It’s more than possible that I have posted this exact infographic previously. But I like it. It’s about coffee. And it is interesting.

From Mint.com.

It’s more than possible that I have posted this exact infographic previously. But I like it. It’s about coffee. And it is interesting.

From Mint.com.

Fairtrade is good. Direct trade is better. Fair trade sets a price for farmers above market value for farmers who agree to meet certain conditions (like paying their workers, joining a co-op set up, not using pesticides… etc). Direct trade is where coffee roasters strike deals with farms which ensure a quality income and quality output are much better for the farmer and the end user. You. The drinker.

Here’s a description of the issue Fairtrade aims to solve. A glut of producers have moved into the market and flooded the world with sub par coffee at cheap prices. Traditional coffee producers lose out, because coffee production is suddenly a worthwhile industry…

The problem is what is known as the international coffee crisis. Simply put, there’s too much cheap coffee flooding the market these days. It comes from countries such as Brazil and, more recently, Vietnam, which have been using massive agribusiness techniques. Record low coffee prices have devastated long-standing coffee producers such as Guatemala. Coffee was once the country’s No. 1 source of cash — now more money comes from emigrants sending money home from the United States.

Here’s what this situation means for coffee producers (from an article from 2003):

The coolest bit about this article is the little program that lets you decide how much money you think each entity in the coffee process should get from every coffee dollar you spend…

One of the things I’ve noticed in the course of my daily working life is that taking out the middle man is the new black. Direct distribution from wholesaler to purchaser is best. Taking out layers of middle men is preferable. Because producers and users get a better deal. I’ve noticed that a lot of printing companies that used to be niche printing companies are hiring designers and calling themselves one stop shops for design and printing. It makes sense. They get two bites of the cherry. They get their standard printing jobs from other designers while at the same time trying to undercut their design business…

It works for printing companies – it also works in coffee. Coffee roasters buying direct from growers is the best way forward for both quality of coffee and quality of life for those growing it.

One of the perks of my job is the quantity of industry publications that land on my desk for me to read. This month’s FoodService – a journal for hospitality businesses – includes some facts and figures about coffee. I thought I’d share them with you… they’re from BIS Shrapnel’s Coffee in Australia 2009 – whatever that is…

Milk Facts

Purchasing Rationale

Former WBC champion James Hoffman has written an interesting post on the cost of coffee in your average cafe… He makes an interesting comparison between the price of espresso and the price of other high market beverages… he makes the point that most recession survival guides suggest cutting coffee out of their diets, and little wonder…

“Let’s say a single espresso in London costs £1.50, which is a little high but not by any means unusual. Assuming it is a 25ml shot that works out at 6p/ml.

If you were to go to a pub and buy a pint of espresso it would cost you £34.08. Or you bought a wine bottle of espresso it would cost £45. That is a phenomenal amount of money. Think about the drinks you can buy for that sort of price. They are either extremely delicious or extremely alcoholic.”

Which creates its own problems…

The problem is that a price tag like this is a pretty hefty promise. Selling an espresso for this much implies that the experience will be of equal value. Sip for sip it should be as satisfying as a great champagne. The problem is that in this country, in London, in the vast majority of businesses – it isn’t.

Charging this much and delivering something so awful as the average high street espresso destroys any trust between the coffee industry and the general public. This kind of price/experience discrepancy makes people feel stupid. It makes them resentful.

He suggests that this equation should lead towards the proliferation of brewed coffee, I’d suggest the best way to save money on coffee in a recession (and any time in fact) is to roast your own beans and make your coffee at home.

I can’t help but wonder why this plantation isn’t named “sky berry” coffee plantation – given the elevation and the fact that coffee starts off as a berry. But who am I to pass judgment on a name…

I’d been looking forward to visiting a coffee plantation for a while – and the Skybury experience doesn’t disappoint (except perhaps for the coffee at the end). The Zimbabwean owner has big dreams for his farm – which is home to the Australian Coffee Centre. There’s a “Material Change of Use” notification in front of the shed and our guide mentioned plans for a luxury hotel, and it’s certainly beautiful countryside.

The plantation tour was informative – did you know for example that the average coffee tree will produce 7kg of coffee berries per year, and those will result in 1kg of green coffee beans after processing, and that will result in about 850g of roasted coffee, which will result in about 47 double shot coffees. Skybury removes coffee trees every seven years – and only harvests them in their third year of existence – that’s four years of production per tree – or 188 coffees. That’s a high end estimate because there’s a fair bit of sorting that happens between tree and cup – with a lot of beans literally not making the cut. Any beans that don’t meet particular shape, size and density requirements slide of the shaking mechanical graders and become fertiliser – or worse, instant coffee.

The owner of Skybury has also developed a revolutionary piece of harvesting technology – which is best described as a carwash like machine that thwacks the berries off the tree and collects them in a container. This is a significant improvement on handpicking – one person handpicking coffee will harvest about 12kg of green beans per day (that’s 84kg of berries) – half a 25kg coffee sack, a mechanical harvester will harvest 8 tonnes of green coffee in a day – 320 25kg sacks in a day.

Australia produces about 200 tonnes of coffee annually, peanuts as far as exports are concerned… Skybury produces more than half our annual exports. They’re a major player in a pretty small pond on the global scale.

Australian beans are in demand though – the quality control employed in our processing of beans means Skybury sells its beans to the international coffee market at about 3 times the price I pay for my green beans.

The post tour coffee wasn’t the best (or worst) I’ve ever had. It was a cappuccino with no foam at all. It seems Queensland coffee naturally comes in at either extreme of the froth spectrum if you don’t get served an iceberg sized ball of froth you get a millimeter of microfoam and coffee diluted by watery milk.

Discussion is ongoing on yesterday’s post about protectionism and misguided “buy local” campaigns. I didn’t mention the “sustainability” side of that debate – which is probably valid. It doesn’t make sense for major grocery stores to ship produce from North Queensland to warehouses in Victoria then back to North Queensland for sale – at that point I will join the brotherhood of sustainability and cry foul (fowl if we’re talking about chickens…). I didn’t mention it because it’s not the problem I have with “buy local” campaigns – which is that they don’t do what they claim to do, namely “protect local jobs”.

Buying local works to protect Australian farmers. There’s no denying that. But the insidious campaigns stretch further than the farm gates But we have plenty of other primary producers whose cause is harmed by drops in demand for our resources overseas (which are in part due to drops in demand for all sorts of product on a global level – particularly from the US).

But that’s just rehashing the point I’d already made yesterday. In a slightly more coherent form.

There were a couple of points raised in the comments that are worth rehashing – particularly if you haven’t read them.

“Buying coffee grown in Australia at a local coffee store, rather than coffee grown in Costa Rica at Starbucks.” – Stuss.

Ahh, a subject close to my heart. The argument I’d make at this point is that Australian made doesn’t necessarily guarantee quality. You might feel nice paying three times the price you’d pay for foreign grown produce for local stuff – but in some cases you’re paying more for an inferior product. Coffee is a great example. If you want premium quality Australian coffee you’ve got to pay a premium price – and it still won’t be as good as stuff grown in the ideal conditions.

Her next point in a subsequent comment touches on the whole fair trade debate.

“There are ethical implications in buying goods made elsewhere. A big reason why companies shift that manufacturing off shore is that it can be done cheaper. Much, much cheaper. Which means the people doing the manufacturing aren’t getting a lot of money for the job. On one hand, it is good that some of these people are getting the employment at all. But on the other hand, sometimes these people are being exploited, and not receiving a fair wage. Or they are coming away from their villages and subsistence farming lifestyle to work in the factories and losing traditional skills. Which one outweighs the other?”

Those sweatshops employing and exploiting workers for the sake of fashion are a different matter, that’s an ethical question not a question of economics – and therefore not within the scope of this rant.

I don’t see how buying local and doing these overseas people out of the jobs they’ve won that are often literally putting food on the table – particularly when following through the argument using coffee farmers as an example – is doing the coffee farmer a service. In the case of agriculture – and particularly for argument sake the case of coffee – we’re not talking about farmers leaving subsistent living, we’re talking about third and fourth generation farmers who have been exporting coffee since coffee exporting began. Aussie Joe who decides to plant his coffee plantation in Atherton – where conditions aren’t as good as conditions elsewhere and thus the coffee flavour isn’t as rich – is doing a disservice both to the palate and to the global coffee market.

The fundamental economic principle of supply and demand means that if there’s an oversupply of a poor quality version of a particular variety of product and a largely uneducated audience the price of the good stuff either has to significantly alter or die out (or become an “exclusive” product for the rich and famous). Throwing in a “buy local” campaign artificially inflates the price of local coffee and punishes the foreign growers. It’s not a level playing field. And it’s an incentive for businesses that should probably fail. Because their product is inferior.

Amy made a similar point about rice but from a sustainability rather than quality standpoint in the comments on the last protectionism post…

“I don’t think it is okay to buy Australian grown rice, because rice is totally unsuited to our environment and therefore needs far more resources than an imported product.”

I wonder what the typical elements in the purchase equation are? You could no doubt express it as a funky Venn diagram – in fact I’m sure it’s already been done somewhere… but I’d say price, sustainability, ethics, and quality are all in the mix. Are there any others?

Here’s an interesting coffee article with the following environmental and economical message:

“Last year, Britons spent about £750 million on coffee, but only a small fraction of this on espressos. Think of the huge amount of money that would be saved if the majority of coffee-bar patrons switched to espressos from cappuccinos. The country’s milk bill would fall and its carbon footprint would shrink too.”

Not only is coffee an excessive drain on water stocks – milk is bad too. This is all very well – except the same writer also describes the cappuccino experience (amongst others – including the corretto – a shot with alcohol)

“There is no doubt that the most popular variant is the cappuccino (“little hood”), at its best a glorious drink consisting of equal parts espresso, milk and foam. The experience of consuming a perfectly made cappuccino is sensual to the point of decadence.”

500 billion cups of coffee are consumed globally every year. It’s big business. And you thought I’d chosen such a niche topic to keep writing about.

The coffee industry is facing problems though. The tough economic climate means people are cutting back on expensive coffee, and even drinking instant. Partly thanks to Starbucks’ new instant product. Via. Which gives me one of those involuntary shudders.

This discussion – particularly the impact of the economic climate on coffee purchasing – was the topic of a recent post from Hungry Magazine.

“VIA™ also focused me on what’s not happening at the local level. If you recall, I mentioned I just drank French pressed whole bean grocery store bought Starbucks. Up until a few months ago I was an exclusive Intelligentsia and Metropolis coffee drinker. But with the economy tugging at me and 12 oz of locally roasted beans costing $11.99 or so, I started experimenting with the $8.99 and $6.99 options available at the grocery store. I was convinced I’d probably end up where I started from, but I needed to see what was out there.”

The post drew some interesting comments from the CEO and bean buyer from Intelligentsia Coffee – arguably the pinnacle of the “specialty coffee” movement.

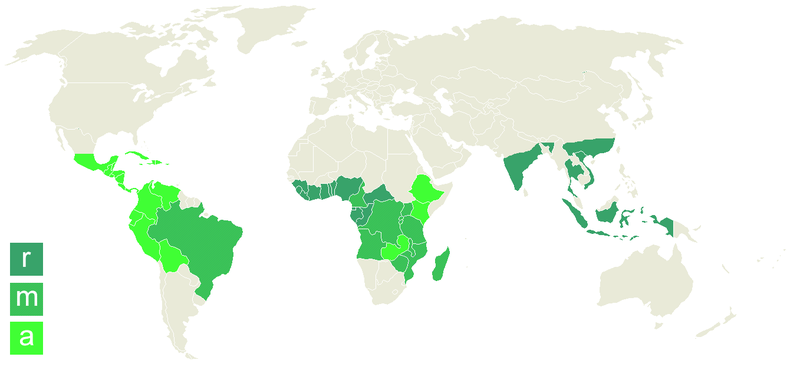

One of the economic problems facing the coffee industry is best expressed by these two maps. The countries producing coffee are very different to the countries buying it. Picture one represents coffee producers, picture two coffee drinkers.

Here are the pick of the comments from Intelligentsia buyer Geoff Watts.

“Your average coffee farmer today is making less money per pound of sold coffee than his grandparents did, in real (unadjusted) dollars, despite drastically higher living costs and production costs.”

Meanwhile, the mainstream first-world consumer has held stubbornly to the idea that coffee is a cheap luxury, that the $1.00 bottomless mug is somehow a right or a deserved privilege.

It is this very attitude that will continue to ensure that the modern smallholder coffee farmer has little hope of escaping a life of extreme poverty.

Cheap coffee (and by “cheap” I mean low cost, which typically equates to low quality) is one of the many forces shackling the developing world and suppressing opportunity for advancement for a huge chunk of the planet’s population who depend on coffee to make a living.

I would argue that even downright crappy coffee ought to carry a higher price tag than it currently does, especially considering the higher production costs that most farmers face today.”

Hands up if you’ve ever thought “opening a cafe would be fun”. This little article was just about enough for me to put my hand down to that question. Here’s a failed cafe owner elaborating on the costs of pursuing your cafe dream.

Hands up if you’ve ever thought “opening a cafe would be fun”. This little article was just about enough for me to put my hand down to that question. Here’s a failed cafe owner elaborating on the costs of pursuing your cafe dream.

“A place that seats 25 will have to employ at least two people for every shift: someone to work the front and someone for the kitchen (assuming you find a guy who will both uncomplainingly wash dishes and reliably whip up pretty crepes; if you’ve found that guy, you’re already in better shape than most NYC restaurateurs. You’re also, most likely, already in trouble with immigration services). Budgeting $15 for the payroll for every hour your charming cafe is open (let’s say 10 hours a day) relieves you of $4,500 a month. That gives you another $4,500 a month for rent and $6,300 to stock up on product. It also means that to come up with the total needed $18K of revenue per month, you will need to sell that product at an average of a 300 percent markup.”

“Coffee was a different story—thanks to the trail blazed by Starbucks, the world of coffee retail is now a rogue’s playground of jaw-dropping markups. An espresso that required about 18 cents worth of beans (and we used very good beans) was sold for $2.50 with nary an eyebrow raised on either side of the counter. A dab of milk froth or a splash of hot water transformed the drink into a macchiato or an Americano, respectively, and raised the price to $3. The house brew too cold to be sold for $1 a cup was chilled further and reborn at $2.50 a cup as iced coffee, a drink whose appeal I do not even pretend to grasp.”

“But how much of it could we sell? Discarding food as a self-canceling expense at best, the coffee needed to account for all of our profit. We needed to sell roughly $500 of it a day. This kind of money is only achievable through solid foot traffic, but, of course, our cafe was too cozy and charming to pop in for a cup to go. The average coffee-to-stay customer nursed his mocha (i.e., his $5 ticket) for upward of 30 minutes. Don’t get me started on people with laptops.”

It seems the real cost was almost to the couple’s marriage – which the writer said was saved by a “well timed bankruptcy.