From time to time I write about preaching. The stuff I write about preaching isn’t necessarily going to be all that interesting to you (and sometimes these posts blow out in length), but preaching is what I get paid to do, so it probably pays to think about it sometimes, and it’s nice to be able to look back on how my thinking has developed over the years.

This is a post about preaching, and more than that, it’s a review of a relatively academic book on preaching, Preaching As The Word Of God: Answering An Old Question with Speech-Act Theory by Sam Chan. This is a very important book on preaching, and if thinking academically about what preaching is, or having a thoughtful academic approach from an academic/practitioner transform your practice sounds like a good thing, then you should read the book before you read the rest of this review.

It might help to think of the question at the heart of this book as the question of whether preaching is like holding up a cricket ball to be examined and understood, or as like bowling a ball with intent. That might help when we get into what speech-act theory is all about.

A primer on how/what I thought about preaching before this book

I read lots of book reviews; and write a few. I have a personal bugbear with book reviews that assess a book through some sort of unacknowledged/unexplained bias and or system; and I have issues with book reviews that don’t seek to use the thing they’re reviewing as a conversation partner; that simply assess a book through a grid and don’t look at how the book might modify the grid, or the grid might modify the book, a good book review — a review essay — takes readers somewhere new because it’s a re-mixing of the ideas of the book through the head of the reviewer. Those are fun. That’s what this is, and it’s what I hope to do whenever I review a book, or I can’t be bothered…

Sometimes I review preaching books like The Archer and The Arrow, Hearing Her Voice, and Saving Eutychus, and I use these books as opportunities to extend the conversation (and my own thinking) about what preaching is (or at least what our churches try to do on a Sunday). I wrote my Masters thesis on persuasive communication and how to do it ethically as well; this was about more than preaching (in that it was about public Christianity), but it also provides a lot of my framework for preaching and thinking through books like this. I’ve touched on it in posts about how ethos, pathos, and logos all need to be part of our preaching, and also about how ‘word ministry’; or the proclamation of the Gospel, is not just the spoken monologue, but can include singing (including the non-verbal communication bits (our pathos and ethos) both music and movement) and other media. I say all this, and link to all these, because nothing appears in a vacuum. I’m about to engage with a new book on preaching, and it’s worth declaring what my assumptions/framework are up front. Here are some of the things I thought about preaching before reading this book, in sum.

- Preaching is preaching (the Greek κηρύσσω) when it is the proclamation of the Gospel of the crucified and resurrected Lord Jesus. Other forms of public speaking are not really preaching, because the preacher acts as the herald of the king. There might be other types of speaking that Christians engage in in public.

- Preaching is a corporate act of the gathered body of Christ (ala 1 Corinthians 12) no matter which individual speaks, all are speaking (and engaged in the act) just as when I make words with my mouth, my lungs, vocal chords (and hopefully brain) are engaged. It’s not the act of a special ‘set apart’ priestly mouthpiece from God who speaks to the people of God. It is for both believers and unbelievers because the Gospel is what both believers and unbelievers need to hear (with slightly different rhetorical ends, but it is possible for one piece of communication to say more than one thing to different people at the same time).

- Preaching is tied to who we are as the church — we are the body of Christ, we are the bearers of his image in the world (and image bearing is a vocation tied to representing the name and nature of God and his kingdom in his world), and we are ambassadors for Christ and ministers of reconciliation between humanity and God (2 Corinthians 5).

- Preaching is one of the things the church does, along with the sacraments, as the essential function of the church in the world, and the church for the church. The sacraments are also essentially preaching (just with more than words, ala 1 Corinthians 11:26), and it is possible that preaching is essentially the same as the sacraments because, basically, when we gather in the name of Jesus, Jesus promises to be there.

- The authority behind any preached word comes from God’s word (it’s that we proclaim), it is the proper explaining of how God’s word in the Old Testament is fulfilled in Jesus, and how Jesus being Lord shapes the way we live now as the people of his kingdom. It also comes from the role of the Church, and via the work of the Spirit. It isn’t human authority, and it isn’t in the hands of an individual, no matter how persuasive they are.

- Preaching involves words, but it also draws on (and draws credibility from) the life of our community-in-the-world, and the life of the speaker-in-the-community (our ethos), and our ethos is to be shaped by our message if we want to preach ethically and with integrity. You can’t have words without an ethos helping those words be interpreted and persuasive any more than you can have ‘the word of God’ without the God who speaks. Separating logos from ethos is like trying to separate the persons of the Trinity. Our message is Christ crucified for us, sinners. We preach as sinners being reshaped by the message of the Cross (a message that represents God’s power, but is weak in the eyes of the world). Part of our ethos and our pathos will involve the connection of our words to communication mediums that support the message and help produce an appropriate emotional response, not simply an appropriate rational response (and the medium is the message, so good preaching-as-communication involves thinking about what the best medium to effectively carry our message is, and what mediums (like singing) might support other mediums (like speaking) so that the body might preach Jesus together employing a range of gifts and methods).

- Preaching also, in order to be effective communication, involves some sort of listening to God (in his word, that we’re aiming to preach), to the people we speak to — outside the church in order to understand the barriers to the Gospel, and in the church in order to understand where the pull of ‘false gospels’ is being felt, and where people need reassurance and encouragement.

These are the basic assumptions I brought with me as I read Sam Chan’s new book on preaching.

A brief overview of Preaching as the Word of God

Like me, Sam Chan thinks preaching is a really, really, big deal. This relatively recent book (based on an older dissertation) takes the reader through what the Reformers, specifically Luther and Calvin, believe about preaching, what the Bible suggests preaching is from the Old Testament to the New, and then gets super fun using speech-act theory to support his conclusion that when preaching really happens (according to a defined set of parameters), God is speaking. When we preach, according to certain criteria, God speaks. Preaching is God’s word.

I like it. I mean, I guess I’ve just outlined a framework where this idea seems relatively uncontroversial. And while there are certain bits of that framework that don’t necessarily get a run in the book, the book doesn’t contradict any of them (as far as I can tell), and I’ve been bouncing some of these ideas back and forth with Sam since finishing the book. But what I really like about the book is not so much the stuff that agrees with what I already thought… no. I like the implications of the way Sam gets there; via the Reformers, the Bible, and speech act theory, some of the stuff he suggests should change how we approach not so much the content of preaching, but the delivery, our intention, and our understanding of what is happening (and of our responsibilities as speakers and hearers). Now. The book is relatively academic, but it’s a fruitful read (and a challenge) for anyone who preaches or wants to be a preacher… since I don’t have any major disagreements with its thesis; indeed, I wholeheartedly agree… so rather than reviewing the book the ‘old fashioned’ way and telling you what it says, I’ll explore some next steps in the conversation from my own dabbling with speech-act theory in my thesis. Sam has been pretty generous as a dialogue partner online so I have some sense that he’s at least intrigued by where this stuff goes… but he’ll, like anyone, have right of reply here.

It’s worth saying that in a year where lots of people are wanting to celebrate the Reformation, preaching was a really big deal in that movement… and preaching of a particular sort. Gospel preaching. And this book is a worthwhile reminder that Gospel preaching isn’t just incidental to the life of the church; in some ways it is the life of the church. One of the things that struck me about Luther as I read his works during college, and again as I read Sam’s book, is that if anything Luther held the preached word as more important than the other sacraments (and I use those words provocatively and deliberately to suggest that Luther essentially treated the preached word as a sacrament where God is present in preaching in much the same way as he is present in the bread and wine). This book is a bracing picture of what preaching could and should be if we approached it in the Spirit of the Reformation, the Spirit of the New Testament, and, arguably, necessarily, in the Spirit of Jesus. Cause it’s ultimately the same Spirit.

What is speech-act theory?

So let’s do a bit of a breakdown of Sam’s argument here and some of its implications. First, it’s handy to get a little bit of a primer on speech-act theory. It’s a theory that when you first hear it, especially as a Christian, just seems relatively obvious. Words do stuff. Spoken words are actions that achieve results (wedding vows are a good example). Separating word and action doesn’t really work in our experience of the world (I’d argue for an Act-Speech theory too… that actions can communicate things, that we as images communicate by being and doing… but that’s far beyond the scope of this piece and you should read my thesis to get some of the thinking there). A ‘speech act’ performs something… in some sense it creates a reality, whether it’s a promise, a proclamation, an order, an invitation, a warning, a thanking, or a greeting (this isn’t an exhaustive list).

Sam does a really helpful thing of regularly summarising his argument so that you stick with it all the way through; what follows under these headings are the numbered summaries of his argument from the book, but I’ve split them into the component parts of a speech act, and then responded a little to advance the conversation (either by agreeing and considering implications, or positing some alternatives to consider).

The Locutor: who speaks on God’s behalf; or who speaks on God’s behalf?

1. God is a God who speaks his word.

2. God raises, commissions, and sends human messengers to speak on his behalf.

3. These human messengers are anointed, gifted, and empowered by the Spirit, who is the author of the word of God.

This whole speech-act thing is great, and these three points are foundational to the argument — but I want to broaden them a little bit… because where Sam goes here is basically to say that the individual preacher has this particular role in and for the church (and that the church is part of commissioning the speaker as a preacher); he suggests that preaching is an individual function, and certainly, in a descriptive account of what happens in our church services where the ‘preaching’ happens, this is true. There is a preacher, and they play this role, and hopefully they’re gifted… But here’s where I want to tweak things slightly — to suggest preaching is a corporate function of the body (working together in its various parts).

What if the ‘human messengers’ commissioned to speak on God’s behalf are coterminous with ‘the church’, that this commission is corporate, not individual; so it’s the body of Christ, which is ‘anointed, gifted and empowered by the Spirit’ and when the one speaks in our gathering, as the ‘mouthpiece’ they speak for the whole body; as part of the body, appointed by both God and the body to speak in this way; so ‘preaching’ shouldn’t just be seen as the job of the preacher, but of the body; and this is a bit of a game changer, because if we conceive of preaching in reformed terms, as Sam wants us to, we conceive of it not as a priestly act of a priest, but as a (even ‘the’) priestly act of the priesthood of all believers; which means the preacher isn’t detached from the body to speak to the body from God, but is, as part of the Body, speaking God’s word to the body and to the world the body is ‘incarnate’ in… which, in practice, means the preacher not thinking of themselves as a specially called individual — God’s gift to the church — but as the person appointed by the body to speak on its behalf and for its good. The ‘body of Christ’ is given life, and nurtured, by the word of God and this nurturing happens, in part, through preaching.

A corporate model like this changes, for example, the way the preacher conceives of their task; the task becomes to listen carefully to God’s word, but also to listen carefully to the body (in order to speak corporately). This challenges an evangelical practice where preaching is essentially priestly in a pre-reformation sense; a special commission some how set apart from the life of the body, not from the life of the body. The preacher speaks the word of God, certainly, but it’s like they get amputated from the body of Jesus to do so, and then turn around and speak back to the body. In a practical sense the way this priestly thing works out is that the preacher sees their primary job as speaking for God to the body; rather than speaking God’s words as the body to the world (actively listening to other members, being supported in prayer, expertise, and the enrichment that comes from multiple perspectives from different ages, stages, and experiences of life), and also speaks God’s words to the body for its building up; its mutual edification.

Do I do my job best locked away in an office with the Bible and some commentaries open, typing into a word processor for 30 hours a week, or do I do my best listening to the wisdom of the body talking to others, with the Bible open, and thinking through how the passage best speaks to the diversity of people in the body, and to the world in a way that makes what is being said plausible and engaged, rather than detached and idiosyncratic. Let’s take Paul’s metaphor of the body seriously; and metaphorically — a metaphor is not an exaggeration of the true state of affairs, but an accessible simplification — a sign that points to a greater reality — a ‘simplification’ you use to make something more complex understandable… so when Paul speaks of the church as a body we’re not meant to think he’s over-applying the reality of our union (with Christ, by the Spirit), but pointing to a deeper mystery. And we might, to use Paul’s metaphor, understand preaching — as in the spoken word in the gathering — as the act of the body’s mouth; when my mouth speaks it is connected to my brain, powered by my lungs, informed by my eyes and ears… and representative of the rest of me (and my actions) if my words have integrity.

“If the whole body were an eye, where would the sense of hearing be? If the whole body were an ear, where would the sense of smell be? But in fact God has placed the parts in the body, every one of them, just as he wanted them to be. If they were all one part, where would the body be? As it is, there are many parts, but one body.…there should be no division in the body, but that its parts should have equal concern for each other.” — 1 Corinthians 12:17-20, 25

The Locution: if we’re going to speak the word of God, what do we say?

4. These human messengers do not invent their own message, but receive it from God’s revelation; these human messengers faithfully proclaim this received message by preaching the message without modification.

5. In a general sense, any message received from God would be the word of God. But, in a special sense, as a result of God’s progressive revelation, an important content of the word of God is the Christocentric gospel. In this special sense, the word of God is now not only the word from God, it is the word about God, namely, his Son. This message is continuous with the message of the OT prophets, which was subsequently inscripturated as OT Scripture, but it is also a climactic new message that has only now been revealed through the preaching of Jesus and the apostles, which has now been inscripturated as NT Scripture.

One way of thinking of the locution is that it’s the message; it’s what is transmitted from speaker to audience. But the thing that separates ‘locution’ from other forms of communication is that it is part of a speech-act — it is spoken not just transmitted, or read. The message in this sense starts to include the ‘medium’ which is part locution, part illocution (the next bit); and here’s where some of my thesis intersects with Sam’s work; because in some sense the act of preaching is where the communication maxim “the medium is the message” kicks in a bit (which is from media ecologist Marshall McLuhan); the way this plays out in preaching is that somehow what we locute — the Gospel — is connected to who we are (appointed speakers of the Gospel; God’s ambassadors/image bearers), and in some way the act of speaking, as a dynamic and relational act is a ‘medium’ choice that reinforces the nature of the message (and that it comes from the God who speaks). This also helps speech-act theory integrate with classical ‘oratorical’ theory — where each ‘speech act’ incorporates elements of logos, ethos, and pathos — the locution is in a sense the overlap between ethos, logos and the action of speaking (I’d argue pathos is more caught up in the illocution but not totally removed from locution because we speak words that move our emotions too, not just speak emotionally).

There’s a reason God’s message is best spoken, not just read, that preaching is a thing and we don’t just hand out Bibles. It’s because God is a dynamic and relational God, and somehow our locution and our illocution is an opportunity to model that. Here’s more from the book, and they’re important, because it’s at the heart of Sam’s thesis that preaching is speaking the words of God, that we understand what the ‘word of God’ looks like.

In one sense, Christ is the Word because he is the Word from God; he is the climactic revelation from God. As the Son sent by God, he speaks the Father’s message on the Father’s behalf; as God incarnate, his words are also God’s words. But in another sense, Christ is the Word because he himself is the message. The message from God is about Christ; the referent of the word is Christ himself—his person, work, and message. He is the fulfillment of the Old Testament message of eschatological salvation; he is the Messiah who will usher in the kingdom of God and bring salvation and vindication for God’s faithful people.

Therefore, today, God reveals his message of the gospel to his commissioned, Spirit-anointed preachers through the reading of the word and the proclamation of the word. This word is a Christocentric word, namely, the gospel that calls all to recognize Jesus as the Christ and to live a life of trust and obedience in Christ. In turn, the Christian preacher is to proclaim this Christocentric gospel message, and in doing so, preach the word of God. This message should be consistent with the message of the gospel in Scripture; and the hearers can confirm this by examining the Scriptures.

The question to determine whether or not God’s word is being spoken at this point in a speech-act, according to Sam’s thesis is:

“Does the preacher’s locution correspond with that of the gospel message of Scripture?”

The Illocution: If we’re speaking the word of God how do we say it?

“the illocutionary act is the performance of an act in saying something. It corresponds to the force of what has been said.”

In terms of speech-act theory the illocution is what makes the speech an action (so a ‘promise’ (‘I do‘) not just the words used in a promise (‘I do’) — it’s the difference between me reading aloud the words of an oath on a page and making an oath).

It might be helpful to think of the locution as a ‘ball’ and the ‘illocution’ as the throw. If the locution is the content of a speech act, the illocution is the act itself; the manner in which it is delivered consistent with its purpose and function. So if the ball is a cricket ball the ‘throw’ might, depending on context come from a bowler, a fielder, or a member of the crowd; each ‘ball’ is the same, but the meaning is different because of the context and understanding of the action (one is bowling, one is fielding, one is fetching).

In a speech-act, the locution is what is said; the illocution is how it is said (and what makes the ‘locution’ something more than ‘just words’). It’s partly context that determines this; including our expectations of the locutor (so, neither a fielder or a spectator ‘bowl’… but a fielder ‘becomes a bowler’ when they give their hat to the umpire and take their mark). It’s ultimately context that enacts the speaking of certain words to make them a ‘speech-act’; the words ‘I do’ become a vow in a wedding, rather than simply an expression of my opinion, or description of my actions (“do you eat chocolate?” “I do” is very different to the act of saying “I do” in a wedding ceremony but the same words). This context also includes things other than who the speaker is, who they’re speaking to (and the recognised conventions this creates), it also includes intent. So, to pick up the cricket analogy again; we know a ball is bowled in cricket when the bowler bowls to the batsman, and there are rules around what is recognised as a legitimate bowling action (behind the crease, between the popping creases, below the shoulders of the batsman), there’s also a certain force required and the intent to get the ball into play, but there’s still, in terms of how we assess the bowling, a required interaction with the batsman (this is where the next bit, perlocution, comes in). An over in cricket is not just six balls, but six balls bowled from bowler to batsman. A speech act is not just words, but words spoken in a particular context with a particular force.

It’s useful to think about illocution as the thing that makes you feel the weight of the locution so that it is an action (a bit like how ethos and pathos intersect in the old rhetorical triangle). And one act of speaking might have multiple illocutions; multiple purposes, and this depends on the contexts. A ball bowled in cricket is bowled to terrorise a batsman, to be hit by a batsman, to get a batsman out, to excite the crowd, to encourage the field, and to please the captain; the same ‘ball’ bowled can do all these things. And it’s the same with a speech-act; there can be multiple illocutions at play. And Sam argues this is true in preaching. It’s not our job simply to say ‘ball… ball… ball’… we actually want the ball to do something. Here’s Sam’s next point:

6. The human preacher preaches with a divinely commissioned intention, which is an expression of God’s purposes, on behalf of God; and God achieves his purposes through this human proclamation.

This is where we move from content to method; and though experience listening to some sermons that don’t nail the ‘gospel message of Scripture’ might suggest otherwise, there’s nothing particularly controversial in Sam’s thesis until this point. But this is where things get interesting. There are some popular approaches to preaching that see our job simply as describing the word of God propositionally; our job is to simply show what God’s locution is; one way this happens is in a certain sort of expository preaching. Sam suggests this evangelical sacred cow is not all it is cracked up to be; that it may, in fact, be undermining what preaching should be. He’s quite charitable about the theory behind expository preaching, but asks a legitimate question about whether it might actually be imposing a pretty modern construct on a text that had a purpose apart from the delivery of authoritative propositions. He suggests it’s possible that our approach of turning the Bible into propositions (bits of data), or put another way, treating it as a ‘locution’ not a dynamic speech-act where illocution matters too, might rob it (and our preaching) of its speech-act nature (a way of thinking about this might be to say that when we do this the Bible, God’s ‘living and active word’ simply says something, but if the speech-act thing is captured in our reading and preaching, the Bible does something again, and the challenge of our preaching is that our spoken words don’t just say something, but also do something).

“The merits of this approach are that it is founded upon a high view of Scripture—for Scripture is the word of God—and it emphasises the need for objective controls in preaching, namely, Scripture itself. However, this approach is not without problems… often, this approach is somewhat dependent upon a “propositional” view of revelation, for the preacher is essentially gleaning ideas, concepts, principles, and propositions from the scriptural text. But this reliance upon a “propositional” view of revelation would share some of the weaknesses of such a reductionist approach. Further, much of the literary genres of the Bible are not easily reduced to propositions or principles. Is such preaching, then, committing the so-called “heresy of propositional paraphrase”?

Sam says expository preaching reduces the speech act to locution, so the word of God in the sermon is basically the bits where the Scripture is quoted, paraphrased, and explained, and “there is little attempt to recapture the illocutionary act of Scripture.” So sometimes, for example, when we preach a passage of narrative with the ‘three points and an application’ model, and we do this by picking out details and ‘facts’ rather than by telling the story, we rob the passage of its function (and thus, it’s meaning and purpose). He suggests, using speech-act theory and this concept of illocution, that we should not just be transmitting the locutionary content of Scripture, but that we should be seeking to preach in such a way that the purpose of a particular piece of scripture is achieved in our speaking; our illocution when we teach a passage should line up with its illocution (especially in the context of the whole Bible, so as it helps bring the Gospel to people in different contexts to produce different actions (promise, threat, etc) and these actions are shaped by the text. There’s a responsibility here not just for the ‘mouth’ of the body; the preacher; to speaking well, but for the rest of the body (and other hearers open to the premise that God might be speaking) to be playing a role “to check that the locution of the proclamation is indeed identical to that of Scripture.” Expository preaching makes this a bit easier because all the audience has to do is make sure the preacher is saying what the text says, not also doing what the text does, but the challenge of Sam’s thesis (which draws on the methods of preachers in the Bible, not just their content), is to aim not just to ‘teach’ the locution (the Gospel) but to bring it to bear. We don’t just hold up the cricket ball so all might see it’s a ball, we bowl it with the force required to achieve a purpose; God’s purpose, and just as a ball well-bowled achieves a variety of purposes depending on who you are relative to the ball (batsman, bowler, fielder or spectator), the preached word does this too, as Sam puts it:

And not only that, it must recognize that there is a variety of illocutionary acts that accompanies the single locutionary act of the gospel. In the proclamation of the apostles, the gospel message (“we preach Christ crucified”) is accompanied by a variety of illocutionary forces. For example, it is a promise to those who believe, an urge to repentance to those who don’t believe, a blessing to the faithful, a curse to the unfaithful, an encouragement to those who suffer, a warning to those about to fall away, a command to persevere, an assertion of a historical fact, an explanation to those who ask, an apology against the attackers of Christianity, and so on… there is a variety of illocutionary forces at the level of a single passage of Scripture, the level of a single book and its genre, and at the level of the entire canon. Thus, it also follows that there is a variety of illocutionary forces that accompanies the single locutionary act of the preached gospel. And a holistic understanding of preaching will appreciate this. In other words, it is important to maintain the distinction between the locutionary and the illocutionary act; for although there is only one locutionary message, there can be multiple illocutionary acts that accompany it. Thus, an approach that emphasizes one particular illocutionary act, such as “teaching” or “explanation,” and equates this with “true preaching,” has unfortunately confused the distinction between the locutionary and illocutionary act, and has become reductionistic in its use of illocutionary forces.

…when the gospel was preached by Jesus and the apostles, it was accompanied by a variety of illocutionary forces—promise, exhortation, encouragement, command, warning, blessing, assertion, explanation, judgment, etc. Thus, here, the preacher has a choice of a variety of illocutionary forces with which to preach the gospel; the preacher is not restricted to only one particular illocutionary force. In the same way that Jesus and the apostles used different illocutionary forces for different audiences and contexts, the contemporary preacher might also choose to use different illocutionary forces. Therefore, we cannot say that there is only one illocutionary force that is necessary for the preached gospel to be the word of God; there exists a variety of illocutionary forces that may accompany the preached gospel as the word of God.

So Sam’s question about whether a bit of preaching is a speech-act where God is speaking is: “Does the preacher’s illocution correspond with that of the gospel message of Scripture?” What is the illocutionary force?”

And it’s useful to think, briefly, about how we go about doing this, how we illocute, not simply locute. How we preach the purpose of the passage not just display the passage. How we approach narrative as narrative, not simply as a text to turn into propositions (Sam follows Kevin Van Hoozer in suggesting that both genre, and the passage’s place in the ‘canonical’ context of God’s grand ‘gospel centred’ acting in the world is really important for understanding the illocutionary force of a passage). We don’t just read Old Testament law as commands for us, but as part of the canon that shows how these laws help us understand the story of Jesus, so the illocutionary force isn’t in making people feel the weight of obedience to a command from the Old Testament, but in understanding the function of these commands.

But part of capturing and expressing the force of God’s word might also include things we might describe as media, or delivery decisions (just as a bowler at the top of his run considers pace, and line, and length, and swing, and seam position): do I shout, or whisper? What tone or expression or emphasis do I use? What body language do I employ? How do I distinguish in manner between, for example, a threat and a promise? How do I shape the delivery of the message in order for it to be heard according to its purpose (this leads into the next bit, the perlocution)? It also includes questions of audience like ‘what is my relationship to these people? How will they understand the nature of these words?

I know a promise is a promise not a threat, even if the same words are used, because somehow I’m geared to feel the difference not just by the words used, but how they’re used (and who is using them).

The perlocution?

The perlocutionary act is the performance of an act by saying something. It corresponds to the effect of what has been said.

The question at this point is: how much responsibility should the preacher take for the response to the preached word?

Can we talk as though we are responsible for the response to the preached word, or as though the response to the preached word should be part of how we measure the efficacy of preaching? Should we, for example, determine how good a preacher is by how persuasive they are? By how many people are persuaded? Or be aiming at persuasion at all?

And if the answer to the first question is ‘none’, then how much should persuasion be a factor in our preaching (how much should we think about the result for the hearer, not simply the act of speaking (locution and illocution).

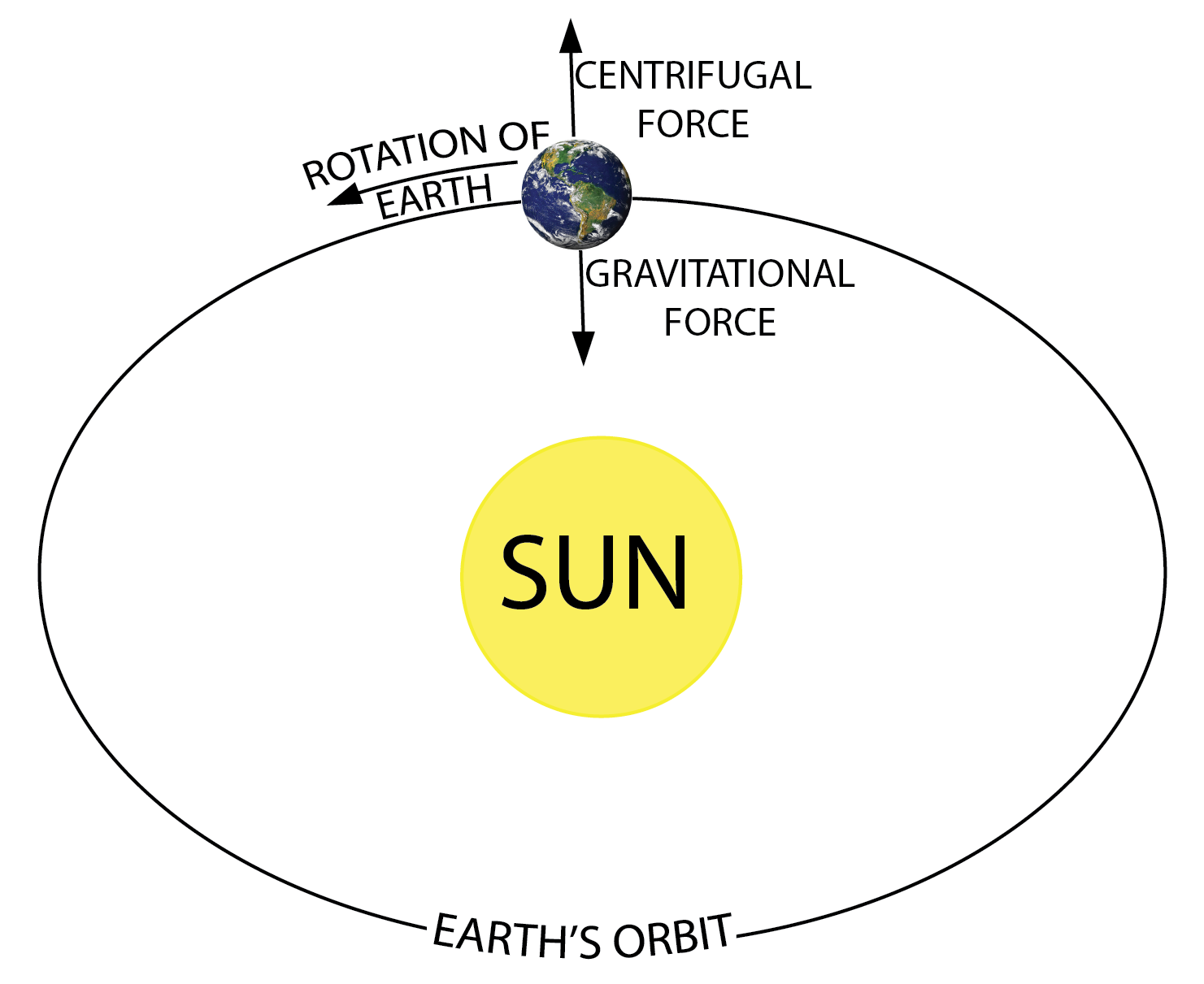

For Sam, because of a theology I share, which sees God responsible for the effect of the preached word (and the effect produced by the Spirit), the answer to the first question is that God is ultimately responsible, and the speech-act is complete, so far as the speaker is concerned, with illocution, rather than the effect. The perlocution is the responsibility of the Spirit working in the hearer. Here’s Sam’s point 7:

7. Nonetheless, because of God’s “hidden” intention, and because of the different roles of the preacher, the hearer, and the Spirit, the ultimate result of preaching among the hearers is not a criterion for determining if the word of God is preached. Thus, the status of the preached word as the word of God is independent of its results. It is precisely because the preached word is God’s word that the preacher is not responsible for the hearer’s response and the hearer is accountable to God for his or her own response.

And a couple more quotes to flesh out the summary of his position above:

“The aim of preaching, as I have argued, is to perform a speech act on behalf of God… in order to perform a speech act on behalf of God, the preacher’s locution and illocution are to correspond with God’s locution and illocution.”

“The distinction between the illocutionary act and the perlocutionary act is crucial. The preacher is responsible for the illocutionary act, which in turn is dependent upon the locutionary act. But the preacher is not responsible for the perlocutionary act. Instead, it is the Holy Spirit and the hearer who have the dual responsibility for the perlocutionary act, that is, belief and obedience.”

He draws on Paul’s words regarding his own approach to preaching (and ministry) to conclude:

“The proclaimer cannot coerce, manipulate, or force a hearer to believe or obey. That is, although the proclaimer must ensure that the gospel is illocuted, the speaker cannot ensure that the hearer responds with faith and repentance. The hearer is responsible for his or her response, not the proclaimer. Thus, a proclaimer is to illocute “Christ crucified” (1 Cor 1:23) without resorting to “wise and persuasive words” (1 Cor 2:4), that is, to coerce or manipulate. For that would be to confuse the illocutionary with the perlocutionary act.”

Now it would be possible to take this point of Sam’s on board and therefore not see preaching in terms of its fruit at all; or even to not aim to persuade as the human vessel of God’s speech. And exactly how this works out in the wash is one area where we hit the limits of Sam’s book (it can’t do everything), but also where my thesis picks up; I wrote mostly trying to figure out how we should be God’s communicating people in the world — how we might bear his image and so glorify him — and then approach worldly methods of communication like rhetoric, oratory, and public relations; how we might ethically engage in persuasion using some of these tools; rather than engaging in manipulation; how we might recognise the theological limits of our involvement in producing a result, not have our faithfulness measured by results, and yet still seek a result, and see results as a good thing to humanly pursue, and even to celebrate.

Here’s some stuff from my thesis:

“Most communicative acts, as actions of the sender, are produced for a purpose; this purpose may simply be to transmit the information, but usually the purpose is to produce a “perlocutionary effect” – such communication aims to bring sender and receiver to a common understanding of the information, and apply its implications. At this point communication becomes an exercise in persuasion, and while the sender cannot dictate the recipient’s response, they can “strategically” consider the desired perlocutionary effect in the communicative act. This consideration will affect the choice of content, genre, and form within certain “rules of the game,” supplying a context such that both sender and receiver are aware of the implications of the act.”

I go on to argue in this thesis that speech-acts that are open about their intent to persuade; and the ‘perlocution’ they intend to achieve are not manipulative, and are actually more ethical than communication because, in acknowledging the intent up front (or through genre/convention — and I think a ‘sermon’ carries with it a particular contextual expectation where the listener, Christian or otherwise, expects to be persuaded to act according to the word and authority of God mediated through the preaching). The key control here is that the what (the locution: in this case the Gospel) is thoroughly embedded in its connection to the who is speaking (the locutor: in this case, as above, the preacher/church/God); and for it to be ethical (for the ‘ethos’ component to work; the perlocutionary affect needs to reflect the life, or desired life, of the speaker, not just the audience).

Paul also says:

“Rather, we have renounced secret and shameful ways; we do not use deception, nor do we distort the word of God. On the contrary, by setting forth the truth plainly we commend ourselves to everyone’s conscience in the sight of God.” — 2 Corinthians 4:2

And this has often been used to suggest that Paul swore off persuasion the way it was practiced by first century orators; I’d counter that this is actually a rhetorical practice/strategy and ‘commending himself’ is actually a perlocutionary effect produced by his strategy (the sort of effect he relies on elsewhere when he says ‘imitate me as I imitate Christ’). But. We’ve got to hold this alongside Paul’s statements about his own perlocutionary goals in his ministry (which includes his preaching); and it’s worth noting that his goals are to produce people just like him in their shared being just like Jesus — people who imitate him as they imitate Christ; but also people who by the Spirit are brought into the body of Christ-in-the-world — the church… the messengers who are commissioned to live and carry this message.

Like Sam, Paul suggests the heart of God’s locution (or his message as one speaking God’s word to the world (as Christ’s ambassadors (2 Cor 5:20), is the Gospel. His illocution is shaped by the Gospel too, inasmuch as it includes not just shaping his illocutionary speech-acts with the Gospel (renouncing ‘powerful’ and ‘underhanded techniques), but also shaping his ‘act-speeches’ — his ethos — around the Gospel. Here’s how the Gospel shapes Paul’s locution, illocution, and understanding of perlocution in his preaching speech-acts from 2 Corinthians 4… and this does support Sam’s conclusions about who produces the perlocutionary affect:

“The god of this age has blinded the minds of unbelievers, so that they cannot see the light of the gospel that displays the glory of Christ, who is the image of God. For what we preach is not ourselves, but Jesus Christ as Lord, and ourselves as your servants for Jesus’ sake.For God, who said, “Let light shine out of darkness,” made his light shine in our hearts to give us the light of the knowledge of God’s glory displayed in the face of Christ…

We always carry around in our body the death of Jesus, so that the life of Jesus may also be revealed in our body. For we who are alive are always being given over to death for Jesus’ sake, so that his life may also be revealed in our mortal body. So then, death is at work in us, but life is at work in you.

It is written: “I believed; therefore I have spoken.” Since we have that same spirit of faith, we also believe and therefore speak, because we know that the one who raised the Lord Jesus from the dead will also raise us with Jesus and present us with you to himself. — 2 Corinthians 3:4-6, 10-14

But this belief that it is God who will raise us from the dead by his word, and bring ‘light to our hearts’ so we might know the power of the Gospel truly; free from blindness, does not stop Paul believing that somehow he is involved in securing a perlocutionary affect, and so aiming his communication to that end.

In 1 Corinthians 9 Paul spells out why he preaches the Gospel the way he does in Corinth (despite their preferences for flashy persuasive speech from people they pay to influence (orators). And having spelled out why he does not take up certain rights as a preacher, he says:

“ Though I am free and belong to no one, I have made myself a slave to everyone, to win as many as possible. To the Jews I became like a Jew, to win the Jews.To those under the law I became like one under the law (though I myself am not under the law), so as to win those under the law. To those not having the law I became like one not having the law (though I am not free from God’s law but am under Christ’s law), so as to win those not having the law. To the weak I became weak, to win the weak. I have become all things to all people so that by all possible means I might save some. I do all this for the sake of the gospel, that I may share in its blessings.” — 1 Corinthians 9:19-23

This becoming is to produce a perlocutionary affect — it’s to win as many as possible. It’s also a reflection of the Gospel (parallel this with Philippians 2 and Jesus ‘making himself nothing’). How he understands himself (and the church) as ‘locutors,’ his methodology, his message, the force he gives it (in 1 Cor 1-4, and 2 Cor 3-5) and his intended results, and how that shapes the other elements so that they are in harmony. We see Paul shift methods and emphasis in his locution (and illocution) throughout Acts based on who he is speaking to (so compare his preaching in Athens, before the Pharisees and Sadducees, and before Felix or Festus), though the perlocution he aims for, under God, in this shifting strategy and method seems consistent, that people might know Jesus as Lord. And this is, I think, part of why he sees himself speaking the word of God (and it’s why Sam’s book is a good one for us to grapple with).

To pick up the cricket analogy, this means that while we expect good bowling to produce wickets, and we value wickets, and bowl with the intention of taking wickets, we measure the bowling on the effort of the bowler, on the quality and consistency of the balls delivered, their integrity within the team context and that they bowl in such a way that wickets are a reasonable expectation based on past experience and a reading of the present conditions. It’s not wickets being taken that determines if a bowler is bowling for Australia, but that they are selected to represent our nation and are doing what they are appointed to as part of the team (and on our behalf).

This is a great book on preaching not just because it is carefully thought through and argued, and not simply because it brings some fruitful modern insights into language and communication to give us a sense of what is happening as we preach, but because it reminds us as hearers and speakers of God’s word that preaching is powerful, and more than this, that God is a God who speaks and life happens.

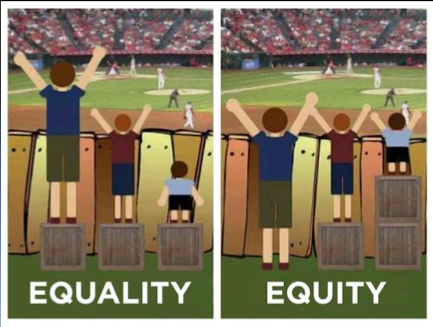

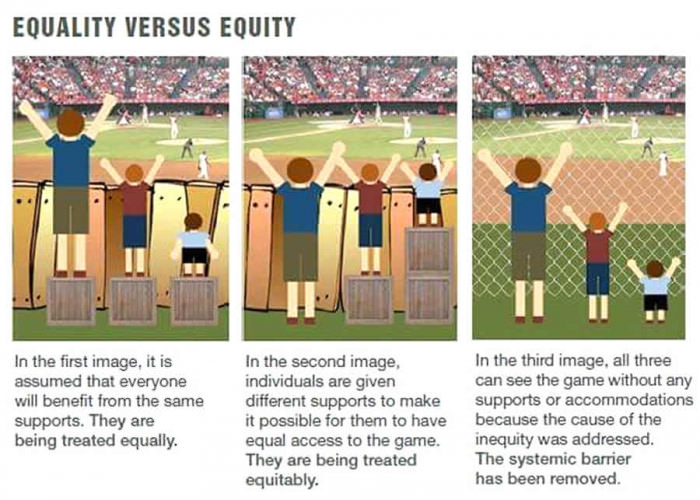

Egalitarianism — the equality of men and women — is the world’s naive, or optimistic, solution to the problem of cursed life in the world; it’s a solution that comes without truly understanding that the problem is that life in the world is cursed, and that we can’t fix the curse ourselves just by pretending it isn’t there. It recognises a truth about our equality in dignity and value, and is less likely to accept the parameters offered to us by curse and sin. But it often settles for equality or equity as solutions, and doesn’t totally acknowledge that our difference is real, and that sin and curse have exaggerated the impact of that difference. It is an attempt to respond to a broken world by creating a new one (and in some sense, it does look forward to the new creation, but perhaps optimistically over-realises that picture in this world). So for Christians to adopt it just strikes me as missing the heart of the diagnosis, and the solution, that come with our story. As

Egalitarianism — the equality of men and women — is the world’s naive, or optimistic, solution to the problem of cursed life in the world; it’s a solution that comes without truly understanding that the problem is that life in the world is cursed, and that we can’t fix the curse ourselves just by pretending it isn’t there. It recognises a truth about our equality in dignity and value, and is less likely to accept the parameters offered to us by curse and sin. But it often settles for equality or equity as solutions, and doesn’t totally acknowledge that our difference is real, and that sin and curse have exaggerated the impact of that difference. It is an attempt to respond to a broken world by creating a new one (and in some sense, it does look forward to the new creation, but perhaps optimistically over-realises that picture in this world). So for Christians to adopt it just strikes me as missing the heart of the diagnosis, and the solution, that come with our story. As