This was a sermon preached at City South Presbyterian in 2024. You can listen to the podcast here, or watch it on video. Some of the block quotes were on screen and summarised but have been included in full.

I have a rule with preaching that I do not do sports illustrations.

It is not because I do not love sports. I love sports — but I am aware others do not like sports; or sports illustrations. They are alienating. I am making an exception because I do like weird DIY graphs, and this fits this chapter’s theme — we looked at inhabiting space, and then have spent the last couple of chapters thinking about numbering our days and redeeming the time and the shape of our week — this chapter is about seasons. And you know what has seasons… sports.

At the time I preached this sermon, I had just finished playing a season of over 35s football — soccer for uncultured folks — I am the goalkeeper. In the 2024 season we did not make the finals, so it was all over (in 2025, at the time of posting — we had made the finals, and won the Grand Final).

The team I play for started playing together in the Baptist league; some of us have played together for 15 years — since our 20s, playing against 40 year olds, and then found ourselves in our 40s playing 20 year olds, so we moved to a more age-appropriate league where we are in our prime again, not past it. Now — you have been waiting for the graph I flagged above.

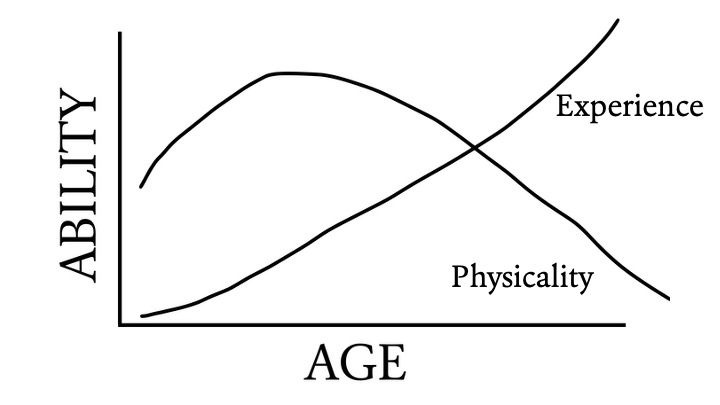

Here is how life works if you play sport. At some point you hit your peak. You are the best you will ever be.

When you are young you are fit and healthy; you might move better, but as you gain experience, you play smarter — and at some point, it all clicks and you hit your peak — the perfect overlap of experience and ability — a real sweet spot. Life before this moment is prep for that season, and from then on, you are always kinda trading on the glory days.

I think I peaked in 2010 — at 27 — here I am lying on the ground in the grand final.

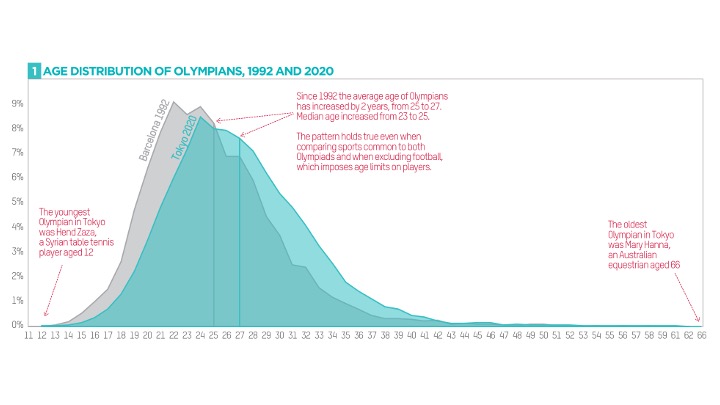

Turns out my graph is based in reality — this journal article looks at average ages of success in different high-level sports in Australia.

First — the good news for people considering a run at the 2032 Olympics — Olympic athletes are getting older on average — there was a 66-year-old competing for Australia in Tokyo.

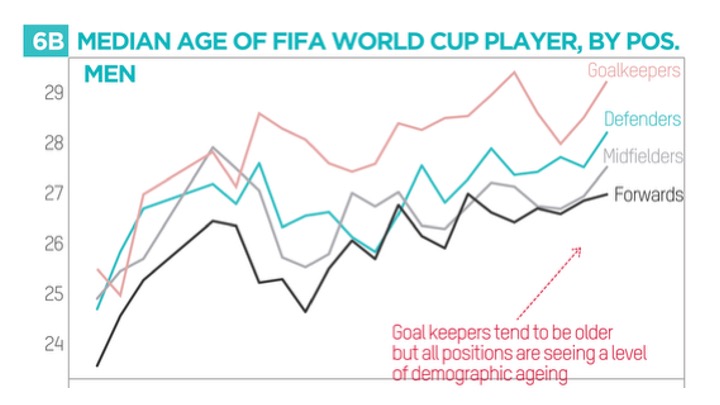

They also looked at male World Cup footballers, concluding attackers peak at 25, defenders at 27, mids in the middle, and goalkeepers are the oldest player type — where our agility and reaction time might decline, we learn resilience and strategic decision-making, and mostly we are just tall.

“Goalkeeping requires significant agility and reaction time. Traits benefiting older players, such as psychological resilience and strategic decision-making, are also important. These skills are thought to develop with experience and age… Their greater playing longevity may be because they are specialized both in skill and body type: they are often taller.”

This sounds a bit right. My body is slowing down every season; my recovery time is longer — but I am probably playing smarter.

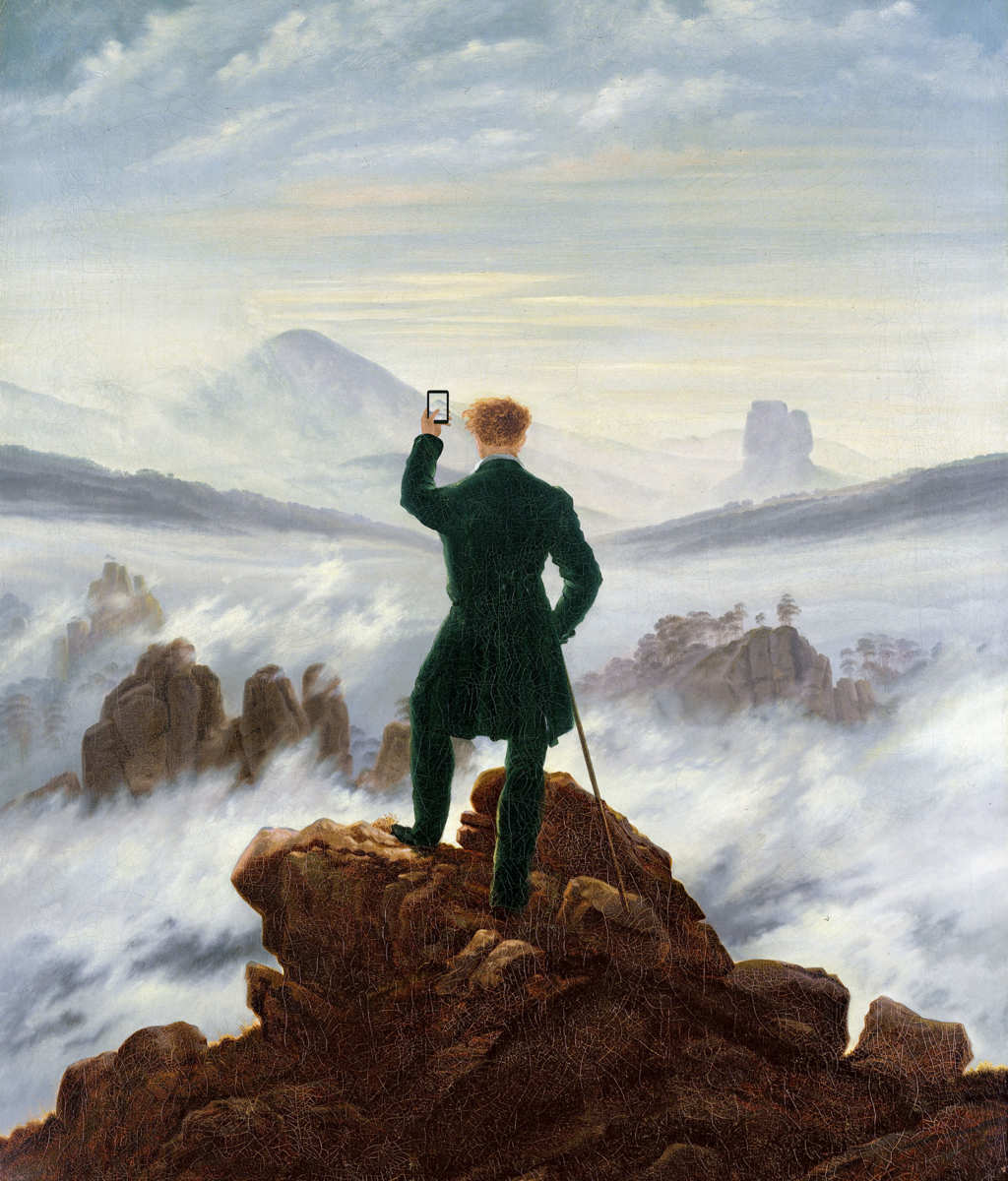

What is true of sport is true of many parts of life — this is why sporting illustrations are preaching gold. This season stuff is true of discipleship too. Becoming more like Jesus — our habits and practices will look different in different seasons of life — our capacity will vary, but there are ways our experience teaches us to be smarter.

Discerning the changing of seasons and how this changes what we are called to do within our limits is vital to redeeming the time. This sort of discernment is important for our own growth and for the role we play in the household of God.

So. What season of life are you in? What does living wisely — building wisely by practicing the way of Jesus — look like in this season with your mix of experience and strength and energy and availability and ability? Especially where you maybe cannot jump at tasks you might have in earlier seasons, but where you have developed some other skills — or maybe you are just tall.

Our lives will be made up of various seasons; you have got your classics — birth, childhood, adolescence, young adulthood, adulthood, middle age, old age, dying — and then sorts of shifts that happen along that continuum — education, getting a job, leaving home, maybe marriage, maybe kids, maybe job loss, maybe buying a home, maybe renting, maybe grieving relationship breakdown, or singleness, or childlessness, maybe job transitions, raising teens, maybe caring for an elderly parent, grandparenting, grieving dying parents, grieving lost children, a medical diagnosis — every one of these is not just an ‘event’ where it just happens in a moment and is gone; these are experiences that stretch over a body of time, often overlapping.

And if we pretend they do not change our capacity — or what faithfulness and wisdom look like in our lives — we are kinda missing part of what it means to inhabit time faithfully while seeking God; seeking to become godly in the circumstances where he has placed us.

Part of maturity is not just knowing who I am and acting with integrity — it is — as Jamie Smith puts it in How to Inhabit Time — being able to answer the question “When am I?”

He reckons seasons are a better way to discern when we are and how we should live than days and dates… that if we discern what season we are in, this helps us know what to expect, and that the key to living well through these seasons is not numbering our days by the sun, but by remembering that in every season, we revolve around the Son.

“The answer to the question ‘When am I?’ is not six o’clock or 2022; it is more like youth, middle age, chapter 3 of a life… To ask ‘When are we?’ is not a question of counting years as much as discerning a season, knowing what to expect… Remembering that, in every season, we revolve around the Son.”

Somehow that pun is less clichéd when you have as much panache as Smith.

This discernment of the seasons helps us see that our situations are temporary; to receive the good and live through the bad… which is the tension the poem in chapter 3 of the book of Ecclesiastes explores; it is an invitation to discern the time — the season — and act appropriately.

The poem opens declaring there is a time and a season for everything — and then it describes a bunch of times — seasons — where different actions are appropriate — as well as milestone moments — birth and death, planting and uprooting, killing and healing, tearing down and building.

Some people might say deconstruction and construction here. Some of us have experienced these sorts of seasons in our lives, our faith, our relationships. In any of these, if you do the wrong thing, that is bad, right? We had some ‘help’ from some folks in the garden out the back where we uprooted when we should have been tending to the plants, and it set the garden back a bit.

A time to weep and a time to laugh, to mourn or dance, to scatter or gather, to embrace or refrain, to search and to give up, to keep or throw away, to tear or mend, to be silent or speak, love and hate, war and peace — lots of these are momentary, but some of them are seasons (Ecclesiastes 3:1–7) — and wisdom lies in discerning the difference and acting according to the time.

This list — they are all actions where we have agency to respond to the situation or season or time we find ourselves in — and maybe one of the things this poem also invites us to see is that if we are always just doing one of these options — always uprooting or deconstructing and never moving into a different season — then we might be stuck in a less than wise rut. We are made to discern the time and to act in ways that go somewhere.

Although, the writer of Ecclesiastes is maybe not sure there is anywhere to go, because our seasons end. Eventually.

We worked through the book of Ecclesiastes as a church when we were looking at the books that are often called Wisdom Literature; we saw how it tells the story of someone — a teacher — who we are meant to identify as King Solomon searching for meaning under the heavens (Ecclesiastes 1:12–13); specifically, under the sun — which is a phrase that mostly seems to be about life on earth without much reference to God (Ecclesiastes 1:13–14). In Genesis it is the heavenly lights that shape how we measure the passing of time on earth (Genesis 1:14).

Solomon is trying to make sense of life if death is the end of the story — if every moment is fleeting — this Hebrew word hevel that gets translated as “meaningless” (Ecclesiastes 1:13–14), but is more literally the word “breath” — if every moment, every season, is temporary.

The whole book is an extended meditation on the burden the teacher describes after his poem (Ecclesiastes 3:10) as “the burden God has laid on the human race.”

The burden is this idea that everything is beautiful in its time, but that time seems so fleeting in the face of eternity — and our longing for something lasting — that sits beside knowing our fate; knowing one day the breath will leave our bodies; one breath will be our last. Fleeting. Meaningless. Breath (Ecclesiastes 3:11).

In this he reckons we are no different to the animals… the same fate awaits us all; the same breath animates our bodies. Everything is breath. Temporary (Ecclesiastes 3:18–19).

The teacher’s advice is to embrace the moment; discern the time — the season — and roll with it; eat, drink, be merry — work hard and enjoy our labour — know that whatever season you are in, good or bad, it will pass — and that life is a series of different times and experiences and moments (Ecclesiastes 3:12–13).

There is some wisdom here, right? When it comes to not trying to make fleeting things eternal. We can waste a lot of time and money trying to be eternally young and never die. We can look for magical ‘forever young’ solutions; trying to hold on to a magic season and never experience the maturity and wisdom that comes through navigating our way through other seasons.

There is wisdom in discerning what season we are in under the heavens (Ecclesiastes 3:1), and how to live accordingly — in knowing when to move to over-35s, or walking football, or coaching rather than trying to keep up with 20-year-olds.

The teacher in Ecclesiastes does not have the same perspective Paul offers in 1 Corinthians — where Paul says, “Actually, the resurrection of Jesus and our resurrection with him is a game changer for how we live in time.” It is not that we should not discern the seasons still, but picking a wise reaction to each season includes hopeful certainty about where we are going.

He also uses a bit of seasonal language — farming language — through this passage, as he describes the resurrection of Jesus as the first fruits (1 Corinthians 15:20); the beginning of a new season — the start of something new even for those who have died already.

It is fun reading this bit of 1 Corinthians and its wisdom side by side with Ecclesiastes. The teacher says “humans and animals have the same breath of life” — which is a reflection on Genesis 1 and 2 — and death makes everything “breath” — fleeting. Paul is like, “Yep. Without the resurrection of Jesus, this is true — even faith is futile” (Ecclesiastes 3:19; 1 Corinthians 15:17).

If he is not raised and we are not raised, then the teacher’s wisdom is right — eat, drink, and be merry, because tomorrow we die (Ecclesiastes 3:13; 1 Corinthians 15:32).

But there is a game changer — our dying “under the sun” bodies are not the end of the story. Living in dying bodies still requires wisdom and discerning seasons of time and what these perishable bodies are capable of — but because of the resurrection of Jesus, these dying bodies of breath are not the end of the story (1 Corinthians 15:42–43).

Our natural bodies will be replaced with spiritual bodies (1 Corinthians 15:44). There is a fun thing in the Greek here where Paul is playing with two different words that can be translated as “breath” and “spirit.” What we get as “natural” uses the same Greek word the Greek translation of the Old Testament uses for the breath of life — the fleeting breath that animates even the animals but disappears on death. And the resurrection body — Paul uses the word pneuma — or spirit — here, the word used for the Holy Spirit. Jesus’ resurrection breath being given to our bodies changes the story.

Now we do have something the animals do not. We had the same breath; now we are animated by God’s Holy Spirit (Ecclesiastes 3:19; 1 Corinthians 15:44).

Now not everything is meaningless… breath. Fleeting. Ending in death. Our destiny has changed; our season has changed; our burden has been lifted. Now we are living — as those with the Spirit — in anticipation of an entirely different season with an entirely different body; one that will not break down and decay, while our experience grows.

I do not know if this graph is entirely accurate — I do not know if our heavenly, imperishable, glorious bodies will be 27, or improve over time — but we will not be experiencing the frustration that comes from dying and decaying bodies that break down and recover slower.

One day the perishable will be clothed with the imperishable — the mortal with immortality (1 Corinthians 15:54). We will see continuity in the bits of our lives that we have invested in the spiritual reality, the life of Jesus — and the other bits will be left in the grave and defeated.

And this future hope might inform how we navigate seasons of frustration and change now — or even great seasons of joy and productivity where we might be inclined to forget eternity and try to make these fleeting moments last forever.

Paul says through Jesus and his resurrection we are liberated from the worst aspects of time — death — as we are also liberated from sin and the law that condemns us. We have this victory through Jesus (1 Corinthians 15:56–57). That is what you want at the end of a good season.

And so this shapes every moment.

Paul says we ought to stand firm — no matter the season we are in — not be moved from this truth that shapes our days and our seasons and our lives. Always — through every season — giving ourselves fully to the work of the Lord (1 Corinthians 15:58).

That will change season by season, in accordance with our obligations and our limitations and our health and our energy and our strength — but when we are labouring in the Lord it is not meaningless; it is not vanity; it is not just breath — it is not just under the sun (Ecclesiastes 1:13–14).

It is for eternity — an eternity enjoying the fruits of this work for God as he sets the table for us to eat, drink, and be merry under the Son.

This is God’s answer to the longing for eternity set in our hearts. It helps us receive beautiful seasons and moments now as temporary pictures of what is to come, and the ugliness — especially the ugliness of dying — breaking down to dust — as temporary struggles and sorrows that will also pass and can be endured.

So how do we do this? What are some practices we can embrace to live seasonally; to rightly number our days, asking “When am I?” discerning the time so we can redeem it and live wisely?

Some of us are in our physical prime — we have so much energy and motivation; we are not weighed down by some of the commitments that come with family — whether with a spouse and kids, or ageing parents who need care — we might lack some experience and wisdom, but that will come with practice. Stewarding this season might mean stepping up and saying yes to challenging things, recognising that you have this season as a gift, and that it is fleeting. This might play out at work or at home or here at church. I am thankful for the way so many younger adults without kids serve our community with energy and enthusiasm — especially those who are teaching kids in kids church to help parents navigate this season.

This season for you might involve grief about unrealised hopes, or navigating the path to get to a new season. This requires discernment, recognising limits — our humanity — maybe even confronting the way our bodies are imperfect and limited no matter how hard we push them. That is okay. There are practices you can embrace in this season that will grow you towards your eternal future. You might look around and resent some older folks because of how much you are doing and forget that older folks have been through that season, have done the stuff you are doing now — and might wish to still be doing it… but they… we… just cannot.

Many of us are past our physical prime. It is true. We are in dying bodies that do not have the energy we once had. How do we live faithfully with the time we have left — valuing our experience? Maybe there is a set of habits or practices you might embrace that are the discipleship equivalents of walking football or coaching; slowing down — still doing the stuff you loved, but as someone who brings experience but not speed to the field, or helping from the sidelines; energising and encouraging. Maybe there is stuff you imagine that you cannot do anymore because you cannot do what you used to — but maybe you are like a goalkeeper and you might find you have got more useful with age, and wasting energy is not the wisest path.

I have got to say — I do not just love that young adults are involved in our kids ministry — you might not have noticed, but our elders are rostered on creche or kids church most weeks. You might join them. Your knees might not cope with playing on the carpet, but you can take a chair and offer love to our kids — or find ways to help parents in our church navigate this season, or offer support and encouragement to single folks navigating a complex season filled with griefs and hopes and challenges to stay godly that look different for each of us.

This discernment — it is not a solo sport. It is part of living in the household of God (1 Timothy 3:14–15); part of being family for each other — the environment in which we each grow and learn and navigate seasons with those who have gone before and those coming after us.

Discernment requires listening — perhaps to those who have gone before — not because being old automatically brings maturity, but because navigating seasons with wisdom that produces godliness is actually what maturing might look like. I know as a younger person I was dismissive of older folks, because what would they know — and I still can be — but now as an older person I am realising that some of what I offer is maturity, not just old-person thinking, and some of what younger people — not exclusively my own children — lack is hard-won maturity, where some of that winning happens through struggle, but maybe some of it is easier to navigate with a good coach.

Those of us who are younger might need to cultivate a practice — and the sorts of relationships — where we can listen to older, more mature voices, while those of us who are older might need to realise what we have to offer; discerning what is mature and what is appropriate for any given season of life — not just cultivating an expectation that young folks will act just like us. That is not wise either. Wisdom is about acting according to our season.

Smith talks about this as a bit like time travel, where the church is like a time machine; as older, wiser folks who have negotiated a season can report futures those navigating a season cannot comprehend — creating hope. He says:

“Trading testimonies across generations turns the communion of saints into a time machine… When an older friend reports from a future you could not imagine, your imagination is infused with a new possibility. That is called hope.”

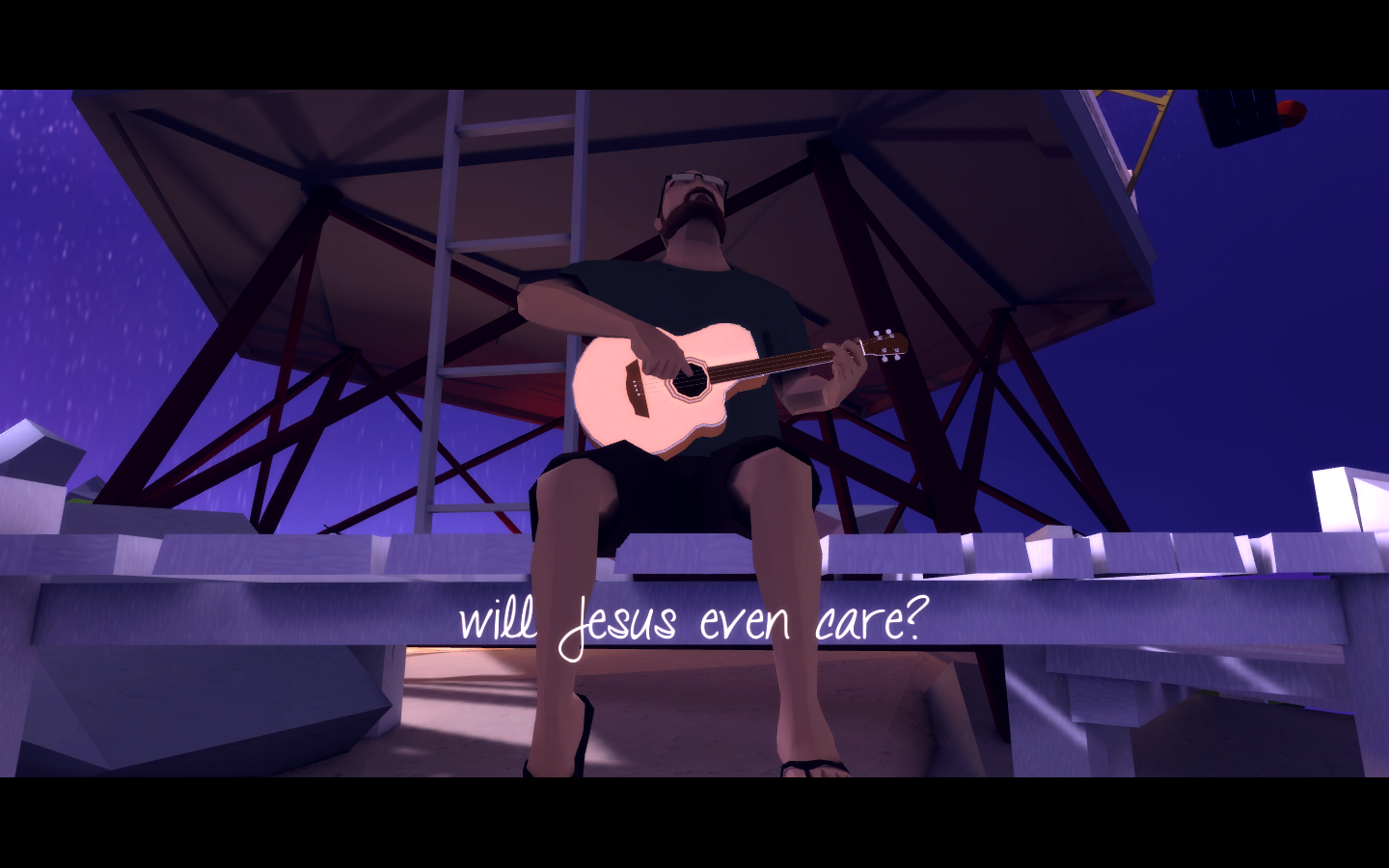

Some of us are entering — or in — the final season. And this season presents its own particular moments; fleeting moments that might not come back and might be savoured or grieved with particular weight. It is not easy for a young bloke like me only just past sporting retirement age to speak about this — but this is a season some of you are facing. A season not of firsts but of lasts, or “maybe lasts,” where you are just not sure.

And we want to honour that as your church family; to walk with you, to laugh with you, to cry with you, and to be there through this time — as you work out how to say goodbye; how to finish well — and as you model that to us too — especially how to finish well — to mourn while hoping.

We want to see you live as though life is not meaningless but death has been swallowed up in victory, and we want to play our part in celebrating and reminding you of that while thanking God for the seasons you have experienced. Because one day, whether we know it or not, we each experience this season.

The call for each of us — in each season — is the same; according to our ability and capacity and experience — it is to not be moved from our hope; to stand firm in Jesus and give ourselves fully to the work of the Lord. To live for him. To live shaped by the way he shapes time.

One way Smith reckons churches can do this is to think differently about time — to see time as cyclical, not linear. There is an ancient practice where church communities have structured their years to rehearse and remember the Christian story — the church calendar — holy days — they still mark our secular calendar with Christmas and Easter — but this is a way to remember that time does not revolve around the sun but the Son; and that we do not live under the sun but under the Son. He is our centre of gravity.

In this calendar each year begins with a deliberate movement towards the events of Gethsemane and the cross — the silence of Easter Saturday and the explosion of light from the rising Son.

“The Christian inhabits time as cyclical and linear… The liturgical calendar rehearses the way time curves and bends around the incarnate Christ like a temporal center of gravity. Every year, the church walks with Jesus toward Gethsemane, bears witness to his anguish and suffering, steps again into the chilled shadow of the cross, lives with the harrowing silence of Holy Saturday, and arrives on Easter morning to witness the explosion of light that is the resurrection of the Son of God.”

And we end the calendar with Advent, anticipating, hoping for the coming of the Messiah, remembering that he has come — in flesh — stepping into time in a way that changes everything. Embracing this cycle — these annual seasons — we remind ourselves of our story in every season of our own life.

This is already something we have started to do more of together as we gather as a church, but marking time this way in your homes might be something you consider as we cultivate a rule of life together and navigate each season that life throws at us.

We are all caught up in the business of learning to tell the time; to discern the season we are in so that whenever we are in life, we can give ourselves fully to the work of the Lord, because when we labour in him — eyes and hearts towards eternity — it is not in vain.

Why generous pluralism is a better ideal than idealistic purism and provides a better future for our broad church (or why I resigned from GIST)

This week I resigned from a committee I’d been on since 2011, I was at the time of resigning, the longest serving current member. I resigned because I did not and could not agree with the statement the committee issued on the same sex marriage postal survey, and I wanted to freely and in good faith publicly say why I think it is wrong, and to stand by my previously published stance on the plebiscite.

In short, I did not think the committee’s paper fulfilled either aspects of its charter — it is not ‘Gospel-hearted apologetics’ in that there is nothing in it that engages particularly well with the world beyond the church in such a way that a case for marriage as Christians understand it might convince our neighbours of the goodness of marriage, or the goodness of Jesus who fulfils marriage in a particular way; nor do I believe it effectively equipped believers to live faithfully for Jesus in a secular society; instead, it equipped believers who were already going to vote a particular way to keep voting that way and to have some Gospel-centred reasoning to do so. I’m not convinced the way it encourages people to vote or speak about that vote, or understand the situation grapples well with our secular context; as someone not committed to a no vote already, I found the paper unpersuasive even after a significant review process.

But there was also a deeper reason for my resignation (resigning over just one paper would not be a sensible course of action) — this paper reflects a particular approach to political engagement in a fractured and complicated world that I do not support, and there was no evidence the committee would adopt an alternative strategy. I resigned because the committee failed to practice the generous pluralism that I believe the church should be practicing inside and outside our communities (on issues that aren’t matters of doctrine — there’s a difference between polytheism and pluralism). I had asked for our committee to put forward the views of each member of the committee rather than the majority, because the committee’s remit is to ‘equip believers in our churches to engage in Gospel-hearted apologetics’ and ‘to live faithfully for Jesus in a secular society’ — and I believe part of that is equipping believers to operate as generously as possible with people we disagree with in these complicated times.

The statement issued by the committee is no Nashville Statement; it is an attempt to be generous to those we disagree with, without offering a solution to a disagreement that accommodates all parties (or even as many parties as imaginable); it is also an idealistic document, and so as it seeks to push for an ideal outcome it represents a failure to listen and engage well with other people who hold other views — be they in our churches, or in the community at large. It is this failure to listen that led me to believe my energy would be better spent elsewhere, but also that leads me to so strongly disagree with the paper that I am publishing this piece.

This is not, I believe, the way forward for the church in a complicated and contested secular world; it will damage our witness and it represents the same spirit to push towards an ideal ‘black and white’ solution in a world that is increasingly complicated. I’m proud of this same committee’s nuanced work on sexuality and gender elsewhere, and don’t believe this paper reflects the same careful listening engagement with the world beyond the church and the desires of the people we are engaging with (and how those desires might be more fulfilled in knowing the love of Jesus). By not understanding these desires (not listening) our speech will not be heard but dismissed. This paper is meant to serve an internal purpose for members of our churches (so to persuade people to vote no), but it is also published externally on our website without any clarification that it is not to be read as an example of Gospel centered apologetics, so one must conclude if one reads it online, that this is a paper that serves both purposes of the committee.

I’m not the only voice speaking out in favour of pluralism, nor am I claiming to be its smartest or best spokesperson. John Inazu’s book Confident Pluralism and his interview in Cardus’ Comment magazine gave me a language to describe what I believe is not just the best but the only real way forward in what Charles Taylor calls our ‘secular age’ — where the public square is a contested space accommodating many religious and non religious views. If we want to resist the harder form of secularism which seeks to exclude all religious views from the public square, it seems to me that we either need a monotheistic theocracy (but whose?) or a pluralistic democracy that accommodates as many views as possible or acceptable; and this requires a certain amount of imagination and a sacrifice of idealism. The thing is, for many of us who’ve been brought up in an environment that defaults to the hard secular where the sexual revolution is assumed (ie anyone under about 38, or those who are a bit older but did degrees in the social sciences), we’ve already, generally, had to contest for our beliefs and adopt something like a pluralism. There are ways to prevent pluralism — like home schooling or insularly focused Christian education, but if people have grown up in a ‘public’ not stewarded by a particular stream of Christianity that deliberately excludes listening to the world, or if they are not particularly combative and idealistic types who have played the culture wars game from early in their childhood, then they are likely to have adopted something that looks pluralistic.

Here’s a quote from John Inazu’s interview with James K.A Smith, from Comment:

But it’s also not just Inazu who has spoken of pluralism; it’s also John Stackhouse in a recent piece for the ABC Religion and Ethics portal. In a piece titled Christians and Politics: Getting Beyond ‘All’ or ‘Nothing’, Stackhouse says:

Now, it’s interesting to me, particularly in the process that led to my resignation from the committee to consider how the dynamic between these three camps plays out within Christian community (it’s also interesting to consider how these three categories mesh with three I suggested using the metaphor of hands — clean hands, dirty hands, and busy hands in a post a while back); I’ll go out on a limb here and say idealism is always partisan, and so we need to be extremely careful when speaking as an institutional church if we choose to pursue idealism in the secular political sphere (especially on issues of conscience where there are arguably many possible faithful ways to respond to a situation with an imagination that rejects the status quo served up to us by others); while pluralism is the way to maintain clean hands as an institution in that model.

The idealistic stream of Christianity will see the pluralist as not just compromising politically but theologically, because while the pluralist will be operating with perhaps something like a retrieval ethic, the idealist will operate with something more like a creational ethic or a deontological ethic or a divine command ethic and so see their path as clearly the right way, and thus other paths as wrong. The pragmatist will have sympathies in both directions, and the pluralist will seek to accommodate all these views so long as they still recognise the truth the idealists want to uphold (if they don’t they’ve become ‘polytheists’). I predict the church, generally (and specifically in our denominational context) will face a certain amount of problems if not be damaged beyond repair if we put idealists in charge and they tolerate pragmatists but exclude pluralists — especially if those who have grown up needing to be pluralists to hold their faith. A push to idealism rather than confident, or generous, pluralism, will alienate the younger members of our church who are typically not yet in leadership (and this dynamic has played out in the Nashville Statement), and it will ultimately lead to something like the Benedict Option, a withdrawal from the pluralistic public square into our own parallel institutions and private ‘public’.

It’s interesting to me that GIST fought so hard against withdrawing from the Marriage Act, because, in part, the government recognises marriage contracts entered into by the parties getting married and conducted by a recognised celebrant according to our marriage rites — so there is already a difference between how we view marriage and how the state does — pluralism — but has now reverted to arguing that the government doesn’t just recognise marriage according to a broader definition than we hold but promotes and affirms particular types according to a particular definition. I know that was our argument because it was the one I spoke to in the discussion at our General Assembly.

Here’s my last smarter person that me making the case for pluralism in these times, New York Times columnist David Brooks in his review of the Benedict Option. He opens by describing two types of Christians not three — and Stackhouse’s pragmatist and pluralist categories fall into the ‘ironist’ category.

If the purists run the show we’re going to end up with a very pure church that ultimately excludes most impure people ever feeling loved enough, or understood enough, to bother listening to what we have to say. Purists are necessary though to keep us from polytheism or losing the ideals. Here’s more from Brooks:

Brooks uses ‘Orthodox’ to qualify pluralism, Inazu ‘Confident’; I’ve settled on ‘generous’ (see my review of the Benedict Option for why).

If our denomination puts the idealists/purists in power without an ethos of including the pluralists (a functional pluralism) they will always by definition exclude the pluralists; whereas if we adopt a pluralistic approach to the public square (and to how we give voice to those who disagree with us within the camp of orthodoxy) then we will necessarily also give space to the pluralists. The choice we are faced with is a choice between a broad church and a narrow one. What’s interesting is that pluralism actually becomes an ideal in itself; one of the reasons I resigned is that I am fundamentally an idealist about pluralism, once it became clear this would not be our posture or strategy, I could no longer participate (because I was excluded, but also because I am an idealist and saw the purist-idealism as an uncompromising error).

So this is a relatively long preamble to establish why I think the position adopted by GIST (idealism/purism) and how it was resolved within the committee (idealism/purism/no pluralism) is deeply problematic and a strategic misfire in our bid to engage the world with ‘gospel hearted apologetics’.

Generous pluralism and ‘living faithfully for Jesus in a secular society’ and ‘engaging in gospel-hearted apologetics’ in a polytheistic world

GIST’s philosophy of ministry acknowledges that we live in a ‘secular society’ but maintain some sort of difference from that society by ‘living faithfully for Jesus’. The idealism that Stackhouse speaks of, or purism that Brooks speaks of, will fail if society is truly secular.

Idealism will fail us because at the heart of idealism is not simply a commitment to monotheism as the option we faithfully choose amongst many contested options in the broader public, but as the option the broader public should also choose as the temporal best (following Stackhouse’s definitions). So we get, in the GIST statement, sentences like, which holds out a sort of ideal around marriage (rather than a ‘faithful life’ within a secular society):

It seems unlikely to me that this ideal of society returning wholeheartedly to God’s design for marriage (essentially a Christian society) is possible this side of the return of Jesus (which is why I’m a pluralist), and I am confused about this being an ideal that we are to pursue as Christians.

Here’s why. I think this sort of wholehearted pursuit of God’s design for marriage was an ideal in Israel (but the sense that the ideal is not actually possible is found in God’s accommodation of divorce in the law of Moses, though he hates it and it falls short of the lifelong one flesh union). I think this ultimately is a form of the pursuit of monotheism for all in society; a noble ideal formed by an eschatology where every knee will one day bow to Jesus (Philippians 2). Israel was to pursue a sort of societal monotheism — this is why they were commanded to destroy all idols and idolatrous alters — utterly — when coming into the land (Deuteronomy 4-7) and to keep themselves from idols. There is no place for polytheism — or idolatry — within the people of God (and yet the divorce laws recognise there is a place for ‘non-ideal’ broken relationships and dealing with sin to retrieve certain good outcomes). Israel was to be monotheistic and to guard the boundaries of monotheism within its civic laws. We aren’t in Israel any more — but the church is the kingdom of God, and we as worshippers of Jesus are called to monotheism in how we approach life, this is why I believe it’s important that the church upholds God’s good design for marriage in a contested public square as part of our faithful witness to God’s goodness.

Now, while an Israelite was to destroy idols when coming into the land, and Christians are to ‘keep ourselves from idols’, outside of Israel our monotheism as Christians manifests itself in the Great Commission — the pursuit of worshippers of God — disciples — through worshipping God. When Paul hits the polytheistic city of Athens as a monotheist he adopts a pluralist strategy; one based on listening to the views of the people in Athens, on understanding their idolatrous impulses, and of confidently redirecting those impulses to the true and living God. His confidence is that when the Gospel is presented as a monotheistic truth in a pluralistic culture God will work to draw people back to his design for life.

Societal shifts towards God’s design have happened historically (think Constantine and Rome), and they do happen through Christians living and proclaiming the Gospel, but I’m not entirely sure that a Christian society should be our aim rather than a society of Christians (and the difference is how people who aren’t Christians are accommodated in the laws and institutions of each — ie whether the culture is pluralistic or monotheistic). Ancient cultures were also profoundly different to our individualistic, ‘democratised’ age in that the way to convert a culture was either to conquer it (think Babylon and Israel — or the spread of Babylonian religion to the hearts of most of those they captured (but not all Israel), or Rome and the imperial cult), or to convert the king. Kings functioned as high priests of the civic religion and the very image of God, and so to convert a king was to turn the hearts of the people to a different God (think Jonah in Nineveh, or Nebuchadnezzar’s response and edicts after witnessing God’s work in Daniel, and to some extent, Constantine in Rome). It is pretty unlikely that a society wide shift like this will happen when there isn’t a close connection to the ‘civil law’ and the religion of a nation.

I would argue this approach to voting is only straightforward if you adopt a purist-idealist position and reject pluralism as a valid good. That it isn’t actually straightforward that the best thing for our society is that non-Christians be conformed to our vision of human flourishing, and so our definition of marriage, without the telos — or purpose — of human flourishing and marriage as part of that being established first.

I’d also say this is an odd interpretation of what we are being asked. The question is not ‘what would be best for society’ — to approach it that way automatically leads to adopting an ‘idealist’ position; it begs the question. What we are being asked, literally, is “should the law be changed to allow same-sex couples to marry?” In a secular society that’s an entirely more complicated question about what communities and views a secular government should recognise in its framework. The government’s responsibility is to provide the maximum amount of compromise or breadth for its citizens that can be held by consensus. It’s a tough gig. The government’s definition of marriage, including no-fault divorce, is already different from the Christian view. I marry people according to the rites of the Presbyterian Church which includes and articulates a vision of marriage connected to the telos of marriage — the relationship between Jesus and the church; the government’s definition of marriage is broader than mine, but includes mine.

This is the point at which I disagree significantly with the paper (I also disagree with the way it treats recognition as affirmation, fails to listen to, understand, and respond to the ‘human rights’ argument for same sex marriage by simply blithely dismissing it, and how it sees secular laws as establishing ideals rather than minimums (the state can and does pursue ideals through incentives and campaigns, but there are no incentives being offered to gay couples to marry that they do not already receive). The law is a blunt instrument that recognises things held as common assumptions of the minimum standards of life together, like ‘robbery is wrong’ and governments can incentivise not-robbing with welfare payments, and prevent the evil of robbery by incentivising or subsidising local governments or businesses introducing better lighting and security. Ethics aren’t formed so much by law but by the development of ideals and virtues (and arguably this happens through narratives not law, which is why so much of the Old Testament law is actually narrative even in the little explanations of different rules).

Generous Pluralism, the GIST Paper, and the Priesthood of all believers

This GIST paper was adopted after a lengthy review process, and through much discussion including three face to face meetings and deliberation by flying minute. Throughout the course of the discussion (and before it) it became clear that there were different views about what ‘faithfully living for Jesus in a secular society’ looks like; and so what equipping believers to do that looks like. I suggested we put forward the best case for different responses (an alternative to the majority view, and for it to be clear who held it and who did not, on the committee. In the discussions around the paper the majority of the committee held that we did not want to “give credence” to views other than the no vote being what equips believers to live faithfully for Jesus; even while acknowledging that my position was legitimately within our doctrinal and polity frameworks. This was ultimately why I resigned.

I don’t believe this decision to exclude a possible way to live faithfully for Jesus (and what I think is the best way) fulfils the committee’s charter if there are actually legitimate faithful ways to abstain or vote yes.

I also this fails a fundamentally Reformed principle in how we think of believers, and this principle is part of why I think a confident or generous pluralism within the church, and within the boundaries of orthodoxy, is the best way to equip believers. A confident pluralism isn’t built on the idea that all ideas are equally valid, but rather that we can be confident that the truth will persuade those who are persuaded by truth. That we can be confident, in disagreement, that a priesthood of all believers do not need a priestly or papal authority to interpret Scripture and the times for them. Believing that such a committee writes to equip such a priesthood of all believers (those our charter claims we serve), and that they should apply their wisdom, submit to scripture, and participate in the world according to conscience is the best way to equip believers to live faithfully.

A position of generous pluralism applied to a secular society outside the church probably leads to abstaining, and possibly to voting yes, depending on your ethic (how much a retrieval ethic plays into your thinking and how much you think the law affirms or normalises rather than recognising and retrieving good things from relationships that already exist (where children already exist).

Because a confident, or generous, pluralism relies on the priesthood of all believers and trusts that Christians should come to their own position assessing truth claims in response to Scripture I’m relatively comfortable with space being made for people to hear views other than mine. An example of this is that I host the GIST website, free of charge, on my private server at my cost. People are reading their views at my expense, and I will keep doing this as an act of hospitality though I believe their views are wrong. I also host and only lightly moderate comments and critical responses to things I write. This is a commitment I have to listening, to dialogue, to hospitality, to accommodation of others, to the priesthood of all believers (and a confidence that the truth will persuade those who it persuades), and to pluralism — and the lack of this commitment from others on the committee is in favour of purism-idealism, is fundamentally, why I resigned from the committee.

While the GIST paper tries to hold the created order (or ‘marriage as a creation ordinance)’ in tension with the resurrection; following the Oliver O’Donovan ‘resurrection and moral order’ model (and this was part of our discussions as a committee); the problem with creational ethics (or arguments from God’s design/natural order) that establish a universal good for all people, even non-Christians, is that they do not, in my opinion, sufficiently recognise the supremacy of Jesus or how Jesus fulfils the law and the prophets (because ‘moral law’ is still law we find in the written law of Moses that Jesus claims is written about him). This is a point at which I diverge slightly from the capital R reformed tradition, but where I think I am probably prepared to argue I’m standing in the traditions of the Reformers (sola scriptura and the priesthood of all believers).

Turning to the Reformers for a model of a political theology from our secular context is interesting; the governments operating around the Reformation (for example the German nobility, or Calvin’s Geneva) were not secular but sectarian; and, for example, Luther wrote to the German nobility to call them to act as priests as part of the priesthood of all believers, rather than be led by the pope (a vital thing to convince them of if he was going to make space for the reformation). It’s fair to say that Calvin and Luther weren’t pluralists, they played the sectarian game at the expense of Catholicism or other forms of later Protestantism (see Luther’s Against The Peasants, and of course, his awful treatise on the Jews). When someone claims their political theology is consistent with the Reformed tradition and seeks to apply it to a secular democracy, I get a little concerned.

“It is pure invention that pope, bishops, priests and monks are to be called the “spiritual estate”; princes, lords, artisans, and farmers the “temporal estate.” That is indeed a fine bit of lying and hypocrisy. Yet no one should be frightened by it; and for this reason — viz., that all Christians are truly of the “spiritual estate,” and there is among them no difference at all but that of office, as Paul says in I Corinthians 12:12, We are all one body, yet every member has its own work, where by it serves every other, all because we have one baptism, one Gospel, one faith, and are all alike Christians; for baptism, Gospel and faith alone make us “spiritual” and a Christian people…

Through baptism all of us are consecrated to the priesthood, as St. Peter says in I Peter 2:9, “Ye are a royal priesthood, a priestly kingdom,” and the book of Revelation says, Rev. 5:10 “Thou hast made us by Thy blood to be priests and kings.”

This is an interesting paper from Luther in that it doesn’t provide any sort of model for interacting with a government that is secular or not as faithful as any other members of the priesthood of all believers — instead what his political theology in his context is about is a government he treats as Christian being coerced by a church he holds to be the anti-Christ.

The Reformation was built on an epistemic humility that comes from the challenging of human authority and tradition. Where the GIST committee, in its deliberation, appealed to the Reformed category of a ‘Creation Ordinance’, I’d want to appeal to the Reformed approach to scriptures that sees everything fulfilled in Jesus — even the creation ordinances like work, Sabbath, and marriage. It’s reasonably easy to establish that Jesus is our rest and Lord of the Sabbath, that his resurrection restores our ability to work in a way that is no longer frustrated (1 Cor 15:58, Ephesians 2) — that there’s a telos or purpose to these creation ordinances that is best fulfilled in Christ, so that they can’t universally be understood by idolatrous humans without Jesus, and yet our arguments about protecting marriage or upholding marriage is that we are upholding God’s good design for all people. GIST’s paper is infinitely better than anything the ACL or the Coalition for Marriage is putting out that only argues from creation, in that it includes the infinite — by incorporating the resurrection; but the idea of a creation ordinance that should push us away from accommodating others via a public, generous, pluralism is an idealism that I would argue fails to accommodate the relationship between creation and its redeemer, and the telos of marriage (which doesn’t exist in the new creation except as the relationship between us and Jesus) (Matt 22, Rev 21).

A Confession

I’d served this committee for seven years. In the first two years I was in a minority (with another member) with a majority holding to a different sort of idealism; an idealism not built on the Gospel, but on God’s law or the ‘whole counsel of God’ (with no sense of how God’s whole counsel is fulfilled in Jesus). We orchestrated a changing of the guard on this committee that was not generous or pluralistic; we excluded a voice from the committee that was a legitimate representation of members of the Presbyterian Church of Queensland.

We pursued a platform narrower than the breadth of the church and so alienated a percentage of our members; I’ve come to regret this, while being proud of our record (and despite the committee being returned unopposed year on year since). I don’t think excluding voices is the best way to fulfil our charter, but rather a poly-phonic approach where a range of faithful options are given to the faithful — our priesthood — in order to be weighed up. This will be a challenge within the assembly of Queensland where there is a large amount of accord, but a much larger challenge within the Presbyterian Church of Queensland, which is broader (and more fractured).

Conclusion

At present in the Presbyterian denomination our committees are operating like priests or bishops; sending missives to our churches that carry a sort of authority they should not be granted in our polity; I understand the efficiencies created by governance and operations via committee, but if Luther’s priesthood of all believers is truly a fundamental principle of Reformed operation in the world we should be more comfortable and confident that people being transformed by the Spirit and facing the complexity of life in our secular world will act according to conscience and in submission to God’s word, but might operate faithfully as Christians anywhere between idealism, pragmatism and pluralism, as purists or ironists; and if we put the purist-idealists in charge (or our committees function from that framework) we might significantly narrow the church and limit our voice and imagination; cutting off opportunities for Gospel-hearted apologetics from those who might walk through our idol-saturated streets and engage differently with our idol worshipping neighbours.

September 14, 2017