Galatia. A place Paul wrote to. That’s about all I know about Galatia, not having been there. Except that Galatian Christians faced much the same problem from Rome as Christians throughout the empire. Which is where this post is heading. I’m finally finding a use for the extended edition of an essay I wrote last semester (the extended edition was twice the word limit, I removed half the essay and handed it in – taking out pages at random1). Eagle eyed readers will notice the same clump of references regarding the legal status of Christianity that featured in the last post. It’s from a different essay. I aim to include them in every essay I write for Bruce (3 out of 3 so far)2.

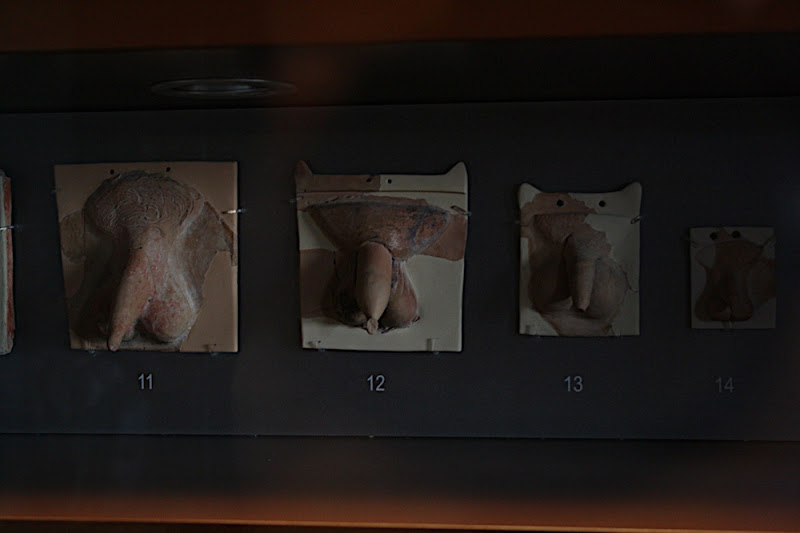

Basically, one of the issues going on in Galatia is circumcision. Sometimes you just have to cut to the chase on these things. Romans weren’t circumcised. As demonstrated by this picture that Facebook flagged as inappropriate.

Romans weren’t circumcised, but Jews were – which meant that Roman converts to Christianity could literally blend in by getting the snip (really? How literal is that? Did they invert their clothing in the first century? Covering everything but their bits?). Well no. But Romans thought circumcision was an abominable practice, and they tolerated it in Jews but abhorred it personally – and it was a real marker of converting to Judaism, which earned one exemption from the Imperial Cult, and thus freedom from some of the persecution that came from converting to Christianity. Below you’ll find my take on the issue from the essay I hacked to pieces (the footnotes are there so you can dig up Bruce’s article on the matter – except I can’t find it on google, I think last time I found it I found the book of the proceedings of the conference it was presented at somewhere on the interwebs), it was more than possibly identical to whatever handouts he gave us in class. Anyway, here are some bits and bobs:

The question of references to the Imperial Cult in Galatians is a Jewish question. Winter’s (2002) thesis on the motives behind Jewish agitation in Galatia (Galatians 6:12) is that Jewish Christians were encouraging gentile converts to use Jewish camouflage to avoid participating in imperial cult, or persecution for failing to participate.[1] Jews in the Roman Empire are understood to have been exempt from cultic practices, free instead to practice their own religion.[2] This freedom varied from emperor to emperor, and region to region. There was no written charter providing such freedom.[3]

Josephus and Philo record that the Jews abrogated their cultic responsibilities by offering sacrifices for the emperor,[4] Herod, not content with this arrangement, built three temples dedicated to the emperor and Rome, McLaren (2005) suggests honouring the cult was a major priority in Judea.[5] This did not prevent the use of the cult as a weapon in Jewish-Roman relations.[6]

Winter (2001) argues that Gallio’s decision (Acts 18:12-17) initially served to protect Christians from participating in the Imperial Cult under the mos maiorum, and Gentile converts to Judaism were recognised as Jewish by imperial law.[7]

Hardin (2008) in his extensive treatment of the situation follows Winter, adding a minor addendum to reflect his findings that the Jews actually participated almost fully in the practices of the Imperial Cult. He suggests Christians were in no man’s land – neither Jew, nor gentile, and that the agitators, Jewish converts, wanted the church to pick a side.[8] He concludes his monograph by suggesting that the imperial cult forms an important backdrop for the study of Galatians, and the New Testament as a whole.[9]

[1] Winter, B.W, ‘The Imperial Cult and Early Christians in Roman Galatia (Acts XIII 13-50 and Galatians VI 11-18),’ in

Actes du ler Congres International sur Antioche de Pisidie, eds., T. Drew-Bear, M. Tashalan and C. M. Thomas: Iniversite Lumiere – Lyon 2 and Diffusion de Boccard, 2002, 67-75, This thesis finds some support from Stanton, G,

Jesus and Gospel, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 2004, pp 43-46, and Hardin, J.K, ‘Avoiding Persecution and the Imperial Cult,’

Galatians and the Imperial Cult, (Tubingen: Mohr Siebeck), 2008, pp 85-115

[2] Letter of Claudius to the Alexandrians, Papyrus found at Philadelphia in the Fayum, Egypt, The Roman Empire: Augustus to Hadrian, ed. and trans. Shrek, R.K, pp 83-86 – “Therefore, even now I earnestly ask of you that the Alexandrians conduct themselves more gently and kindly toward the Jews who have lived in the same city for a long time, and that they do not inflict indignities upon any of their customs in the worship of their god, but that they allow them to keep their own practices just as in the time of the god Augustus, which practices I too have confirmed after hearing both sides”

[3] Rajak, T, ‘Was there a Roman Charter for the Jews?’, The Journal of Roman Studies, Vol 74 (1984) pp 107-123, Pucci Ben Zeev, M, ‘Jewish Rights in the Roman World – The Greek and Roman Documents quoted by Josephus Flavius’, 1998, Mohr Siebek, pg 412, Rutgers, L.V, ‘Roman Policy Towards Jews’, Judaism and Christianity in First Century Rome edited by Donfried, K.P and Richardson, P, pp 93-116, one only needs to consider Caligula’s aborted attempt to hijack the temple, and its destruction under Nero to accept this point.

[4] McLaren, J.S, ‘Jews and the Imperial Cult,’ p 271

[5] McLaren, J.S, ‘Jews and the Imperial Cult,’ p 259, these temples were constructed at Caesarea Maritima, Sebaste, and Banias

[6] McLaren, J.S, ‘Jews and the Imperial Cult,’ p 262, Imperial cultic requirements were a flashpoint. The Greek citizens of Alexandria triggered the incident leading to Claudius’ missive by erecting statues of the emperor in the synagogue. If the Jews removed the statues this would be seen as imperial impropriety, Josephus’ account of the incident suggests the Greek citizens used the cult as a weapon, Pilate also caused some consternation in Judea by introducing inscribed shields to Jerusalem, see Fuks, G, ‘Again on the episode of the gilded Roman shields at Jerusalem,’ Harvard Theological Review, 75 no 4, 1982, pp 503-507

[7] Winter, B.W, After Paul Left Corinth, (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans), 2001, pp 278-280, Winter, B.W, ‘Gallio’s Ruling on the Legal Status of Early Christianity (Acts 18:14-15),’ Tyndale Bulletin 50.2 (1999) 213-224.

[8] Hardin, J.K, ‘Avoiding Persecution and the Imperial Cult,’ Galatians and the Imperial Cult, (Tubingen: Mohr Siebeck), 2008, pp 85-115

[9] Hardin, J.K, Galatians and the Imperial Cult, p 155

1 That is simply not true, and I apologise for the dishonesty.

2 That is actually true.