“Fairy tales do not tell children the dragons exist. Children already know that dragons exist. Fairy tales tell children the dragons can be killed.” — G.K Chesterton

“Mythology is not a disease at all, though it may like all human things become diseased. You might as well say that thinking is a disease of the mind” — J.R.R Tolkien, On Fairy Stories

We are, throughout, in another world. What makes the world valuable is not, of course, mere multiplication of the marvellous either for cosmic effect… or for mere astonishment, but its quality, its flavour. If good novels are comments on life, good stories of this sort (which are very much rarer) are actual additions to life; they give, like certain rare dreams, sensations we never had before and enlarge our conception of the range of possible experience. Hence the difficulty of discussing them at all with those who refuse to be taken out of what they call ‘real life’ — which means, perhaps, the groove through some far wider area of possible experience to which our senses and our biological, social, or economic interests usually confine us — or, if taken, can see nothing outside it but aching boredom or sickening monstrosity. They shudder and ask to go home.” — CS Lewis, On Science Fiction

“Most people think of games as power fantasies—escapism that makes people feel heroic and accomplished. That Dragon, Cancer has the opposite effect.” — Drew Dixon, That Dragon, Cancer teaches players to long for renewal amidst defeat

A video game made me cry.

I cry at the drop of a hat these days; well; I feel like crying at the drop of a hat. But this game pulled me in and then kicked me in the feels. It’s called Fallout 4. You might have heard of it. But. Be warned. There be spoilers.

Actually. Two video games made me cry. The one that really had the tears flowing — that didn’t just kick me in the feels, but headlocked me and threw me into some sort of MMA style submission hold — is an independent release called That Dragon, Cancer.

Why did these games make me cry? They have a couple of things in common — both games take place in beautifully rendered, coherent, worlds. These environments are the product of the sort of mythopoeic world-creation that’d have both C.S Lewis and J.R.R Tolkien feeling pretty excited about the capacity for video games to get us in touch with the enchanted reality we really live in. Both games rely heavily on story-telling; we’re carried along on a journey that pulls on the heart strings quite deliberately — even though Fallout 4 is in a sandboxy open world where you’ve got some freedom, while That Dragon, Cancer requires you to click your way from A to B in a very linear manner. Both games — and here’s the rub — hit me in the feels because of what they do with parenting, and loss. Though there’s also a stark difference here which made the impact of That Dragon, Cancer longer lasting for me; in that it is the real story of creator Ryan Green, and his wife Amy, and the loss of their beautiful son Joel. It’s an enchanting story because even amidst the clinical science and the very raw, real, emotions on display from the Green family, and others who’ve battled the dragon, there is a sense that Joel’s story plays out against a transcendent backdrop. This life, this cancer, is not all there is — it’s a dragon to be fought as part of a bigger, spiritual, narrative that is much bigger than simply the Greens versus a horrible and confronting bunch of aggressive cells.

Fallout 4 is pure post-apocalyptic fiction told in a completely ‘immanent’ frame. There’s no real ‘enchantment’ here. Just the ability to explore and craft your way to recovery, building villages for survivors of the nuclear apocalypse while hunting for your abducted son, Shaun. Everything is very ‘tactile’ in a sort of digital way. You scrounge through debris looking for duct tape so that you can upgrade a weapon; you can salvage components from just about anything to use it to build your settlements or upgrade your mechanical armour. I can’t walk into Bunnings or the hardware aisle of a department store now without subliminally thinking ‘jackpot.’ Everything is subject to the laws of cause and effect, and you’re the author of your own destiny. You’re, as you play, in control of your story. The one spanner in the works is that it turns out Shaun was pulled from the grasp of your murdered wife a significant number of years before you’re cryogenically defrosted, many more than you thought, and he’s much older than you. He’s the game’s ‘father’ figure; and now the head of the potentially nefarious ‘Institute,’ the organisation responsible for his abduction and your wife’s death. What you do with this information, and with Shaun, changes the course of the game.

Image: “I, Father, am your son” — an awkward reunion in Fallout 4

My virtual self was convinced of the evils of The Institute, and pretty upset that Shaun wasn’t the little kid I’d been searching for; so I shot my son. For the greater good. My finger hovered over the trigger button for quite a while. This was the sort of ethical dilemma that video games now confront us with as they draw us into their worlds — into their ‘narrative frames’ — I shot ‘father’ because any relationship I thought I had with the character was based on lies. He was a manipulator, and his organisation was a threat to the better vision of the future that I was building in the Fallout 4 world. But I felt conflicted doing it.

It helped that the Fallout world is both purely digital, with no real world crossover, and purely immanent — the consequences of my actions were going to change that world, but the flow on effects would only be in the chain of causality in the ‘immanent’ world, there was no cost to my digital soul because in the post-apocalyptic rubble there’s very little room for faith. Those of faith were members of strange post-doomsday doomsday cults. The landscape is littered with abandoned churches that at best are home to a few post-human irradiated ghouls. I wore a clerical robe for much of my time wandering through the landscape, but the hope I brought came from slaying mutant cockroaches and liberating civilians from the grasp of some over-sized mutants. With a custom-made automatic shotgun.

Fallout’s world is our ‘disenchanted’ reality on steroids. This little paragraph from Dreyfuss and Kelly’s All Things Shining a philosophical treatise on the evacuation of ‘meaning’ and lustre from post-modern life, could easily describe the sort of world you inhabit as your character. There’s nothing remotely shiny — physical or metaphorical — about the Fallout world.

“The world doesn’t matter to us the way it used to. The intense and meaningful lives of Homer’s Greeks, and the grand hierarchy of meaning that structured Dante’s Medieval Christian world, both stand in stark contrast to our secular age. The world used to be, in its various forms, a world of sacred, shining things. The shining things now seem far away.” — Hubert Dreyfuss & Sean Dorrance Kelly, All Things Shining

Fallout didn’t end up teaching me much about myself; I enjoyed the scavenging and building of settlements for others more than I enjoyed picking which faction to side with in the bid for some sort of restorative revolution. I felt things about the loss of my son — while pursuing him — but when confronted with the reality, I made a very ‘immanent’ decision; one that benefited my digital minions and my wasteland idealism. One that fit my nobel cleric’s vision of the end times best. I just wanted my people to live another day… so when that happened, I was happy. Happy enough to hang up the shotgun, which I named THE DELIVERER, and start pottering around in my settlement with a robotic barman.

That was Fallout 4. Perhaps the perfect story — or at least ‘a’ story — for the disenchanted ‘secular’ age; where transcendent questions are secondary. That Dragon, Cancer is the reverse. The ‘sciency’ immanent questions are very much the present reality, but there’s something bigger at play. A dragon that needs killing. A dragon we’d like to see killed, as fellow citizens of this world.

“Fear is cancer’s preservative. Cancer’s embalming oil. You’re a snake. A serpent. A dragon with snuffed out coal on his breath. Melting.”

“Whenever I ask sciency questions I nod my head. Digesting every Latin word, hoping it will stick to my ribs, become part of me. That if I ask enough questions, that maybe I could get my brains around this cancer.”

If only cancer could be killed simply by understanding it. If only we could think it gone.

It’s unclear to me still whether That Dragon, Cancer has a happy ending. Joel dies. You know that from the beginning. From the marketing. You’ve got to be prepared to ride that rollercoaster with the family before investing yourself. Joel dies. And yet. He lives. And not just in digital form — though it’s beautiful that Ryan and Amy were able to ‘incarnate’ and preserve Joel’s memory in the bits and bytes of his story in a lasting way. Joel lives because Joel’s family put their faith in Jesus. Joel lives, waiting for that time when Jesus returns to slay the dragon once and for all.

I can’t remember the first time I fell apart while playing. Joel’s polygonal face in game play very readily blurred into the visage of my son. I was destroyed by empathy with every click, as I moved through the journey from early stages, to treatment, to diagnosis, to prognosis, to desparate fight, to Joels’ death. One of the big moments for me was the moment you see Ryan’s immanent world collapse. The moment where asking all the great science questions in the world isn’t going to cut it. The moment where the immanent world collapses, or can’t support us, and we’re left grasping towards the transcendent, and really asking “where are you God?”, “where are you when kids like his, maybe like mine, are getting cancer?”

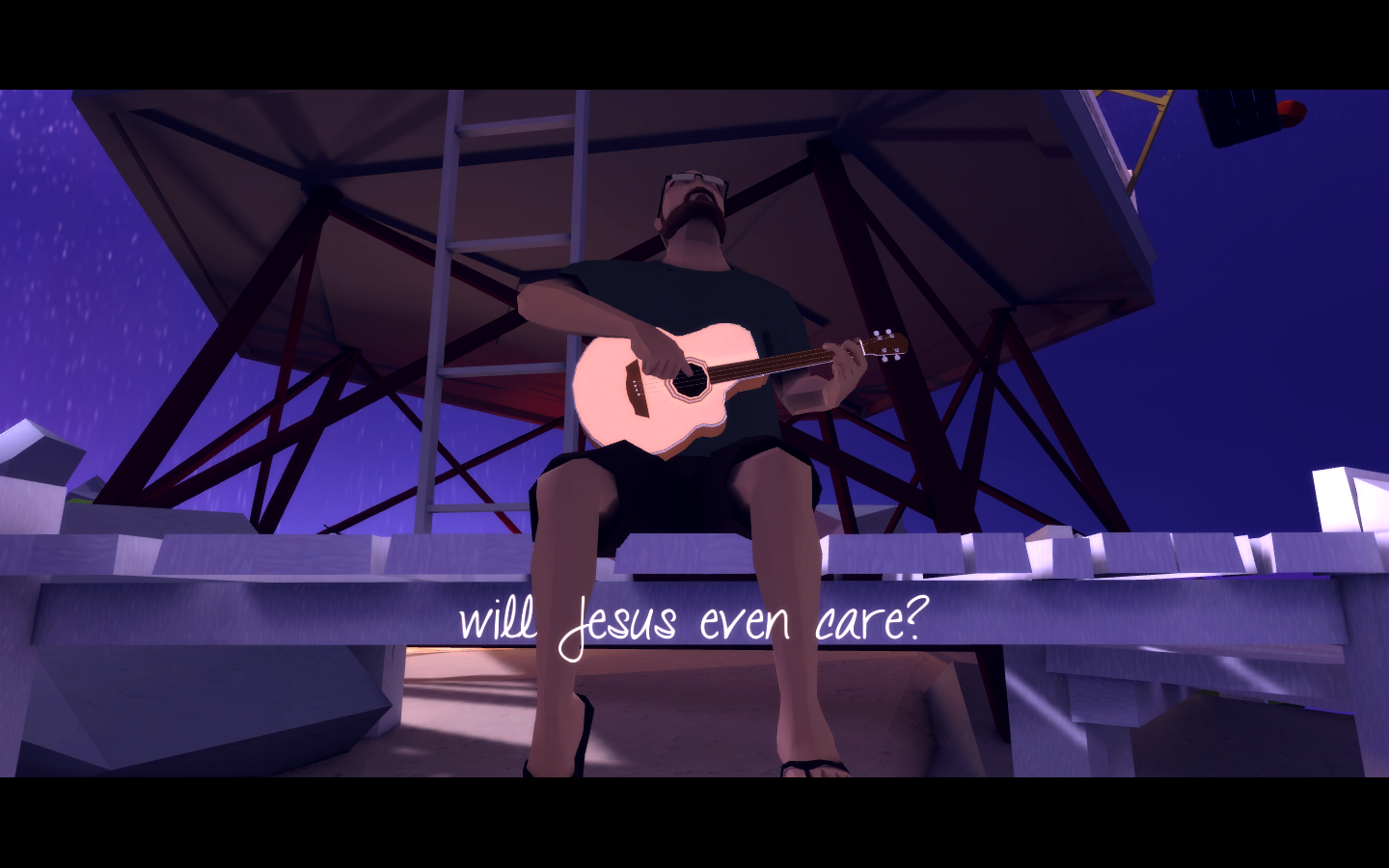

Does God really care? Or as Ryan asks at one point:

“If Joel does die, will Jesus even care? Will he weep for him? Or for me? I think greater than my fear of death, is my fear of insignificance.”

Ryan and Amy ask those questions. And carry us with sensitivity and beauty and grace through their journey towards answering them. They don’t find all the answers, but they find reason to hope. They find meaning in faith — not just in the latin names of Joel’s dragon-like cells, or in the treatment. They find beauty in moments of pain, and things to be thankful for. They are amazing, and though they’re a world away I love them for it; and I long to spend at least some of my eternity with them and their pancake-loving son. Their story enchanted me. Here are some of the closing words from Amy to Ryan. I know I lost it at this point — I know it made me confront the ‘dragon’ and shake my fist at it, and its master death and Satan. I know it made me place more of my hope and trust in the one who will end the dragon’s grip on this world.

“So here we are. And the air is emptier without his laugh, and yet our hearts are still full, though with a different drink. And this ride we’ve been on for so long is silent. And so also is the Lord. And so we sit here in this new silence. And long for the noise to start again. And long for the music to start again, and for the disc to spin again. Even if it means going round and round for many more years. For at least we would be moving and Joel would be laughing, here on earth. And not only in heaven. I sense that his silence is only because he is drawing his breath. And now we know love and longing, empty and full, all in one moment. And I am grateful that we loved him well. And that we miss him well.” — Amy Green, That Dragon, Cancer

We’re waiting, with Ryan and Amy, Joel’s parents. Waiting amidst pain. Waiting in longing. Waiting in hope. Waiting for that day when Joel’s ‘words’ at the end of the game become reality — “you made it too“… Waiting for our faith to become sight.

And I’m glad they’ve shared some of their waiting with us, and all of their faith, and hope, and love for Joel, and their abiding trust in Jesus through the pain. I’m glad I ‘played’ my way through their story, and that my world was expanded by their experience — by Joel’s love for water, and ducks, and dogs, and pancakes, and by his family’s love for him. I love the final scene of the game — an imagination of reunion. Final reunion. A picture of Joel in the new creation. Cancer dead. Family restored. It’s more compelling than the reunion in Fallout, and ultimately, despite the multi-million dollar difference in budgets for rendering the world — and despite the pain being real — I’d rather live in Ryan and Amy’s world, which is more vivid and real, than in Fallout’s post-apocalyptic flatness and grey. I’d rather face these real questions — real pain, real mess, than that moment — real or virtual — of indecision about what preferred immanent solution I want to pursue with the pull of a lever, or a trigger, as I seek an effect I might cause. I’d rather live in an enchanted world than a disenchanted world where only ‘scientific’ questions have any bearing on the future of my family. I’d rather not feel like I’m in control — because I have no answer in the face of tragedy if I am. I can’t slay the dragons in this world on my own.

So why does this matter? Why overthink video games — no matter how profound — in this way? Stories matter. The worlds our stories occupy matters. Because we’re shaped, profoundly, by story. Especially stories we participate in — which gives video games incredible power. This quote from James Smith could well be contrasting the approach to the world found in Fallout 4 and in That Dragon, Cancer.

“Instead, we should say that we have a “feel” for the world that is informed by stories that dispose us to inhabit the world as either a bounteous but broken gift of the gracious Creator or a closed system of scarcity and competition; and as a result, either I will just “naturally” be disposed to see others as neighbors, as image-bearers of God, whose very faces call to me in a way that is transcendent, or I will have a “take” on others as competitors, threats, impositions on my autonomy.” — James K.A Smith, Imagining the Kingdom

Fallout 4 relies on the premise that you can be totally in control of everything — put the right machines together, make the right choices, control the world and your environment just right — and you’ll live, not just you, but the society you’re building. That Dragon, Cancer makes it clear this promise is a baldfaced lie. It doesn’t matter how good you are at pulling levers, or knowing stuff — the monster will take down the machines every time. Hope is found somewhere beyond the machine. These games and their questions of loss, and children, and control, are interesting examples of the two ways of seeing the world and ourselves that Charles Taylor talks about in A Secular Age and James K.A Smith summarises for us in How (Not) To Be Secular:

“It is a mainstay of secularization theory that modernity “disenchants” the world — evacuates it of spirits and various ghosts in the machine. Diseases are not demonic, mental illness is no longer possession, the body is no longer ensouled. Generally disenchantment is taken to simply be a matter of naturalization: the magical “spiritual” world is dissolved and we are left with the machinations of matter. But Taylor’s account of disenchantment has a different accent, suggesting that this is primarily a shift in the location of meaning, moving it from “the world” into “the mind.” Significance no longer inheres in things; rather, meaning and significance are a property of minds who perceive meaning internally… Meaning is now located in agents. Only once this shift is in place can the proverbial brain-in-a-vat scenario gain any currency; only once meaning is located in minds can we worry that someone or something could completely dupe us about the meaning of the world by manipulating our brains… There is a kind of blurring of boundaries so that it is not only personal agents that have causal power Things can do stuff.” — How (Not) To Be Secular

Fallout 4 and its world of things and control — even its ‘hauntedness’ — is set in a secular world. Even the disease — and the very visible scarring of people and ghouls — is the result of the nuclear apocalypse. That Dragon, Cancer presents us with the reality that the world is broken, and asks ‘is there more to this disease than we might grapple with via science’… these stories, these worlds, leave us with a very different understanding of ourselves, and our limits.

At this point Taylor introduces a key concept to describe the premodern self: prior to this disenchantment and the retreat of meaning into an interior “mind,” the human agent was seen as porous. Just as premodern nature is always already intermixed with its beyond, and just as things are intermixed with mind and meaning, so the premodern self’s porosity means the self is essentially vulnerable (and hence also “healable”). To be human is to be essentially open to an outside (whether benevolent or malevolent), open to blessing or curse, possession or grace. “This sense of vulnerability,” Taylor concludes, “is one of the principal features which have gone with disenchantment”… So the modern self, in contrast to this premodern, porous self, is a buffered self, insulated and isolated in its interiority, “giving its own autonomous order to its life” — How (Not) To Be Secular

My character in Fallout 4 was most definitely buffered — protected by his isolation, never getting too close to those in the settlements, separated from the world by my mech-suit, totally and symbolically insulated and isolated from the nuclear affects of the world. Even my pet dog was called ‘Dogmeat’ — perhaps to prevent any sort of attachment. Totally buffered. Totally autonomous. Totally in control — which is, ultimately, why I shot my son. Because I preferred my own ‘ordering’ of the world to his proposal, and wasn’t going to sign up. While the Greens, in That Dragon, Cancer couldn’t be buffered even if they tried. They didn’t just have to be completely open to some sort of transcendent blessing amidst their vulnerability, in making the game and consciously ‘unbuffering’ — both seeking contributions from other affected families, and involving ‘players’ like me in their story — they’ve remained vulnerable and connected. There’s a real path towards healing for them. Not in terms of tackling the dragon — Jesus will ultimately do that, and science might help along the way. The path to healing is one consistent with a transcendent world, and the picture of the enchanted, and enchanting, future we see in Revelation. What I’ve really learned in these games, as I’ve played, is that when you’re being beaten and buffeted about by what life in this world throws at you, an unbuffered self actually, counter-intuitively, has more to protect it than the buffered self. We aren’t in control. We need others. We need hope. We need transcendence. We need more than what ‘is’ in this material world. More than Dogmeat, or friendmeat. We need a dragon slayer.

“Then I saw “a new heaven and a new earth,” for the first heaven and the first earth had passed away, and there was no longer any sea. I saw the Holy City,the new Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God, prepared as a bridebeautifully dressed for her husband. And I heard a loud voice from the throne saying, “Look! God’s dwelling place is now among the people, and he will dwell with them. They will be his people, and God himself will be with them and be their God. ‘He will wipe every tear from their eyes. There will be no more death’ or mourning or crying or pain, for the old order of things has passed away.”

He who was seated on the throne said, “I am making everything new!” Then he said, “Write this down, for these words are trustworthy and true.” — Revelation 21:1-5