The Machine church is geared — and iterated towards — perpetual growth; the ‘human scale’ church is an antidote that deliberately embraces limits to growth.

I plan to tell more of my own story as it relates to machine church in subsequent instalments — but to set the scene for part 2 I need to jump through the story from my first year ‘plugged in’ towards the last.

I want to be clear, too, and I will come back to this — that parts of life in this machine were exciting and some of its ambitions were virtuous. I want the kingdom of God to expand as people find life in Jesus and are united to him, and to his people, by God’s Spirit. I think the church is the means that the mission of the Gospel takes place and so I want the church to grow.

I would like it to grow in ways that are more like a tree or a forest, than like a computer network or machine or monopolising corporation or empire though; and for the growth to be natural and part of cultivating an ecology rather than overpowering and destructive to its surrounds (especially to other church communities). Part of the impulse of the machine, when it comes to growth, is that real growth only comes through the efforts and energy pulsing through the system that is ‘the machine,’ or networked to it, and not in more organic, sustainable and ‘small’ ways; the machine consumes and absorbs competition becomes totalising in part because of the competition for resources to fuel its growth.

I was part of the machine, fully plugged in and ‘complicit’ in perpetuating its growth (and the impact its growth had on humans, for good and for ill). I don’t write this to blame those engaged in the machine with me; or who still find themselves occupying similar positions in a community that has been through significant change since my decoupling from it. This is not an exercise in casting aspersions, but in self-reflecting. I wrote, or helped sharpen, many (though not all) of the words I quote below.

After I establish some of my own story, I’ll turn again to some material from Paul Kingsnorth’s Against the Machine, and an earlier essay on bigness, to draw some parallels between his diagnosis of what is consuming and essentially strip-mining the western world (and the natural world) and a machine-like approach to church growth.

My experience with the machine began first with my recruitment to the machine; I was still a student at theological college (so was Robyn, my wife — that will become important in subsequent posts). We were invited to ‘dream big’ — to join a church where we would be part of a compelling vision; and where, ultimately, I would bring my background in Public Relations to help establish a presence on social media because that was strategic. There were some hiccups in the recruitment process that, again, I will cover in the future, but I began my time ‘officially’ as part of the machine church at our annual staff retreat.

These retreats were vital vision casting moments for a staff team, that over my time at the church ebbed and flowed in size (along with various budget crises) with a high point of approximately 30 staff. At its peak this included as many as six ordained Presbyterian ministers, spread across three campuses, a number of ministry specialists (in kids, youth, and small group ministries), executive and finance managers, support personnel, and a media team.

In the first retreat I was one of many new appointments brought on to support the ‘big vision’ adopted by the elders the previous year. The elders would eventually become a “board” (combined with our managers), a relative novelty in Presbyterian governance, and most of the ordained ministers would be asked not to attend board meetings ‘voluntarily’ (I’ll also write a subsequent post about this; one thing people have observed about large churches is that they encourage ‘fauxnerability’ from those in leadership; I’m going to coin the term ‘fakountability’ — fake accountability — which is vital for machines to throw off limits to growth).

At this retreat we were rallied to the cause — and it was exhilarating. I had come to Bible College two years earlier from a regional centre (Townsville), from a pretty thriving church. My previous experience in Brisbane had been at a large suburban church that was efficiently and effectively engineered (by my father) around clear preaching of the word and a compelling, no-nonsense model of church that produced vitality and steady growth coupled with church planting and revitalisation partnerships with surrounding churches. There are machine-like tendencies in my DNA.

When we arrived in Brisbane as college students, my wife and I found ourselves ministering as students in a small suburban church within the geographic catchment of my former church that was struggling to grow to sustainability despite the faithful energy and effort poured in by the minister, his wife, and a faithful congregation supportive of the church’s mission. It had been a good two years experiencing ministry in a small suburban context, but I was ready to be excited. Before college my career was public relations, and this was in the heady early days of social media; before enshittification and the rampant growth of surveillance capitalism. I genuinely believed that social media could be harnessed for the Gospel — I even wrote articles on this site, and gave guest talks and eventually lectures at the Theological college I attended to that end. I no longer believe social media is an effective tool for evangelism; it is an effective tool for keeping people plugged in to a machine that is designed to deform and strip-mine their data by cultivating habits of attention that use dark patterns. And what you win people with, you win them to…

At this retreat we were, as I say, encouraged to ‘dream big’ — to imagine our church of 600ish as a church of 2,000 — and do everything ‘to that end’ — or, even, as though we were already there; there was a ‘build it and they will come’ mentality. By the next year’s team retreat we were planning to start a 4th Sunday service at the one location. The catch was, we encouraged members aka ‘ministry partners’ to attend twice on a Sunday; once to be served and once to serve — and we counted them twice. The data was always inflated; we were maybe never quite as big as we told ourselves (or others).

The ‘position paper’ adopted by the church leadership in 2011 told “Our Story” in the following paragraph:

“By God’s grace, we are a growing church and part of a growing mission. This growth is testimony to God‘s gracious provision across many years. From the decision to plant in the 1940s, to the decision to relocate in the 1990s, God has been at work growing his church. He has also been at work granting wisdom and strength to make the changes needed to keep promoting the unchanging gospel of Jesus and passing it on to the next generation. This is our gospel heritage. And by God‘s grace we are again growing and considering the changes involved in growing our gospel mission.”

That’s six uses of the words ‘growing’ and growth in one paragraph. That’s what we were about — the vision was to meet our “growth trajectory” which was taking us towards being a church of “2000 people” as a “medium-term rather than a long-term possibility.”

Conversations started, at this point, about what the actual limit to church size on our 15 hectare suburban block was with a smart redevelopment of a facility that was only around 12 years old…

One of our catch-cries, I think at every retreat I remember, was to refer to 1 Corinthians 9 and the idea that we were to become “all things to all people” — that we should use whatever means possible to win as many people as possible to Jesus. Our chosen ‘means’ at least for the first two team retreats, was to be a “large church,” dare I say, a “mega church” — given one definition of a “megachurch” is a church of 2,000 people or more.

By the second team retreat — and after a year where I was on the team and often in the room where it happens, even as a student — we had embraced a ‘2020 Vision’ to “Reach the city and reach the world;” complete with a pretty beautifully produced vision video (so well written and produced, in fact, that a large Anglican church in the hills district of Sydney copied it pretty much verbatim for their own 2020 vision — and when I discovered this and made a bit of a fuss online, this fuss turned out to be verboten because we mega churches like to stick together and pat each other’s backs).

Much like in the realm of technology, this pivot from mega- to multisite church involved a shift in thinking towards digital networks not just physical transport and logistics (I’ll unpack more on this below). In 2013, we added a media team — 3 video producers and a graphic designer — to ‘reach the world’ by producing content to broadcast online (including our church services). The conversation around my ongoing place in the team (I was still a student) was that I could be the media/online pastor generating articles and some scripts to pump out; PR for Jesus. Digital reach removed friction (including the friction of face to face human relationships) and maximised bang for buck.

By my third team retreat we had shifted our goalposts (and our focus) to being a multisite church gearing up our ‘infrastructure’ so we could be a church with 200 campuses, or churches signing up for our resources — because, why limit ourselves? That’s not a typo. We were genuinely invited to dream big; to choose the right suite of technologies and techniques to grow big or go home.

Again. Intoxicating — even if back then it already seemed a bit hyperbolic.

The whole point was removing limits for the sake of the Gospel; to create efficiencies and to avoid the pitfalls of other networks (like denominations) ,which got in the way. I was now going to be the campus pastor of a brand new and shiny city campus — we would spend the money from the sale of an inherited church property in the same ‘patch’ of Brisbane to fund the start up. We launched our first service at the Queensland Theatre Company in 2014.

The idea was you should engineer things as you built them in order for them to scale up rapidly and be easily replicable; you would make better decisions in the beginning; you staff for growth — to be ready to meet the next stage or two stages ahead so that you are always able to expand.

Later down the track, after some multisite misfiring, we spent a day with a multisite consultant from the U.S. He described a variety of multisite models from a denomination, to a network, to a franchise (there were a few other stops along the spectrum). The franchise, he said, was the most efficient. In the U.S, according to this guy, there were churches who had warehouses with trucks fully loaded with the equipment needed to set up a campus, just ready to roll out and set up. Turn on the lights. Much like a fast food franchise leverages the standardisation of the ‘non-place’ so that every location feels the same. This was, for some in our leadership, the dream. It wasn’t mine — and that’s one of the points where the wheels started to fall off. I did not believe in standardisation — the urban context our church operated in, with a community of people gathered by affinity from across greater Brisbane was not the same as the suburban context where our mothership had a large building, and an established ongoing presence in the area that stretched back decades (and a very very big carpark).

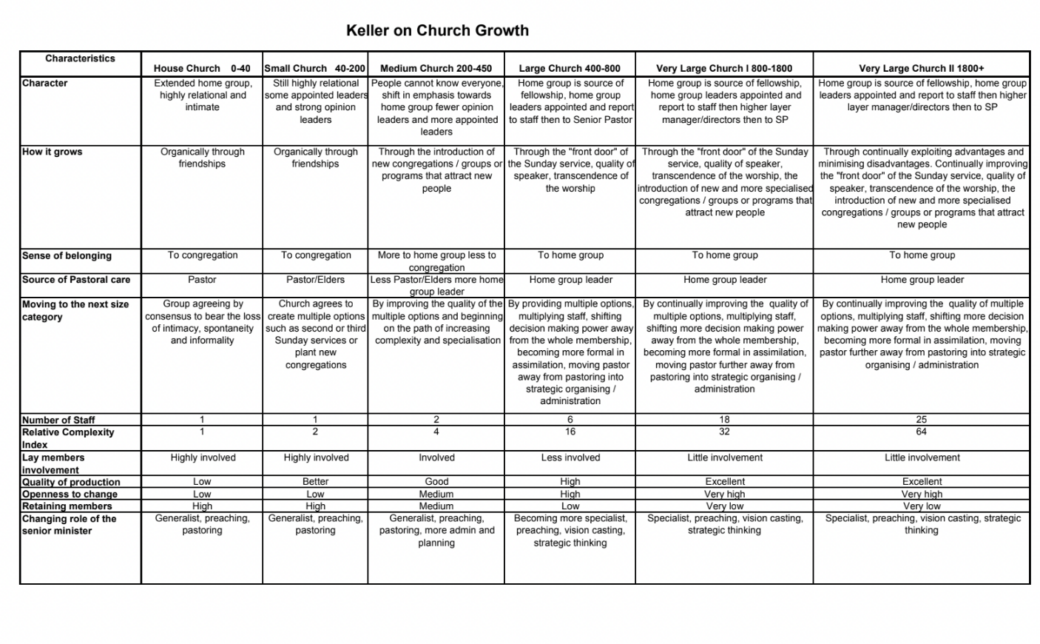

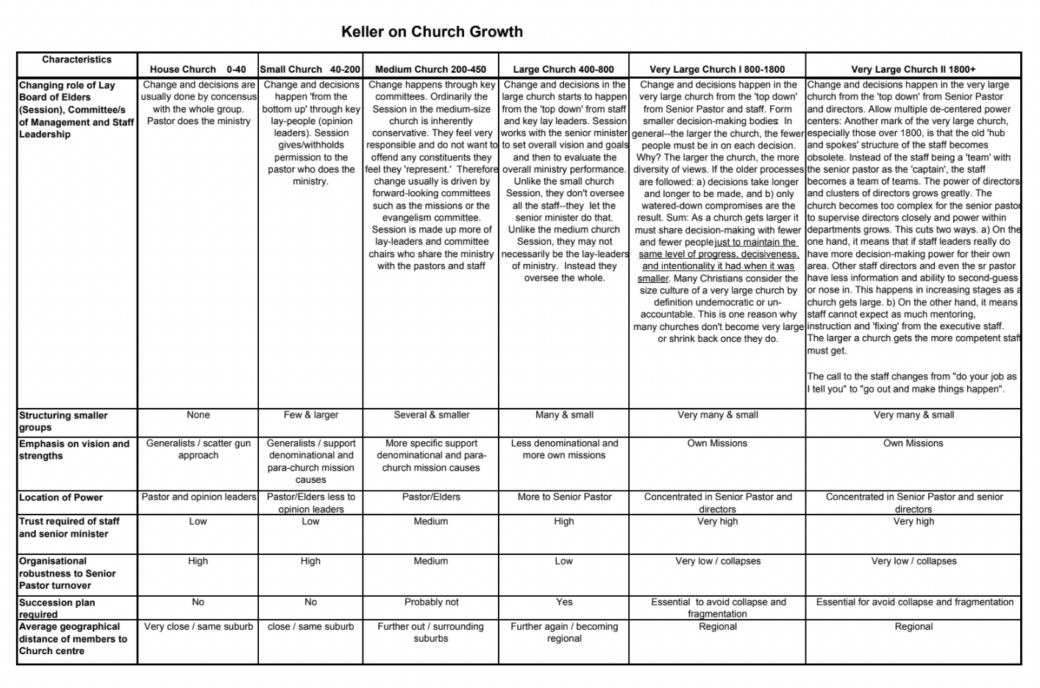

Our manual for thinking about growth and the structures to accommodate it — flagged right from the first vision document approved by the leadership in 2011 — was Tim Keller’s paper ‘Leadership and Church Size Dynamics: How Strategy Changes with Growth’ published in 2006. What Keller described; we prescribed and attempted to systematise. It’s an interesting paper — and particularly interesting to read after Keller’s retirement from Redeemer; where the megachurch that had gatherered around his leadership became a decentralised into a ‘family network’ of autonomous churches (a change announced in 2014).

“One decision we have made that encourages me is that Redeemer will become a family of congregations, not one centralised mega-church.”

In the church size paper, Keller wrote:

“Every church has a culture that goes with its size and which must be accepted. Most people tend to prefer a certain size culture, and unfortunately, many give their favourite size culture a moral status and treat other size categories as spiritually and morally inferior. They may insist that the only biblical way to do church is to practice a certain size culture despite the fact that the congregation they attend is much too big or too small to fit that culture.”

Keller ultimately lays out various aspects of ministry across different sizes of church, but in his discussion before the table he makes the following point:

“…the larger the church, the more a distinctive vision becomes important to its members. The reason for being in a smaller church is relationships. The reason for putting up with all the changes and difficulties of a larger church is to get mission done. People join a larger church because of the vision—so the particular mission needs to be clear. The larger the church, the more it develops its own mission outreach rather than supporting already existing programs. Smaller churches tend to support denominational mission causes and contribute to existing parachurch ministries. Leaders and members of larger churches feel more personally accountable to God for the kingdom mandate and seek to either start their own mission ministries or to form partnerships in which there is more direct accountability of the mission agency to the church. Consequently, the larger the church, the more its lay leaders need to be screened for agreement on vision and philosophy of ministry, not simply for doctrinal and moral standards.”

I would say, rather, that the larger the church the more standardised the vision and execution become across other churches of the same size — vision becomes more motherhood and generic; able to be photocopied — or with vision videos that are able to be plagiarised — because the vision simply becomes to grow; to keep pushing beyond limits — and expanding — through technique, as new members are folded in like cogs in the machine — as the mission of the Gospel becomes more and more aligned with the ‘mission of this church’ — and faithful participation in that mission as disciples becomes faithful service to a philosophy of ministry and vision.

We tabulated the Church Size dynamics paper and used this table as a kind of guideline for where our campuses were at in the matrix. We also struggled to map multisite realities of centralised resources and production values with ‘house church’ vibes.

The machine, by its nature, standardises. The machine church has a standard model for blasting beyond limits that it borrows from the corporate world — the world of the machine — for reasons that are historical and ecological; a product of the technologies that birthed the possibilities for growth via the eradication of limits.

Keller’s paper, and this quote from Larry Osborne’s Sticky Teams were referred to in most documents about our trajectory from here on in.

“Never forget, growth changes everything. A storefront church, a midsized church, a large church, and a megachurch aren‘t simply bigger versions of the same thing. They are completely different animals. They have little in common, especially relationally, organisationally and structurally. It‘s not that one is better than the other. It‘s just that they‘re different. Leadership teams that fail to recognise or adapt to these differences inevitably experience unnecessary conflict or shrink back to a congregational size that best fits the structures and patterns they cling to.”

The impact of this Church Size Dynamics paper being applied to our vision to be a ‘mega church’ was that we were attempting to operate as a ‘very large church’ while arguably a network comprising of a house church, a small church and a medium church. And we were trying to fund the infrastructure of a very large church from this congregation; and then, increasingly, from external sources — whether a user pays subscription model to our resources, or via corporate donors from the big end of town who I speculate may have moved on to fund other similar church planting and resourcing networks and initiatives with similar reach-shaped visions.

I think it’s possible that there actually is a size and a structure where a community is ‘a church,’ and a size where a community must embrace the machine and distorts to being ‘no longer a church’; becoming subject to different technologies and techniques in order to continue to grow by overcoming limits. I don’t think church size is spiritually neutral because it seems to me that to become certain sizes one must embrace methodologies no longer consistent with the nature of a human community, choosing instead to become ‘mechanical’ in nature. Where any person draws the line will be arbitrary — some say more than one service in one location is actually ‘more than one church,’ others might say ‘multisite church’ is a contradiction, for mine, provocatively, my suggestion is that this size could be described as a “human scale church,” with all the human relationships and accountability structures and community and collaboration that involves. For various reasons, my inclination is to see this aligning with the ‘small church,’ which caps out at 200 people. Maybe I’m clinging to a personal preference or moralising my ‘favourite’ size. You can decide.

The thing about a vision so big is, well, its bigness — it removes any limits around what this particular local church in its particular locality might justify as its local mission and replaces ‘local’ with ‘growing’ and ‘reaching.’

To be fair, locality is an interesting concept when it comes to the modern city and the modern church and the myriad choices available to any Christian living in a city to find a community — does one look for church community where one lives, works, or plays? Whatever church we attend is a choice. This is actually relatively historically novel; and aided by technological and social change.

We live in a world described by Charles Taylor as being shaped by the ‘age of mobilisation’ — where we are no longer pinned down in one geographic location for life (thanks to both social mobility enabled by political and social revolution, and technologies like the automobile and aeroplane), or in one vocation (thanks to technological, industrial, and digital revolutions that broaden the career options available and where work happens) — and the ‘age of authenticity’ where we each cultivate our presence in the world chasing our own ‘expression of self’ based especially on consumer choice and performance (also aided by technologies).

Taylor wrote A Secular Age and Sources of the Self after the internet had occurred, but in the very early days of social media and when Artificial Intelligence was the province of science fiction storytelling. The implications for church membership of mobilisation and authenticity (and post-protestant revolution which created brand ‘choice’ or what Taylor called ‘the nova’) is that church is a choice that individuals make and we make them for individual reasons often disconnected from geography and more aligned with affinity to various other things — people, theological vision, tradition, aesthetic — this consumer choice is fuelled by technology; and the mega church is a creation of technology — and, I would say, of the ‘machine’ as defined by Paul Kingsnorth and others.

This isn’t to say that house churches or small churches can’t be ‘machine’-shaped; of course they can; this is our prevailing culture. I’m seeking, rather, to make the case that big-to-mega churches are necessarily machine-driven, mechanistic or mechanical — relying on technology and technique and shaped by the prevailing conditions of the world around us with a desire to eradicate limits and extract resources in the name of perpetual growth.

At this point, I want to throw in a refresh of Paul Kingsnorth’s ‘machine’ definition, and foreshadow here that I’ll land trying to articulate ‘human scale’ church as an antithesis to machine church (whether that’s small, medium, large or mega-).

In my last post I highlighted a quote from Against The Machine where Kingsnorth wrote “The Machine manifests today as an intersection of money power, state power and increasingly coercive and manipulative technologies, which constitute an ongoing war against roots and against limits. Its momentum is always forward, and it will not stop until it has conquered and transformed the world.”

Grow. Growth. Growing. Growth. Growing. Growing. Reach the city, reach the world.

I also quoted this bit: “The ethos of the Machine is expansion, the busting of limits and the consumption of whatever can be sold to us to meet the ‘needs’ of the individual self which the Machine constructed for us in the first place.”

Our machine church with its emphasis on ’52 Excellent Sundays’ where one could receive ‘transcendent worship experiences’ (no sub-par musicians on stage thanks), and TED style sermons with original graphics and companion videos produced on cutting edge video technology was competing with every other church in our geographic pool to attract ‘ministry partners’ who would give their time and become ‘giving units’ “opening their hearts” to Jesus and then “opening their wallets” because “soft hearts give hard.”

Kingsnorth sees the ‘west’ as inextricably linked to ‘the machine’ such that to engage in ‘western’ practices uncritically is to participate in the machine. Its values are growth and profits and expending profits to secure more growth.

“‘The West’ has become an idol; some kind of static image of a past that maybe once was but is now inhabited by a new force: the Machine. ‘The West’ today thinks in numbers and words, but can’t write poetry to save its life. ‘The West’ is the kingdom of Mammon. ‘The West’ eats the world, and eats itself, that it may continue to ‘grow’. ‘The West’ knows the price of everything and the value of nothing. ‘The West’ is exhausted and empty.”

We were an extraction machine — and this included extracting the time, money and talents of the staff. At one point in a giving crisis, staff giving was being monitored, and senior staff (including me) — most of us renting as close as possible to church at great cost (percentage of our income), had a face to face meeting with the executive team (all a generation older, owning their own homes) and told to tithe our salaries, and to stop visibly spending money on things like fast food (because optics mattered). And, through technology and technique we convinced others to invest in the machine; to invest in the machine. Page 2 of one of our vision documents, titled “Investing in the Next Generation” used the word “invest” 12 times on a single page.

A few pages later the document said:

“We need to invest in people, in the precious people God is bringing to us. We need to invest in the next generation of believers. We need to invest in the people God is raising up from among us to send out as the next generation of labourers in his harvest. In all of this, one more pressing need is very clear. High level management is essential to maximize all our other ministry investments.”

We need to invest in getting our techniques right — and we are the vehicle for this mission. This rhetoric would amp up in subsequent years. People giving ‘hard’ to perpetuate the machine; invited to do so because of the urgent imperative of the Gospel — but the ends of the Gospel were totally identified with expanding our reach and growing beyond limits; even if people were chewed up in the process. Soft hearts gave hard.

I would note at this point, that a feature of machine church — with its acknowledgment that people will leave as you grow — crassly expressed by Mark Driscoll as ‘bodies under the bus’ — is burnout and exhaustion. Once resources are extracted from ‘ministry partners’ because in the parlance of pokie machines they have ‘played to extinction’ they are replaced by newer models and discarded. It is instructive that in a quick survey of vision documents from machine church over the four year period described above, around 80% of the members and staff named in the document are no longer employed by or attending the church.

The problem with the machine when it meets church is that it’s more like Moloch than the one who says “come to me those who are weary and burdened and I will give you rest.” Moloch as Kingsnorth describes it (following the beat poet Ginsberg’s Howl).

“What Moloch wants—Moloch whose soul is electricity and banks—is sacrifice. We must sacrifice ourselves and our children to the robot apartments and stunned governments.”

Kingsnorth writes, at some length, about the relationship between the machine and spirituality (and worship). One issue he identifies is that when we embrace the mediums and methods of the machine — the machine forms us (the medium is the message, thanks McLuhan), and it forms us in its likeness and machinations — not as humans, but so that we are extracted and exhausted.

“In a world in which this Machine consciousness is propagated to us daily through digital technology each time we gaze at a screen, the irrational, illogical world of beauty, wild nature and spiritual truth becomes literally impossible for us to experience, for it cannot be quantified—and therefore doesn’t exist.”

He describes our modern experience in terms similar to Taylor’s, so we westerners, entranced by the machine are “Spiritual but not religious, individualistic on the surface yet conformed beneath to the needs of the Machine, spiritually hungry but devoid of guidance or direction, committed to total self-expression yet unsure who or what we even are, suspicious of any limits to all these enslaving ‘freedoms’: this is our world. One that celebrates the free play of individual desire, that spiritualises the individualistic war on limits, and centres and celebrates the use of technology to win that war—in our bodies as well as the world.’”

We were a church that sought to harness technology and technique — the machine — in our models — mega, multisite, and ‘digital producer’ — breaking limits to win a war; but as soon as we fought this way we were losing.

Though he has converted to Christianity in part as a result of observing the consuming power of the machine, and how the cross of Jesus is its antidote, Kingsnorth notices the way Christianity has been co-opted.

“I learned from that experience that my belief in the profanity of technology is not widely shared. While there have been astute religious critics of the Machine—Wendell Berry, Ivan Illich, Jacques Ellul and Philip Sherrard have all made appearances in this book—it appears that many spiritual leaders and thinkers are as swept up in the Machine’s propaganda system as anyone else. They have bought into what we might call the Myth of Neutral Technology, a subset of the Myth of Progress… On and on it goes: the gushing, uncritical embrace of the Machine, even in the heart of the temple. The blind worship of idols, and the failure to see what stands behind them. Someone once reminded us that a man cannot serve two masters, but then, what did he know?”

In my next post I’ll explore the way the mega church — and the idea of perpetual church growth — the blasting of limits — is a product, directly, not just philosophically, of the machine (first the ‘automobile’) — and tease out some implications.

But here I want to nod towards the beginnings of Kingsnorth’s proposed solution; around the idea of embracing limits — and dip back into an older essay of his to introduce the idea of ‘human scale’ church.

Perhaps the first step of resisting the machine — following Kingsnorth — is to refuse to see (or describe) things that are not machines as mechanical; to cultivate a different imagination — and especially to see organisms and communities as organic rather than technologies to systematise or master; to resist dehumanising language (‘giving units’) and, like the good shepherd, know each sheep by name. Kingsnorth says:

“Perhaps central to this is an effort to see the world as an organism rather than a mechanism, and then to express it that way, through art, through creativity, through writing, through our conversations. The last part is the hardest, very often, but maybe the most important too. If we refuse to see the world or its inhabitants as machines, if we are suspicious of rationalisations and dogmatic insistence and easy answers and false divisions, even for a moment, then we are making a start.”

One of the moments in the life of our church where the machine took over was a time where I had not been living within my own limits — or boundaries — in pastoral care; all things to all people became a mantra not just for evangelistic technique but for constant availability to offer assistance of any manner; fuelled by being constantly contactable. This was bad and my family suffered, I suffered, and the people I cared for suffered — but the solution, proferred by the machine, was to essentially remove me from the same sort of ‘face to face’ contact with people; to move me across Keller’s grid, making me less accessible — behaving less like a ‘pastor sized church’ and more like a ‘big church’ where I led leaders. Overnight the vibe in our community shifted. People lost trust in my love and leadership — not simply in my competency (I am quite happy to admit that I wasn’t competently approaching the task). Instead of a human scaled solution we applied a variety of techniques; people were not people with names and stories, but cases to be managed by teams whose interactions were charted in a ‘customer relationship’ database.

Subsequently he writes:

“The Machine seems a Behemoth, a Leviathan, and it is. But it always manifests its own power at human scale, and that is the scale at which we must take its measure. Jacques Ellul once put it like this: We must not think about Man, but of my neighbour Mario… An anti-Machine politics, it seems to me, must spring from this older, grounded tradition. It should operate at the human scale, and not at the scale on which ideology operates…. A reactionary radicalism, its face set against Progress Theology, which aims to defend or build a moral economy at the human scale, which rejects the atomised individualism of the liberal era and understands that materialism as a worldview has failed us.”

I believe there is a kind of church that operates at this human scale; and that part of this is a differentiated approach to growth. My prayer is that God’s kingdom might grow; that many people might join the Lord of the harvest in fruitful life; experiencing the love of God for eternity — but this growth does not have to be subject to my control, or a ‘machine’ we build in our local church; it does not have to depend on technology or technique. It may come from embracing limits and encouraging others to embrace limits and to expand and duplicate in sustainable ways less reliant on technology, technique, and exhausting the human resources who are united to us by God’s Spirit as we act as the body of Christ together. It might emphasise rest and resistance not just output and productivity. It might take steps to not become big — to not act sizes above the present in order to ‘break through barriers’ and ‘reach more people’ but to steward the gifts and the environment we cultivate together in sustainable patterns that duplicate and give life, rather than joining the mechanical extraction of the natural and human environment that typifies the machine — strip mining all other local churches in the area to fuel your own vision and to add cogs to an ever-more-complex production for people to consume as they are consumed.

Church at a human scale actively resists ‘bigness.’ That’s counter-intuitive, I think, but essential. Before Against The Machine, Kingsnorth published a collection of essays Confessions of a Recovering Environmentalist. This included his essay ‘A Crisis of Bigness,’ in which he observed the failure of nations and systems that go beyond their capacity to operate well and so turn towards staying alive as an alternative to collapse. His thesis, following the work of Leopold Kohr who wrote The Breakdown of Nations in 1957, was that “wherever something is wrong, something is too big.” Kingsnorth asked, “what if big ideas are part of the problem? What if, in fact, the problem is bigness itself?”

Reading back over old vision documents from our machine church I ask myself the same question. Kohr argued that “small states, small nations and small economies are more peaceful, more prosperous and more creative than great powers or superstates,” I wonder if this is true of small churches?

“Socialism, capitalism, democracy, monarchy – all could work well on what he called ‘the human scale’: a scale at which people could play a part in the systems that governed their lives. But once scaled up to the level of modern states, all systems became oppressors.”

I wonder if this is true of megachurches, where, according to Keller, power centralises in the hands of the senior leadership (away from the congregation), and participation in the hands of employees, as growth happens (attendees consume and feed the machine).

“Kohr demonstrated that when people have too much power, under any system or none, they abuse it.”

This seems true of the countless stories of abusive megachurch leadership we read almost daily. Many of my own reflections on my experience were shaped by having trauma responses while listening to The Rise and Fall of Mars Hill.

For Kohr, “The task, therefore, was to limit the amount of power that any individual, organisation or government could get its hands on. The solution to the world’s problems was not more unity but more division.”

“To understand the sparky, prophetic power of Kohr’s vision, you need to read The Breakdown of Nations. Some of it will create shivers of recognition. Bigness, predicted Kohr, could lead only to more bigness, for ‘whatever outgrows certain limits begins to suffer from the irrepressible problem of unmanageable proportions’. Beyond those limits it was forced to accumulate more power in order to manage the power it already had. Growth would become cancerous and unstoppable, until there was only one possible endpoint: collapse. We have now reached the point that Kohr warned about over half a century ago: the point where ‘instead of growth serving life, life must now serve growth, perverting the very purpose of existence’. Kohr’s ‘crisis of bigness’ is upon us and, true to form, we are scrabbling to tackle it with more of the same: closer fiscal unions, tighter global governance, geoengineering schemes, more economic growth. Big, it seems, is as beautiful as ever to those who have the unenviable task of keeping the growth machine going.”

In my experience these words apply as much to churches as they do to nations.

I don’t want to keep growth machines growing any more — I would love to see more human-scale churches springing up to produce sustainable, life-giving communities as they embrace limits.