Once upon a time there was a boy. He believed the bright lights of the big city and the experiences on offer there would allow him to be truer to himself than the life he had been born into.

He was born to a farmer, all his life to this point he’d been playing out the role he was born into. He found that role stifling. Sure, it involved the promise of one day owning a share in the farm — its success was his success. Sure, it involved security, and family life, and knowing who he was… but the order the lack of choice. This life was oppressive and he had to get out. He had to be free to choose his own destiny. His own identity. So he cashed in his shares from the farm and followed the lure of the bright lights; the city lifestyle he’d seen in advertisements that offered him more than he could imagine. So much choice. The ability not just to experience pleasures previously denied; this wasn’t just about hedonism, but freedom. He could be his own man. He could make choices. He could buy what he wanted, spend time with who he wanted. He was an heroic individual escaping a tired regime, aided by the voices of those who would help him be free as he made his informed consumer decisions to express himself as he fulfilled his every desire.

But then, the money ran out. When that happened he found that the companies that had promised so much — promised to be there for him — were no longer interested. He was no longer in the thick of the action in the big city. And even if he had the money to satisfy his desires, that had all proved less lasting — less good — even, than he imagined. He’d found himself addicted to the fast life; addicted to expressing himself and experiencing momentary pleasure; and he’d ended up essentially giving his whole life, everything he’d worked for, in pursuit of this pleasure to these companies that had promised so much, but delivered nothing.

The fast food and fast women he’d enjoyed with his money didn’t just disappear. In hindsight, the choices he made and the disappointment he felt when they didn’t satisfy left this boy questioning whether they tasted that good at all; they certainly were insubstantial and the flavours had nothing on the flavours that came from a home cooked meal served for him by a family that loved him. The fast food from the big city had an emptiness about it; no nutritional value; nothing lasting. As the city rejected him the boy found himself at its margins; unable to be ‘truly human’ on its terms because he now no longer had power, the boy started tending to the animals that would one day be slaughtered to serve up with eggs. He was once the image of success; an image he projected for himself; now he was beastly. Feeding the pigs and desperate to eat of their food; to become beastly, only, he already had, as a piece in the machine that fattened up pigs for market he was already no longer a free person exercising choice. He was a slave. Robotic. A part of the system.

The boy wished he’d never bought into the hype. Those companies didn’t love him. Their success — and the success of those who owned them, with their big houses and lavish lifestyles, didn’t want him to succeed, they wanted him to be a consumer so that they could consume him. Suck the marrow from his bones, while he ate swill.

This, of course, is something like a parable Jesus told. But it’s a parable for modern times too.

Watch this.

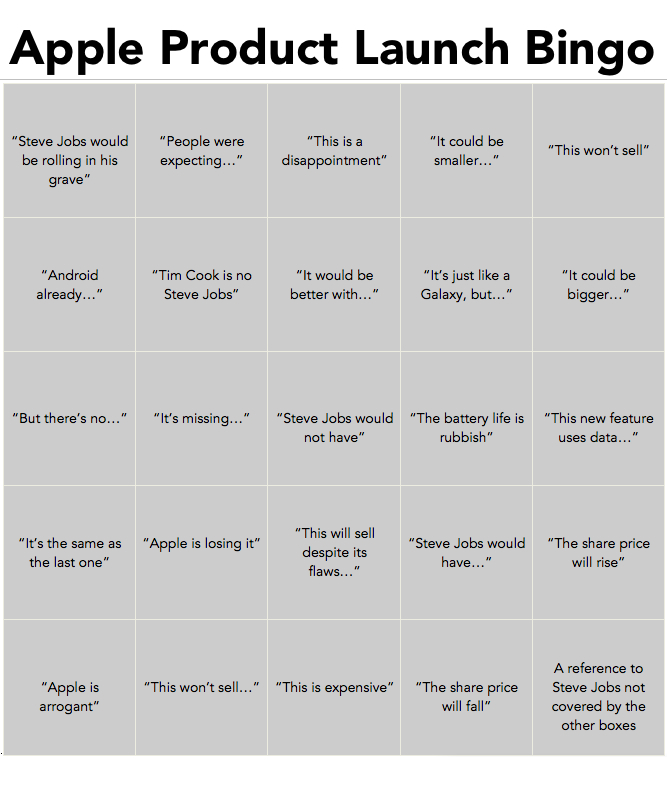

Get the message. These companies have ‘always been there’ for you. On your side. It’s corporations that take care of people — families — as we consume our way to the good life. In times like these, these ‘uncertain times’ — this pandemic — it’s companies who are there for us. In our homes. We can consume even while social distancing. Because these companies are here for us. As they have been for decades… We can count on them to help us get through this. Apple’s ad was, I thought, particularly inspired, and kinda beautiful, even if a picture of how much technology has ingratiated itself into our modern lives.

It’s Apple’s products, of course, that promise to bring us together, much like Telstra suggests it does in its magic of technology ads.

These companies offer the lure of bright lights and pleasure and security and all the tools one needs to survive and thrive as we consume our way to pleasure and express the real us in the midst of this pandemic.

Alongside Arundhati Roy’s optimistic dreams that this pandemic might bring with it a ‘new creation’ where people are kinder and gentler to each other; the sort that requires significant disruption to the status quo (and a ‘probably impossible without a shared grand narrative’ end of the culture wars), I read this piece about those forces — the status quo — that don’t want disruption, and how the manipulation required to stop disruption happening is going to begin with ads just like these from companies who do not want your individual consumer behaviour to change; because they want to keep you desiring things and pursuing the fulfilment of those desires through consumption as they sell you pig swill dressed up as a banquet. The article, Prepare for the Ultimate Gaslighting, says:

Billions of dollars will be spent on advertising, messaging, and television and media content to make you feel comfortable again. It will come in the traditional forms — a billboard here, a hundred commercials there — and in new-media forms: a 2020–2021 generation of memes to remind you that what you want again is normalcy. In truth, you want the feeling of normalcy, and we all want it. We want desperately to feel good again, to get back to the routines of life, to not lie in bed at night wondering how we’re going to afford our rent and bills, to not wake to an endless scroll of human tragedy on our phones, to have a cup of perfectly brewed coffee and simply leave the house for work. The need for comfort will be real, and it will be strong. And every brand in America will come to your rescue, dear consumer, to help take away that darkness and get life back to the way it was before the crisis. I urge you to be well aware of what is coming.

For the last hundred years, the multibillion-dollar advertising business has operated based on this cardinal principle: Find the consumer’s problem and fix it with your product.

These ads are the precursor for this project. Peddling the idea that consumption of products — participating in ‘the economy’ — is going to fix our problems.

Look, here’s a disclaimer, I worked in a marketing adjacent role (public relations). I loved it. I believed in what I promoted. Not all marketing is bad. Some products and services are good for you and it is good for you to know about them; but, on the whole, advertising and marketing are the prophecy and evangelism arms of a greedy consumerism that is bad for your soul. It’s possible not to sell or destroy your soul in a capitalist world, it’s just really hard (camel through the eye of the needle hard). Marketing and advertising can be used for good, but as a Christian I want to note that there’s a hint of advertising in Genesis 1, where God declares things ‘good,’ and more than a hint of advertising in Genesis 3, where the serpent creates a desire and sells a product to Adam and Eve.

It’s interesting for me, as an employee in the institution that once occupied this place in the cultural landscape, or the collective psyche, the place that offered comfort and hope in a crisis; and the stability of having been around for a long time… to see companies now jostling for the position the church once occupied. This fits neatly with Charles Taylor’s ‘secular age thesis,’ as I’ll outline below. The nutshell of Taylor’s thesis is that one of the social changes that produced secularism is the explosion of options we have post what he calls ‘the nova’ — options we have to pursue our own authentic self, freed from traditional power structures (and being ‘born into’ a particular station) we now define who we are; we choose our own identity, and we often express this through consumption of the things that we believe are good and true to ourselves. Corporations then play the role of priest, and shops function as temples, advertising becomes prophetic.

There are three take homes for me from this ad.

One, it reveals not a lack of imagination on behalf of the advertising industry; it’s a sign that the corporate world is on message. And its message stinks because it is selling slops not really fit for pigs, let alone humans, designed to fatten you up, so this little piggy can go to market. They’re trying to convince you, in essence, that the little piggy goes to market to buy stuff, which is a naive reading of that nursery rhyme, rather than to be slaughtered and turned into ham. The whole enterprise of finding meaning through consumption of products aided by corporations is hollow and rotten. People have turned from the church in the west for good and understandable reasons; but to turn to consumption and the pursuit of individual authenticity and freedom through consumer choice — that’s made a bit ridiculous when we see what looks like a smorgasbord of options is just the same swill served up in different packaging. There is nothing truly satisfying on offer from the ‘big city’ with its bright lights, desire creation, and consumption.

Second, these companies are part of an economic status quo that will do its best not to be disrupted by this pandemic; they’ll be pouring resources into advertisements and lobbying to get us consuming once again. Because the way the world was set up pre-pandemic relies on these companies occupying a particular place in the landscape. They’ll keep dressing up pig swill as a gourmet meal (the same one over and over again), but it will still be pig swill, and this is an opportunity for disruption.

Third, it’s a mistake for us in the church to think that the way back to relevance for the church is to play the consumer game; to offer ourselves as another option in the pig pen. Our job is to disrupt by playing an entirely different game; not the game where we’re pigs fattened for market to be killed, but children loved so much the father sacrifices a lamb to welcome us home. This comes with an entirely different pattern and pace of living and a different framework for understanding goodness and satisfaction.

Consumer life in the Secular City

Taylor describes the basis for the secular age we now live in as the ‘immanent frame’ — that is, a view of reality that excludes the transcendent (the realm of gods or spirits or non material reality). This is a relatively new thing (which is why it’s interesting to hear companies in the video proclaiming how long they’ve been serving the community, and the oldest you get is ‘over a hundred years.’

In this immanent frame, the previous social and religious ordering that gave rise to meaning, especially the sort of meaning that might help you through a crisis (whether superstitious, or pagan, or Christian, or a combo of all three), are gone and we are left to make meaning for ourselves. We’re cut off from God or gods, freed(ish) from inherited social obligations, free to make our own choices and choose our own adventure. Basically, the immanent frame makes us all like the boy in our story, cashed up with an inheritance from a previous social order, and able to decide what to do next to make meaning for ourselves without dad (or God) telling us what we have to do now. Taylor calls the individual in this situation ‘the buffered self’ — the self shielded from external, coercive, forces.

This isn’t just about individual selfishness. Taylor suggests that for a society wide change in belief and behaviour to take place it has to be motivated by a shifting shared sense of what is good for people; and the shift is a shift against oppressive structures. Some of this is legit. I don’t want to live, for example, in a Feudal society where my station and my professional options are pre-determined by the family I am born into, or a caste system (which isn’t to say our society isn’t structured in similar ways within the rules of the game as the companies we’re talking about want us to play it; enslaved, rather than freed, by personal choice and consumption and only allowed to succeed if we play the game by rules determined by some other).

Taylor suggests our society has turned to authenticity and expressing our true self as the cardinal virtues, and that we use consumer decisions to both discover who we really are, and then to perform and project that identity into the world in order to be recognised.

The post-war era (the time frame that most of those companies in the ad launched) brought with it an ‘affluence’ and a concentration on “private space” where we had the means to fill our own spaces; our castles and our lives; with “the ever-growing gamut of new goods and services on offer, from washing machines to packaged holidays.” Taylor says “the pursuit of happiness” became linked to consumer lifestyles expressing one’s “own needs and affinities, as only the rich had been able to do in previous eras.” Children born after this period became a new youth market, targetted by advertisers as ‘natives’ to this consumer culture; those who would, by default, express ourselves by expressive consumer choice.

The ‘good’ of authenticity was mashed up with a culture of expressive individualism in a framework provided where consumption was the way to discover and reveal your true self. Taylor sees this particularly playing out in the realm of fashion; particularly when an individual makes a consumer choice to express themselves and their identity as belonging to some thing or other that is greater than themselves (a bit like social media likes and posts also work as the performance of one’s authentic self). This effect of shared expression through shared fashion — be it a hat, or Nike shoes (or an Apple product) — is amplified in public places like concerts (band t-shirts) and sporting events (jerseys) which provide additional meaning for our actions and expression, these expressions of solidarity in public spaces are important in the secular world; because they are essentially religious experiences. Where once we might have conducted such meaning making activities in pilgrimages or religious festivals, now we do so in an immanent frame, and it’s our shared consumer decisions (buying the same shirt, for example) that produce this impact. Such moments ‘wrench us out of the everyday, and seem to put us in touch with something exceptional, beyond ourselves,’ such that our consumer choices can sometimes in replacing what the transcendent once did for us (in terms of meaning making and connection) give us a haunting sense of what has been lost.

Experiencing this haunting, this sense of connection, those glimpses of the transcendent, may also be what fuels our consumption — and it’s kinda no surprise when those responsible for driving our consumption — advertisers — tap into that, with imagery (or iconography) and the sort of language and purpose you might once have reserved for religious organisations. Taylor says the result of all this is that:

Commodities become vehicles of individual expression, even the self-definition of identity. But however this may be ideologically presented, this doesn’t amount to some declaration of real individual autonomy. The language of self-definition is defined in the spaces of mutual display, which have now gone meta-topical; they relate us to prestigious centres of style-creation, usually in rich and powerful nations and milieux. And this language is the object of constant attempted manipulation by large corporations.

So we’ll either consume as an expression of tribalism where we can mutually display our belonging (like wearing a band shirt to their concert, or the shirt of our local football team), or with an eye to the life we wish we were living (like wearing a luxury brand, or a shirt bearing the logo of a company whose values and prestige we aspire to… and companies will fuel this dissatisfaction in us by seeking to create desires that only their product can fulfill (which is marketing 101).

Tech in the City

You can stack Taylor’s observations against the behaviour of companies a decade after he wrote A Secular Age (so, now). And start to bring in some observations here from other thinkers, especially about the role technology companies play in facilitating modern life. We can now perform our identities online, not just in the public square; which is what telcos are offering us (especially in a time of social distancing), what social media companies facilitate (via your ‘profile’ and your ‘feed,’ and what tech companies (like Apple) provide us with tools for (like phones with cameras). These companies, as much or more than bricks and mortar stores in public places, and large scale public gatherings (especially right now) are providing the ‘social imaginary’ for us, as well as providing the space for us to ‘be ourselves.’ Which is a problem if part of the ‘corporate status quo’ that is making a stack of money off helping us ‘express our true selves’ (and so enslaving us to their own oppressive system) is a sort of ‘Babylonian’ technocracy. I mentioned the ‘technocracy’ idea in yesterday’s post, where I linked to Alan Jacob’s piece about the over-promising made by the technocratic regime about the satisfaction technology might bring us. Neil Postman actually (I think) coined the term in Technopoly, where he described the way tools work in connection to our symbolic performance of things that give meaning. Postman said:

“In a technocracy, tools play a central role in the thought-world of the culture. Everything must give way, in some degree, to their development. The social and symbolic worlds become increasingly subject to the requirements of that development. Tools are not integrated into the culture; they attack the culture. They bid to become the culture. As a consequence, tradition, social mores, myth, politics, ritual, and religion have to fight for their lives.”

Postman, Technopoly

He sees tools — our technology — pushing into the vacuum Taylor observes in A Secular Age, the search for meaning in an ‘immanent frame,’ to become ‘the culture.’

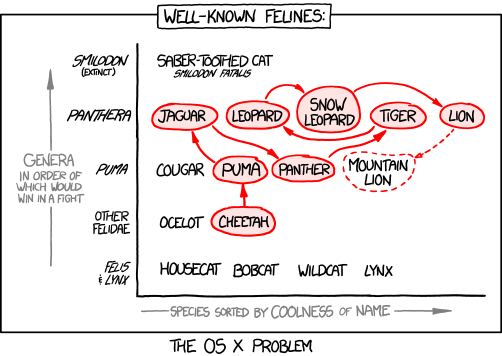

That quote is startling to read alongside the Apple ad above, given what it depicts and what it promises, but unsurprising… because commentators have long observed the religious function of Apple and its mythmaking engine. Marshall McLuhan (writing before Apple was a thing) suggested technology, especially communication technology that embeds itself in our ecosystems and our individual lives, functions religiously, that is, in a technopoly our technologies become idols. And these idols end up enslaving us.

“The concept of “idol” for the Hebrew Psalmist is much like that of Narcissus for the Greek mythmaker. And the Psalmist insists that the beholding of idols, or the use of technology, conforms men to them. “They that make them shall be like unto them… By continuously embracing technologies, we relate ourselves to them as servomechanisms. That is why we must, to use them at all, serve these objects, these extensions of ourselves, as gods or minor religions… Physiologically, man in the normal use of technology (or his variously extended body) is perpetually modified by it and in turn finds ever new ways of modifying his technology.”

McLuhan, Understanding Media

McLuhan also believed escaping this status quo will prove very difficult because of how embedded technology and consumption is in our modern life — and how much they reinforce one another until we become these robotic ‘servomechanisms’ — thoughtless consumers who can’t escape, and probably don’t want to…

“For people carried about in mechanical vehicles, earning their lives by waiting on machines, listening to much of the waking day to canned music, watching packaged movie entertainment and capsulated news, for such people it would require an exceptional degree of awareness and an especial heroism of effort to be anything but supine consumers of processed goods.”

McLuhan, Mechanical Bride

Scott Galloway, a tech pioneer, entrepreneur, and business academic wrote a book titled The Four, examining the big four tech companies that dominate our ecosystem: Apple, Facebook, Amazon, and Google. He viewed them all through a religious prism, and (following some stuff a while back by Martin Lindstrom around the brain activity of Apple users while interacting with its products mirroring the brain activity of religious people while practicing their religions), Galloway said:

“[Apple] mimics religion with its own belief system, objects of veneration, cult following, and Christ figure,” … “Objects are often considered holy or sacred if they are used for spiritual purposes, such as the worship of gods. Steve Jobs became the innovation economy’s Jesus—and his shining achievement, the iPhone, became the conduit for his worship, elevated above other material items or technologies.“

Scott Galloway, The Four

A call to (secular) worship

These ads aren’t just neutral. They aren’t just designed to keep the economy afloat and people in jobs. They are a call to worship. A call to not be disrupted. To keep eating the pigswill dreaming of a time when you might be at the centre of the city, not its margins, and telling you that it’s consumption that’s going to get you there as a consumer.

David Foster Wallace talks about this status quo in his famous speech This Is Water. He said this pattern of consumption; of worship; is the ‘so-called real world’ — our default settings. He said:

And the so-called real world will not discourage you from operating on your default settings, because the so-called real world of men and money and power hums merrily along in a pool of fear and anger and frustration and craving and worship of self. Our own present culture has harnessed these forces in ways that have yielded extraordinary wealth and comfort and personal freedom.

It was this siren call, the idea that he was missing out on the good life, that pulled the boy in our story from his father’s garden-farm to the bright lights of the big city. The call to fast food, fast women, and parties was an invitation to worship at a different sort of temple (and, you know, those activities were actually stock in trade for first century pagan temples). The boy in our story is invited to worship other gods, and they end up treating him the way the gods of other pagan nations, especially Babylon, treat people; as a slave.

Disrupting hollow gods

Our boy found himself feeding the pigs, on the outskirts of the big city.

One day, as he looked at the muck around him, as he noticed the slop looked a lot like the leftovers of the meals he came to the city to eat… he realised he’d been sold a lie. All it took was a momentary break; that moment where he pictured himself on his knees tucking in with the pigs. He new. He knew the city was turning him into an animal. In that moment, the emperor had no clothes. The bright lights of the city were flashy and distracting — just the right amount of visual noise and trickery to keep you from seeing the city’s ugly underbelly. He began to daydream; imagining himself back at home on the farm. The clean air. The clean living. The clean eating. Feasting with his family. Better to be a servant there, in a life giving system, than a slave here, on the path to being chewed up and spit out, he thought. So he hit the road. On his way out the billboards by the road started crowding out his vision; promising fast food; fast women; fast money; fast satisfaction. Doing all it could to claw him back. To gobble him up. He ran.

All he needed was a little disruption. And he was gone.

The city promised our boy freedom, only it didn’t offer real freedom, but a certain sort of slavery. This is the same deal our advertisers offer us now; it’s the same city. The same world.

This is a world that doesn’t want disruption.

This is a world whose gods are hollow; a world that tries to dress pig slop up on a big white plate as a gourmet meal. It’s a bit like Ephesus in the book of Acts — a world that pursues wealth and flourishing from making, marketing, and selling, silver idol statues; that feels very threatened when the hollowness of those gods is revealed by a God that actually offers satisfaction.

My favourite part of This Is Water is not the bit about how ‘everybody worships’ or the diagnosis of what flows from the worship of false gods (dissatisfaction). It’s that all these false forms of worship of things from within what Taylor calls ‘the immanent frame’ — the decision to, as Paul puts it in Romans, worship created things rather than the creator — leave us with a ‘gnawing sense of having had and lost some infinite thing,’ but also, that anything immanent we worship, and worshipping anything not transcendent will, in Wallace’s words “eat you alive.” Take that piggy.

Taylor describes this too; he says the turn to expressive individualism — to performing our ‘authentic self’ via consumption actually leaves us hungry. The promises of advertisers and their corporate masters do not satisfy our hunger; they are hollow. This is what the ad compilation reveals. The utter hollowness of the promises of the corporate world; the hollowness of the idea that companies and their products can be ‘there for us’ in a pandemic when we are fearing for our health and our lives, the emptiness of meaning that this turn from the transcendent to the immanent can provide… Taylor says this leaves us haunted and with a sense of lack; not just in those times were previously we’d have turned to religion to help us make meaning (key markers like births, marriages, and death) but “in the everyday” — and actually, it’s in the everyday where we might notice it most. It’s the idea that we feel the lack not just when we’re feeding the pigs from the margins; but right there with the bright lights, in the big city. The emptiness of what we’ve replaced God with bites just as hard as the hunger pangs in the pig pen. Taylor says:

But we can also just feel the lack in the everyday. This can be where it most hurts. This seems to be felt particularly by people of some leisure and culture. For instance, some people sense a terrible flatness in the everyday, and this experience has been identified particularly with commercial, industrial, or consumer society. They feel emptiness of the repeated, accelerating cycle of desire and fulfillment in consumer culture; the cardboard quality of bright supermarkets, or neat row housing in a clean suburb; the ugliness of slag heaps, or an aging industrial townscape.

Taylor, A Secular Age

Taylor says this is one of the things that keeps us from defaulting to unbelief in the immanent frame; there’s a contest, and it’s both the haunting — the sense there might be something more — and the hollowness — the “nagging dissatisfactions” and the rapid wearing out of the utopian visions the prophets of the immanent frame cast. It’s precisely moments like this ad montage that pull back the curtain and throw some of us towards faith in something other than consumption.

Stopping to see the cost of the status quo — the price it makes us pay as little piggies — has the capacity to disrupt us. That’s the point of the gaslighting article linked above, and the quick pivot to advertisements announcing that companies are “here to help.” To keep us blind.

Big business is going to want us to forget the almost immediate impact on our natural environment that our scaling back consumption has had. And it’s not just the environment that has felt some of that oppression lift. I’m seeing lots of appreciation for the way this crisis has pushed us towards local relationships. Kids playing on the street. A return of the neighbourhood or village. Taylor saw the ‘nova’ — this explosion of possible choices — produced by technology and cultural changes that allowed us to escape the village. “The village community disintegrates,” first through the “age of mobilisation” and then the “nova” as people are able work and live in different locations, or as people uproot for sea-changes or to pursue employment wherever they choose (again, not all of what he calls the ‘age of mobilisation’ or the ‘nova’ is negative, but our ability to ‘choose’ previously unthinkable options does produce change to village life).

They’re going to want to keep us from finding meaning in village and communal life, so that we’re back stocking up our private castles. Apple can’t make money from me talking to my neighbours. They’re going to want us to slip back into the pursuit of meaning and desire-fulfilment that their machinery creates in order to satisfy its own hunger. It’s not relationships that satisfy, but relationships-completed-by-products that satisfy…

The ‘status quo’ that makes money and gains power from the system staying the same is under threat; disrupted by a pandemic. The cracks are showing, so they’re returning to what they and we know. Inviting us to consume our way to comfort. Reminding us that “they” are there for us (I mean, Lexus has a TV ad inviting me to call them if I want a chat — although this is probably just for people who own a Lexus)… And we shouldn’t let them get away with it.

And more than that, we, the church, should not participate in this system as another product to be consumed, but as disruptors. Like Paul in Ephesus.

Lots of the stuff I’ve been trying to articulate in my last few posts about our need to resist the siren call of technology has been a call to be disrupted by Covid-19 so that we can become disruptors in this manner.

We can’t be like the advertisers offering up Christianity as just another form of pig food, or fodder from a food truck in the big city the prodigal ran to (prodigal means ‘wasteful’ not ‘runaway’ by the way).

We can’t think the way to be an ambassador for home style farm life is to become card carrying citizens of the system; not from home. We’re the farmers coming to town for a farmer’s market, in our farm gear, with our country pace — not salespeople trying to compete ‘like for like’ with McDonalds. We’re trying to pull people out of the immanent frame, not playing in it as though that’s where satisfaction and the good life is to be found.

We must be people who take the opportunity to expose the hollowness of false gods and their noisy prophets. Prophets who without getting together to plan, all produced messages from the same boring song book. These ads are a stark reminder of the emptiness of what expressive individualism based on consumption offers. A haunting moment.

We must be people who point to the redemptive power and value of a home cooked meal with the God who loves us; people who point beyond the immanent frame our neighbours want to live in to the transcendent reality; that there is a God who is not just our creator, but our loving father who wants us to share in his task of cultivating life and goodness in the world.

The problem is, for much of the period the companies in the ad above have been operating (so not for very long — that is, in the post-war period) the church has positioned itself as just another consumer choice in a world where our identity is chosen and performed, rather than as an entirely different way of being. Church has been treated by just one other consumer option, and we’ve jumped in to play that game.

We’ve served church up on the buffet next to other consumer decisions, and so cultivate the idea that we’re just another attraction alongside the bright lights in the big city, and so have become a slightly more nutritious form of pig food; more fodder that just reaffirms that the good life is found in expressive individualism performed by consumer decisions.

Taylor describes this step that kicks in once religious life is approached in these terms:

“The expressivist outlook takes this a stage farther. The religious life or practice that I become part of must not only be my choice, but it must speak to me, it must make sense in terms of my spiritual development as I understand this. This takes us farther. The choice of denomination was understood to take place within a fixed cadre, say that of the apostles’ creed, the faith of the broader “church”. Within this framework of belief, I choose the church in which I feel most comfortable.”

We treat church like a product, culturally, and so churches start acting like products — or like corporations. Imagine what happens there when church starts to be advertised like every other product. Imagine if you were presenting your online church services in much the same way that products are selling themselves during Covid-19.

Our church has been around for x years. In good times and in bad. We’ve always been here for you and your family. Now more than ever. We might be socially distanced, but you can enjoy God, and our live streamed services, from the safety and comfort of your home… press like to come home. God will see you through these hard times, and will be there still when we get back to normal… we’re here to help…

Applause

Pig slop.

Or at least indistinguishable from pig slop; even it it’s all true. It’s certainly not disruptive; it buys into the idea that church is a consumer decision that will allow you to be your true self. And I reckon I’ve seen a bunch of variations of this theme. People seeing Covid-19 as an opportunity to reproduce the status quo; just digitally.

This is especially true for those churches that have bought into the “technocracy” and the age of expressive individualism and so gone to market to shape church as a desirable big city option, rather than a taste of home on the farm with the father.

The church growth movement and the sort of toxic churchianity that it produces, which then leads us, in a time of crisis, to turn our services into shows that can be consumed using the same technology we use to binge entertainment, buy stuff, and satisfy all sorts of other desires at the click of a link is disrupted church rather than a disrupting church. A church shaped by the ‘nova’ and playing in the immanent frame trying to win consumers. Taylor says this approach produces a spirituality that is individualised, superficial, undemanding, self-indulgent and flaccid.

This is not who we are; at least it’s not who we are meant to be. The whole expressive individualism via consumption enterprise is not who we were meant to be; and that’s part of what we’re experiencing now. The best application of Taylor’s A Secular Age to today’s technocracy that I’ve read is Alan Noble’s Disruptive Witness. It’s a call to a thicker, non-consumer oriented, practice of Christian witness in an age where the good life is thought to be caught up in ‘authenticity’ and expressive individualism through consumer choice, and where the church has too often pandered to that framework. He suggests a series of disruptive practices we might adopt, but one of his main points is to stop playing the game of approaching our witness like marketers selling a product. He thinks at the very least a deliberate stepping away from the methodologies of the church will protect our witness so we might disrupt some lives. He said:

“As the church has taken more and more of its cues from a secular, market-driven culture, we’ve picked up some bad habits and flawed thinking about branding, marketing, and promotion. We’ve tried to communicate the gospel with cultural tools that are used to promote preferences, not transcendent, exclusive truths.”

What I found interesting when digging back into the book today, was that his criteria for widespread disruption might just be being met (and this might be why the gaslighting article is worth heeding).

“If history is any indication, the distracted, secular age can only be uprooted by a tremendous historical event that reorders society, technology, and our entire conception of ourselves as individuals: something like the invention of the printing press, the protestant Reformation, or a global war — a paradigm shifting event. But trying to correct the effects of secularism and distraction through some massive event is quixotic at best and mad scientist-is at worst. This leaves us in a difficult position. There is no reasonable, society wide, solution. Which is not to say that we can’t ameliorate the problem through policies and community practices.”

Alan Noble, Disruptive Witness

There is an opportunity here for us to be disruptors rather than disrupted.

If your church’s response to Covid-19 is to produce anything that looks like these ads, or that plays in the same frame that they do, then you’re doing it wrong.

Our response to Covid-19 can’t be to think ‘how will I turn this into an opportunity to sell my product to people who are scared,’ our response isn’t to get people to add Christianity to their array of consumer choices in the city, a city that wants to fatten them up as piggies going to market, but to invite them to run back to their heavenly father, who loves them, who waits with open arms, who’ll kill the fattened calf (or the lamb) to bring them home.

The boy had been walking for some time. Finally the landscapes around him were familiar. It was getting dark; but that was ok, darkness actually meant the bright lights of ‘sin city’ were a long way behind him. He already felt human again. He found he had no desire to eat pig food. Progress, he thought. His speech for when he came face to face with the father he’d abandoned was running through his head. To take his inheritance and squander it, ‘the prodigal,’ was to say to his dad ‘I wish you were dead,’ he was sorry. He set the bar low; “I’d rather be a servant than a pig being fattened for slaughter” he thought.

The father had been sitting on his front step each day since his son left. Waiting for his son to return; hoping that the light and life and love of home would be enough to bring his son home; knowing that the city talked a good game but that it only offered emptiness; hoping his son had not been destroyed by the endless pursuit of more. He looked up, and saw a figure on the horizon. It’s my son, he thought. The city hasn’t been kind to him. He called to a servant to butcher a calf in the field, and to start preparing a feast. Then ran to his son. Embracing him before he could speak a word.

The boy was home.

The Gospel is not pig slop. We should stop treating it like it is.