Did you hear the one about the government that didn’t build religious freedom legislation into its amendment to the Marriage Act?

I did. I can’t stop hearing about it.

If you follow the Christian blogosphere in Australia you’ll be seeing plenty of posts following the parliamentary debate in the senate overnight; a debate passing the changes to the Marriage Act that the Aussie people called for via the clunky mechanism of the postal survey. The conservative Liberal/National Coalition passing this legislation, rather than a progressive Labor/Greens alliance was a great silver lining for Christians who believe in traditional marriage; these guys, ‘our people,’ understand that religious freedoms are important…

Only…

There’s a problem. The government didn’t bring in religious freedom protections, via amendments, in the bill it put forward as a result of the postal survey.

Two problems.

One is that the government has always said it will deal with religious freedoms separate to the actual act so these rejected amendments were all political grandstanding from a section of the Coalition who are trying to undermine Turnbull’s leadership; and all these bloggers are adding fuel to that fire. We’re pawns in someone else’s political game, when, as I’ll argue, we should be playing our own.

There’s also a problem with how our government and our nation understand the phrase religious freedom.

Bizarrely the conversation around religious freedoms has largely been about the freedom of Christians to define terms for ourselves (and for other theists from classic organised religions), rather than it being a two way street figuring out how different communities built on different ideals can live together in a pluralist context. This has just come across as us wanting to protect our privilege to hate and discriminate; which isn’t what I necessarily want brand Christian to stand for. It’ll continue to do this the more we bang the ‘victim’ drum in this debate; especially when the Aussie populace (perhaps rightly in some of these cases) believe we’ve voted to end a form of systemic inequality or oppression; to strike a blow against the persecution of minority groups; and to confer full human rights (and thus human dignity) on a community within our nation.

More bizarrely the conversation around religious freedom has been around the freedom not to participate in free common space (like public education, and especially sex ed classes), and to protect Christians wanting to operate businesses catering to the public around the wedding industry (florists and bakers). I feel like we want to have our cake and eat it too on this front; Christians decried corporate Australia jumping on board the same sex marriage bandwagon and essentially discriminating against Christians in their hiring practices, which surely is an expression of the religious freedom of a society that worships sex to hire and participate in public life accordingly, though it costs us Christians; but at the same time want Christian business people to be able to act according to religious beliefs without it costing them. It seems we just want the laws of the land to revolve around what is good for us; not what works for all of us. If we want bakers to be free to sell cakes to whoever they want, and schools to be able to hire Christian janitors, then it seems to me we should be happy to allow Qantas to bring in special marriage equality rings, and tennis organisations to rename their arenas…

Perhaps most bizarrely though, the conversation around religious freedom has been around the rights of church celebrants to not marry people (a right we already have under the Marriage Act, where we can refuse to marry anybody we want, without reason, but also only marry according to the religious rites of our institution (it is the institution that is recognised, not us as individuals). What’s bizarre about this is that it is a thin view of the nature of religious belief; and one for which we, the church in the western world, must shoulder the blame.

We’ve got a thinned out vision of religious life; we ourselves operate as though there’s the sacred space of church on a Sunday; as though church’s are an embassy of heaven, and the secular space of the rest of the world; as though our sacred lives are caught up in religious pomp and ceremony, but our secular lives, our public lives, are not remarkably different from those around us; as though faith is a private (sub-)intellectual conviction that we shouldn’t bother anybody with, while our public lives are lived according to the shared values of reason and the pursuit of common ground. We’ve denied and played down the difference between Christian living and the lives of our neighbours, and now when we want to maintain some sort of distinction we’re creating the impression that this — same sex marriage — is the only point at which it matters for us to be different; as though this is where our nation is departing from God’s design.

This is our fault.

Our political lobbyists have talked up a Christian constituency for years based on census data, all the while knowing that active engagement in church life — a faith with flesh and bones — makes Christianity a significant minority in our country (with disproportionate influence in our civic institutions — like our politicians still praying the Lord’s Prayer). We’ve done this while talking down anything that looks like religious reasoning for our positions; preferring to make arguments from ‘nature’ or ‘logic’ as opposed to saying “we believe God says X, and that belief shapes our community”… we’ve overreached as a result, denying that other religious communities (or non religious communities) do not share our convictions about nature, or the character of God. At a conference I went to a couple of years ago an Aussie law professor, Joel Harrison, made the point that our judicial system cannot and does not accept religious arguments as legitimate motivation for behaviour because of the way our legal system operates and understands behaviours and motivations for behaviours; the spiritual is closed out, so it doesn’t get a look in.

Our (evangelical) churches have settled for a ‘faith alone’ approach to Christianity that emphasises a personal rational assent to particular truths about God and the Gospel as what ‘counts’ for Christians; a ‘tick a box’ Christianity (that matches our census approach) so that making disciples has largely been about winning arguments, not so much about forming people who imitate Jesus in rich communities that live lives of thick difference from the community around us; not just when it comes to sexual ethics. We see conversion as being pretty much exclusively about the head, which when our culture sees religion as, in the words of Manning Clark, ‘a shy hope in the heart’ — a private thing that doesn’t really motivate how we live outside our homes — means we avoid anything particularly radical.

The connection between what we believe and talk about on Sundays and how we live apart from Sundays such that religious freedom is about anything other than Sundays is not obvious to most Christians, let alone our secular politicians.

And our culture perpetuates this myth every time political correctness kicks in such that the behaviour of religious radicals is explained away as simply political; because we’ve decided the sacred is only what happens in the institutional practice and teaching of religious belief; not in the lives of believers as motivated by belief.

This is our fault… and the way to change it is to totally reverse our strategy.

To pursue thick community that is different to the world around us in that it reclaims every inch of life for a believer as sacred; such that it is unimaginable for us to participate in the public or political life of our country without doing so as people who first bend the knee and submit our lives (in every sphere, for example economically not just sexually) to Jesus.

We need to have an approach to education and formation that isn’t just about the head and what is taught, but about allegiance and practices (who we serve and what we do). We need to recapture a grand organising narrative for our lives so that our ethics are connected to something we can easily communicate and explain to people who don’t share it; rather than seeing faith as being a private, disconnected, part of who we are. We have to be able to understand our own behaviour, and account for it, in a way that is connected to this story and such that our behaviour is different to the behaviour of others — and we need to be prepared to simultaneously cop the sort of opposition that difference brings, and give the sort of generous space to others that we want to be afforded ourselves. So, for example, give away our wedding cakes and flowers to gay couples (especially if we suspect a court case is part of the intent) if we don’t want to profit from things we disagree with, as a sign of rich disagreement and love… and hire non-Christian janitors, and (continue to) accept non-Christian kids for our Christian schools as an act of inclusion — but make it clear why we are only hiring Christian teachers and how our approach to education is connected to our understanding of the good life — the Gospel — not just to getting a good education for our kids so they might prosper (the false Gospel). As an aside, every person on staff at a Christian or church run school should have to read Augustine’s On Christian Teaching.

We also need to be prepared to practice a particular sort of faithful presence in our community to model difference that isn’t disinterested or withdrawing difference; not withdraw our kids from classes that teach people stuff we disagree with (especially if we ever tell our kids to invite their friends along to hear about Jesus).

The sky isn’t falling in; it’s the same is it was yesterday. It’s the ‘sky’ Charles Taylor describes in A Secular Age. He even describes the path to getting there; and as you skim this, just imagine how our Christian political strategy (think about the no campaign for an example) reinforces this way of seeing the world.

He starts by talking about our current political reality.

“The political organisation of all pre-modern societies was in some way connected to, based on, guaranteed by some faith in, or adherence to God, or some notion of ultimate reality, the modern Western state is free from this connection. Churches are now separate from political structures. Put in another way, in our “secular” societies, you can engage fully in politics without ever encountering God.”

Just imagine if we, churches, adopted a strategy that reinforced this status quo. Oh wait. We have.

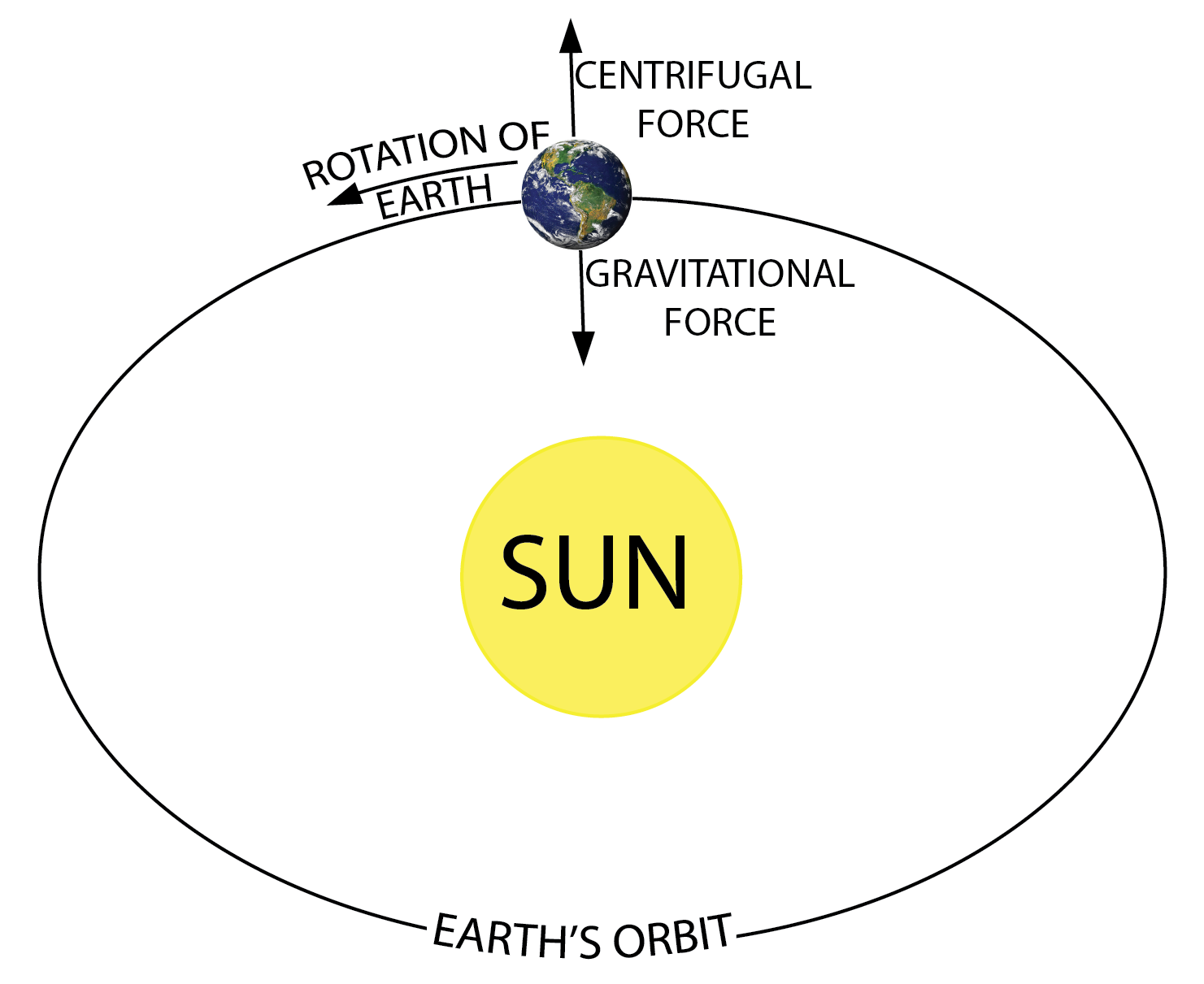

But what this means, this shift, is that people in our world don’t have a real understanding of anything sacred, just this secular vision of reality where God has no place. Taylor calls this the ‘immanent frame’. Here’s the progression from the pre-modern to the modern western view.

At first, the social order is seen as offering us a blueprint for how things, in the human realm, can hang together to our mutual benefit, and this is identified with the plan of Providence, what God asks us to realize. But it is in the nature of a self-sufficient immanent order that it can be envisaged without reference to God; and very soon the proper blueprint is attributed to Nature. This change can, of course, involve nothing of importance, if we go on seeing God as the Author of Nature, just a notational variant on the first view. But following a path opened by Spinoza, we can also see Nature as identical with God, and then as independent from God. The Plan is without a planner. A further step can then be taken, where we see the Plan as what we come to share and adhere to in the process of civilization and Enlightenment; either because we are capable of rising to a universal view, to the outlook, for instance, of the “impartial spectator”; or because our innate sympathy extends to all human beings; or because our attachment to rational freedom in the end shows us how we ought to behave.”

Our modern world operates as though God is not in the picture; and if Christians are right that’s a terrible and deadly mistake. The problem is that we’ve helped. We Christians have adopted a strategy of political engagement that is formed in this secular millieu, by its assumptions about politics… the idea that lawmakers don’t need to understand religious belief to make laws, just ‘nature’… and then when we lose the ‘nature’ argument we’ve mounted we want to turn around and ask for religious exemptions?

Seriously.

This also means that our modern world is ill-equipped to understand why a symbolic cake matters to a baker, or why exemptions for clergy don’t really cut it.

We also have a politics to fix this.

We have our own political game that makes sure we see the secular consumed by the sacred when we bend our knee to King Jesus. Church isn’t an embassy; we don’t stand on sacred ground on Sundays. We are ambassadors. We are sacred, priestly, people wherever we go. This was part of the heart of the revolution of the Reformation; the same movement that brought us faith alone (and probably democracy) brought us the priesthood of all believers; the idea that everything we do in this world is a sacred act of priestly service to God. Luther wrote a letter to the Christian nobility — a political letter, to politicians — his purpose was to take the power to decide what was sacred and profane away from the corrupt institutional (and political) church, and put it in the hands of everybody (including the politicians of his day). The church was claiming that it had power over the state because the church was ‘sacred’ or spiritual while the state was ‘secular’ or temporal… Luther said:

“It is pure invention that pope, bishops, priests and monks are to be called the “spiritual estate”; princes, lords, artisans, and farmers the “temporal estate.” That is indeed a fine bit of lying and hypocrisy. Yet no one should be frightened by it; and for this reason — viz., that all Christians are truly of the “spiritual estate,” and there is among them no difference at all but that of office, as Paul says in I Corinthians 12:12, We are all one body, yet every member has its own work, where by it serves every other, all because we have one baptism, one Gospel, one faith, and are all alike Christians; for baptism, Gospel and faith alone make us “spiritual” and a Christian people.”

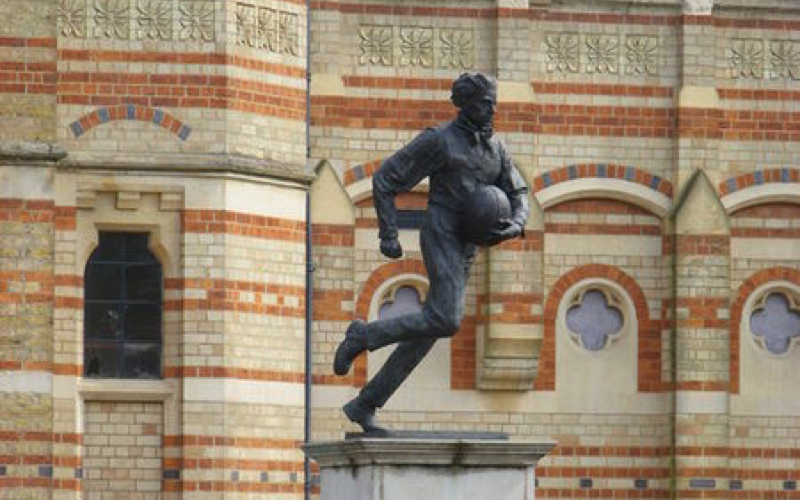

Farmers and people who make stuff… politicians… teachers… butchers, bakers, florists… if you’re a Christian you belong to the ‘spiritual estate’, your work is sacred. Our government doesn’t understand that, because for the most part, neither do we. Protections for clergy aren’t enough; especially not for protestant Christians who agree with Luther. Luther also said:

“There is really no difference between laymen and priests, princes and bishops, “spirituals” and “temporals,” as they call them, except that of office and work… just as Those who are now called “spiritual” — priests, bishops or popes — are neither different from other Christians nor superior to them, except that they are charged with the administration of the Word of God and the sacraments, which is their work and office, so it is with the temporal authorities, — they bear sword and rod with which to punish the evil and to protect die good. A cobbler, a smith, a farmer, each has the work and office of his trade, and yet they are all alike consecrated priests and bishops, and every one by means of his own work or office must benefit and serve every other, that in this way many kinds of work may be done for the bodily and spiritual welfare of the community, even as all the members of the body serve one another.”

Every occupation held by a Christian is sacred so long as their work is for the bodily and spiritual (you can’t disconnect those in his though) welfare of the community. That the government doesn’t understand that we think this is our fault, because where else do they gain an understanding about the lives and beliefs of Christians apart from how we live, and what we say to our politicians? Or, what we allow to be said on our behalf by our lobby groups?

We have a very clear political mandate, especially in a world that lives life without God and believes that to be ‘good’… We have a mission to follow the one who broke through the ‘brass dome’ of the natural world as a super-natural emissary from the God of heaven; though he wasn’t just the ambassador; he was the visiting king of what he calls the Kingdom of Heaven. Our secular politics has been the result of allowing the church to box this king into a corner; a corner where he has almost no apparent relevance to the day to day life of Aussie believers so far as those looking on can tell (except when it comes to how we think about sex).

The Gospel is, itself, political. It is the proclamation that Jesus is king; that God is the creator and through Jesus claims every inch of our lives and of the world; that he died, was raised, rules, and will return to renew the world for his resurrected people living as his kingdom. This proclamation has profound implications for how people who believe it live now; in other kingdoms, and how we live with one another as this kingdom.

Church properties aren’t sacred embassies, or sanctuaries (though they’ve been recognised that way in the past), clergy aren’t particularly extra-specially sacred or priestly… church communities are sacred ambassadors for this king.

This is our politics. And we’ve forgotten it. We’ve played the ‘secular game’ for too long… and it has come at a cost.

Since, then, we know what it is to fear the Lord, we try to persuade others. What we are is plain to God, and I hope it is also plain to your conscience. We are not trying to commend ourselves to you again, but are giving you an opportunity to take pride in us, so that you can answer those who take pride in what is seen rather than in what is in the heart. If we are “out of our mind,” as some say, it is for God; if we are in our right mind, it is for you. For Christ’s love compels us, because we are convinced that one died for all, and therefore all died. And he died for all, that those who live should no longer live for themselves but for him who died for them and was raised again.

So from now on we regard no one from a worldly point of view. Though we once regarded Christ in this way, we do so no longer. Therefore, if anyone is in Christ,the new creation has come: The old has gone, the new is here! All this is from God, who reconciled us to himself through Christ and gave us the ministry of reconciliation: that God was reconciling the world to himself in Christ, not counting people’s sins against them. And he has committed to us the message of reconciliation. We are therefore Christ’s ambassadors, as though God were making his appeal through us. We implore you on Christ’s behalf: Be reconciled to God. — 2 Corinthians 5:11-20

We are sacred new creations. Sacred ambassadors. Serving a king crucified by the government he came to visit. Let’s start acting like it. Dying for it. Compelled by the love of Jesus, not by protecting our privilege (and even if that isn’t our motivation, the appearance that we’re doing that must push us to behave differently). Giving up commending ourselves in order to commend Jesus, and as Paul put it a chapter earlier ‘carrying around the death of Jesus in our bodies so that the life of Jesus might be made known’… whether we’re clergy or bakers, or candlestick makers.