This is an amended version of a sermon I preached at City South Presbyterian Church in 2021. If you’d prefer to listen to this (Spotify link), or watch it on a video, you can do that. It runs for 37 minutes. This is the final sermon in the Revelation Series.

Revelation is like a good movie.

Throughout this series, as we have been looking at John’s apocalypse, his unveiling, I have been thinking about “The Wizard of Oz” and how when the curtains get pulled back, he is a bit of a disappointing little man with a machine.

And of course, our series title has a connection to the classic “Beauty and the Beast” – where the Beast was a guy who was cursed to become beastly until he could learn to love, and he loves the beauty, Belle, and is restored.

Today, I could not help but think of Disney’s “Tangled” – it is telling of the Rapunzel story; you might know it. Beautiful princess. Locked in a tower where her golden locks – her magic hair – becomes a ladder for prince charming. In Disney’s version, her golden hair is magical, and the wicked witch uses it to stay young and beautiful; she treasures this youthful vitality and guards this treasure by locking Rapunzel up in her tower. Until it all goes wrong for her and we discover what she really looks like. Underneath the magically beautiful exterior, she is a wicked witch. She is quite beastly.

You do not want to be on her team, or embrace her way of life. Rapunzel is the hero; the beauty.

Revelation is a bit like a movie – pointing its lens at all sorts of characters and inviting us to see life differently.

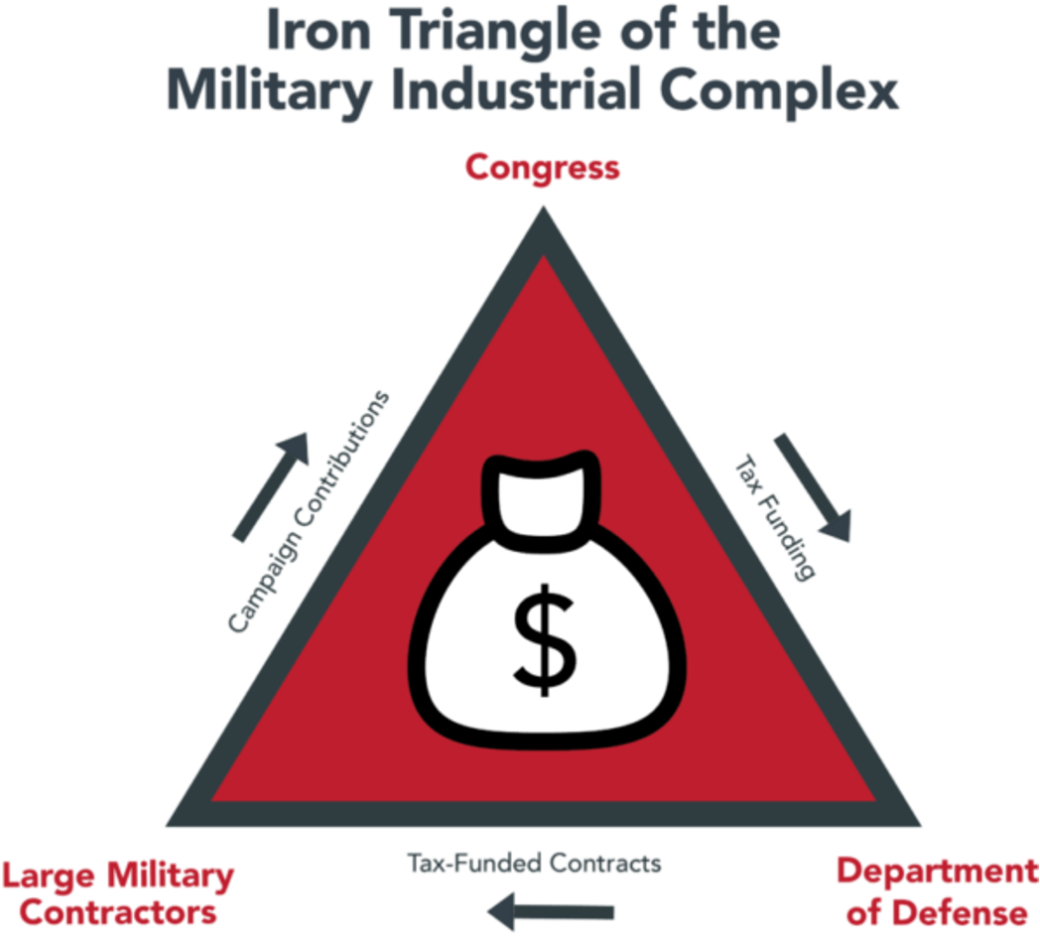

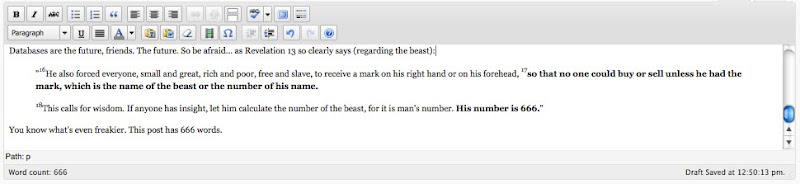

Its big focus is inviting us to decide what to worship – to see that our pattern of worshipping demons – spiritual beings – and the idols they use to corrupt us – and the political and economic systems these idols create, and the behaviors that this idolatry produces – violence, sexual immorality, theft, and magic arts – demonic spirituality (Revelation 9:20-21). Just remember this list because it will come up later. Revelation wants us to see these patterns are beastly, and to worship God as we see him revealed in the book instead (Revelation 14:7).

We have to choose between two kingdoms. Two heavenly cities.

God’s city, or Babylon. One rises and the other falls (Revelation 14:8).

From chapter 14 onwards, we start to see the downfall of the beastly city of Babylon – which is not the actual city of Babylon, it is picking up Old Testament imagery for the most beastly regime opposed to God’s people. The city of exile. The destroyers of the temple. The beast-worshipping enemies of God.

And it is inviting us to see other cities that share Babylon’s violent, greedy, idolatrous patterns as Babylons too. Babylon is the city of beast worshipping – and those who choose citizenship there face judgment; the “wine of God’s fury” (Revelation 14:9-10).

By the end of the book, it is clear Babylon the Great is not that great (Revelation 16:19). God’s judgment gets poured out. And the story invites us to choose our city; to choose our citizenship.

And we will see how Revelation unveils these cities – but it uses a pretty awkward metaphor to do it. It is an M-rated metaphor that draws, again, on the Old Testament…

Cities are not just presented as places to live – but as women who choose to use their bodies in particular ways as they choose who to become one with – the beauty of the lamb, or the beastliness of Satan and his beasts. So in chapter 17, we do not just meet Babylon, a city, but a great prostitute – who the kings of the earth commit adultery with (Revelation 17:1-2). An intoxicating temptress – just like lady folly in Proverbs; who leads the world astray with her intoxicating nature. The woman sits on the blasphemous beast – she is dressed as a royal queen. Purple. Red. Gold. Precious stones – she is a parody of the bride of Jesus we read about in chapter 21; the heavenly city (Revelation 17:3-4).

She holds a cup filled with abominable things; the filth of her adulteries.

The beast she is sitting on has seven heads. We will come back to that. Like the book said would happen, the beast’s name is written on her forehead. She is marked by Babylon (Revelation 17:5).

She is a beast worshipper, she has given herself to Babylon and has become one with Babylon – we are told she is drunk with the blood of God’s people; the ones who bore testimony to Jesus (Revelation 17:6).

So, if we are thinking cities, we have already met a city like this last week (Revelation 11:8).

This woman is sitting on a seven-headed beast, and those seven heads are seven hills (Revelation 17:9). Now, we have seen a bit of Rome in the background of John’s vision for first-century Christians – and Rome is a city famously built on seven hills. This woman has become one with Rome. Rome is Babylon the Great and it has marked her as his. And this woman who looks like a queen on the outside, is corrupt and beastly.

And the problem for this woman is that when the final conflict comes, Rome does not love her – the Beast does not love her – she is just going to get destroyed. Revelation describes this cosmic battle between Satan, the Beast, and his minions – and the lamb (Revelation 17:14). Things are going to be alright for the people of the lamb, because the lamb is Lord of Lords and King of Kings, and he just wins.

But they are going to be horrid for the woman. She is surrounded by all the peoples, the multitudes – the kingdom of the false king – but the beast – that Roman power – is going to turn on her and destroy her (Revelation 17:15-16). That is what beasts do. You play with beasts and you get exposed and devoured and burned up.

That is what beasts do. And now we get another decoding moment; the woman is the great city (Revelation 17:18).

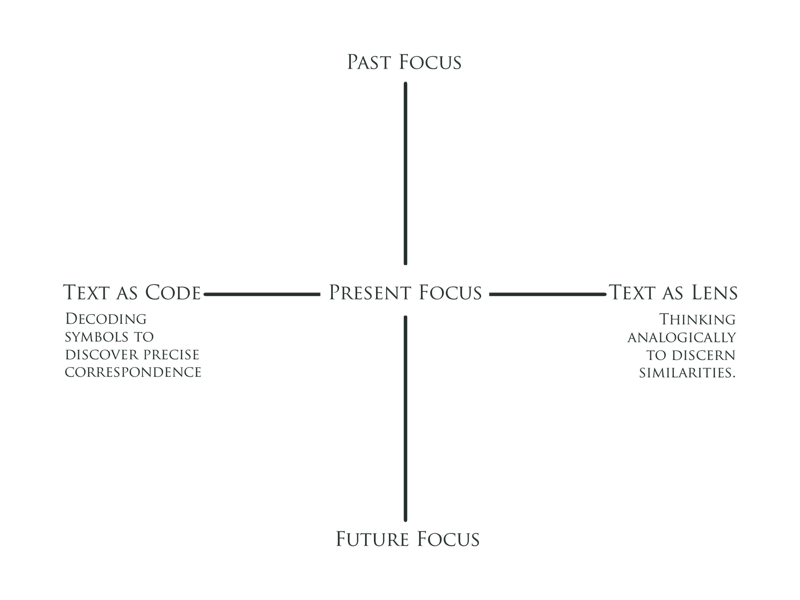

Now, there are three viable options here – I think – for what the great city is – Babylon is obviously a thing of the past when the letter is written, and these three are not exclusive – it could be all of them.

The first option is that the woman is the city of Rome, and the beast is the empire – but we have just been told the empire – the beast – hates and destroys the city.

The second option is that the woman is Jerusalem, and there’s some cosmic geography at play here where John is seeing the rule over the kings of the earth as a mirror of the lamb’s rule; idolatrous Jerusalem actually set the course for everyone else by rejecting Jesus. It became Babylon.

The third option is that it’s a lens that fits any city that opposes God in this way so that those caught up in its economic, political, and religious systems—like the kings of the earth—will be judged.

The unviable option, I think, is that it’s either a literal Babylon or a specific and particular future city way beyond the horizon of the original audience. I lean towards it being symbolic, and to John seeing all these so-called great cities coming together as Babylon—but also that this symbolism has to include Jerusalem because it is the city where Jesus was crucified. And that John is drawing on some pretty significant Old Testament imagery to condemn Jerusalem for being in bed with beastly Rome, and warning Jerusalem that Rome will turn on it and destroy it, because you can’t tame a beast.

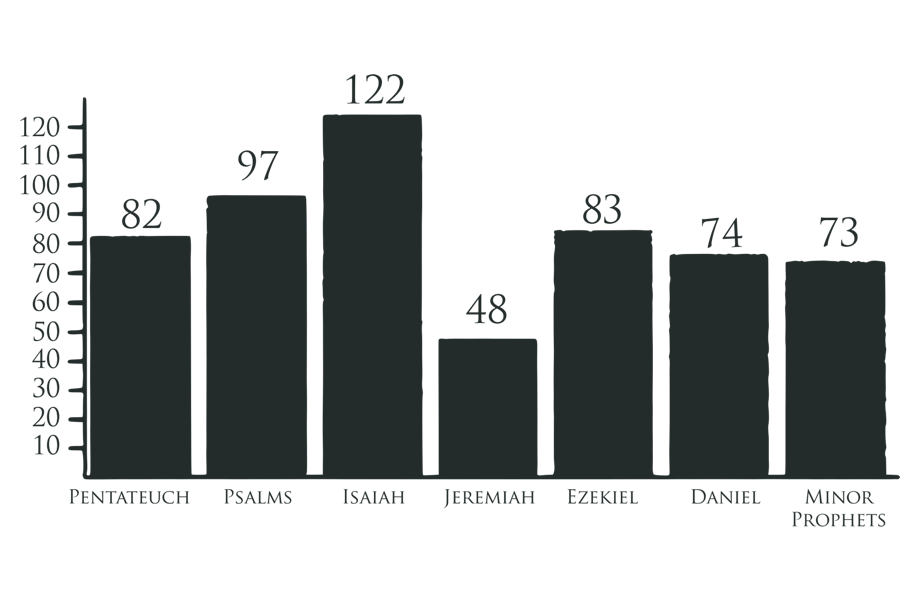

This idea that Jerusalem—and as a result—God’s people—become unfaithful and beastly Babylon—a prostitute—is found everywhere in the prophets.

Isaiah 1—the faithful city—Jerusalem—has become a prostitute (Isaiah 1:21).

Jeremiah 3—you—Israel—have lived as a prostitute with many lovers (Jeremiah 3:1). In fact, it’s both Israel and Judah—the two kingdoms within Israel—commit adultery with idols—idolatry is spiritual adultery (Jeremiah 3:9-10). In Ezekiel, the accusation against God’s chosen people is that they prostituted themselves to the beastly empires around them. Egypt, Assyria, and then Babylon—the land of merchants (Ezekiel 16:26, 28, 29). That’s interesting language that’ll get picked up in Revelation.

You might have wondered why I keep zeroing in on capitalism and the economy and greed here, when I’m talking about beastly systems not other things like sex—which is where we might feel like beastly regimes oppose God’s kingdom, it’s because economic realities—worldly wealth—seem to be at the heart of beastly power, while how we use our bodies and pursue pleasure is part of the package. Sexual immorality is part of the picture Revelation talks about. It’s wrapped up in an idolatrous grasping over the pleasures of this world. It’s the metaphor here of adultery, rather than faithfulness, but the lure seems to be about luxury and wealth and power rather than sexual pleasure.

And what could be a bigger example of Israel being unfaithful—jumping in bed with worldly power—than that scene we saw last week from the trial of Jesus; “we have no king but Caesar” (John 19:15-16). That’s from Israel’s religious and political leaders.

Well.

It’s all coming down. In this choice, Israel’s leaders chose the wrong city. The wrong empire. The wrong king. The wrong gods. In John’s vision, Babylon is over—it’s a dwelling place of demons and unclean things that must be destroyed (Revelation 18:2).

And it has pulled all the nations with it (Revelation 18:3).

And with the Old Testament background in the mix—this is exactly what the nations did with Israel.

Jerusalem was meant to be the center of God’s rule—the city that drew the nations in to discover God’s love, and wisdom, and peace, and blessing…

But instead, it’s a city where people conspired to kill God’s Messiah, as its leaders jumped into bed with the rulers of Rome.

“We have no king but Caesar…”

And again it’s wealth and luxury that is part of the pull for the “merchants of the earth.” And it’s all coming down.

These cities opposed to God will fall. They’ll be judged. And God calls his people to come out—to disconnect from Babylon—to avoid being swept up in her sins (Revelation 18:4); to not give our hearts and our bodies, to come out of the religious system of Jerusalem, and of Rome, and of any regime opposed to God.

And so to not receive the judgment that falls; plagues reminiscent of the plagues in Egypt—the Passover—the exodus—God’s people must come out and be created as a new nation; a kingdom of priests again. Or when it all falls down, it’ll fall on you.

What’s your Babylon? What kingdom or false god is pulling you from Jesus? It will topple. It will disappoint. It will come under judgment and will not stand. Come out. Flee.

This false city; this false woman; like Lady Folly she’s a false queen who will lead you to destruction in her pursuit of glory and luxury if you get intoxicated (Revelation 18:7).

She thinks she’s a queen, but she’s a wicked witch.

Her pride comes before a fall. Babylon is coming down. And when this destruction comes there’ll be weeping and mourning from everyone in bed with this beastly regime (Revelation 18:9). The kings and rulers, they’ll weep. They’ll come undone.

The leaders of the economy — the market — the merchants — those who get rich from idolatrous grasping of the things of this world — John gives a whole list of the things they buy and sell — gold, silver, precious stones, purple, scarlet cloth — all the stuff the prostitute dressed herself in as she jumped in bed with Rome — all the things that pulled her in. These merchants will be sad because the whole system comes crashing down (Revelation 18:10-11); with all the stuff they loved and put their hope in. Even the captains of their ships will mourn (Revelation 18:17). We met the beasts of earth and sea — here’s the people who get rich riding on their backs.

But the whole system crashes. The whole economic and religious and political regime comes under judgement; and it all gets revealed as hollow. Empty. A house of cards. It’s riches to ruin in an instant.

It’s exposed. It’s empty. Ruinous. Beastly.

Get out (Revelation 18:11). The city is collapsing — the important people. The wealthy. Those who create the idolatry that pulls people away from God — that leads beastly powers to kill God’s holy people… his faithful witnesses (Revelation 18:23-24). Revelation exposes this system. And it says God is coming as saviour and judge.

The great prostitute who has — by her corruption — corrupted the earth — leading the kingdoms of the world away from God, rather than towards God, has been condemned (Revelation 19:1-2). Revelation puts the lens on Babylon.

On Rome.

On Jerusalem.

On any false heaven and false city, and it says there is no life or future there….

Do not put your trust in princes or princesses. Do not put your trust in the market.

Do not be lured in by the bright lights of the cities of this world.

Do not give your hearts to that.

Do not be pulled there by your passions and desires and loves.

Life is not found there.

Babylon is coming down.

But the message of the book does not end with judgment on Babylon.

And a new kingdom is coming up, as a heavenly city comes down.

The false bride of God is going to be destroyed with her lover.

The real bride of God will come down.

The old Jerusalem is being destroyed to be replaced with a new Jerusalem.

And we have to choose.

The beauty or the beast. The prostitute or the bride. Because God’s victory involves a new bride. A new woman — not lady folly who leads to destruction, but the bright and clean glorious bride of Jesus, the lamb (Revelation 19:6-8).

The wedding of the lamb has come, and he is not marrying the prostitute riding on the back of the beast, but a new people… dressed in white, given by God, rather than the trappings of idolatry, bought from the merchants. But first we see the groom — the one who is called faithful and true (Revelation 19:11).

The one who rules with an iron scepter — this is the baby the dragon tried to devour — the one called the king of kings and lord of lords (Revelation 19:15-16).

This is Jesus — the lamb — but revealed in glory.

The serpent slayer. In Revelation’s climactic scene, the beast, the kings of the earth, all the powers and principalities opposed to God — Babylon in all its might — line up against the rider (Revelation 19:19).

And maybe we are used to the idea that spiritual warfare is evenly matched; that the forces of good and evil are held in some sort of delicate tension. Ying and yang.

Chaos and order.

Light and dark.

But they are not. The fight is a non-event. Babylon comes down. The beasts are chucked in the fire (Revelation 19:20). And it is not just the beasts, but the dragon.

Just when the battle lines are drawn and God’s people are surrounded — it is not a big battle like at the end of a movie. There is no moment when it could go either way.

Fire comes down and devours God’s enemies (Revelation 20:9-10).

The devil gets chucked into the fire with his cronies. The victory is breathtakingly fast and total.

The choice should be easy. Babylon or the new Jerusalem. Live like the harlot or the bride. Choose the beauty or the beast.

It is not a new choice; there is an Old Testament context here — this has always been the choice facing God’s people. Be God’s beloved bride, or be unfaithful. Isaiah describes God, the maker, the almighty, as the husband of Israel (Isaiah 54:5). Through Jesus, he invites the nations to be his covenant people too — his bride.

To be his covenant partners, like in Ezekiel (Ezekiel 16:8),

Clothed by God, beloved by God, dressed in fine linen by God (Ezekiel 16:10) — the vision we see again in Revelation 19 of the people of the lamb, dressed in white.

Israel is described as God’s beautiful queen, drawing the nations in on account of their beauty and faithfulness and relationship with God (Ezekiel 16:13-14).

We can choose to embrace this reality as the bride of Christ — the bride of the king — or be the beastly queen who gives herself to the nations instead of God.

The beauty, or the beast.

Choose who you unite yourself to — where you turn for metaphorical clothing, who gives you meaning and purpose and satisfies your heart, who you worship.

God, or the world.

The lamb, or the dragon.

This is the story of the Bible, but presented as a stark choice.

The prophets call Israel to return to faithfulness, to be the bride, because God is the husband (Jeremiah 3:14), but when Jesus, the bridegroom, turns up, they kill him.

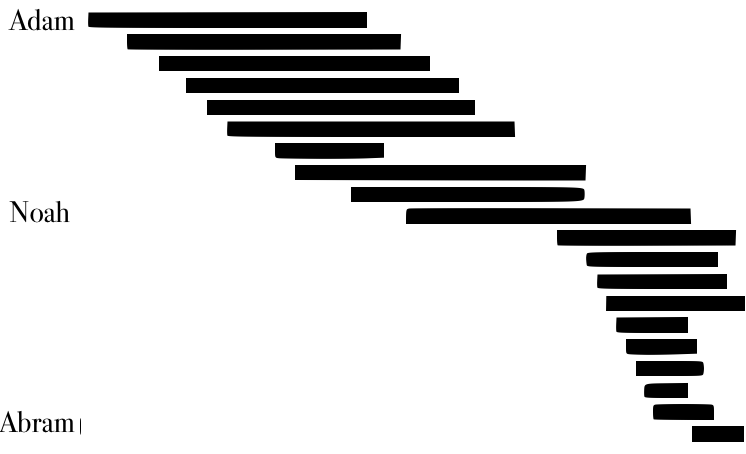

Jerusalem chooses judgment and God gives his kingdom, his presence, his Spirit, his glory, to those who accept the proposal. And those from Israel who recognize Jesus as king are returned and restored, while the kingdom expands to include the nations. The prophets long for a new Jerusalem in this moment of restoration. They see Jerusalem as the great city at the heart of the world. Jerusalem is meant to be the throne of the Lord, the meeting point of heaven and earth. The city all the nations come to to know God’s name and be healed, where they will receive new hearts (Jeremiah 3:17). And the prophets picture Jerusalem rebuilt by God as a city encrusted with jewels and precious stones (Isaiah 54:11-12).

And this is what John sees at the end of his vision, at the return of Jesus, the bridegroom, as he delivers this victory and destroys the beastly regimes and the dragon, Satan. As he reverses the curse and brings not just a new Eden but a new creation (Revelation 21:1). This is Genesis 1:1 all over again, only without the chaos sea in the picture. And in the new creation, John sees a new city, a new Jerusalem, a new woman, a bride prepared for her husband (Revelation 21:2).

Not a beastly woman, but a beauty. It’s a picture of the restoration not just of the peace of Jerusalem, where God dwelled in the temple, but the peace of Eden, where God dwelled with all humanity (Revelation 21:3).

The sad things are coming untrue.

The curse of Genesis 3 replaced with the blessing of Eden.

It’s a happily ever after. The victorious king killing the dragon and uniting with his princess in love forever (Revelation 21:4). It’s restoration and recreation without the threat of the serpent or anything that might pull us from God, because Jesus is the victorious king, and God, the almighty, is reigning unopposed (Revelation 21:5).

The victorious Jesus comes to give life to his people, satisfying our thirst, fulfilling the desires of our hearts that leave us drinking from all sorts of other wells.

I can’t help but think, in this moment, of the woman by the well in John’s Gospel, the woman who meets Jesus and suddenly finds what she’s been looking for so that she is restored to life (Revelation 21:6).

That woman is us, if we also come to Jesus like a fairytale princess coming home to her beloved king. But those who choose Babylon and idolatry, they are shut out; all those demonic idolatrous practices, we saw this list before, to live that way is to choose the beast, to choose Satan, and to choose his destiny (Revelation 21:8).

Destruction. This is what happens to those who worship the beast and its image (Revelation 14:9-10). Those who choose the beast, like the prostitute of Babylon, and live in his city.

And so we meet the new bride, the restored Jerusalem, the city of God. And we’re invited in (Revelation 21:9). It’s a city that has all the beauty and riches that pulled the unfaithful woman, the idolatrous people, away from God. Fake heavenly cities echo this real deal.

It’s a city that fulfills the vision of the prophets. Isaiah with a city covered in precious stones (Isaiah 54:11-12, Revelation 21:10-11). And even Ezekiel, which sees these same jewels as echoes of Eden, the garden of God on his holy mountain (Ezekiel 28:13-14, Revelation 22:1-2).

And John is picturing Eden restored with this jeweled temple, and the river of the water of life surrounded by the tree of life, where God dwells.

The choice is stark, choose between the city of destruction that will be destroyed; all its worldly riches, and idols, and violence.

Or choose the city of life, the new Eden, and the presence of God, and living water, and beauty and glory.

Choose the false city and its false gods, and Satan behind the curtain pulling the strings, and share in its fate, his destruction. Or choose the city of the lamb, and share in his life (Revelation 20:10, 21:8, 22:1-2).

Choose to be the ugly witch in the story who destroys others for her own sake.

Or to be the princess, to join together with our king forever.

So there are two imperatives from all this.

First is to come out of Babylon (Revelation 18:4). Don’t give your heart to idols. To wealth. Power. Sexual immorality. Pleasure. Figure out how to not live as citizens of a city opposed to God, a beastly regime. Refuse to bow the knee to the beast, don’t share in its sins.

And come in. Come into God’s new city. Become the bride (Revelation 22:17).

That’s the message of Revelation. It paints the choice facing all of us in stark relief.

It exposes life as it really is, not just the desires of our hearts, and where they take us, but the nature of those who offer to satisfy these desires and the kingdoms they create.

And we have to choose, worship Satan, chase the things of this world, chase life without God, become beastly and be destroyed.

Or worship Jesus, take your thirst, the desires of your heart to be known and loved and satisfied, to him, and receive life as a free gift forever. The beauty or the beast.

Which will you choose?