Back when Noah came out on the silver screen I wrote a review for our church website called 13 Things to know about Noah, a little known fact is that before I wrote that piece, I wrote a 7,000 word ‘review’ that never saw the light of day. It’s on TV tonight. It just started. So here, if you want to read 7,000 words, is the unreleased, uncut, extended edition of that post.

There are lots of reviews of Darren Aronofsky’s take on the story of Noah floating around the vast oceans of the Internet. Lots of these reviews, especially those from Christians, aren’t particularly enamoured with the latest Hollywood treatment of a Biblical epic.

Noah is a challenging movie that will make you think about the depth of human sin, how we should relate to each other and our planet, the emotional cost of judgment and justice, the need for salvation, and ultimately it will make you ask questions about who God is, and if the God presented by the movie Noah is the God who steps into the muck of creation, in Jesus, to save us.

The God of Noah is not the God of the Bible, but Noah is a powerful cultural text for us to engage with to shape our thinking.

The God of the Bible is fundamentally interested in the human race, in relationship with humanity – and invests himself into transforming our dark and broken hearts.

This review will consider how we, as Christians, should respond to movies like Noah, and then explore some of the theologically rich themes that Noah prompts us to think about.

It won’t contain much hand wringing – and, spoiler alert, it’s main ‘criticism’ will be that my own worldview leads me to interpret the source material differently and to engage with the worldview presented in the movie critically. Engaged criticism is a perfectly appropriate response to art – provided we’re doing our best to understand the art and engage on its terms – and you can simultaneously appreciate a text and criticise its message.

Art exists to be critiqued and talked about – not to be swallowed as some sort of dogmatic didactic text that tells you what you most certainly think and do.

Noah provides a platform not just for fruitful discussion between Christians and the movie going public, but most importantly for us to reflect on what we believe and why it is important that our God is different to Noah’s. There are a few points where Noah’s theology is particularly interesting discussed in the second half of the post.

This is a long review, but it’s made to be skimmed as much as pored over – because everybody responds to art differently so different parts of this engaging with Noah as a text will appeal to different people.

Note – It’s going to be complicated talking about the four different Noahs here – there’s Noah the movie, the Noah narrative in The Bible, and the two characters – Aronofsky’s Noah, and the Biblical Noah. The movie will be italicised, and those other distinctions will be made as we go, or apparent as a result of context…

NOAH AS ART. NOAH AS TEXT. NOAH AS STORY

I had incredibly low expectations going into the cinema on Monday night – I’ve been strongly affected by previous Aronofsky vehicles like Requiem for a Dream and The Wrestler, but I’d read and watched so much negativity about this movie that I thought it was going to be a disaster. It wasn’t.

Let me make a couple of important points right up front.

Noah isn’t a Christian movie. From the interviews I’ve read – Aronofsky is a “cultural Jew” who drew on a range of Jewish sources, who also has a Catholic background, and he says he has belief in the Biblical God.

Noah is a movie that makes serious attempts to grapple with big theological questions – but many of the reviews around the web operate as though Noah is a story that belongs to evangelical Christians. Aronofsky chose to make Noah because he grew up with the story – both in the Jewish and Catholic traditions. While we, as Christians, believe the story of Noah only makes sense if it’s read in the light of Jesus (because we think the whole Bible points us to Jesus), the story has a place in Aronofsky’s heritage too.

READING NOAH AS A TEXT

A movie is a “text.” It’s important to read texts on their own terms – to interpret according to genre, to the intention of the author, to review things based on the meaning the text is trying to convey (especially if the author of the text tells us what that is). That’s common courtesy. If you’re going to enter into a dialogue with someone or something, it’s polite to understand the position you’re engaging with.

Plenty of reviews have torn Noah to shreds because it isn’t faithful to the Biblical narrative. This is an understandable criticism, because the story of Noah is one we hold dear, but it assumes that Darren Aronofsky has a responsibility to present a text according to our worldview, rather than his own.

This is an odd view of art and the artist. Or of a text and its author.

It’s also an interesting view of the ownership of an ancient text that belongs to many traditions – including Christians. We can’t assume that there were no storytellers telling the story of Noah and the flood before Moses wrote it down a long time after the fact. While we may believe we have the truest telling of the story that doesn’t give us exclusive rights to tell it or to criticise people for not telling it our way.

Noah is a creative use of a story contained in the Bible to present a worldview, sure, and this worldview is theological – it’s just not about the Christian God because there is no sense that the story is connected to Jesus.

Here’s perhaps the greatest irony in the online outrage about Noah. Harnessing the Noah story for theological agendas outside of God’s agenda is so old that it actually predates Moses writing down the Noah story in Genesis (the story would have been passed by word of mouth until it was written down). Moses wrote about Noah generations after the fact, and by that time just about every culture and religious group from the Ancient Near East had a flood story that interpreted a cataclysmic flood according to their theological convictions (eg the Gilgamesh Epic).

And when it comes to the story of Noah itself – Jewish, Islamic, and Christian interpreters all understand and tell the story of Noah (and indeed the entire Old Testament) differently. We understand that the story of Noah helps us understand the story of Jesus. And we should, as Christians, be thankful that Aronofsky chose the story we’re conversant with, so that we can converse with it. This could easily be Gilgamesh.

You don’t have to like a movie for it to be a good or useful movie. You don’t have to agree with the worldview a movie presents in order to enjoy the movie and think it is worth engaging with. You don’t have to dismiss a movie simply because it challenges your view of the world. If we only want to view and consume art and media that conforms to our own view of the world we’re very quickly signing up for a propaganda campaign.

INTERPRETING TEXTS (LIKE NOAH) WITH THE WRITER IN MIND

If we approach Noah as though Aronofsky’s decision to choose a story we like means it’s our story to control, and he has to tell it the way we like, that’s a pretty interesting and disconnected understanding of how texts work in our world.

Writers have always adapted stories to suit their own purposes, according to their creative agendas to put forward a worldview. That’s what Aronofsky is doing here, he told The Atlantic:

“For me, there’s a big discussion about dominion and stewardship. There’s this contradiction [between the two], some would say, in the Bible, but it doesn’t have to be a contradiction. It can work together. The thing is, we have clearly taken dominion over the planet. We’ve fulfilled that. But have we been good stewards?

Leviticus, also in the Bible, talks about how every seventh year we’re supposed to give the land a rest. When’s the last time our land has gotten a rest? We’re way overdue for that jubilee. And I think that’s what I want. That’s why I made the film. For that reason.”

He told Christianity Today that he is responding to and engaging with the text in a manner consistent with his background.

“Within our tradition, being Jews—a long tradition of thousands of years of people writing commentary on the biblical story—there isn’t anything we’re doing that’s out of line or out of sync, but within that, you don’t want to contradict what’s there. In all the midrash tradition, the text is what the text is. The text exists and is truth and the word and the final authority. But how you decide to interpret it, you can open up your imagination to be inspired by it.”

I went in to the movie expecting to be confronted with a radical environmental agenda – but Noah critiques the radical environmentalism of its protagonist as much as the pillaging of the environment he confronts.

I left thankful that the Christian God isn’t a standoffish God, like the God of Noah, he doesn’t leave people wondering about how they can be saved, or what he wants them to do, interpreting signs and following dreams – but that he got his hands dirty in order to rescue people, that he revealed himself and his character progressively through the Old Testament and then ultimately in Jesus coming into the world, dying for the world – to fix the broken human condition – in a simultaneous act of judgment and mercy. Aronofsky got that paradox right. We felt the weight of it, from Noah and his family’s perspective, as he travelled the narrative arc of restoration of relationships, broken relationships, punishment, and redemption of relationship that drives the Old Testament. This perspective enabled us to feel the emotions of a human on sidelines watching on, and the weight of being an agent in the arc, while as judgment falls on people no more or less deserving of it than ourselves. It wasn’t that Noah’s heart was any different to those around him, it too was darkened by sin.

I left the movie feeling enriched for having seen it – even with the schlocky rock monster/fallen angels, and the narrative liberties Aronofsky took to further his own agenda – particularly leaving two of Noah’s sons wifeless, and the third with a barren wife (who – spoiler alert – miraculously conceives, which, surprisingly is a nice tie in with the OT narrative and with the miraculous birth of Jesus).

USING NOAH AS A TEXT, AS CHRISTIANS

For Noah to be useful you don’t even have to use it to have conversations with your friends, colleagues, and family who aren’t familiar with the story or who don’t believe in God – Noah is useful because it challenges us to reflect on the God we believe in, the God who takes sin so seriously he wipes out a planet full of people, we need to remember, despite Noah, that the Christian God does not stand back from the disaster of the human condition, but enters the fray to rescue people at great cost to himself.

The Christian God is not the God of Noah. But the God of Noah will help us think about who the true God is, and who we are as followers of the true God.

People won’t take us seriously as Christians – people who are defined by our understanding of a significant text – if we continue to read culture and media with an essentially illiterate interpretive approach. We can’t interpret cultural texts from other worldviews while ignoring things like genre (this is a Hollywood movie from an art house director, trying his hand at an epic, not a Christian puff piece) and context (the author of this piece is not claiming to present your views or your understanding of the story of Noah). Too many Christian reviews floating around the web don’t make those two connections.

We won’t just look disengaged from the people and culture around us, but we will be disengaged if we continue act as the entitled kid in the playground who wants the world addressed on our own terms and who will take our ball and go home if it isn’t.

We rightly get annoyed when people bring a foreign interpretive approach to our text – the Bible – and tell us what we should think… and we could rightly get annoyed if Noah was presented as an accurate rendition of the Biblical story… but it’s not. Noah is a movie. It’s based on a wide variety of source texts including the extra-Biblical Book of Enoch and the Midrashic interpretive traditions (where the crazy rock creatures, The Watchers come from – though their rockiness is an invention). Aronofsky’s presentation of the story, while it takes certain liberties with the narrative, is incredibly theologically rich, and while its aesthetic won’t be everybody’s cup of tea, I left the cinema feeling confronted about the depths of human sinfulness, challenged to think about how we should be looking after God’s creation, and struggling with the enormity of God’s judgment and its cost.

If we want to follow the examples of the writers of the Bible – and of Jesus who became a human medium to step into the muck of creation to communicate God’s rescue plan to us – then we need to be prepared to engage with the culture around us, and the worldviews that we don’t agree with, in order to connect the Gospel with the world we live in.

Engaging with, critiquing, and rewriting secular texts and stories in order to present God’s plan of salvation is also as old as the Old Testament. The Bible is full of appropriations of Ancient Near Eastern traditions corrected to point people to the true and living God – we don’t have any textual evidence to suggest that Egyptian sages got up in arms about the inclusion of Egyptian proverbs in Solomon’s compendium of Proverbs that are presented in a framework that tells people that true wisdom comes from fearing Israel’s God. So why are we indignant when people use our source material?

ENGAGING WITH NOAH’S THEOLOGY

This is a telling of the Noah story worth engaging with, not just dismissing, even though it’s a problematic telling of the story (partly just because of the rock monsters). It is richly presented, with sensitivity to the array of source material and some nice narrative driven imagination around some of the details we’re not given in the narrative – like where the wood came from, how God called the animals to the ark, and how they got the animals not to kill each other on the ark) – especially around the Eden motif. It explores big themes surrounding who God is, who we are, what justice, mercy, and righteousness look like, and ethics, especially environmental ethics.

Noah gets plenty of stuff wrong, and it takes liberties with the Biblical story to present another story – but it is a theologically rich and challenging story that uses Biblical themes in a stimulating way. Here are some of the themes I particularly enjoyed… Just beware, this contains serious spoilers…

WHAT DOES IT MEAN TO “BE A (HU)MAN?”

The question of what it means to “be a man,” or be human, is one of the interesting threads carrying the narrative, and, in a nice homage to chiastic Jewish story telling (a chiasm is like a hamburger layers that are paired around other layers on the inside) – it opens and closes the narrative. The question is posed at the beginning and only answered properly at the end. The story starts with Noah’s dad sitting Noah down for the chat, to tell him about humanity’s proper place in God’s world. Only the chat is interrupted when (spoiler alert) the film’s villain caves Noah’s dad’s head in while his shocked son looks on from a hiding spot behind a rock. Noah’s dad is killed in the name of pillaging the planet by Tubal-Cain. As a result, Noah is left with no real understanding of humanity’s place in creation, and a serious chip on the shoulder when it comes to protecting the environment.

Flash forward a few years and he won’t even let his son pick a flower, he murders three men for killing one dog, and he has a theological conviction that animals are innocent and humans are evil and corrupt. He has one shaky anthropology.

Even Tubal-Cain knows humans are made in God’s image, though he thinks this means exercising dominion and trashing the place in pursuit of power. When Noah’s son Ham sticks a knife into his armpit, killing him, Tubal-Cain whispers “now you are a man.” This is an understanding of humanity built on the foundation of our post-Eden brokenness, and a weird picture of God as capricious, with no real connection to our created role.

Then God said, “Let us make mankind in our image, in our likeness, so that they may rule over the fish in the sea and the birds in the sky, over the livestock and all the wild animals, and over all the creatures that move along the ground.”

So God created mankind in his own image,

in the image of God he created them;

male and female he created them.

God blessed them and said to them, “Be fruitful and increase in number; fill the earth and subdue it. Rule over the fish in the sea and the birds in the sky and over every living creature that moves on the ground.” – Genesis 1:26-28

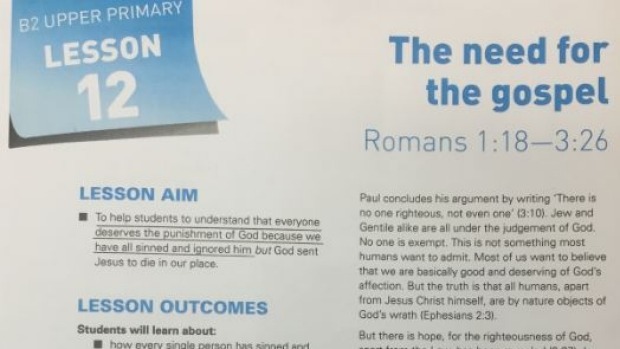

That’s what we were meant to be – but human nature in Noah’s day – as described in Genesis 6 – is a pretty messed up.

“The Lord saw how great the wickedness of the human race had become on the earth, and that every inclination of the thoughts of the human heart was only evil all the time. The Lord regretted that he had made human beings on the earth, and his heart was deeply troubled.” – Genesis 6:5

This is a theme Aronofsky and his co-writer say they were exploring. Deliberately.

“What intrigued me and Ari was that Noah is the fourth story in the Bible. You have creation, original sin, the first murder, and then it jumps forward and everything’s terrible, and God wants to start over again. What was clear to us was that Noah is a descendant of original sin. There are three sons, and he’s a descendant of Seth, so his ancestors are Adam and Eve, so he has that inside him. That brought to us this weird question: Why restart if that possibility [of being sinful] is still there? Man still has the possibility of being tempted.

AH: Especially because you finish reading Noah and all the wicked people have been wiped out, and one family survived, and you flip the page and it’s Babel. So it immediately raises the question, what does that mean? If you look at the context of the story within the Bible, what is that trying to say about the sinfulness and wickedness within us? That was what we had to explore, not the good guys and the bad guys, but both the good and the bad within us.”

There’s a great scene in the movie extrapolating what happened between Cain and Abel into modern times, modern killing – the darkness of the human heart is universal. This movie nails sin. There’s another great scene where Noah is in the middle of a clamouring, angry, mob and he sees a picture of himself participating in the depravity. He’s struck by the realisation that he’s evil too. As a result he becomes committed to wiping humanity out and giving the animals a fresh start. He tells the creation story to his family while they’re locked in the boat – and he stops before the creation of man, suggesting that’s where God hit perfection, the pinnacle, paradise – with man something of an afterthought that quickly trashed the joint. This is fiction – it’s not in the Bible. It’s also not the view the movie presents (even though it is presented in the movie). The movie demonstrates this is an inaccurate view. We’re meant to get that Noah is getting it wrong.

In the Bible it’s when God creates man that the world is “very good” not just “good,” in the Bible it’s clear that human life is meant to be preserved by the ark (there are more animals that are good for eating taken on board than the other types of animals). We’re meant to get that Noah is wrong about this, in the movie, that it’s the result of Noah’s theologically broken understanding of humanity’s place in the world. We’re meant to get this when the women in his life speak reason, compassion, and mercy to him. We’re meant to get this when we see his understanding of humanity is righted as he first confronts his heart’s capacity for love when he meets his new twin granddaughters. We’re meant to get it when at the end of movie (and the closing of the chiasm) he tells his children and grandchildren that being human means being God’s image bearers, stewarding creation.

Some people have suggested that we’re meant to see Noah rejecting the harsh approach of ‘the Creator’ in his love-fuelled epiphany, but we’ve earlier been told that God doesn’t speak in the way Noah keeps expecting him to – he speaks in “a way we will understand” – he speaks through people, circumstances, and through qualities that are in line with his plans and character. Every time Noah is about to do something stupid, or things look dire, he’s delivered by providential timing. Even if he’s an oblivious idiot, hell-bent on self-destruction the self-destruction is interrupted by circumstances – like the ark crashing into the mountain. Though he feels like he’s left stranded and unaware of what God wants, he is riding the waves of God’s plan from start to finish. The God of Noah is bigger than the characters in the movie appreciate.

What’s nice about this theme is that it lays a platform for Christians to talk about what it means to be human. It gives us a chance to point to Jesus, the “image of the invisible God” (Col 1:15) who demonstrates what sacrificial love for God and for others looks like and renews our humanity by giving us the changed hearts the Old Testament promises and anticipates. The only way out of the darkness of our hearts is to turn to God, we can’t just love our way out of trouble and into goodness. Noah’s quest to save humanity is ultimately doomed – as we see in the very next chapter of the Bible. It’s only when God steps in to the picture that things can change.

WHAT IS THE ‘GOOD LIFE’ IN GOD’S WORLD? AND HOW DO WE KNOW?

Every pre-flood character is operating with a shaky understanding of humanity’s relationship to God and, as a result, in how to live in the world and care for the environment. The champions of the film’s two human sides – the descendants of Cain (Tubal-Cain) and of Seth (Noah) have competing ideas from competing extremes on the spectrum.

Tubal-Cain thinks following God – as an image-bearer – means digging up all the precious resources to dominate the planet.

Noah thinks the environment is more important than human life and that it’s right to wipe out humans in order to give the environment a second chance.

Their views are clearly flawed. It’s not just left up to us, the audience, to figure that out. The idea that it is morally good to kill two newborn children so that humanity can die out is clearly repugnant, as is the idea that having dominion means trashing the planet. Adam and Eve were given a job in the Garden of Eden – to cultivate and keep the garden, presumably to extend its amazing life-giving presence over the whole planet. They were also to be fruitful and multiply. This is the tension – between dominion and stewardship – that drove Aronofsky to make the movie. He’s not an environmental crazy person just because his protaganist is, and Noah’s views change and grow through the movie.

Noah is not the environmental propaganda film some have painted it to be.

And even its call to care for the environment has theological merit. Those who would follow the God of the Bible have a responsibility to care for the creation God left us to operate in. From the preceding chapters in the Biblical narrative it is clear that humans had an environmental responsibility, and if they are being “only evil all the time” you can be certain this includes mistreating the environment.

Both Noah and Tubal-Cain have wrong views of man, of the world and of God. Both struggle to figure out how God reveals himself, and are given to looking for mystical dreams, drug induced revelation, or the sky splitting open, to figure out what God wants of them. Both expect a God who is so distant he is essentially absent. Their creator is essentially a ‘demiurge’ – a small god who exists within and is confined by creation, a small and mechanistic deity that is only present if he is obvious. The god Noah and Tubal-Cain are looking for is the sort of god that the New Atheists think Christians follow, and the sort of God they’d stand up and take notice of if he’d only fling lightning bolts at their heads or rearrange the stars to write them a message.

In a bit of a contradiction, Noah’s God is both distant and about to step in with an apocalyptic intervention because he’s not happy with what’s happening in his world. This makes Noah’s God seem petty and vindictive. Aloof but angry. The Watchers – the crazy rock monsters – don’t help here, their inclusion paints Noah’s god as petty and small-minded. It’s only Methuselah – and later Noah’s wife, Naameh, and daughter-in-law, Na-El – who have a view of God working through and authoring events, who expect God to be operating and revealing himself through the ordinary and mundane – “speaking to people in a way they will understand” as Methuselah puts it. It’s these three who come closest to seeing God operating relationally through judgment and mercy – not being a detached monster. Noah gets there in the end. But the journey isn’t pretty.

Noah’s descent into craziness (in the film) involves a movement from complete trust in God’s providence (he tells Ham that God will provide the wife he desires as he provided the wood for the ark – in a nice hat tip to Abraham’s answer to Isaac when he asks where the sheep to be sacrificed is a little later on), to an inability to recognise that providence even when it appears miraculously through the pregnancy of his apparently barren daughter in law. It’s clear that Noah stops relating to, and listening to God, when he stops seeing his provision of salvation as a form of revelation of his plan.

It’s only when we see God as very (infinitely) big, and outside of creation – supplying life and breath and being to the universe (Acts 17), while also being very (omnipotently and omnipresently) engaged with what’s going on in the world, especially with what’s going on in the human heart, that we can understand how God might be working in our lives without us noticing, or without us hearing the blaring trumpets in the sky heralding his every move.

It’s only when we see God as deeply invested in the fate of humanity and the planet that we can even begin to appreciate the motivations behind the flood, and Noah goes some way towards asking and answering that question in a real way.

GOD’S DEEP INVESTMENT INTO HUMANITY IS DISPLAYED MOST VIVIDLY AT THE CROSS OF JESUS.

The good life is a life connected to God, the giver of life. It’s a life lived in the light of his revelation to us, in a relationship with him. God is not distant. The Christian God is the God who comes near. The God who speaks. Who speaks to create. Who speaks to reveal. Who spoke to Noah (in the book version) with detailed instructions. Who speaks through texts people understand, using genres they can engage with – and who then reveals himself in Jesus, his word made flesh (John 1:1). The Christian God is not petty, small-minded, and vindictive, he doesn’t stand back from the problem of sin, but gets involved. He was prepared to become nothing in the person of Jesus, prepared to become human, prepared to sacrifice his son to save the world (which makes the horror Noah feels at that idea even more poignant – God went to lengths we can’t imagine). Jesus also provides the guide to living the good life – a life lived for the sake of others, to reconnect them with God. We know what the good life is, because we see it in Jesus – the true image bearer.

“In your relationships with one another, have the same mindset as Christ Jesus:

Who, being in very nature God, did not consider equality with God something to be used to his own advantage; rather, he made himself nothing by taking the very nature of a servant, being made in human likeness. And being found in appearance as a man, he humbled himself by becoming obedient to death— even death on a cross!” – Philippians 2:5-8

THE DEPTH OF SIN AND COST OF JUDGMENT: BOTH JUSTICE AND MERCY

One thing the movie Noah belts out of the park is the picture of the human condition. I don’t think I’ve seen any movie that deliberately captures the darkness of the human heart like this one does, or that thinks a massive reboot of the human race is a fathomable response to this sort of darkness, the movie is sympathetic to the cost involved in carrying out judgment like this. The anguish on Noah’s face as people – even evil people – are erased from the earth and his dejected response when they finally hit land is a really helpful picture of how broken humans should respond to God’s judgment when we’re, through no merit of our own, recipients of his saving mercy. We should be horrified by the fruits of sin – the death it brings into the world, and by the cost of sin.

This part of The Atlantic’s interview with Aronofsky is profound.

“We constructed an entire film around that decision. The moment that it “grieved Him in his heart to destroy creation,” is, for me, the high dramatic moment in the story. Because think about it: It’s the fourth story in the Bible. You go from creation to original sin to the first murder and then time jumps to when everything is messed up. The world is wicked. Wickedness is in all of our thoughts. Violence against man and against the planet.

And so it was so bad that He decides that He is going to destroy everything and destroy this creation. So what we decided to do was to align Noah with that character arc and give Noah that understanding: He understands what man has done, he wants justice, and, over the course of the film, learns mercy. What’s nice about that is that is how I think Thomas Aquinas defined righteousness: a balance of justice and mercy.

Maybe what made Noah righteous was that he mirrored, in some sense, God’s own heart about what was happening?

Sure. That’s another way of looking at it. And we completely connected that. Because really, Noah just follows whatever God tells him to do. So that led us to believe that maybe they were aligned, emotionally, you know? And that paid off for us when you get to the end of the story and [Noah] gets drunk… What do we do with this? How do we connect this with this understanding? For me, it was obvious that it was connected to survivor’s guilt or some kind of guilt about doing something wrong.”

I spent most of the latter half of the movie pretty angry with Aronofsky’s Noah, because he didn’t seem to have any understanding of mercy whatsoever. This was a fruit of his anaemic understanding of humanity (as something like a cancer), a result of a poor understanding of God (as someone distant and dispassionate) and of creation (as paradise ruined and innocence lost). This cold-hearted pig-headed lack of mercy made me want the story to end with a twist, where Noah died and everyone lived happily ever after, because that seemed the just response for people having to put up with Noah on the ark for so long. But in a nice picture of sacrificial love – it’s the daughter in law who reaches out to Noah to redeem him, to bring him back from the wine-addled abyss he found himself in. The daughter in law who he had terrorised, whose children he held at knife point in his pursuit of justice. She restores Noah’s humanity, she mends his broken understanding of how God might reveal himself, and she invites him to come back home because God is a “God of justice, mercy, and second chances.”

Because Noah treats sin as a big deal, it treats salvation as a big deal, and as a result, sees the cost of justice and salvation being carried out simultaneously as carrying an incredibly heavy toll. Noah is at the point of emotional breakdown on the ark, just as the last sight of land disappears – and he has the breakdown when they finally land. Pursuing justice and offering merciful salvation at the same time is costly.

PARADISE LOST – THE RETURN TO EDEN

My favourite motif in the movie is the use of Eden. The theme of paradise lost, and seeing Noah’s journey as an effort to recreate Eden, an effort that everyone – from Aronofsky in his interviews to Noah in his character – knows is doomed to fail because of the mess in the human heart.

Eden becomes a vehicle for the film’s environmental agenda. Noah’s Eden is a place where humans live in harmony with nature – stewarding it. Where humanity in some sense, exists for the garden, not the garden for humanity. Noah spends a significant part of the movie believing that humans should not be present in the garden at all. Pushing us a few steps towards a return to the environmental paradise is the ethical goal, or end, of the text.

Aronofsky does some really fun stuff with Eden. The ark is made from wood from a forest created by a seed from Eden that Methuselah has carried around with him waiting for the right time. When the forest springs up, five waterways appear and spread around the planet, inviting the animals to the ark – back to Eden. There is certainly an element of ‘recreation’ going on in the Noah story in the Bible. Noah is a new Adam. Adam named the animals and ruled over them, Noah protects the animals carrying them in an Edenic sort of boat – a wooden replica of Eden’s ‘tree of life’ – delivering salvation in the midst of God’s judgment. There’s a nice sensitivity in Noah to the place of Eden in the Old Testament. Eden imagery appears everywhere in the Old Testament – in prophecies about what it to come when God restores hearts, and in the interior design of the Temple.

What really interests me is that the Bible already has a concept for a seed surviving out of Eden. And it’s not about the trees. It’s about humanity. We lose this a little bit in most of our English translations – but in Genesis 3:15, where God provides a glimmer of hope about the future of humanity and the future of Satan amidst the cursing and expelling Adam and Eve from the Garden, there’s the launch of a thread that works its way through the Bible all the way to Jesus – there’s a seed that we follow from here on in. Passed on from generation to generation – it’s a theme in Genesis. The NASB chooses to use the literal “seed” rather than offspring – here’s what it says:

“And I will put enmity Between you and the woman, And between your seed and her seed; He shall bruise you on the head, And you shall bruise him on the heel.” – Genesis 3:15, NASB

Interestingly, Jewish and Christian interpreters read this seed line very differently. For Christians, it’s a very early promise that God will intervene with a messiah. It’s a glimmer of hope amidst the darkness of Genesis 3 – the breaking of our hearts and the breakdown of our created relationship with the Creator.

If Aronofsky’s Noah understood the seed of Eden as human he’d have had a very different view about the purpose of the ark (one that was more consistent with the Biblical narrative). And it’s a helpful way to engage with the film’s environmental agenda – it helps us order the relationship between humanity and creation rightly. We are to steward creation so that it helps us do what we were created to do – exercise dominion and carry God’s image around his creation. As Christians, who are people being recreated in the image of Jesus, our divine mandate looks more like the Great Commission – we’re to steward creation in a way that helps us help people reconnect with God through Jesus. Compare Genesis 1:28 with Matthew 28:19-20…

“Be fruitful and increase in number; fill the earth and subdue it. Rule over the fish in the sea and the birds in the sky and over every living creature that moves on the ground.” – Genesis 1:28

We’re told to fill the earth with God’s image bearers in Genesis 1. And then in Matthew we’re told to make disciples – people being transformed into the image of Jesus, all over the world…

“Therefore go and make disciples of all nations, baptising them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teaching them to obey everything I have commanded you. And surely I am with you always, to the very end of the age.” – Matthew 28:19-20

We’re to “subdue the world” in this new commission by connecting them with Jesus and the Creator (baptising them in the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit) and teaching people to obey Jesus’ commands – commands Jesus sums up a few chapters earlier in Matthew. This is all about the restoration of our humanity and the restoration of our relationship with the Creator.

“And he said to him, “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind. This is the great and first commandment. And a second is like it: You shall love your neighbour as yourself. On these two commandments depend all the Law and the Prophets.”

Loving God with all our hearts is something the Old Testament demonstrates is impossible – it’s the complete opposite to God’s diagnosis of the human heart just before the flood (Genesis 6:5), and this restoration of human heart’s is also tied to the restoration of the planet. This is what Christianity offers to the environmental agenda – hope that when the world is one day populated only by people with transformed hearts, it too will be restored.

“For the creation waits in eager expectation for the children of God to be revealed. For the creation was subjected to frustration, not by its own choice, but by the will of the one who subjected it, in hope 21 that the creation itself will be liberated from its bondage to decay and brought into the freedom and glory of the children of God.

We know that the whole creation has been groaning as in the pains of childbirth right up to the present time. Not only so, but we ourselves, who have the firstfruits of the Spirit, groan inwardly as we wait eagerly for our adoption to sonship, the redemption of our bodies.” – Romans 8:19-23

While this waiting is going on, God is transforming hearts and transforming people into a new image – the image of Jesus – by his Spirit.

And we know that in all things God works for the good of those who love him, who have been called according to his purpose. For those God foreknew he also predestined to be conformed to the image of his Son, that he might be the firstborn among many brothers and sisters. And those he predestined, he also called; those he called, he also justified; those he justified, he also glorified. – Romans 8:28-30

God is profoundly interested in this “seed” from Eden continuing, and coming back to what it was like in Eden, being restored to Eden like status – a relationship with the Creator.

In order to return humanity to Eden, God does use something like the tree of life, a new wooden vessel where salvation and judgment are played out. The cross. Where Jesus, the true seed of Adam – the true Adam. God’s image made flesh. Is crucified. Nailed to a tree that takes our curse and brings life in an amazing exchange. The cross is Noah’s Ark on steroids. It’s capable of carrying any human who turns to God back to Eden. Back to paradise. It shows the value God places on human life, the cost he’s prepared to pay in order to be the God of justice, mercy, and second chances.

A Jewish understanding of God as presented in Noah misses this vital piece of the picture – the vital piece where God steps in to the world, where God is not absent, still. We are not waiting for the Messiah to come. We are living in 2014AD. Counting the years since Jesus arrived. Our God is not silent and distant. He is not able to be understood as capricious or vindictive. He knows the cost of justice because he paid the price.

Aronofsky’s Noah prompted me to think through this aspect of God’s character, and God’s desire for us to steward creation well in order to connect people with Jesus, the giver of life, through the tree of life – the cross. If he’d told the story my way, that would’ve been amazing. I’d love for Darren Aronofsky to meet Jesus, and to understand the Noah story through his worldview, but in the mean time I’ll settle for appreciating the care and sensitivity he put in to telling his version of the story in a rich way.