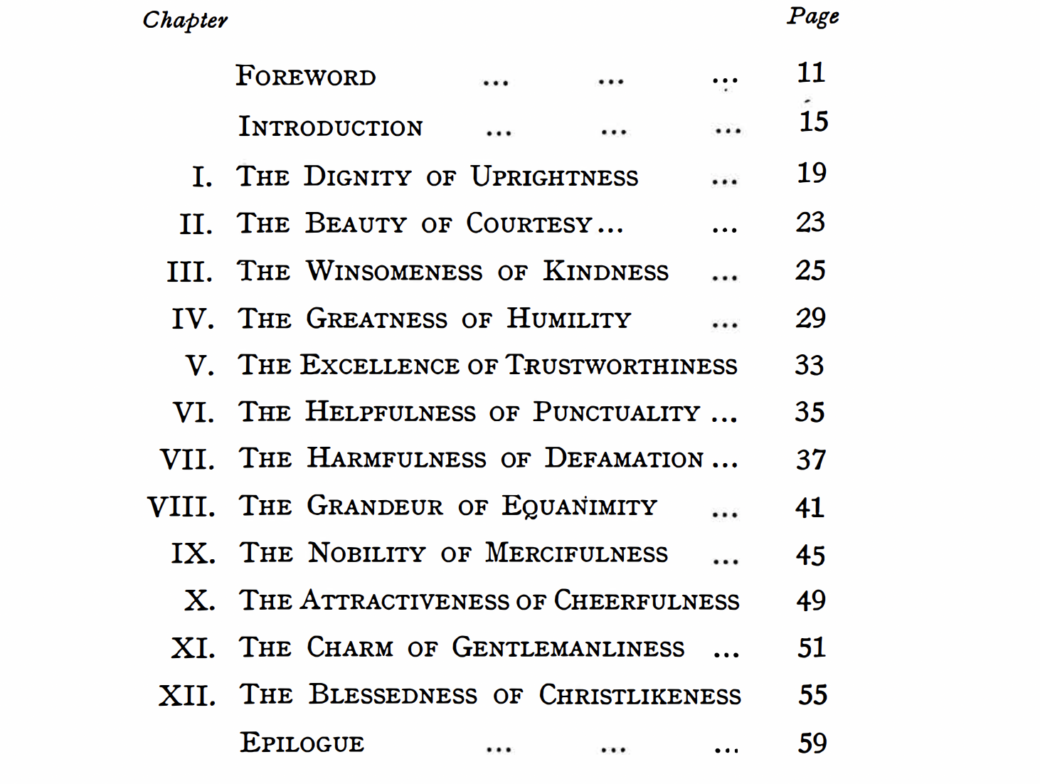

In this book Winsome Christianity by Henry Durbanville, published in 1952. Here’s the preface. Notice its emphasis on character.

Character is consolidated habit and is ever tending to permanence,” says Joseph Cook; and the saying is one of the greatest that has fallen from the lips of man. The traits of character that are spoken of in this little book are those which, if they be diligently cultivated and assiduously practised,. will ennoble the humblest life, filling it with radiant gladness and making it eminently useful. Thus refreshed and enriched, Christian men and women will, as they journey through this world to the ” Land that is fairer than day “, become true and effective witnesses to the grace of the Lord Jesus: like Abraham of old they will themselves be blessed and be a blessing to others.

And, here’s a screenshot of the table of contents.

If these character traits were the right thing to do (virtue) back in 1952, in the ‘golden days’ of modernist Christendom then they’re still the right thing to do today; to suggest these character traits were simply a strategy — or are a failed strategy — because the cultural context has changed is to assess character on the basis of utility rather than virtue (or our telos as bearers of the divine image). But I reckon this also suggests the “winsomeness” thing isn’t a fad, it’s a word that has been used to encompass these virtues (and the fruit of the Spirit) for at least 70 years.

Durbanville spends time in his Christlikeness chapter encouraging believers to develop a roselike fragrance of Christlikeness that is consistent in every sphere of life (it’s a stance, not a strategy, or perhaps more than a ‘stance’ that one adopts; it’s meant to be character so embedded in our lives that to present ourselves with integrity is to have these qualities on display in our lives). Christians — whether in public or private — should probably have integrity such that the character of Jesus is on display in us whether that’s a great stance or strategy, and regardless of the audience.

Our King has promised not only to visit us, but also to abide with us (John 14. 23). Is the fragrance of His presence diffused from us day by day ? If so, we shall be following in the footsteps of Paul who said : ” For to me to live is Christ “… There is one other thing which we would do well to note, namely, that a fragrance is the same everywhere. “He makes my life a constant pageant of triumph in Christ, diffusing the perfume of His knowledge everywhere by me” (2nd Corinthians 4, Moffatt). A rose smells as sweetly in the kitchen as in the drawing room; in the house of business as in the prayer meeting; on the playground as in the sanctuary.”

And earlier…

In March 1918, during World War 1, in the journal, The Congregationalist and Advance, in a section titled “In the Congregational Circle,” there’s a prayer recorded that says:

“O God, who in all times hast touched human lives with thoughts of thy kingdom of love, who even in the moments when that vision faded in defeat hast sustained those for whom it appeared, thou who wast in Jesus reconciling our world of error and sin with thy great glory and love suffer us not to forsake the hopes and visions of thy kingdom. Today when many would conclude that the kingdom which Jesus saw will never come, when followers of Jesus are entering into his own experience of defeat and of hope denied, grant us his steady confidence, his faith. Give us the grace to continue winsome and cheery, able still to bear light and love to all who have waited overlong. For Jesus’ sake. Amen.

How curious to pray that Christians might continue bearing witness in a world marked by suffering. That’s a modern fad. Of course.

We can go further back. To 1906. To a journal called The Religious Telescope.

On page 75, in an editorial, there’s a paragraph that reads:

“Winsome Christians are a godsend to a church. There are too many sour-faced, solemn Christians in the Church. Fault finding, evil speaking, criticism — these are the shadows that creep over a congregation, embittering the pastor’s heart. Be a winsome Christian in the church circle. Say nice things about people. Talk up the church work and workers. Tell the pastor that his sermon helped you. Give people credit for what they are trying to do. Winsomeness is contagious. It catches like a smile and passes from one to another. The church is too funereal in its services and arrangements. It needs more sunshine and song. Be winsome in church work.”

Winsome Christianity in the 1800s

Working further back… I’m a bit hesitant to share this one, because so many of the ‘anti-winsome’ brigade are against the ‘feminisation’ of Christianity, or ‘beta males’ or whatever, and I’ve got problems with the reduction of women’s ministry to ‘mothercraft,’ but in the magazine Lutheran Witness, in 1893, in a section titled “Christian Motherhood,” you can read this paragraph.

“You may fancy that the play-house is a safe school of morals and that the ball room is a safe school of refinement of manners; but if your daughters shall have learned quite too many things in those schools how will you like the apparel that you made for them? Remember that you are making the coat of character for your children. If you fashion it after a worldly pattern, then they may be poisoned with worldliness; but if you devoutly seek first for them the kingdom of Christ and his righteousness, and if you draw them by the powerful traction of a lovable, winsome Christian example, then you may hope to see them arrayed in the beauty of holiness.”

Again, winsomeness is being presented as a virtue — not a strategy (though, again, what you win people with, you win them to. Virtue is our strategy).

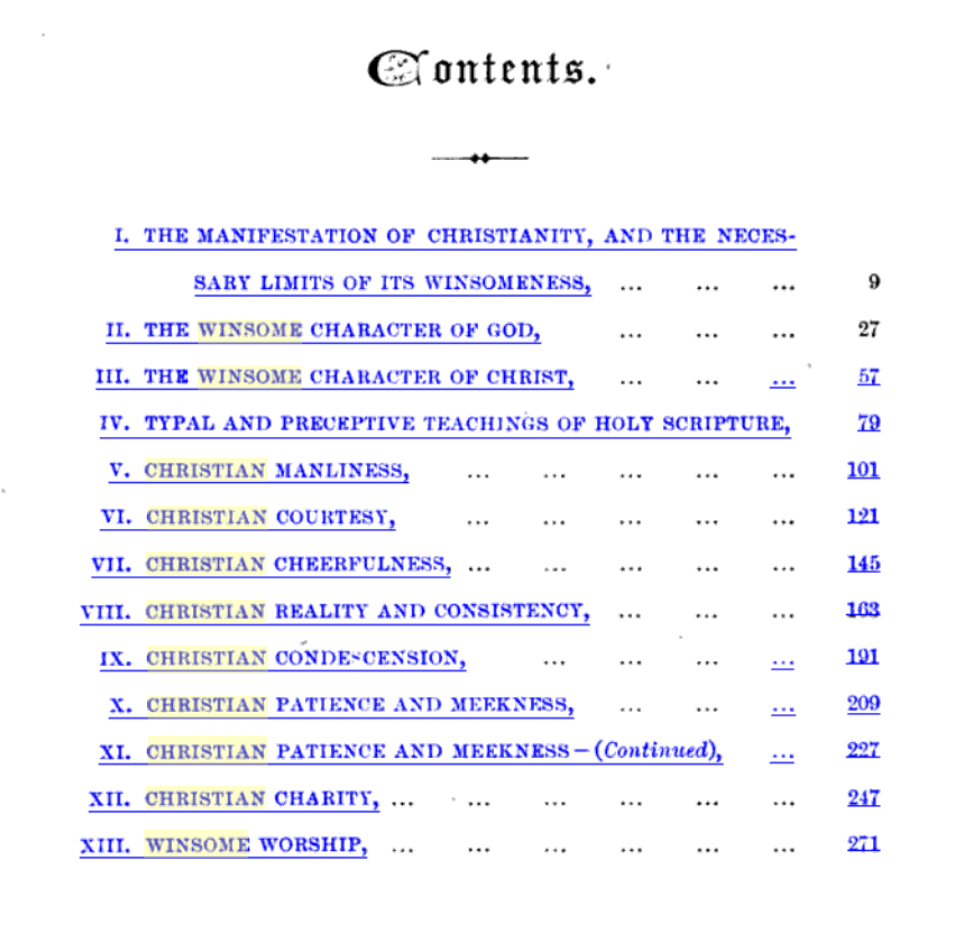

We can go further back, again, to a book, Winsome Christianity, published in 1882 by Richard Glover. It’s digitised on Google Books, and here’s its table of contents.

Again, a list of character traits, grounded in his observations about the character of God, in part as revealed in the person of Christ.

In his opening chapter Glover says:

“I do not mean by the title of this book to discuss so much the abstract beauty of Christianity, as the beauty of it when it is worthily embodied in the lives and character of Christians. In itself, of course, Christianity must be the most lovely and winsome thing the world has ever seen or ever will see. It is the highest and most perfect of all the works that God has created and made, and the lowest of which he pronounced very good. It is the flower or the fruit of all that has gone before.”

He goes on to say, of this beauty, that there are two chief ways it is made manifest in the world:

“One is by preaching, and the other is by the practical exhibition of it in the lives of its professors and disciples.”

And, subsequently:

“It will now be perceived then that what we mean by “Winsome Christianity” is the practical exhibition of Christianity before the world in an attractive and winning form. We do not intend to suggest by such a title “any other gospel than that we have received;” nor that the latter should be denuded of its essentials so as to accommodate it to man’s vaunted moral sense, as so many are attempting to do in our day.

Neither have we any wish to rob it of any of those elements which tend to make it more or less repugnant to sinful men, nor even to keep these in the background in the way of compromise to any human prejudice… when we adopt such a title, we have in our eye those ugly accretions that gather around it through human infirmity, which hide its true and essential beauty, and bring it into an unpopularity that it does not deserve.”

Glover’s aim was to appeal to Christians themselves:

“to point out to them certain defects of character and conduct which tend to make Christianity needlessly repulsive; to urge upon them the solemn duty of trying to correct these, or removing stumbling-blocks and causes of offence, and of putting on the more attractive ornaments of grace.”

The last bit of his intro relevant to conversations about winsomeness almost 150 years later, says “we must never forget that Christianity is in itself essentially repugnant to the unconverted or natural man. This is lamentably forgotten by the advocates of what is called “genial Christianity.” They seem to think that if Christianity be only fairly put before men they will fall in love with it at once. They think the whole fault is in the mode of presentation, and they take no account of the condition of the eye that beholds it. But this is a fatal mistake.”

Winsomeness used to be the word for people who recognised exactly what critics of winsomeness are now saying the ‘winsomeness brigade’ misses — there was already a word for this in historic debates — “genial” Christianity. I’m not suggesting modern bloggers should have read these potentially obscure 150 year old books — but, I don’t think we’re well served by thinking any posture is emerging in a vacuum in our present moment. There’s a long history of using winsomeness exactly the way I argued it should be used and understood in my previous post, and plenty of people using it the same way currently even if others — mostly those shooting at “genial Christianity” want to redefine it in order to police the term.

I’ve quoted these documents at length to make two points: firstly, the use of the word “winsome” has a pretty thick and rich history, we’re not left trying to define it with nothing but etymology and present usage (though someone had a crack at an etymological approach and a history of usage a decade ago). Second, people using the word “winsome” to describe a set of characteristics that “adorn the Gospel” are standing in a tradition that’s at least 150 years old, and not simply a reaction to the modern secular west.

There are plenty more examples from before the advent of the blogosphere and the Christian thought leader. I haven’t found many not making the case for winsomeness as a virtue — even if they link the virtue to how people might respond.

Now, I’m not denying that people are less inclined to respond to our winsome character in the public square in the modern west. I’m making the case that how others respond is not a reason to choose not to be winsome — again, because character matters when it comes to integrity, the Spirit produces the fruit of the Spirit in the lives of people who’re called to ‘bear the death of Jesus in our body so that the life of Jesus might be made known,” and, again, because what you win them with you win them to. I don’t want to win people to Christianity with manipulation, aggression, or a culture war (and neither did the Apostle Paul), but by sharing the Gospel and our lives shaped by the Gospel as well…

What if we’re actually the bad guys for a reason

I think there’s more to it than just ‘the culture is changing so winsomeness won’t cut it’ — and I think Stephen McAlpine’s book title (Being the Bad Guys) offers a prognosis (and a treatment plan), but not necessarily an accurate diagnosis of how we got where we are.

Firstly, if the case that the modern west is still essentially Christian in a whole bunch of ways (including our moral framework) then the standards applied to find us wanting — or to position us as “the bad guys” are essentially Christian. This’s a case well made by Tom Holland, Glen Scrivener, and Mark Sayers in a variety of works — I’m not going to reproduce it here.

We’re being found wanting based on standards we helped build — and perhaps it’s not simply because we disagree with the sexual ethics of our neighbour, but, perhaps because lots of us have settled on pluralism as a strategy a bit like closing the gate after the horse has bolted; after years of using whatever social capital and political power we had to not accommodate the other. Perhaps people aren’t prepared to offer us pluralism now — as the losers in a war, because we wanted the war, and weren’t prepared to offer pluralism as a good and loving option then.

The article Stephen quotes from the New York Times makes a commendable case for pluralism — after Obergefell in the States (and the Plebiscite here), but, to beat my own drum a little — some of us were making a case for a generous pluralism, on the basis of virtue rather than utility, before the law changed, and were shouted down (some good folks even went so far a to label me a heretic and a false teacher).

We’ve been found wanting here — and, without genuine repentance for the way we used power against the interests of those we disagreed with, how can we ask them not to use that power against us, when they have it? Especially if reciprocity (treating others as we would have them treat us) is not just a command of Jesus, but a virtue.

If our neighbours genuinely believe that to not fully affirm and embrace a person’s sexual identity is harmful, what we’ve modelled for them is to use every lever or power at our disposal to stop other people causing that harm despite their personal convictions or experience. And that’s outside Christian community — when I speak to friends whose experience situates them under the LGBTIQA+ umbrella who’re also Christians, who’re also committed to a Biblical sexual ethic as historically understood, I think it’s fair to say that every one of them carries hurt or trauma inflicted on them by the church. When Glover wrote of the “ugly accretions that gather around the Gospel” — this is surely one of them. Brothers and sisters in the family of Christ, who hold to a Biblical position on marriage and sex, can even find themselves excluded from their biological families who claim to be Christian over culture war shibboleths.

We aren’t always the good guys getting the bad treatment that we think we are. Sometimes we’re reaping the whirlwind, and the appropriate posture isn’t simply winsomeness, but a winsome modelling of true repentance seeking reconciliation.

What if we’ve given up on goodness for goodness sake.

The second part of my critique is basically that winsomeness is probably not a cardinal virtue; or, if it’s something we do in public, when presenting the Gospel, it needs to be matched commensurately with the virtue of goodness. We’ll only not be hypocrites so long as people’s experience of our goodness and love makes our words about the goodness and love of God resonate. And that’s just not happening. I think there are two ways that segments of the modern evangelical church — and perception is reality here, really, we’re all part of this church, so I’ll use we — we have abandoned the kind of behaviour that led to the church shaping the west. Let’s call it two ways to die.

The first way is the way of the culture war, let’s call this ACL Christianity, in the Australian context, or Caldron Pool bolshiness, where we attempt to hold on to the power we have accreted, at all costs (and the expense of others).

Our use of power (and influence) has produced great good, historically, but also great harm and confusion about the nature of the Kingdom of God. We’ve failed to do something Glover warned about back in 1882 — we’ve attempted in our approach to politics to clear “away that hedge that makes God’s true people a separated people… a people called out and separated from the world — that is, from those who will not have Christ to reign over them, but who live to self and who serve their own pleasures and their own sins.” That’s a basis of pluralism, actually, recognising that the Gospel — and the power of the Spirit — actually creates a new humanity and a new people who’re defined by separation from the patterns of this world. The pursuit of the reign of Jesus via the means of the state, not the means of grace — sometimes through a post-millenial eschatology — has caused substantial damage to our ability to be seen to be doing good as ambassadors for Christ, rather than as would-be Caesars.

The second way to die is, perhaps ironically, a function (at least in our corner of Australian evangelicalism) of the folks that brought us Two Ways to Live, and a reduction — whether intentional or otherwise, of the Gospel to personal salvation for a pie in the sky future through right belief, rather than being brought into a kingdom through believing loyalty and oriented to spirit-filled action as a redeemed creation. Let’s call the second way to die “Two Ways to Live Christianity”.

This reductionist shift included a turn to pragmatism (what tool’s going to save the most people), and a sort of utilitarian thinking that expands into how we construct church communities, and a turn against good works being “the work of the Lord.” This was, in part, a reaction against the Gospel-denying liberalism of some expressions of the social Gospel. The same thinkers who bring you Two Ways To Live Christianity also tend to insist that ‘the work of the Lord’ describes preaching, or word, ministry in the context of the local church. It’s interesting this then neglects the second way Glover suggested winsomeness happens back in 1882, through the “practical exhibition of the Gospel in the lives of believers.”

When we do the two step of reducing the Gospel to Two Ways to Live, which doesn’t have much of a doctrine of creation (beyond “God made the world”). There’s nothing in the first box about what he made it, or us, for, or a vocational sense of what we’re created to do as image bearers with creation, and then nothing in box six about what we’re re-created to do as people who’re now new creations by the Spirit, except to get to heaven. This, plus reducing the work of the Lord to preaching this Gospel, means we end up with an approach to the Christian life where winsomeness is only important if it helps us get converts, and where good works are somehow secondary to, rather than integrated with, the mission of (and proclamation of) the Gospel. By having a small target Gospel, and a small vision of the work of the Lord, we’ve minimised goodness as part of our witness (and as a quality that someone, or some communities, who publicly (re)present the Gospel should be known for… I made a longer version of this argument, with receipts, in Soul Tread magazine’s most recent edition.

The tl:dr; for this last section is that by reducing the Gospel to just words, and faith(fulness) to ‘belief in those words,’ and the speaking of those words, we’ve lost the impetus that led the historic church to live such good lives that they changed the world by making, humanly speaking, the Gospel more beautiful — by living winsome lives that meant even their crunchy words came with a backdrop of a community of people committed to loving and serving their most marginalised neighbours. Neither of these two ways to die give us the tools to make ‘winsomeness’ an effective strategy, and winsomeness, as historically defined, is an alternative way to live and present the Gospel to these two stances.

We’re told Christians should have a good reputation amongst outsiders, and now our reputation is for being the oppressor of those typically held to be the most marginalised neighbours in our community (though the tide is turning, and the power dynamics have shifted fast, such that we’re now the minority asking not to be oppressed). What are we to do?

I think the answer is the very New Testament idea of ‘living such good lives among the pagans…’ So this’s my argument here — prior to figuring out what it means to be winsome, and what place that has in public speaking about Christianity, we need to get our ethos in order — we need to rediscover what it means to be good; to live lives that guide the interpretation of our winsome words towards positive ends. We obviously can’t control that — to some the message (and way of life) of the Gospel carries the stench of death, to others it is the aroma of life.

As a Reformed Christian I’m pretty convinced, like Glover, that nobody comes to faith in Jesus without the Spirit making a person receptive to the Gospel anyway, and so in all this argy bargy about the changing world and our strategy/stance I’m much more interested in how our lives represent the character of God, and the so-called ‘audience of one,’ than about how we are received, and yet, there’re a few bits of the New Testament I reckon we could take more seriously when it comes to both the stance and strategy we adopt, and where we’re happy to be positioned in society.

There’s lots of people willing to say the church should be militant and aggressive, no matter who we destroy, in order to be faithful to Jesus — but at some point those actions aren’t an expression of faithfulness to Jesus, but faithfulness in the rhetorical equivalent of the sword, and our own strength wielding it. It also strikes me that when public Christianity is coming from Christian leaders, maybe more of us could consider this bit of Paul’s list of qualifications for elders, remembering that he’s opened chapter 2 with a reference to the ruling authorities, and that, in the context, he’s talking about the very same power-hungry idolatrous empire that crucified Jesus and persecuted Christians on and off until Constantine.

“He must also have a good reputation with outsiders, so that he will not fall into disgrace and into the devil’s trap.” — 1 Timothy 3:7

We’ve kinda tossed this one, haven’t we, except when it comes to “reputation management” when things come unstuck? But by then it’s too late, and it’s reactive, rather than pro-active. For Paul, this’s about how people see an elder prior to and during that appointment, not simply when they’re facing the court of public opinion (where, one wonders how you have a good reputation without something like the winsomeness described through history). We’re now quite happy to have elders and ministers who’re warriors positioned against the outside, with no regard to their reputation, and we’re seeing prominent pastor after prominent pastor fall into disgrace.

How exactly, I wonder, do we see such a reputation developing in a world where the institutional church is on the nose for our handling of abuse (of various kinds), where we’ve often played ‘reputation management’ games rather repenting, changing, and upholding the dignity of victims, and all those in our care? How do we rebuild a shattered relationship while also trampling on LGBTIQA+ people outside the church, let alone those in it, let alone those in it who’re committed to a traditional, Biblical, orthodox, sexual ethic?

Building that sort of reputation requires a commitment to reputation building, not just reputation management or spin, but actually the long hard work the church did for many years that’s left the modern western citizen “wanting the kingdom without the king” as Mark Sayers puts it.

I fear that in all the winsomeness discussion that focuses on how much we Christians’re being crunched in the public sphere — especially on questions around sexuality and particularly those in the LGBTIQA+ community, and their supporters and allies — kinda misses a big part of the point. And we’d be better off working out how to regain a good reputation amongst those neighbours, while living quiet lives respecting and praying for those in authority over us, in order to position ourselves for the winsomeness produced by God’s Spirit at work in us to shine through our words and actions.