This was a sermon preached at City South Presbyterian in 2024. You can listen to the podcast here, or watch it on video. Some of the block quotes were on screen and summarised but have been included in full.

What does it look like to learn to number our days? Psalm 90 is the only Psalm attributed to Moses in the Psalter; it is presented as Israel’s oldest poetic meditation on God, which may have been composed during Israel’s wilderness wanderings. It is a reflection on God’s relationship to time as an infinite being, and ours, as finite beings where every day counts.

This song carried through Israel’s entire life as a nation. These words — including a prayer — shaped how God’s people understood living in time.

“Teach us to number our days, that we may gain a heart of wisdom.” — Psalm 90:11

This is where we are turning in our series on inhabiting time and space. We have looked at how we live in spaces; how we are formed by the places we inhabit while invited to join with God in reforming or generating new patterns of life in the world; making spaces for people to come to know God. Now we are thinking about time.

We started this series in Paul’s sermon in Acts where he speaks of God making humans to inhabit space and time; our boundaries and our appointed times in history; our numbered days — so we inhabitors might search for him and find him (Acts 17:26-27).

So I wonder how you inhabit time; what your habits of time are — your routines.

Are you ruled by the clock — reacting to the passing of time, and each moment — trying to cram stuff in; meeting deadlines, rushing from one thing to another, where there never feels like enough time — the clock is ticking? Or are you a calendar person — ruled by your diary? Taking control of the way you allocate time ahead of the curve? Planning out your days, and weeks, and months and years?

Some of us might be a mix of both.

I am more a clock guy than a calendar guy — I would love to be able to use a calendar, but I am routinely flexible; chaotic; life is a series of deadlines. I am ruled by the clock — but I also waste a lot of time. I am not as productive as I could be. It is not that I am lazy. I work hard, but I am not one for life hacks; calendar hacks — counting every second.

How do you spend or fill or invest or waste your time? Are you making your time count? Or just watching it fly by?

And if God wants us to inhabit our days seeking him; finding him — how does that shape your days? The idea of this series is that this search for God is about becoming disciples; being wise builders of a life following Jesus, and how we use our time shapes who we are becoming.

Next week we will look at our weeks, and then the week after our seasons, and then how we live with the long term in view — but today we are looking at today. How to number our days; to make them count.

This is stuff philosophers love to ponder. So I want to start with a popular philosopher of time — the modern Psalmist — Jon Bon Jovi. With the lyrics from his songs I’ll Sleep When I’m Dead and It’s My Life — they are a kind of anti-Psalm 90.

Bon Jovi imagines days not counting; a week of Saturdays; no need for Sunday — for the religious day of rest — no need for resting in peace; he is here to party — not to work.

Seven days of Saturday

Is all that I need

Got no use for Sunday

‘Cause I don’t rest in peace

“I don’t need no Mondays

Or the rest of the week

I spend a lot of time in bed

But baby I don’t like to sleep, no

No Mondays or the rest of the week — time in bed, but no sleeping.

No bed, really — he will live while he is alive; he will sleep when he is dead.

Until I’m six feet under, baby

I don’t need a bed

Gonna live while I’m alive

I’ll sleep when I’m dead

There is no need for prayers; he will grasp hold of life on his terms.

This ain’t a song for the broken-hearted

No silent prayer for the faith-departed

As he says elsewhere; it is his life; it is now or never; he is not going to live forever.

It’s my life

It’s now or never

I ain’t gonna live forever

I just want to live while I’m alive

If this is the case — living while we are alive — making every moment count — that comes with its own habits that will shape the sort of person he is.

He is the foolish builder though, right? From Jesus’ story?

Because there is something else shaping a person — Bon Jovi no longer looks like this…

Now he looks like this… And one day — he will be dead.

And he will not just be dead, if the Psalm is right, and it is God who sweeps people away in the sleep of death — Bon Jovi will meet his maker.

“Yet you sweep people away in the sleep of death — they are like the new grass of the morning: in the morning it springs up new, but by evening it is dry and withered.” — Psalm 90:5-6

How do we make time count — numbering our days — in the face of death? In the face of coming face-to-face with God? Who do we want to become — not just in the face of death, but this idea of coming face-to-face with God? How does this shape how we spend today? Numbering our days. Making them count.

There is a writer I love — Tish Harrison Warren — an Anglican priest in the U.S. In her book Liturgy of the Ordinary she writes about deliberately shaping our days, our time, around seeking God, because how we spend time — whether it is a morning routine, or going to the gym, or going to work — will always function like rituals or liturgies; acts of worship that make us who we are.

“We are shaped every day, whether we know it or not, by practices — rituals and liturgies that make us who we are… we spend our days doing things — we live in routines formed by habits and practices.

How I spend this ordinary day in Christ is how I will spend my Christian life.”

— Tish Harrison Warren, Liturgy of the Ordinary

We are creatures of habit; and our routines are made up of practices, and these are what build our life.

Another writer I love — Jamie Smith — wrote this book How to Inhabit Time. He says:

“We are all choosing to synchronise our watches with someone’s configuration of time.”

We are choosing for our time to be ruled by someone — and so — who is shaping your habits of time — the shape of your days — whose schedule are you synchronising your watch to? Your own? The powers of this world? The consumer culture — the rat race — where you have to work harder and longer to produce more so you can consume more, or amass more security?

Or is it the God we meet in Psalm 90?

This Psalm makes the case that as we number our days, we ought to be synchronising our lives — our watches — to God’s rule. And when we get to Ephesians, Paul shows how our perspective changes with Jesus, and unpacks how we might live in time differently as a result; as those who have met the creator God through Jesus, and received eternal life.

Everything this Psalm says about God focuses on his relationship to time and space; his limitless experience; his mastery and power and authority — his role as Lord of all; all generations; who pre-existed the oldest things we can imagine — the mountains. God is God from everlasting to everlasting (Psalm 90:1-2). It is hard to describe infinite life poetically, but God is everlasting. While creation is not. The mountains will erode.

People are mortal — we will die and turn to dust. For God a day is a blip, a thousand years is like a day (Psalm 90:3-4). Life comes and goes — like grass — but he remains (Psalm 90:5-6).

And this produces an amount of awe — especially if God has the capacity to intervene and judge such puny finite figures as humans; to look at our sin, even the ones we think are hidden — and find us wanting (Psalm 90:7-8).

We become very small in this perspective. Our days pass away. Even our sufferings are fleeting. We might last seventy or eighty years — they pass, we fly away, we die (Psalm 90:9-10).

It is all very depressing.

We are fleeting. God is not. This is all about perspective.

And for Moses part of this picture is meant to generate a fear of God — a life that recognises him as God and so avoids his power being turned on us. A desire to learn from God to think about time, and from this perspective gain wisdom — a heart of wisdom — an understanding of reality (Psalm 90:11).

And somehow — Moses — who in the story of Exodus has come into God’s presence, who knows things about God and his compassionate, covenant love, his character — this holy, infinite, potentially unapproachably glorious and powerful God — he does not stop with fear and avoidance. He turns to God and speaks to him; he asks him for stuff; he asks him to be compassionate and to shape the days of his people, those numbering their days and recognising him as God and becoming wise.

He says “satisfy us in the morning with your unfailing love” in a way that shapes not just that one day but every day — all the days we humans are given — so that we might sing for joy and be glad even in the face of our mortality, because we are facing God instead (Psalm 90:13-14). And he is making us glad for as many days as he gives us; as many years — balancing out, or neutralising the bad, the suffering — giving people time to see and experience God’s deeds, from generation to generation (Psalm 90:15-16).

This perspective leads Moses to ask that his favour might rest on his people — so that time is not producing nothing, fleeting rubbish — but so that God, the everlasting creator, might be establishing the work of human hands; making it count; making it something wise and established and not frustrating or grass-like (Psalm 90:17).

It is a Psalm worth meditating on, and asking how the God it depicts might shape our days. Paul draws on the ideas of this Psalm in Athens as he proclaims the God who made us to inhabit time and space; the one in whom we live and breathe and have our being — and the idea that we might meet him; find him — as he reaches out from the eternal, from reality beyond our limits of space and time, into our experience of space and time in the person of Jesus so that our search for him can actually lead us to him, as he invites us into life with him. As we receive his Spirit living in us so while we live day-by-day in dying bodies, we now see our lives continuing beyond death. This has got to change how we number our days, right? Not just from Bon Jovi’s perspective, but also from Moses’ perspective.

We are now able to work towards things that last; what Jesus calls treasure in heaven. We now have a fuller sense of how to make our days count; how to be wise. We looked at a bit of Ephesians in our Before the Throne series.

The idea that we have been brought from death to life; taken out of the rule of the prince of the air — Satan — and the power of sin and death and darkness (Ephesians 2:1-2). Where all of us lived at one time, and so were headed towards death and wrath (Ephesians 2:3) — like in the Psalm. But because of God’s love for us we have been made alive with Jesus (Ephesians 2:4-5). And raised with him so that we are already seated with the God of Psalm 90, in heaven, enjoying his life — in anticipation of the coming ages (Ephesians 2:6-7). And living in this world as his handiwork, created in him to do good works; to spend our days on earth as those shaped by this reality, towards this future (Ephesians 2:10).

In Ephesians 5, Paul talks about how we become children of God who are now going to follow God’s example as we see it in Jesus (Ephesians 5:1-2). He has this phrase that I reckon should bounce around in our heads like asking God to “teach us to number our days” so we might live with wisdom. He says “be careful how you live — not as unwise, but wise” — and our English reads “making the most of every opportunity” (Ephesians 5:15-16). Literally this says “redeeming the time” because the days are evil — because life in this world is still marked by death; by those powers and principalities that lead people away from God; to folly, and the judgment Psalm 90 speaks about.

So wise people who live in time ruled by God, as those given life with God — we will number our days — make them count, knowing though our time here on this earth is limited — death is not the end of the story. And we will redeem the time; living with our position in time and space as those raised and seated with Jesus defining our days now. For Paul this looks like not finding ultimate meaning in the things of this world; the days we have here, marked as they are by evil, not being foolish, but living understanding God’s will (Ephesians 5:17).

Not filling our days with drunkenness, or sex — pursuing pleasure, now or never, living while we are alive — the Bon Jovi principle — but being filled with God’s Spirit as we speak to one another with psalms, hymns and songs (Ephesians 5:18-19). Just like Moses wanted in the Psalm.

This feels like the satisfaction Moses longed for — and Israel with him (Psalm 90:14). Making music from our hearts. And always giving thanks to God the Father in everything; always (Ephesians 5:19-20). Redeeming the time means living in this world grounded in who God is; recognising who he is; using Psalms like Psalm 90, and music, and prayers of thanksgiving to shape our hearts and our journey through time towards eternity. Not towards God, because we are already living with God. But redeeming the time; making our days count, because we are seeking to live with him.

We all synchronise our watches with someone’s configuration of time.

Bon Jovi’s?

The prince of the air?

The God of Psalm 90 who reveals himself in Jesus?

What is it for you? The Bon Jovi principle; the clock is ticking — you just want to live while you are alive. Your boss, the “clock” where you are clocking on and off. Your biological clock; stuff you want to do because you are old, or before you are old, or because death is getting closer.

What would it look like to synchronise your clock, and align your calendar — your day — to God’s plan? To number your days; to make them count — as someone living towards eternity now, by redeeming the time. Because this is what wisdom looks like. And it starts with having a plan for your ordinary days; your habits, your routines.

And how should that shape today and tomorrow as the ordinary, numbered, days that are the building block for your Christian life? How will you make them count? Redeem the time? Sync up with God? We have been thinking about habits we might adopt in space; about practicing the way of Jesus — doing what he calls us to.

Building our lives wisely by building them on his life; on his teaching (Matthew 7:24). On imitating his example, and the example of those who imitate him (1 Corinthians 4:16-17). Creating a way of life (1 Corinthians 4:17). We have talked about the idea of a ‘rule of life’ while exploring Practicing the Way together, this ‘rule’ is a deliberate pattern we might adopt in our lives to give them a structure so we are growing towards where God wants us to be growing towards; a way to “schedule our daily life practices and relational rhythms that align our time and our habits to our desire to be with Jesus and become like him,” to be wise.

James K.A Smith reckons part of this wisdom is captured in the spirit of Psalm 90; recognising that our lives in the flesh are transitory; that we are limited in ways God is not; that we need to learn to keep time.

“Learning to live with, even celebrate, the transitory is a mark of Christian timekeeping; a way of settling into our creaturehood and resting in our mortality….”

As we settle into our creaturehood and rest in our mortality — not live the unsettled, hurried, life of Bon Jovi, trying to cram everything in, get all we want…

But learn to be content in time — temporal contentment; inhabiting time with eyes open, hands outstretched, not to grasp and make the most of every moment on our terms, but to receive and enjoy and let go. To practice thanksgiving and rest in who God is.

“This is temporal contentment: to inhabit time with eyes wide open, hands outstretched, not to grasp but to receive, enjoy, and let go.” — Smith, How To Inhabit Time

It is his life. And he gives us now and ever. So what does this look like day-to-day; redeeming the time — living in our limits, wisely — but also towards eternity?

When it comes to how we spend our days — most of us will spend our days working in some form of labour — whether it is paid, or unpaid; out, or in the home — grandparent duties or in the trenches of parenting — and this work can feel meaningless if our life feels like it is being wasted and going nowhere.

Some part of redeeming the time will mean asking, with the Psalmist, that God will establish the work of our hands; directing them and giving us a sense we are approaching work with purpose.

The purpose of doing good; bringing order; orienting our hearts and our bodies towards heaven as we do the good works God has prepared in advance for us to do.

Redeeming the time at work might involve prayerfully orienting your labour towards this greater meaning; seeking to work as though working for the Lord. Not simply sharing life and love and hope with, or praying for, your colleagues — though those are good habits to get into — but by working with eternity in mind. Sometimes that just means remembering that some of what we do feels pointless and mundane, and fleeting, but we might be building character that lasts forever, and we might find ways to enjoy the fruits of our labour and the satisfaction of a job well done.

Our best work though will be limited; we are not omnipotent creatures of boundless energy. Our work comes from a place of rest — we are maybe addicted to busyness and productivity as a culture, but part of numbering our days and remembering that God is infinite while we are finite and limited is scheduling rest. This will be part of how we think of the week next week — but it is also part of how we think of the day — sleep.

Now. Sleep is harder to come by for some of us — because of our bodies or our brains or our circumstances — and I do not want to be insensitive to that struggle. But those people will tell you that sleep is a good gift from God, even if it feels unattainable. And I know for myself, and for others, that sleep sometimes feels like not living.

Like Bon Jovi we might feel like sleep is a waste of time; something we do not like because it gets in the way of partying.

That we will sleep when we are dead.

But rest — it is one of the good gifts of God Jesus came to give us — and our days are not just made for work, but for play — recreation — relationship — and rest, and sleep (Matthew 11:28-29).

“Come to me, all you who are weary and burdened, and I will give you rest. Take my yoke upon you and learn from me, for I am gentle and humble in heart, and you will find rest for your souls.”

And redeeming the time, numbering our days; recognising that we are finite and that we depend fully on God, not ourselves — might require trying to, at least, sleep.

We are able to sleep — so the Psalms say — because God does not sleep; he looks over us as we slumber; he does not sleep so that we can. So that we can rest in him while embracing our limits. But this might also mean working less. Being less busy; less productive.

“He will not let your foot slip — he who watches over you will not slumber; indeed, he who watches over Israel will neither slumber nor sleep.” — Psalm 121:3-4

Maybe the best thing you could do to redeem the time is learn to slow down; to rest; to sleep — to let go and let God, so to speak. To un-hurry, as John Mark Comer who is behind Practicing the Way puts it. He reckons many of us will be too busy to add Jesus to our daily schedules; too hurried; not resting; not making space in our lives. We fill our lives — Bon Jovi style — with the sort of stuff Paul tells us not to do, and crowd out the life-giving stuff we ought to do, including rest.

“The elephant in the room is that the vast majority of us have far too much going on to ‘add’ Jesus into our overly busy schedules.” — John Mark Comer

And our best work, and rest; our best redeeming of the time; our best numbering of our days begins with knowing who God is, and who we are before him; creatures — not the creator — those who live before the throne of God in heaven, which shapes us for life on earth. Redeeming the time might mean spending time located in not just our future home, but a home we are located in now, by God’s Spirit. As we sing Psalms, and songs, and always give thanks — praying — not just sometimes (Colossians 3). Did you notice as we looked at Acts 2 earlier in the series the early church met daily together (Acts 2:46-47); involved in these rhythms?

They met habitually — with the idea this habit would increase the more they understood how life now is oriented towards life eternal; that day approaching (Hebrews 10:25). They just could not get enough of time together, or time with God.

I wonder if that sort of time with God — before we think about time with others — is part of our days. Did you notice in Psalm 90 Moses calls out to God asking that he might satisfy us in the morning so our days might be filled with his love; that we might sing for joy and be glad all our days (Psalm 90:14)?

There is lots of stuff in the Psalms that aligns with the practices we see Jesus and his disciples embracing through the Gospels — probably because the Psalms are their songbook. They seem to routinely pray at certain hours of the day.

One suggestion is that this is a tradition that begins in Psalm 119, which is all about meditating on God’s word — a life filled and formed by the Scriptures — where the Psalmist says “seven times a day I praise you…” (Psalm 119:164).

What would your calendar look like if you had reminders in it to pray seven times a day? What about just one? Or two? This is how we redeem the time.

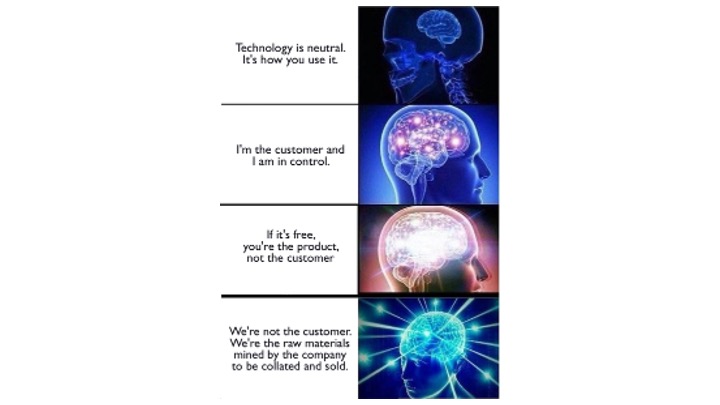

Now look — for most of us our calendars and clocks are on our smart phones. And we probably have habitual relationships — some might call them addictions — to these little devices; rituals training us not to redeem the time, or rest, but to waste it.

I am not sure the answer is to get a dumb phone, or no phone — but I wonder if we might use our phones as tools to help us redeem the time; to shape our hours, to remember to pray, and even to provide us words to pray when we cannot come up with our own.

Some of us really like the project Every Moment Holy, which is a group of creative folks committed to writing beautiful prayers for all sorts of moments that come up in modern life; whether these are hard or special occasions, or just the mundane day-to-day stuff. You could get a hold of that app, or go old media and get a hold of the books.

Maybe you could set a reminder, or create a habit of Bible reading, prayer, and journaling with leather-bound tactile books that break the phone’s hold on you. Or maybe you could get an app like PrayerMate, that helps you track prayer points and pray for the people you promise to, and prompts you to do it throughout the day. You might redeem the time by using your phone to dig into the Bible — whether just in a Bible app, or something like the Bible Project, which I love. I have even got a life hack where I will listen to Bible Project podcasts, other great podcasts, or Christian audiobooks while I am gaming. Talk about redeeming the time!

Whatever you do as we work towards a rule of life; however you structure your numbered days — what would it look like to redeem just a little bit more of the time by adding just one or two more practices, could be from this list, could be something else, so that you are deliberately pursuing wisdom and embracing reality; the reality of who God is and who you are.

A wise life inhabiting time as people who are going to die, and face our maker is a life grounded in Jesus; a life looking towards eternity; a life redeeming the time we have now as we do the good works God has prepared for us — as those who know God because we spend time with him.

Are we going to take advice for how we fill our time from Jon Bon Jovi, or from Jesus?