It has become apparent that in a recent Facebook post some language I used has caused some brothers and sisters in the Presbyterian Church of Australia to stumble; they have because of a communication failure assumed the worst of me, and so circulated my post to senior members of my denomination nationally and locally worried that I have veered into apostasy.

I have to own this failure to communicate, and it has caused me to reflect on how I use words, and how I use social media.

I believe the unity of the church is profoundly important — matched only in importance by the mission of the church — and, I believe the unity of the church is part of the mission of the church. So we live in perplexing times.

I use words in a particular way. I understand the way I use words — and the way I frame my writing and my speech according to my audience. That is part of the communicative act — it’s part of using words to describe and persuade.

The meaning of words changes rapidly, and, in an increasingly fragmented age where we have no common, fixed, perhaps even transcendent basis for the meaning of words (that isn’t to say I do not think there is a transcendent basis for the meaning of words) we have to nimbly communicate through confusion around meaning, both keeping pace with the changing meaning of words and contesting their meaning. It’s a challenge.

Two examples of the contest of not only words, but phrases — especially the way this contest plays out in a “culture war” setting — are the phrase “black lives matter” and the terminology used (by Christians or otherwise) to describe the experience of same sex attraction (whether a person uses a letter from the LGBTIQA+ acronym, like “gay,” or some other terminology including, for example “same sex attraction.”

I’ve outlined before that my philosophy of language is descriptive rather than prescriptive and that so much pain within conversations is caused by people approaching words differently, but on the back of some fresh experience of this pain, I’m using this post to provide certain clarification around both my use of language, social media, and approach to relationships from here on in.

More than 10% of my congregation are people whose experiences are in the what you might call ‘sexual minority’ category — that is, those who might describe themselves as “same sex attracted” or LGBTIQA+. This is not accidental; it is the result of years of advocacy on behalf of Christians in this category who are seeking to live faithfully as followers of Jesus; and by this, I mean, seeking to obey the Lord Jesus, as we understand the Scriptures, within a traditional sexual ethic — namely, our church teaches that marriage is between one man and one woman, and sex outside of marriage is adultery, and, following the teaching of Jesus, that lust is, itself, idolatry.

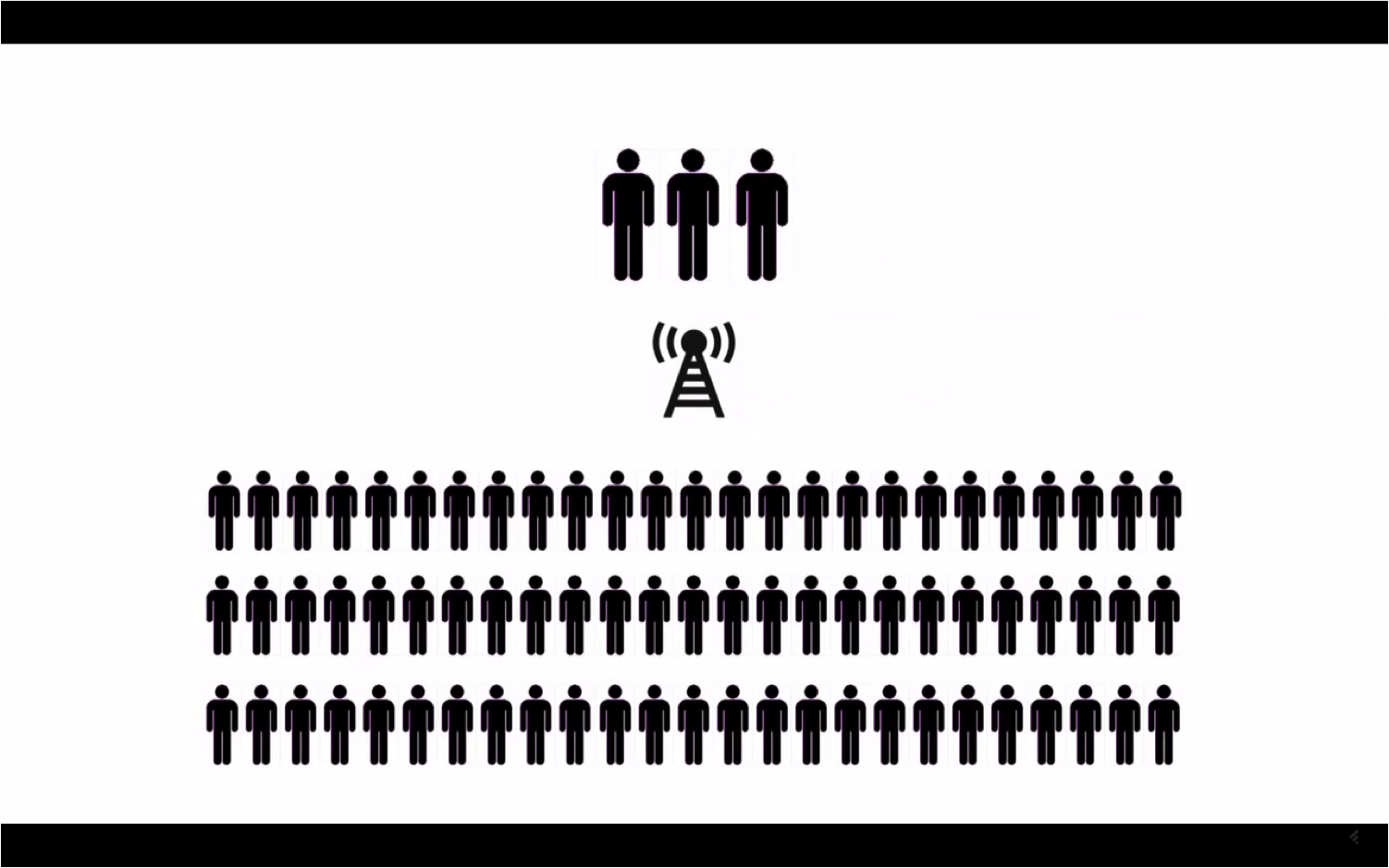

I’ll say up top that I’m a reluctant public commentator on matters of Christianity; I do not wish to carve out a platform or profile. I do not check stats for this blog. I do not advertise. This website costs me at least a thousand dollars a year to register, and operate. I am happy to write for external publications because I enjoy crafting articles for publication, but I do not wish to court controversy or be a culture warrior. I am committed, as much as possible, to writing constructive or ‘generative’ pieces into the future, rather than deconstruction and critique. I am a public commentator on issues of public Christianity because I am a pastor and I care about my flock. I think part of the role of a pastor is to make space for your brothers and sisters to flourish, laying down your own strength while serving the chief shepherd. I have the ability and the privilege that allows me to speak as someone who will be heard. So I do. My social media accounts are not ‘platform building exercises’, though, until now, I have added any friend who has requested to connect where they have had more than 25 mutual friends, or reached out to ask questions about things I’ve written.

I am, first and foremost, a person. I am human. I am fallible. I think out loud. That gets me into trouble — but I am a person who aims to operate with integrity and conviction. I want to pursue truth rather than brand loyalty, a following, or popularity. So I am prepared to say unpopular things that challenge status quos.

I am also a husband and father. I have a responsibility to my family. I want to live in a world where it is plausible for my kids to follow Jesus, not because I think this relies on human effort, but because I understand that God works both by his Spirit and ordinary human means to bring people to himself, and my deep desire is for a church community that nourishes my faith, my wife’s faith, and my children’s faith. Given one of the major stumbling blocks for belief in the Gospel seems to be how Christians treat the LGBTIQA+ community, I think it is incredibly important that my kids have people in their lives (in their ‘plausibility structure’ who are both LGBTIQA+ and committed to the way of Jesus.

I am, thirdly, a pastor. I love my church family. I love my LGBTIQA+ brothers and sisters who are modelling costly discipleship and rich community. I believe these brothers and sisters in our church community and the wider church are something like the Desert Fathers, those voices who withdrew from ordinary life and so were able to spot the idolatrous culture of the city and call it out. Our culture worships sex, desire-fulfilment, and individual self-expression and identity formation through choice/consumerism; it is courageous and prophetic to stand against that tide and these brothers and sisters model this in the area of sexuality in ways that have much to teach us. I will, as a pastor, give my strength, privilege, and voice, to carve out space for them to flourish, and to serve our church — and I will advocate for them when they find themselves under attack from the wolves, or bitey sheep.

Fourthly, I am committed to the work of evangelism — not only in a commitment to preaching and living the Gospel as a church community, but to making a compelling case for Christianity for those in a post-Christian, post-modern (maybe meta-modern) world. I’m not interested in re-Christianising only the politically conservative, for whom Christianity aligns nicely with a political agenda, but with those who feel most aggrieved by the way Christians have been caught up with empire. I want to take the Gospel to the marginalised, into the issues that groups like the ACL ignore, and into the lives and stories of my friends and neighbours. I believe that one of the best ways to do this is to listen, and to adopt a posture of hospitality. When I use social media, just as when I use my dining room table or backyard, I am inviting people not into a ‘public’ space, but a space that is private and where they are able to enter a conversation. I enjoy that these conversations can involve people from across the political spectrum, and religious spectrum — I think, for example, the church is at its best when it has that sort of diversity in the mix. I confess my posts have become ‘too public’ to do this well; but the primary audience of my social media is not ‘the church’, it’s ‘the world’ — and my primary use of social media (I hope) is not performative ‘image’ or ‘platform’ building, but to present myself as I am, and to engage in virtual, mediated, relationship with people with the aim of taking that relationship into the real world over a meal, or a drink, or at church. I want people to engage in conversation with me in the hope that the conversation will leave them feeling warmer towards Jesus than they did before engaging.

Any ‘public Christianity’ I do is an expression of these three roles — and my social media use is not ‘public Christianity’ (though admittedly it has become more and more that way without careful stewardship). My posts aim to be pastoral rather than political; I want to resist the politicisation of people and their experiences (both in church politics and worldly politics). This does not mean my posts are not political — they are in two ways; firstly I believe the local church (and the wider church) is a political institution — an expression of the kingdom of God, and that the Gospel itself is political (in that we declare that the resurrected Jesus is Lord of heaven and earth). As we operate as a local community, and that operation is reflected (though mediated) in our ‘social media’, that will be ‘political’ in a subversive way (I hope). Secondly, that pastoral stance produces a political stance, especially in a world that is so dominated by an ‘us and them’ culture war that uses vulnerable people as political footballs without caring how hard they get kicked. Some of my ‘politics’ involves kicking the people kicking vulnerable people (and I’d like to do that less), some of it involves putting my hand up to get kicked instead (I’d like to do that more), while some of it involves asking people to play a different game.

From here on in I’ll be changing the settings on my posts to friends only to minimise engagement with those who might feel my posts are a stumbling block, and to make it clearer that I am not particularly interested in ‘in house’ conversation with other members of the Presbyterian Church of Australia in that forum (should my posts cause those brethren to stumble). There are other forums for that sort of conversation but you, my dear brothers and sisters in the PCA, are not the intended audience for my Facebook profile, it is given to the roles I’ve described above — as person, husband, father, pastor, and friend. St. Eutychus does have a Facebook page as a hangover from when I checked stats and thought a platform was important — I will continue to post articles there for wider engagement. I am happy to have debates there.

If you are a Facebook friend from the PCA but my posts trouble you, you are, of course, welcome to read along, but at the point that you feel offended or a sense of disunity, I invite you to contact me directly rather than kicking the denominational rumour mill into overdrive. I will do my best to accommodate you in contexts where we are in conversation.

In the case of the offending post I both described a member of my congregation as “coming out”, and, in the comments I described people who hold to a traditional sexual ethic as “celibate gay Christians”. The latter is offensive to some, the former caused significant confusion for many brethren around the nation despite the immediate clarification offered in the comments section of the post.

I want to briefly outline why I use “gay Christian” quite happily to describe members in good standing of my church community (when they so choose), and why “coming out” is something I believe is worth celebrating — but the main point of this post is to explain why and how my use of social media as a tool not for communicating within the people of God, but as part of God’s mission to the world will shape the way I use language, and what expectations I will then operate with when it comes to people interacting with my social media presence from here on out.

I don’t believe that a person who calls themselves a “gay Christian” is making an ontological identity claim where their sexual preference is competing with their union with Christ in defining their personhood.

My understanding (and I’ll note here that I am cishet, married, and have no experience navigating life as a sexual minority) is that for my brothers and sisters who have been aware of their sexual orientation from quite early in life, that orientation is a significant aspect of their narrative, and their experience navigating the world and relationships. If a Christian, in good standing in a church community, told either a non-Christian or a fellow Christian that they are “gay” or “lesbian”, I think it’s reasonable to assume that both the church friend or the non-Christian friend would have unhelpful immediate assumptions about what that means for their faith; namely, the assumption is that one cannot be both “gay” and faithfully Christian (leaving aside “affirming” theology and its claims for the moment — and… I use those scare quotes because I think, ultimately, asking a ‘theology’ to do the work of personal affirmation is tricky (not that that is always the case here), and we’re meant to align our lives with theological truth, rather than the other way around… but I think almost all the ‘theology’ on the table here, whether supporting a ‘traditional’ sexual ethic or embracing same sex relationships ends up affirming a liberal view of the individual and identity… and so I don’t necessarily see it as totally distinct, much as I don’t see ‘left’ as all that distinct from ‘right’ politically). It seems to me that these individuals need language that can describe their experience and their religious commitments in efficient ways.

I don’t believe that identity is an airtight theological category — in fact — I think it’s a trojan horse that slips in all sorts of idolatrous anthropology built from expressive individualism into the church (and, that, for those who have issues with what ‘gay’ means in the ear of the average punter, it would be interesting for them to account for what ‘identity’ means in both a therapeutic and sociological/recognition sense such that we should ask if it’s a legitimate category to be putting at the heart of our theological anthropology). So I don’t believe that someone who says they are a “gay Christian” is making an ontological identity claim, but rather describing their experience — and that the qualifier “celibate” helps further answer the questions and objections that the hypothetical person they speak to might have.

I understand that for many the word “gay” is associated with homosexual practice, and that for many Christians the debate about whether same sex attraction itself is sinfully disordered (a form of concupiscence), or whether it is lust and sex (the activities prohibited in the Bible) that are sinful expressions of an idolatrous rejection of God’s design for human sexuality, such that the word “gay” is an affirmation of a sinful and disordered aspect of a person’s life. I acknowledge that for both these groups (and they overlap of course) the use of the word “gay” is something like participating in idolatry. And yet, when I hear how my LGBTIQA+ brethren use terms like “gay” or “queer” they are doing something quite different with their language and it seems to me that “same sex attracted” is a label that thoroughly reduces a person’s experience to their sexual desire, and for those in the ‘concupiscence’ camp, that seems to me to be altogether worse (eg “I am a same sex attracted Christian”).

My “celibate gay,” queer, and LGBTIQA+ Christian friends are using language descriptively to describe their experience; inasmuch as they are making an “identity claim” it is a claim around experience/narrative, not ontology. And, to the extent that they are describing an experience it is an experience outside my own, and I want to be careful to listen well to them and to not think it is my job to control how language is used (remember, I am a descriptivist, not a prescriptivist). I think it’s particularly worth noting that words like “Gay” and “Queer” have been thoroughly contested, and the definitions in popular usage have dramatically shifted over time. The language keeps changing and to abandon the contest for words is to ensure the devil gets all the good music. Additionally, I’d note that the variety of experiences of attraction (sexual or otherwise) is consistently being nuanced as people have freedom to breakaway from historically rigid categories, and so, different labels are being given to different experiences of attraction at breakneck speed (did you know, for example, that because of the dynamic of ‘asexuality’ being unpacked in various ways, and in order to accommodate the different experiences of same sex attraction, people within the LGBTIQA+ umbrella will now make significant distinctions between romantic and sexual attraction, such that you might experience being romantically attracted to one sex, but sexually attracted to another). It pays to listen carefully in order to understand how language is being used, rather than insist on word meanings if one wants to have a conversation with another person; otherwise it’s like a Protestant theologian talking to a Catholic — we use all the same words, but have vastly different meanings.

This does mean that for Christians whose experience life as sexual minorities, they are navigating two sets of language — the expectation to meet certain theological shibboleths within the church, but also, often, actively working to make sense of their own experience as they navigate the complexity of positioning themselves in both the church and the world. Explaining to their church friends why they aren’t pursuing marriage with a person of the opposite sex, and to the world why they aren’t pursuing their attraction into desire (or lust), a relationship, or sexual activity. And we want to police their language use. Give them a break.

Also, I’d note that the terminology used — specifically ‘gay’ — is a broader and much more inclusive label than “same sex attraction,” which reduces a person’s experience — and perhaps even their identity — to ‘sexual attraction,’ whereas, so far as I understand it from conversations with my friends, to adopt a more inclusive label like gay, or queer, is to acknowledge a variety of shared experiences (and solidarity) with other sexual minorities who have to navigate a world (and church) that brings a degree of pain, trauma, and exclusion (even just from normal expectations around marriage and procreation). To police that particular term because it is “only ever about sex” is to choose a false prescriptive definition, and to significantly limit the semantic domain of a word (where there aren’t many better ones) that carries much more weight than simply some sort of idolatrous ontological identity claim built around sexual practice. It’s to make the mistake of elevating sex to the supreme position in a person’s life, and to flatten a range of narrative type experiences into some nebulous category of ‘identity’. In short, it’s a failure to listen.

My friend and colleague Matthew Ventura has written about the difficulty choosing the right language according to the audience he is speaking to, and about how he uses words not to make an “identity claim” (whatever that means) but in a paradigm of differentiation and solidarity. Here’s his description of why he uses the terminology he chooses when using the descriptor “celibate gay Christian.”

“A second approach seeks to step towards LGBTIQ people and say ‘I’m one of you. We can relate to each other’s experiences of being sexual minorities.’ Of course, for the celibate single same-sex attracted Christian, there will be plenty of areas of our experience that are not common to non-Christian LGBTIQ people, but this approach aims to highlight the commonalities and express solidarity. The motivations for this approach can either be missional (taking a step into ‘their world’ with the hope of eventually welcoming them into ‘our world’ of God’s family), hospitable (seeking to bring other marginalised people in and offer them a place of belonging in a safe and loving queer community) or a personal motivation (seeking a community where one can feel understood, supported and loved in their minority experience), or any combination of these motivations.”

Now, I’m not gay, but I think the reasons he gives for someone who shares that experience to use particular terminology also applies to the church in its participation in God’s mission to the world.

Matt makes a couple of observations on how people on the “differentiation” end of this spectrum operate, and how those seeking solidarity with the LGBTIQA+ community operate and the risks connected to these positions; the risk he describes here is the one my post fell foul of this week.

By associating themselves so closely with other LGBTIQ people, “celibate gay Christians” have risked causing scandal. Regardless of their actual moral conduct, celibate gay Christians often perceived by other Christians as being deviant, theologically liberal, or morally bankrupt simply by their close association with other gay people. Understandably, many Christians would prefer to avoid causing scandal by opting for the safety of unambiguous terms that clearly differentiate themselves.

That’s a useful framework. Ron Belgau at Spiritual Friendship has written about language being used narratively, or phenomenologically, rather than ontologically, which I think is also useful. It also fits better with a sort of ‘narrative ontology’ that sees us persons given bodies and lives to steward by God in accordance with the telos given to us by his story (rather than being authors of our own destiny and identity). In his excellent book A War of Loves, David Bennett spells out seven reasons behind his choice of language, a couple are worth quoting at length.

“The word gay does not necessarily refer to sexual behaviour; it can just as easily refer to one’s sexual preference or orientation and say nothing, one way or the other, about how one is choosing to express that orientation. So, whereas “stealing Christian” describes a believer who actively steals as an acted behaviour, “gay Christian” may simply refer to one’s orientation and nothing more. This is why I rarely, if ever, use the phrase gay Christian without adding the adjective celibate, meaning committed to a life of chasteness in Christ. To call myself a celibate gay Christian specifies both my sexual orientation and the way I’m choosing to live it out. We have all been impacted by the fall. The particular challenge for the majority of gay or same-sex-attracted Christians is untangling the sinful aspect of same-sex attraction from their God-given desire for intimacy. Some find that this need for human intimacy is met in celibate friendships; a smaller group report a special God-given attraction to a particular opposite-sex partner in a mixed-orientation marriage. But most side B Christians choose celibacy.”

Another reason he gives is to speak prophetically to the surrounding world.

“Those of us who are orthodox or traditional Christians and who are gay or SSA need to reclaim our space in the conversation over sexuality back from the secular culture. While we have shared experience of same-sex desires with those who are gay and seek to be in gay marriages, including dealing with them in a fallen world that is prejudiced and unloving, we are different, and this needs to be reflected in how we understand what it means to be gay or SSA in broader society. Also, people like me have benefited from the gay rights movement in many ways and would not be able to live the open life we do without many of these wins for human dignity, but we don’t want that movement to spell the deprivation of our rights to live in churches that support our choices and obedience to Christ. We can identify with many of its wins for the human dignity of LGBTQI/SSA people, including employment rights, protections from hate crimes, and anti-discrimination laws, even if we may disagree on sexual ethics.”

His final reason lines up with Matt’s “solidarity” framework.

“My seventh and final reason is invitational. Mainstream secular culture feels alienated by terms like same-sex attracted and gay lifestyle. There is no monolithic gay lifestyle. The term same-sex attracted sounds medical, like a diagnosis—reminiscent of when same-sex desire was seen as a disease. Such terms can place hindrances in the way of those who need to hear the gospel message. When I entered the church and heard these terms, they kept me from feeling included and understood. On the other hand, the term gay is positive and welcoming for those who are gay or SSA. Christians would do well to focus on removing boundaries—existential, intellectual, and spiritual—in order to know the good news for our own sexual brokenness, and then, further, to share the good news humbly from this place with others.”

Which is to say if we listen to our Christian brothers and sisters whose lived experience we’re talking about, and we’re wanting to speak the good news of Jesus in ways that are compelling to others who share that experience, there might be a 1 Corinthians 9 “all things to all people” rationale for using this language — even if, for Paul, sometimes becoming like the Greeks was massively problematic for Jewish Christians. But I’ll unpack more of this below.

My observation of the status quo — including my own experience this week — is that we can spend a lot of time trying to decide what specific words always mean and so interpret them that way, or we can spend a lot of time trying to understand what people mean when they use words. A lot of the consternation about my post would’ve been lessened by less insistence that the words I used always mean a thing they don’t, and more seeking to understand what was being communicated. As someone who uses words though, I do have a responsibility to ensure my choice of words is connected to clear meaning for my audience. The catch is we all have so many audiences, and so many of our audiences use words differently.

All that said, I do not believe that a person’s sexual attraction is inevitably a personal choice (though I am comfortable that there is a degree of fluidity experienced by a variety of people and sexual and romantic attraction is complicated). I do not think a same sex attracted person, or a person whose experience of gender does not conform with their biological sex, needs to ‘become straight’ or even ‘become not LGBTIQA+’ in order to put their trust in Jesus; I think to live with Jesus as Lord will have implications for how we use our bodies and desires as part of our Christian vocation — as we love the Lord our God with all our heart, soul, mind and strength. And this will mean faithfully aligning one’s sexual behaviour, and desires, with the Bible (that said, I also believe church communities should be places where people come to hear the Bible taught before they have decided what that means, not having decided what that means), and that acknowledge that there is disagreement on how to interpret the Biblical data (personally, I find the arguments for an ‘affirming position’ on same sex relationships unconvincing). This means I believe it is fantastic for a person, and for their church community, if someone whose experiences (including, but not limited to attraction and/or desire) fall within the LGBTIQA+ spectrum, “comes out” and shares those experiences with vulnerability and trust, in order to be fully known, loved, and supported in their pursuit of faithfulness.

So, with all those bits of data in place — the reason I use the language I do — both the description “celibate gay Christian” for those who self-describe that way, and “coming out” for people who embrace the vulnerability of being known and supported, rather than closeted, spins out of my relationships and my sense of call (as a pastor with an evangelistic commitment to marginalised people groups in a post Christian world). I appreciate that this creates challenges for my brothers and sisters much like Paul’s ‘gentileness’ was a problem for the church in Jerusalem, and that perhaps I could work harder at being a “Presbyterian to win the Presbyterians”…

But here’s some of the theological framework behind this choice that I have alluded to above — I believe the choice of terminology here is roughly equivalent to idol meat in Corinth.

In 1 Corinthians, Paul is addressing a situation where the moral freedom of Christians in the church — to eat meat from the local marketplace that came from local temples — was a stumbling block for other Christians in the church. Paul tried to balance the competing priorities of unity and mission; there are, in 1 Corinthians, very good reasons to eat gentile food — namely, to win gentiles to Jesus. Paul describes his missionary flexibility (offensive both to non-Christian Jews, and to Christian Jews, when he lands in Jerusalem) in 1 Corinthians 9, and unpacks his unity-first ethic in chapters 8 and 10. He does a few key things in his presentation of the tension. First, he makes it clear that idol meat is not illicit — that to eat it is not actually to definitively participate in idolatry — much as those celibate gay Christians who use the descriptor work very hard to make it clear that they aren’t endorsing idolatrous sexuality (even if other people who use the words “gay Christian” might be — just as some Corinthians who claimed to be Christians who ate meat in the temples might’ve been). Paul makes it clear that the stronger brothers and sisters in the church are actually correct. Paul connects eating this meat with eating with non-Christians (in chapter 10), saying one should stop doing it in that context at the point it confuses non-Christians about whether or not you are affirming their idol, but that is relational rather than caught up in some prescriptive meaning of the symbol of the meat. Paul wants Christians to eat with non-Christians as an extension of the mission he describes in chapter 9 — and he wants both differentiation (not being idolaters) and solidarity (being a Greek to win the Greeks) to be part of the pattern of engagement. His guiding principles, expressed in chapter 10 are the glory of God, the unity of the church, and the good of others so they might be saved.

So whether you eat or drink or whatever you do, do it all for the glory of God. Do not cause anyone to stumble, whether Jews, Greeks or the church of God— even as I try to please everyone in every way. For I am not seeking my own good but the good of many, so that they may be saved.

The tricky navigating act here is that Paul prioritises the protection of the weaker brother in 1 Corinthians 8.

He writes:

Be careful, however, that the exercise of your rights does not become a stumbling block to the weak. For if someone with a weak conscience sees you, with all your knowledge, eating in an idol’s temple, won’t that person be emboldened to eat what is sacrificed to idols? So this weak brother or sister, for whom Christ died, is destroyed by your knowledge. When you sin against them in this way and wound their weak conscience, you sin against Christ. Therefore, if what I eat causes my brother or sister to fall into sin, I will never eat meat again, so that I will not cause them to fall.

Now, in drawing and applying this analogy to the current circumstance I probably shouldn’t just assume the position of the “stronger brother”, but it is clear that my use of my freedoms (knowing, as I do, that despite my language use I have not succumbed to idolatry but am using language for pastoral, evangelistic, and prophetic reasons in a contest for meaning) have caused brothers and sisters to stumble, thinking that I am affirming idolatry. There is an onus on me here to be more careful with my language in church facing contexts. I assume Paul didn’t police the language (or meat eating) of Christians eating meat with their gentile friends without weaker brothers around — because he gives guidelines for how they should do that (in chapter 10). This is why my response to the present imbroglio is to more clearly define my social media use as ‘world facing’ rather than ‘denomination facing’ — I’d like to use it as a dinner party, rather than an in house church meeting.

But I will say, too, that the idea that Christians in various minority experiences — in this case sexual minorities — should position themselves as the stronger brothers and moderate their language, while existing on the margins of our institutions and having very little ‘social capital’ within the church; where their language is institutionally policed, and where their employment or sense of belonging not only in church communities but their biological families is always at risk (and often these relationships are sources of trauma-through-differentiation rather than solidarity) just seems intuitively wrong to me. We ask these brothers and sisters to do so much additional emotional, spiritual, and existential labour just to exist in our communities. Maybe we could flip the script a little bit and do all we can not to cause them to stumble — even if that means adopting terminology we are initially uncomfortable with, and joining them in solidarity in our shared pursuit of God’s glory, and the mission of the Gospel.