How are we going to respond to the Secular Juggernaut? Here are some lessons from ancient and modern examples of life as exiles.

There’s been barrel loads of digital ink spilled in the last year or so on the question of whether the church is now in exile; culturally; and how helpful this is as a category for thinking about life and our witness in the world. Stephen McAlpine wasn’t the first to get the ball rolling, the Apostles Peter and Paul probably started it all a while back, and there are plenty of characters in the early church who piled in, but there is certainly a sense that if Christendom represented some sort of return from exile, we’re entering some new era in the life of the church and our relationship with the world and its powers, and even just its people, our neighbours. McAlpine called this Exile: Stage Two, and in that pivotal post suggested we should stop thinking of ourselves as being in Athens — a marketplace of ideas where we’ll get a hearing — and start thinking of ourselves as being in Babylon — where we’ll potentially be fed to lions. I liked what he said, but felt the paradigm was a little too OT exile focused and not enough a reflection of the sort of exile being experienced by God’s people around the time Jesus arrived on the scene. At the time I suggested Rome, not Babylon, the empire that executed our Lord, but that also presented an ultimate alternative vision for human flourishing to the Gospel — one built on power, prestige, wealth, and sexual liberation — is perhaps a better paradigm for us to be thinking in.

The church-as-exiles movement has continued rolling along in the last year and a half, and there have been plenty of landmark cases both here in Australia, and elsewhere in the western world for us to both notice the seismic shift in the world we live in especially with regards to the place so-called Christian values have in our social norms and laws, and to figure out how we’re going to respond to those shifts. We’ve had Safe Schools, and a continued debate on same sex marriage; we’ve, increasingly, been told that religious freedom is the greatest human right since sliced bread and something to be upheld at all costs, and often found that voicing traditional Christian views — those still reflected in our laws — is a form of bigotry (all our grandparents and most of our parents, it seems, are actually bigots when assessed by today’s values).

Somehow, in the midst of all this, Christians have been standing up in the public square to be speaking in favour of a bunch of created goods like marriage and freedom without really saying much at all about the creator, or his grand story of forgiveness, redemption and victory over death in Jesus. It’s like the public square is now a bonfire where we’re burning anything ‘Christian’ that looks off-trend, and it feels like life as exiles is mostly about trying to hold on to valuable furniture. Sometimes it feels like certain streams of Christianity are figuring out what furniture to toss on the fire in order to join the fun, rather than trying to douse the flames and call people to a better party.

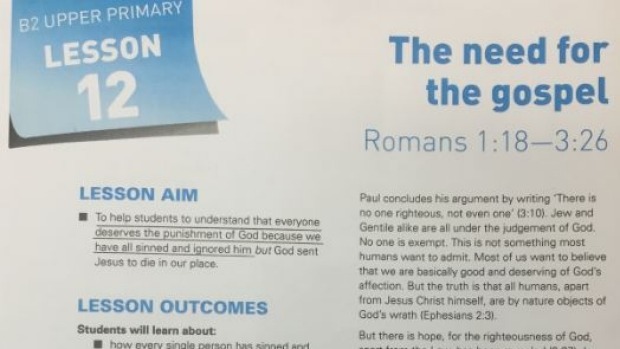

There is, at the heart of an understanding of who we are as Christians, a fundamental disconnect between how we see and live in the world, and how our neighbours do; a difference in the kingdom we belong to and the values and virtues we pursue. Like Israel before us, we’re called out of the world, by God, to be different. We’re by nature exiles in a profound sense, not put into exile by the world but by an exodus brought about as God rescued us; this brings us a totally different view of the world. As Paul puts it:

We do, however, speak a message of wisdom among the mature, but not the wisdom of this age or of the rulers of this age, who are coming to nothing. No, we declare God’s wisdom, a mystery that has been hidden and that God destined for our glory before time began. None of the rulers of this age understood it, for if they had, they would not have crucified the Lord of glory…

What we have received is not the spirit of the world, but the Spirit who is from God, so that we may understand what God has freely given us. This is what we speak, not in words taught us by human wisdom but in words taught by the Spirit, explaining spiritual realities with Spirit-taught words. The person without the Spirit does not accept the things that come from the Spirit of God but considers them foolishness, and cannot understand them because they are discerned only through the Spirit. — 1 Corinthians 2:6-8, 12-14

We are Mystique: Trying to figure out how to be ‘Mutant and Proud’

Life in our rapidly changing world can feel like we’re the mutants in the world of Marvel’s X-Men, trying to figure out exactly what to do with a super-power that feels a lot like being an unwelcome freak.

Do we let the world co-opt us to its agenda? Like Wolverine, who is signed up to the Weapon X program to serve the human ’empire’?

Do we adopt Magneto’s scorched earth strategy and attempt to forcibly mutate or eradicate those who would stand against us?

Take the ‘cure’ offered by the world — like the vaccination offered in X-Men: The Last Stand so we give up our power to become just like everyone else for the sake of our comfort and theirs?

Do we withdraw and hide and wait for a time when we’ll be welcome again? Or live undercover, like Beast desires with his serum — hide our mutation but keep our power, pretend there’s nothing different about us?

Or do we follow Charles Xavier who has a vision for a world where mutants and humans co-exist? Using our difference to serve the community, even as they try to crucify us for it?

The most interesting character in the X-Men franchise isn’t one of these people advocating one response or another, but Raven/Mystique whose shape-shifting ability would allow her to comfortably choose any of these options. Ironically in one timeline she’s shot with the ‘cure’ and abandoned by Magneto cause she’s not a mutant anymore… Throughout the different storylines, but perhaps especially in the new timeline stories, she’s pulled in different directions by each of these ‘leaders’ — Professor X, Magneto, and Beast — who each love her in their own way and desire their vision of the good life for her.

It’s a bit like the church is Mystique; we have the power to look just like everybody else, to hide, or to be proudly mutant and fight, or to use our power to love and save our enemies… we just have to decide which way we go.

What does it look like for us to be proud mutants where our mutation is shaped by our new DNA, the DNA that comes from being children of God, united with Christ, and being shaped by the Holy Spirit? What does it look like to be exiles because we’re different to a world around us that doesn’t like difference?

It’s not just the world of the X-Men that might help us grapple with how to live in a shifting world, but how Israel responded not to exile in Babylon as they hoped for a return to power (as we see it in the Prophets, and in characters like Daniel), but under Roman rule, where that return had failed. There are parallels in Jewish history for each of the paths taken by the protaganists in the X-Men franchise.

Weapon-X: The ‘Hellenisers’, Pharisees, and ‘if you can’t beat ’em, join em’ Option

Under Roman rule the easiest thing for the Jewish community to do was simply to, as much as possible, act Roman. To cuddle up to the empire and, as a result, be allowed the freedom to practice their religion so long as it didn’t upset the Imperial apple cart. Tertullian, a Christian guy writing in the late 2nd century described the status as Judaism in the empire as being a religio licita; a legal religion. Judaism enjoyed a privileged place in the empire — they didn’t have to physically bow the knee to Caesar, so long as they offered prayers for the emperor and empire in the Temple. Both Tertullian, and the Gospel writers, point out that this concession was largely symbolic; it was pretty clear who really ruled, and never clearer than in the battle between Caesar and Jesus that the arrival of God’s promised king represented.

The Sadducees went a step further than the Pharisees in that the Pharisees maintained a degree of difference, proudly, from the people around them. The Sadducees, it seems, were ‘hellenised’ — they took on the cultural and physical appearance of the Graeco-Roman world they lived in so they wouldn’t stand out. They were happy to deny spiritual and supernatural concepts like the resurrection of the dead — a concept the Greek world, especially the world of Greek philosophers (and the Areopagus in Athens is an example of this) found pretty laughable, but which even the Pharisees held on to. It made sense for them to conform because they didn’t believe anything particularly distinct anyway… They just wanted to look like everyone else, so they became like everyone else.

The Pharisees and Sadducees were so keen to hold on to their privileged place in society that they threw Jesus under the bus and joined Team Caesar, the equivalent of William Stryker’s Weapon X program, where mutants fought for the empire.

Then the chief priests and the Pharisees called a meeting of the Sanhedrin.

“What are we accomplishing?” they asked. “Here is this man performing many signs. If we let him go on like this, everyone will believe in him, and then the Romans will come and take away both our temple and our nation.” — John 11:47-48

This came to a head at the crucifixion, where it was pretty clear they weren’t separate any more…

From then on, Pilate tried to set Jesus free, but the Jewish leaders kept shouting, “If you let this man go, you are no friend of Caesar. Anyone who claims to be a king opposes Caesar.”

When Pilate heard this, he brought Jesus out and sat down on the judge’s seatat a place known as the Stone Pavement (which in Aramaic is Gabbatha). It was the day of Preparation of the Passover; it was about noon.

“Here is your king,” Pilate said to the Jews.

But they shouted, “Take him away! Take him away! Crucify him!”

“Shall I crucify your king?” Pilate asked.

“We have no king but Caesar,” the chief priests answered.

Finally Pilate handed him over to them to be crucified. — John 19:12-16

There’s an incredible temptation for us to do this in the church today, and plenty of people are doing just this. Going as far as the Pharisees in giving up any sense that the Lordship of Jesus requires anything other than totally bowing the knee to Caesar. Christians are told to pray for and honour those in authority and to be oriented towards living at peace, but not at the expense of citizenship in God’s kingdom (1 Timothy 2:1-2, Philippians 3:20, 1 Peter 2:11-17). We don’t want to repeat the mistakes of the Pharisees.

Tertullian doesn’t really want the empire to assume that Christians are a religio licita simply because we share a history with Israel, he has a different view for what life as exiles looks like that we will return to below…

“I have already declared the Christian religion to have its foundation in the most ancient of monuments, the sacred writings of the Jews; and yet many among you well know us to be a novel sect risen up in the reign of Tiberius, and we ourselves confess the charge; and because you should not take umbrage that we shelter ourselves only under the venerable pretext of this old religion, which is tolerated among you, and because we differ from them, not only in point of age, but also in the observation of meats, festivals, circumcision, etc., nor communicate with them so much as in name, all which seems to look very odd if we are servants of the same God as the Jews” — Tertullian, Apology, XXI

He’s also not so keen to cuddle up to the empire, as we’ll see below.

Brotherhood of Mutants: The Maccabees, Zealots, and the ‘Culture Wars’ Option

Magneto: This society won’t accept us. We form our own. The humans have played their hand, now we get ready to play ours. Who’s with me?

Magneto: [to Mystique] No more hiding.

Professor Charles Xavier: [to Mystique] Go with him. It’s what you want.Raven Darkholme: And one more thing. BEAST!

[Raven places free her hand on her chest]

Raven Darkholme: Mutant and Proud! — X-Men: First Class

Magneto’s goal is to use power — his power — to win a victory for his people; to take the ascendancy in the culture wars so that his people rule everyone else. In the first X-Men movie, Magneto wants to use a machine to turn everyone into mutants; like it or not. In others, like First Class, he simply wants to win freedom for mutants to be mutants, but he wants to do so using power. This isn’t so different from the Maccabees in the second and first centuries BC.

Before the Romans took hold of Israel there was a period when they were under the rule of the Greeks and then the Seleucid Empire. Israel was in exile, and they didn’t love it. They staged a violent revolution, led by the Maccabees family. They were largely successful in reclaiming Judea, and tried to use military force to convert people to Judaism. They cleansed the temple and looked like they had things all together; until the Romans arrived and took over about 100 years later. The zealots picked up where they left off… they were around in Jesus’ day, but rather than fighting as an organised army, they were like ninjas… they launched stealth attacks on Romans and Roman sympathisers with sharp knives. But zealotry didn’t really work… the ‘live by the sword, die by the sword’ maxim proved true.

The equivalent these days is to act as a combatant in the culture wars; to take up your political sword (more often than not a keyboard) and attempt to use power to secure your desired outcome at the expense of those who disagree with you, rather than figuring out how to live at peace with one another. This option, if you’re successful, produces short term success but your opponent comes back at you holding a grudge, or people know what it takes to unseat you from power — they just have to use power against you. It didn’t work for the Maccabees as a long term strategy. It never works for Magneto. Plus, a pretty smart guy (Jesus) said those who live by the sword will die by the sword.

District X: Essenes/Qumran and the Benedict Option

This hasn’t happened in the X-Men movie universe yet; but in the comics, a collective of mutants form a community-apart-from-the-community called Mutant Town or District-X. A place for mutants to be proudly mutant; apart from the world. In Israel, under Roman rule (and a bit before), the Essenes formed counter-cultural communities who behaved in counter-cultural ways; there’s a good chance they authored the Dead Sea Scrolls and that they viewed the Hellenised Jews as compromisers and covenant breakers. Their communities-of-difference were designed to maintain the faith. Josephus writes pretty extensively about them… here’s a couple of quotes about their differences from the world around them:

“Whereas these men shun the pleasures as vice, they consider self-control and not succumbing to the passions virtue. And although there is among them a disdain for marriage, adopting the children of outsiders while they are still malleable enough for the lessons they regard them as family and instill in them their principles of character…

… these two things are matters of personal prerogative among them: [rendering] assistance and mercy. For helping those who are worthy, whenever they might need it, and also extending food to those who are in want are indeed left up to the individual; but in the case of the relatives, such distribution is not allowed to be done without [permission from] the managers. Of anger, just controllers; as for temper, able to contain it; of fidelity, masters; of peace, servants. And whereas everything spoken by them is more forceful than an oath, swearing itself they avoid, considering it worse than the false oath; for they declare to be already degraded one who is unworthy of belief without God.

The Essenes were basically a Jewish monastic movement. They withdrew from society — or formed a counter-society in order to not be tainted by the wider society, but also to serve it. One response to our present life-in-exile that seems to be gathering momentum is conservative pundit Rod Dreher’s Benedict Option, in a sense it’s Alasdair MacIntyre’s Benedict Option in that it comes from this paragraph in After Virtue. It seems to be both a new District-X/Essenes movement based on the order started by St Benedict at the decline of the Roman Empire; a monastic movement that focused very much on virtue formation in an alternate community. MacIntyre wrote:

“What matters at this stage is the construction of local forms of community within which civility and the intellectual and moral life can be sustained through the new dark ages which are already upon us. And if the tradition of the virtues was able to survive the horrors of the last dark ages, we are not entirely without grounds for hope. This time however the barbarians are not waiting beyond the frontiers; they have already been governing us for quite some time. And it is our lack of consciousness of this that constitutes part of our predicament. We are waiting not for a Godot, but for another—doubtless very different—St Benedict.” — Alasdair MacIntyre, After Virtue

This all sounds very ‘Essene’ or very ‘District-X’… Dreher is keen for Christians to take up this vision; rightly calling us to remove ourselves from being too caught up with earthly empires — not making the Pharisee/Sadducee mistake, and calling for an end to the culture wars where we’ve tried to do a Magneto/Maccabees to fight off the imperial regime of our day. There’s been quite a lot written about this stuff since Dreher first proposed it; and frankly, it’s confusing exactly how engaged or disengaged with the wider world those pushing this barrow want their communes to be. It’s like a Benedict Option can be anything along a spectrum from Amish to just being a distinctly different community within the community (namely, the church), where you’re focused on cultivating virtue by being different in practice. Very few people would want to disagree with that… But there are three things I think are worth thinking about when deciding if the Benedict Option is the way forward:

- Are we in pre-dark ages Rome or pre-Christian Rome?

- Is withdrawing actually effective, or when all the Christians turn their attention inwards does that actually hasten the decline.

- Is virtue formation a means to an end, an end in itself, or a fruit of a good life, such that virtues are the character produced by a life lived towards a particular telos or mission, rather than being the aim of our mission.

In X-Men terms — are mutants the best version of themselves if they go off to mutant school to participate in a bunch of skill-honing montages, or are they better off training in mutant school, while stepping out to use their powers for the sake of others (which has the effect of training and forming these mutants to an end more inline with what goodness looks like (‘mutant and proud’ maybe?).

Dreher reads the cultural landscape pretty well, I think, its just that his solutions are a bit pessimistic and his view of Christian mission and what the church is for is a little too inwards looking for my liking.

Over the past decade, especially in the struggle over same-sex marriage, some of my friends and allies among social and religious conservatives have called me a defeatist for my culture-war pessimism. I believe that pessimism today is simply realism, and that it is better for us to retreat strategically to a position that we are capable of defending. The cultural battlefield has changed far more than many of us realize…

If by “Christianity” we mean the philosophical and cultural framework setting the broad terms for engagement in American public life, Christianity is dead, and we Christians have killed it. We have allowed our children to be catechized by the culture and have produced an anesthetizing religion suited for little more than being a chaplaincy to the liberal individualistic order… This is not to endorse quietism. I don’t think we can afford to be disengaged from public and political life. But it is to advocate for a realistic understanding of where we stand as Christians in twenty-first-century America. Our prospects for living and acting in the public square as Christians are now quite limited. — Rod Dreher, Christian and Countercultural

I’m a little more hopeful than Dreher that if we were to get our house in order, in the church, we might ‘catechise the culture’ via the Gospel, rather than being losers in the worship wars. I think we can revive Christianity first by returning to the Gospel, not by withdrawing from the world then returning to the Gospel in isolation. In Dreher’s Benedict Option the benefit is primarily for the church and the Christian — with a long term potential benefit for those seeking to come in to these communities for some sort of ‘protection’ from the new dark ages.

These communities offer a way for believers to thicken Christian culture in a time of moral revolution and religious dissolution. And if they’re successful over time, they may impart their wisdom to outsiders who crave light in the postmodern darkness. — Rod Dreher, Benedict Option

“Benedict did not leave the world for the sake of saving it. He left the world for the sake of saving his own soul. He knew that to put himself in a position where he was open to the Holy Spirit required living life in a certain way, in community. Hence the monastery. The monastic calling is a special one given to a relative few men and women, but the principle that believers need a community, a culture, and a way of life to keep themselves open to the formative (re-formative) power of divine grace is true for all of us.” — Rod Dreher, The Benedict Option Still Stands

For most of us, though, that degree of commitment isn’t possible, even if it were desirable. Our Benedict Option will express itself within institutions—churches, schools, para-church organizations, and so forth—whose purpose is to keep orthodox Christianity alive in the hearts and minds of believers living as exiles in an ever more hostile culture… We need to teach ourselves and our children to desire Truth, Goodness, and Beauty, as preserved within our traditions, and to make that pursuit the focus of our moral imagination. This is not a lofty ideal, but a matter of intense practical urgency. We do not have time to waste in building our little platoons… There are no safe places to raise Christian kids in America other than the countercultural places we make for ourselves, together. If we do not form our consciences and the consciences of our children to be distinctly Christian and distinctly countercultural, even if that means some degree of intentional separation from the mainstream, we are not going to survive. — Rod Dreher, Christian and Countercultural

Dreher also published a sort of FAQ guide to the Benedict Option if you want to get your head around it a bit more. If Carl Trueman is your cup of tea (he’s often not mine), he’s written a few pieces worth considering about the Benedict Option including: The Rise of The Anti-Culture, and Eating Locusts Will Be Benedict Optional. If you really want to understand the Benedict Option you could do much worse than read this piece by Matthew Loftus. For those following the Worship Wars series of posts here, there’s also this from Dreher which quotes the reasons James K.A Smith doesn’t like the Benedict Option. Also, for what it’s worth, Stanley Hauerwas says MacIntyre regrets the Benedict line as he puts forward what I think is a better alternative. Another thing by Greg Forster points out that:

“The Benedict Option” is a phrase now so thoroughly jawed over that it effectively means whatever you want it to mean. No amount of effort by Rod Dreher to clarify what he means by it can prevent everyone else who is looking for something new from using it to mean whatever they happen to be fascinated by…The overarching problem, however, is the Benedict Option’s failure to love the unholy world. The holiness of the church has crowded out its divine mission.” — Greg Forster, The Benedict Option As Culture War

The thing about the Mutant Town project, and the real, historic, Essenes community, is that neither of them had a lasting impact on their world and neither of them had the desired effect on the people leaving the world. They were failures. Unless the preservation of scrolls in some jars is a success. There’s probably even more concern for us as Christians if we take Paul’s logic in 1 Corinthians 9-11:1 seriously — it seems that imitating Christ is about the desire to win some to the Gospel by becoming like them rather than them becoming like us, and that the key to holding on to the Gospel is actually holding out the Gospel. It may be that being Christlike and on mission with the Gospel (and thus habitually living out the Gospel story) is what will cultivate real virtue for us, not simply withdrawing and doing a bunch of Holy sacramental, discipline type stuff.

The X-Men: The Jesus option

Raven/Mystique: You know Charles, I use to think it’s gonna be you and me against the world. But no matter how BAD the world gets, you don’t wanna be against it do you? You want to be part of it. — X-Men: First Class

Raven: Get out of my head, Charles!

Charles Xavier: Raven, please do not make us the enemy today.

Raven: Look around you, we already are!

Charles Xavier: Not all of us, Raven. All you’ve done so far is save the lives of these men. You can show them a better path.

Hank McCoy: [to Xavier] Shut her down, Charles!

Charles Xavier: I’ve been trying to control you since the day we met, and look where that’s got us… everything that happens now is in your hands. I have faith in you, Raven. — X-Men: Days of Future Past

But what if we’re not in the Dark Ages at the end of the empire? What if we’re in first and second century Rome?

What if District-X was as bad an idea as the Brotherhood of Mutants and Professor-X’s X-Men actually have it right? What if the key to virtue formation, the church’s survival, and the salvation of the world actually lies in us fighting to save it by lying down our lives for the sake of others? Living as exiles but seeking the welfare of our place? Our enemies even? Imitating Christ. What if our job is to show a better path as part of the world; fully engaged, fully on mission to keep people alive.

What if Professor-X is basically Jesus (and Cerebro something like a mechanical version of the Holy Spirit)? And what if we’re formed as virtuous people by living out the mission given to us by Jesus for the sake of the hostile world that crucified him. How do these very clear instructions end up with the Benedict Option rather than with a team, or community, of people on mission?

“Whoever wants to be my disciple must deny themselves and take up their cross and follow me. For whoever wants to save their life will lose it, but whoever loses their life for me will find it. What good will it be for someone to gain the whole world, yet forfeit their soul? Or what can anyone give in exchange for their soul? — Matthew 16:24-26

“Therefore go and make disciples of all nations, baptising them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teaching them to obey everything I have commanded you. And surely I am with you always, to the very end of the age.” — Matthew 28:19-20

How does the Benedict Option (or any of the others) represent a life that extends Jesus’ mission into the world, where he became ‘God with us’ — present and engaged with a hostile culture; light coming into a darkness he knew was not going to receive him (John 1); how does it reflect this model of God’s engaged presence in the world that begins at the start of the Gospel and continues here in the Great Commission with the promise that he is with us?

What if it’s not the monastery we should be looking to for inspiration for how to handle the barbarians at the gate, but to the early church living amidst the barbarous Roman Empire which executed Jesus. Oh yeah. Christians building systems based on the halcyon days of the Roman Empire — as if the barbarians only came from outside are like those who think America or Australia were ever really Christian empires, who are more shocked than the rest at the secular juggernaut because it represents a greater loss of territory and influence. The world is yet to see a political empire built with Jesus as king. The church is yet to be anything other than a community of exiles; an alternate polis.

What if we should assume Christendom ended so long ago that what we’re dealing with isn’t a world about to enter the darkness, but a world that has been dark for so long it forgets what life really looks like? What if we’re not the church in Benedict’s day, but in the time where Jewish exiles were running around getting in to bed with the Romans, stabbing them with knives, or setting up communes only for Jesus, and then his church, to emerge as a real alternative kingdom so thoroughly engaged with life in the empire, from the margins, that the values of the Empire eventually turned upside down? What if an optimistic taking up our cross is the answer; if it virtue-formation looks more like martyrdom than life in a commune? What if the hope for the empire doesn’t lie in us pulling out in the face of hostility, but pitching in.

What if instead of looking at the Benedictine monks and their practices we looked to texts like Tertullian’s Apology and the ancient Epistle to Diognetus, to see how the early church — those exiles — responded to the Empire (and how this differed from the suite of Jewish exilic models in Rome). Is the Benedict Option really going to produce the sort of Christian who so relies on the truth of the Gospel that we stand in front of the secular juggernaut and say “bring it on, the Gospel will go further if you steamroll me…” Cause that’s what Tertullian said…

“And now, O worshipful judges, go on with your show of justice, and, believe me, you will be juster and juster still in the opinion of the people, the oftener you make them a sacrifice of Christians. Crucify, torture, condemn, grind us all to powder if you can ; your injustice is an illustrious proof of our innocence, and for the proof of this it is that God permits us to suffer; and by your late condemnation of a Christian woman to the lust of a pander, rather than the rage of a lion, you notoriously confess that such a pollution is more abhorred by a Christian than all the torments and deaths you can heap upon her. But do your worst, and rack your inventions for tortures for Christians—it is all to no purpose; you do but attract the world, and make it fall the more in love with our religion; the more you mow us down, the thicker we rise; the Christian blood you spill is like the seed you sow, it springs from the earth again, and fructifies the more.”

Is withdrawing into our own communities, ultimately for our own sake, really going to provide the sort of schooling in virtue that we need to love our enemies and lay down our lives for them? Is it going to produce communities whose engaged difference works for the good of the empire as it transforms one life at a time until our momentum is irresistible? Until the Gospel becomes a juggernaut with more momentum than the secular community trying to ram us? It has happened before, and the key wasn’t people pulling out of society that did it… it was a bunch of exiles living as citizens of a better kingdom, lives like those described in the Epistle to Diognetus an anonymous description of Christian community and beliefs from the late 2nd century:

“For the Christians are distinguished from other men neither by country, nor language, nor the customs which they observe. For they neither inhabit cities of their own, nor employ a peculiar form of speech, nor lead a life which is marked out by any singularity. The course of conduct which they follow has not been devised by any speculation or deliberation of inquisitive men; nor do they, like some, proclaim themselves the advocates of any merely human doctrines. But, inhabiting Greek as well as barbarian cities, according as the lot of each of them has determined, and following the customs of the natives in respect to clothing, food, and the rest of their ordinary conduct, they display to us their wonderful and confessedly striking method of life. They dwell in their own countries, but simply as sojourners. As citizens, they share in all things with others, and yet endure all things as if foreigners. Every foreign land is to them as their native country, and every land of their birth as a land of strangers. They marry, as do all [others]; they beget children; but they do not destroy their offspring. They have a common table, but not a common bed. They are in the flesh, but they do not live after the flesh. They pass their days on earth, but they are citizens of heaven. They obey the prescribed laws, and at the same time surpass the laws by their lives. They love all men, and are persecuted by all. They are unknown and condemned; they are put to death, and restored to life. They are poor, yet make many rich; they are in lack of all things, and yet abound in all; they are dishonoured, and yet in their very dishonour are glorified. They are evil spoken of, and yet are justified; they are reviled, and bless; they are insulted, and repay the insult with honour; they do good, yet are punished as evil-doers. When punished, they rejoice as if quickened into life; they are assailed by the Jews as foreigners, and are persecuted by the Greeks; yet those who hate them are unable to assign any reason for their hatred.”

This doesn’t sound Benedictine to me. But it sounds powerful. It sounds like Jesus.

What if the answer isn’t withdrawal into ‘communities of virtue’ outside the mainstream but being an alternative community desperate to love the mainstream with the Gospel where our virtue is shaped by our interactions with the world such that martyrdom of some sort — the practice of self-sacrifice and rejection with our eyes fixed on the greater kingdom we belong to — is our process of being formed as virtuous people. There’ll be a certain sort of rich, thick, loving, community that makes martyrdom more plausible — if the love of the church is more compelling than the love of the world — but this sort of monastic way of life, even if still engaged, is both too negative and pessimistic about our chance to change the empire (as we did in the past) and too disconnected from the way of life we’re called to imitate. Jesus did not live in a monastery but spent his time amongst friends and sinners. The way to save our own soul, to run our race and hold on to the Gospel is to hold the Gospel out to others. To love others at cost. To be prepared to lay down our lives to do so. The way to be virtuous is to be on mission, to be the church, as Hauerwas puts it (confusingly, Dreher says he’s on board with what Hauerwas says in this interview, which is one of the reasons everyone is so confused about exactly what the Benedict Option is):

“The church doesn’t have a mission. The church is mission. Our fundamental being is based on the presumption that we are witnesses to a Christ who is known only through witnesses. To be a witness means you bear the marks of Christ so that your life gives life to others. I can’t imagine Christians who are not fundamentally in mission as constitutive of their very being – because you don’t know who Christ is except by someone else telling you who Christ is. That’s the work of the Holy Spirit.

Therefore it is the task of Christians to embody the joy that comes from being made part of the body of Christ. That joy should be infectious and pull other people toward it. How many of us have actually asked another person to follow Christ? In my experience, far too few.”

If you’re going to be ‘mutant and proud,’ in exile, be the X-Men. They always win. The movies tell me so.

There’s a better story that tells me that putting my pride in Jesus, for the sake of my neighbours, is a better way to win, and a better way to be an exile.