There is no theological topic I read about as much as what it means to be made in the image of God; it was the question at the heart of my thesis, but my obsession didn’t end when I graduated. It’s a question at the heart of what Christians believe it means not just to be human but to flourish as humans; and the answers to the question have been used to achieve many great things for societies influenced by Christians. There’s no doubt that being made in God’s image is part of what sets us apart from animals, and part of what gives us dignity and an inherent value (see Genesis 9:6) — there are questions about what sort of dignity it carries or what it entails to bear God’s image, and how much we as humans can deliberately or accidentally eradicate that image in pursuit of our own purposes (and very clear evidence about what happens when we refuse to see fellow humans as image bearers).

In church tradition and in the developments of doctrine or ‘systematic theology’ there has been much ink spilled on what it means for humans to be the imago dei — that’s Latin for ‘image of God’. The early church, once it got established and there were people who had the time and space to be theologians, wrote in Latin so there’s plenty of latinisms hanging around in systematic theology/doctrine discussions still. Sometimes the development of systematic theology fails to take into account developments in Biblical scholarship; and I’m pretty firmly in the camp that our theological understanding of the world comes from always going back to the source (ad fontes — in Latin), the Bible, rather than from church tradition (though church tradition does limit totally novel and heretical readings of the source material).

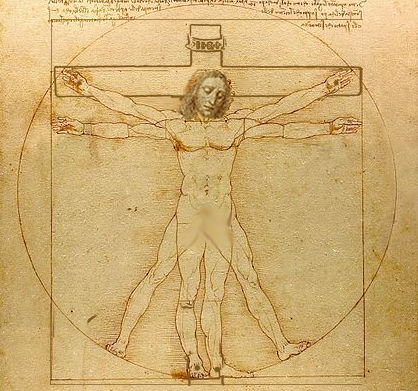

Lots of the stuff I read that digs into what it means to be the ‘imago dei’ is built from church traditions rightly affirming the inherent dignity of the person; and increasingly the embodied reality of our humanity; you can’t be an image and not be ‘physical’ — and that’s true. But it’s often the case that we bring ideas to the text of the Bible that are foreign to its thought world (and developed through the history of the church); rather than trying to get into the world, and once an idea gets a certain sort of momentum or meaning, it’s very hard to rein it back in. This isn’t to say there aren’t systematic theologians grappling with how the text of the Bible shapes a theological concept like the ‘imago dei’; but it does mean we need to be careful of the certain sort of freight tradition brings with it when we use terms, and I think it’s time to start resisting some of that freight to ensure we’re able to do the ad fontes work of building our understanding of who God is and who we are in relation to him.

Here’s my not so passive act of resistance; I’m happy to talk in english about being made in the ‘image of God’ (not the imago dei) simply because it is clear (more perspicuous — more Latin) and less pretentious (also more latin), but if we’re going to get into the nuts and bolts of the meaning of these words I’m not going to indulge the Latin game. I’m going to be talking ‘selem elohim’ (sometimes ‘tselem’ because the Hebrew letter צ rolls that way). This reminds us of the foreignness of the world of the text to our world (in ways that help us not to forget that this is about more than language — and includes how we understand, for example, the place of the supernatural and the reality of a spiritual realm, which underpins the Genesis story but not many modern discussions around anthropology). It reminds us that we’re always translating. It also reminds us that there’s a gap between the institutional church as it unfolds through history for good and for ill, and the experience of Israel and how Jesus fulfils the Old Testament and its expectations and shapes the church and its theology (rather than our understanding of God ’emerging’ and ‘progressing’ beyond the ‘exact representation of God’s being’ walking the earth ala Hebrews 1).

Here’s a few things from Biblical scholarship (selem elohim) I reckon lots of modern systematic theology (imago dei stuff), especially at the ‘popular level’ misses.

- That the word ‘image’, when it’s not about our role as humans, is almost exclusively used for idol statues (one exception is the weird models of the tumours in the ark in 1 Samuel).

- That the word ‘selem’ is what’s called a ‘cognate’ the same consonants are found lumped together in the ancient near east (and vowels are a later edition to the written word); and it has the same meaning in those other nations which establishes a particular context for its use. I’ve written elsewhere about how a ritual for giving life to a ‘slm’ in nations outside Israel parallels in a fascinating way with Genesis 2.

- That to ‘be a thing’ (ontology) in the ancient world, including to be ‘created’ (Hebrew ‘bara’) in the Old Testament was to have a function; to be a selem elohim was to do something in particular; a vocation. If we’re not doing it, there’s a question as to how much our ‘material’ is actually being the thing we’re made to be. So there’s a question, from the Biblical narrative, as to how much the ‘imago dei’ is a permanent imprint rather than a purpose that we might systematically eradicate. The human equivalent to the ‘selem elohim’ outside of Israel was the king-as-god (who’d ultimately become part of the gods of a nation).

- There’s are many important distinctions between Israel’s ‘selem elohims’ and the nation’s. In the nations around Israel people make images and the gods decide to live in them if they tick the right boxes; in Israel’s story — God breathes life into living images. In the nations only the king is ‘godlike’, in Israel’s story all of us are rulers of God’s world.

- This understanding of what it means to be human has some pretty big implications for how we understand human failure — sin — as a failure to uphold God’s image and the pursuit of other ‘images’ that we make for ourselves. All theology is integrated.

- That ‘male and female’ carry out this role together means we’re not simply talking about the ‘imago dei’ being an inherent dignity to the individual thing, but something we carry out in relationship with each other (and the God whose image we bear). The plurals in Genesis 1:26-27 and their significance are debated beyond this (whether it’s the Trinity or God addressing the heavenly court room, for example), but what is reasonably clear (including from Genesis 2) is that a man alone isn’t fully fit for purpose. The Old Testament theologian John Walton makes the case that ‘being’ in the ancient world isn’t just about ‘function’ but ‘function in relationship with everything else’

- There’s a plot line that runs through the Bible where other ‘selems’ form the heart of the Israelite imagination of the good life, and where instead of being God’s images, Israel is conformed into the image of other gods. When Israel entered the nations they were to ‘destroy all their carved images and their cast idols’ (Numbers 33:52), which they do at least in their own land in 2 Kings when they get rid of the temple of Baal (2 Kings 11:18). Israel is constantly warned (in the Law, Psalms, and Prophets) to be God’s representatives, emerging through the smelting furnace of exodus, rather than to worship idols — the warning is they will become what they behold. Breathless and dead. Or the images of the breathing, life-giving, God.

- This line creates a better ‘Biblical Theology’ or narrative of fulfilment where Jesus, the exact representation of God’s being (Hebrews 1) and the ‘image of the invisible God’ (Colossians 1) is the new pattern for our redeemed humanity that we’re transformed into by the gift of God’s spirit on top of the breath of life (1 Corinthians 15, Romans 8). There’s admittedly a jump from Hebrew to Greek in the move from Old to New Testament, but the Greek translation of the Old Testament (the LXX) helps track that jump for us.

What it means to be made in the image of God is fascinating and important, and a vibrant part of the narrative of the Bible. It’d be a shame to remove it from that context and make it mean all sorts of other good things. The best systematic theology already deals with lots of the ideas above — and these ideas make the image of God a pretty big deal — but the best understanding of what the flourishing human life looks like; caught up with who we were made to be comes from going back to the text of the Bible and seeing what it really says and means, letting the Bible shape our world, rather than our world (and traditions) shape how we read the Bible (though this is more like a dialogue than a thing where we pit one against the other).

Join the resistance.