“…The Lord God made all kinds of trees grow out of the ground—trees that were pleasing to the eye and good for food…” // GENESIS 2:9

For since the creation of the world God’s invisible qualities—his eternal power and divine nature—have been clearly seen, being understood from what has been made, so that people are without excuse. // ROMANS 1:20

God created Coffee. Coffee reveals something about God’s qualities. Coffee is good.

Coffee is proof that God loves us.

It’s an interesting premise. A great T-Shirt slogan. But does it hold up to scrutiny?

I think it does. Here’s an attempt to prove the premise. This is long. Don’t think of it as a long blog post, but rather, a short e-book. But, for the blog post types – here’s the summary.

////////////////////////////

Coffee is part of God’s good creation, God’s creation includes creativity and beauty – he made things of quality to be enjoyed, the purpose of this good world God created was to point people to him, and to reveal his goodness.

Coffee is also proof that we are fundamentally messy.

The way we drink coffee reveals that our hearts are diseased, and that this disease is because we don’t use the stuff God created for what he created it for. The way we consume coffee, and the narrative we surround it with, diagnoses our heart.

We consume coffee, and are consumed by it. We consume coffee, and as we consume it, we consume others and consume our world.

We worship coffee. We are tempted to find our identity in coffee – to use it as a point of pride – or to make it part of the way we control the world. We are addicts. Unable to function without a daily dose.

Whether you call it ‘instant’ (an abomination that literally causes desolation), or ‘specialty’ (where my preferences more naturally lie), you’re introducing a narrative to your consumption that reveals your idols.

On the ‘instant’ front: we trash God’s good creation and the people who work the land, to mass produce low quality crops that we then turn into a dehydrated, chemically-maimed, husk of its former self for our instant gratification. We want total deniability when it comes to process, but want it to fuel our addiction.

On the ‘specialty’ front: We’re obsessed with control. We spend all our time finding finicky details to tweak for the sake of one iota’s difference, while crafting a narrative for the humble bean that explains just how sophisticated we are as we sip it – even if this means treating people and the planet more ethically, we wear our ethics as a badge of pride and self-glorification.

We engage in what CS Lewis calls the ‘gluttony of delicacy’ and can spend our time and money pursuing a perfect coffee, which doesn’t exist. Chasing a taste of heaven only regarding the creator of heaven and earth as something of an Arthurian punch-line. The chief end of our quest for perfection. Yet. The closest we get to the ‘God Shot’ – the Holy Grail of coffee craftsmanship – the more we realise it is unattainable.

We’ve taken God’s good gift of coffee and turned it into an idol, but even when we’re not worshipping it – the best most God-directed coffee experiences are still a reminder of what we crave.

Our best experiences of coffee now involve fleeting moments, ephemeral visions of the future, a tantalising window between two worlds, where we pull a few wisps of heaven into a porcelain cup, and have them drift past our taste buds into oblivion. They can’t be savoured for long because they are vapour. There, and then gone. Such momentary bliss is a reminder that we are not yet home. That the world God created has been frustrated by humanity’s choice – corporately, and individually – rejecting him and choosing to use the things he made the wrong way.

This ‘God Shot’, and what we do with coffee, is a simultaneous testimony to our limits, our brokenness, and God’s goodness.

/////////////////////

WHAT IS THE GOD SHOT

“It is a homage to God in a way because when someone talks about a God Shot, it is something so special, so unique, so perfect, it’s almost as if God Himself has blessed it.”

// Mark Prince, coffeegeek.com, ‘Defining what is the God Shot,’ 2002

What is the God Shot? You could do worse than reading this 12 year old attempt at a definition from Mark Prince. It’s hard to describe exactly what separates the God Shot from the great shot. There is a certain quality that lingers. That you identify when you find it, and that tugs at the edge of your palate when you don’t. The God Shot has a certain Je ne sais quoi about it that one can’t really begin to describe without dipping into foreign tongues to borrow words. It’s a picture with colours beyond the average spectrum.

Perhaps it’s like asking someone to imagine a blue yellow that isn’t green – our heads can conceive of such a fantastical construction – but picturing it is beyond us.

This is the God Shot. It brings impossibilities together. It is paradox in a cup. Or, as Mark Prince puts it while trying to find words…

“…the God Shot is the ristretto shot maximized to the point of achieving something that David Schomer (of Espresso Vivace) and many other espresso purists before him have sought: coffee that tastes as good as fresh roasted coffee smells.

This is the fleeting thing. It really is.”

// Mark Prince, coffeegeek.com

Specialty coffee tasters describe coffee with all sorts of ‘tasting notes’ – something akin to the things you’ll read on the label of a bottle of wine. There’s a tasting wheel that invites people who spend a lifetime honing their senses of taste and smell to describe the flavours and aromas of coffee – and the sides of the wheel very rarely meet. The God Shot brings them together.

Image Source: coffeesnobs.com.au

Here’s how to spot a God Shot in the wild… it’s a multisensory thing…

“The God Shot is a double ristretto shot that looks special from the moment it starts slurping down from the portafilter spouts. The colour of the streams is always a dark rust-red colour, and often a sense of tiger striping, with alternating lines of lighter rust with darker rust, can be seen. In the cup, the shot is 100% crema from the get go right up until the end of the pour, and the black nectar starts to form as you complete the shot. It can take up to 30 seconds or longer for the crema to settle in the top third of the cup, leaving the bottom two thirds an opaque black. The top of the crema is quite often a dark ruby rust color with no traces of over extraction (blond or beige spots), but often something called tiger-mottling, or specks of darker spots where the intense, highly concentrated colloids and flavours of the espresso draw show themselves – these are the barely-solubles that made it to the cup.

The aromas as you lift the cup to your nose almost overpower with the intense, pure smell of what the roasted and ground coffee smelled like moments before. As you swirl the shot to release even more aromas, the true God Shot will almost overwhelm you. Then it comes time for the first sip. You’ll know at this moment, if you didn’t already, this was something unique – the mouthfeel is beyond almost anything you’ve sampled before – the aromas, tastes, colloids, flavours, you name it, they all coat the tongue and seem to constantly hit the perfect notes on all four major taste areas of your tongue. They compete with each other, but always seem to compliment the areas of sweet, sour, bitter and sharp on the tongue.

As you swallow the shot, the back of your mouth and throat get the final joy – the espresso coats this part of your mouth and doesn’t want to give up. Where a normal espresso shot may leave bitters and an unpleasant tang in the throat, the God Shot gives such an amazing sensation of mild bitters and sweets that it is almost as if your mouth doesn’t want to lose this sensation – it wants to keep it around for a while.”

// Mark Prince, coffeegeek.com, ‘Defining what is the God Shot’

MY QUEST FOR THE GOD SHOT

Of the perhaps six thousand coffees I’ve consumed in the last eight years (at a rate of two a day, which is conservative)- this is when my chemical romance with C8H10N4O2 truly blossomed (it’s not really about the drug though – the effect of caffeine gets in the way of the consumption of delicious coffee as far as I’m concerned) – there are around six coffees that I remember – and salivate over just a little bit – six that I experienced as ‘God Shots’ – purists would say that by adding milk I’ve adulterated the untamed beauty of the espresso, but milk, too, is a gift from God to be enjoyed. And the creative coupling of milk and coffee is a match surely made in heaven.

I poured two of these six myself – a Brazilian and a Tanzanian – within a few months of each other.

The other four were from cafes – I can’t name dates, but I can list places. And flavours. One came from Coffee Dominion in Townsville, one was from One Drop, one was from Shucked Espresso, and one was from Merriweather – these three cafes are in Brisbane. Two of these were on blends that were carefully orchestrated and calculated to stimulate and excite the senses. I’ve had exceptional coffees from cafes too numerous to mention. But these are the memories that stick. Feasts for the senses.

- The Coffee Dominion coffee reminded me of butterscotch.

- The One Drop coffee was on a day that I was flying up to North Queensland in my first year back in Brisbane, and I still remember the toffee-apple after taste as I drove home.

- The one from Shucked was a Costa Rican that evoked a strong sense of lemon meringue pie.

- The coffee from Merriweather was two Sundays ago – I don’t know quite how to describe the blast of sweet fruity flavours that cut through the milk in my flat white. You know a coffee is good when you text the roaster to thank them.

These moments stand out in what is almost literally an ocean of coffee. Well. About 175,200mL of coffee.

175 litres of exceptional coffee.

Coffee made in the best cafes in Australia. Coffee systematically and methodically produced at home, or at the hands of some of Australia’s best baristas. And despite limiting the search to the cream of the crop the God Shot has appeared for me 0.1% of the time (if my maths is right – it rarely is). Even if I add my next 20 or 30 favourite coffees we’re still at less than 1%.

I’ve got fancy equipment. I’ve tried roasting my own coffee. I’ve tried sourcing coffee from the best roasters wherever I go. I’ve read about coffee. I’ve practiced and honed the craft of espresso extraction. And my success ratio is significantly smaller than the percentage of God Shots to shots.

I drink more coffee at home than out, but God Shots from elsewhere outnumber the coffees I’ve produced three to one.

HOW DO YOU PRODUCE A GOD SHOT?

Mark Prince’s symposium of baristas (surely the official collective noun for a group of baristas?) agree that while the God Shot requires the perfect preparation – the perfect preparation is no guarantee of a God Shot.

The God Shot will not be tamed by human ritual or superstition.

The God Shot is not subject to the whims of the one searching for it, but one must search in the right places.

“Do everything right, and hope for the best.

That’s it. Do your prep the right way – make sure you’re using the best quality specialty coffee beans you can get, fresh roasted and well blended. Make sure your grinder is working in tip top shape and it is a top notch grinder. “Be at one” with your grinder, as in know how your grinder will react to the beans you put in it, know about the tiny things such as humidity, ambient air temperatures, age of the beans and the like, and adjust the grind accordingly.

Make sure your espresso machine is set up right, and running right. Know the proper temperatures and boiler pressures your machine needs to pull off a great shot. Keep your equipment clean.

Prepare your portafilter with all the skill and experience you can muster. Dose the exact proper amount. Level it off, get ready to tamp, and do your tamp. Tamp and spin and wipe. Flush the grouphead for a second or two, even on the commercial machine in a high volume shop. Lock and load, set up the cup and brew.

And hope (or more appropriately pray) for the best.

Do the things right, and you’ll get a great shot of espresso every time. But great doesn’t equal a God Shot. Why? Even the most seasoned, professional and passionate Baristas know they can pull great shots, but also know the God Shot only comes if the stars are aligned, the moons in phase, Jupiter is in Venus, yada yada… oh yeah, and for some who believe in it, God looked down, and decided, yes, this one is worthy, I bless it.”

// Mark Prince, coffeegeek.com

The religious pursuit of the God Shot highlights the problems with all human religiosity – we don’t control God via a series of buttons, variables, and levers, which can be carefully balanced to deliver us a desired outcome. The God Shot mocks our desire to be in control.

THE GOD SHOT AS (UNATTAINABLE) JOY

My experience of the God Shot is fleeting – and I’m not alone. But it’s also what keeps me going back for more, hoping that I’ll taste it again.

This reminds me of CS Lewis’s (and Rammstein’s) concept of sehnsucht.

CS Lewis writes about the fleeting experiences of joy we have now, in this world, and how their fleeting nature reminds us that we are not yet home. We are not where we were created to be – our world is not what it was created to be. Coffee is not yet what it was created to be. And the gap between our experiences now and what we anticipate – the gap that drives our longings – our cravings – and their final satisfaction… that’s this sehnsucht.

“That unnameable something, desire for which pierces us like a rapier at the smell of bonfire, the sound of wild ducks flying overhead, the title of The Well at the World’s End, the opening lines of “Kubla Khan”, the morning cobwebs in late summer, or the noise of falling waves. It appeared to me therefore that if a man diligently followed this desire, pursuing the false objects until their falsity appeared and then resolutely abandoning them, he must come out at last into the clear knowledge that the human soul was made to enjoy some object that is never fully given–nay, cannot even be imagined as given–in our present mode of subjective and spatio-temporal experience.”

// CS Lewis, PILGRIM’S REGRESS

This is the same sense I think I feel when it comes to the fleeting experience of the God Shot, and the desire that sparks… CS Lewis also speaks of joy in similar terms…

“All joy (as distinct from mere pleasure, still more amusement) emphasizes our pilgrim status; always reminds, beckons, awakens desire. Our best havings are wantings.”

// CS Lewis, LETTERS

He speaks of this momentary experience of joy – which, again, describes these six coffees.

“It was a sensation, of course, of desire; but desire for what?…Before I knew what I desired, the desire itself was gone the whole glimpse… withdrawn, the world turned commonplace again, or only stirred by a longing for the longing that had just ceased. In a sense the central story of my life is about nothing else… an unsatisfied desire which is itself more desirable than any other satisfaction…”

// CS Lewis, SURPRISED BY JOY

As an example of joy, provided by something God has created, the God Shot (and the quest for the God shot) reminds us that God is good, and that we are not home. That we are only seeing glimpses of heaven in our coffee cup. It’s a bit like the God Shot – both in its presence and in its absence – helps us see what the writer of Ecclesiastes says in chapter 3.

“He has made everything beautiful in its time. He has also set eternity in the human heart; yet no one can fathom what God has done from beginning to end. I know that there is nothing better for people than to be happy and to do good while they live. That each of them may eat and drink, and find satisfaction in all their toil—this is the gift of God.”

// ECCLESIASTES 3:11-13

THE GOD SHOT AND THE HEART

“For although they knew God, they neither glorified him as God nor gave thanks to him, but their thinking became futile and their foolish hearts were darkened… They exchanged the truth about God for a lie, and worshiped and served created things rather than the Creator”

// ROMANS 1:21, 25

“Stop drinking only water, and use a little wine because of your stomach and your frequent illnesses.”

// 1 TIMOTHY 5:23

Coffee is actually good for your heart (and many other aspects of your health). But the way we consume coffee reveals that our hearts are profoundly diseased in a non-medical sense, and this disease permeates our every action, and our every use of the good things God has made.

Our hearts are diseased in such a way that when they control our hands and mouths we perpetuate this disease – inflicting it on others.

Our use of coffee – when it’s not properly directed to giving glory to the creator for what he has made, joyfully co-creating with his good gifts – falls into two opposite and equally pernicious uses of God’s world. We trash it, or we worship it. While both ends of the coffee spectrum – instant or specialty – can involve trashing or wrongly treasuring creation (rather than the creator), they tend to gravitate towards either pole.

Coffee helps diagnose our diseased hearts. We speak casually of coffee addiction, when what we really mean is dependence. We’ve become slaves to this created thing. The labels we apply to coffee – at either end of the quality spectrum – reveal our idolatry. Instant coffee. Specialty coffee. The narrative we use to surround our consumption of coffee is part of the narrative of our lives – and if it isn’t connected to God, this is a problem.

THE SIN(S) OF INSTANT COFFEE

Instant coffee is symptomatic of the spread of our destructive disease into God’s world – the root cause may well be described as idolatry, but it’s the idolatry of self. Instant coffee. Instant gratification. An instant fix. Caffeine is this tool we’ve harnessed to further our ends, and instant coffee is the most efficient delivery mechanism that maintains some sort of veneer of pleasure (or connection to God’s wondrous coffee bean – I mean, you could take caffeine tablets or inject caffeine – but who’d want to do that?).

But is it instant? Really? We do not question. We don’t need to. Instant coffee is simply fuel, not fun. It’s all science, no art. Pure utility. It is instant. Quick. Cheap. Easy. To focus on the process is to miss the point – or, a lack of focus on the process is precisely the point.

‘Instant’ is a counterfeit claim. It’s not instant (it’s also arguably not coffee). But we want to be ignorant of everything leading up to our fix lest it reveal the deception inherent in the name, and the narrative.

The soluble instant coffee crystal is produced by a convoluted process that, in its lack of care for the world and its people, is both symptom and symbol of our corrupt hearts. It’s a symbol of our quick-paced, fix-driven world of convenient utility and productivity, and a symptom of the corruption we sow wherever our diseased hearts pump sin around our bodies and into our actions.

Our consumption of ‘instant coffee’ involves our consumption of the world around us – consuming both people and planet on the altar of our own convenience.

While much of the world’s coffee – including coffee at the specialty end – is produced in under-developed countries, and many coffee farmers are underpaid (passing that underpayment on to their workers – or slaves) – instant coffee uses the cheapest and nastiest coffee grown in the worst conditions.

The drive to supply the ever-increasing insatiable desire for coffee (largely in the developed west) is leading to deforestation in some of the planet’s most significant rainforests.

The coffee grown for instant coffee is much less likely to be ‘ethical’ on either the environmental, economic, or personal front than anything further along the spectrum towards specialty. This is because the people drinking it care less about quality, and less about process.

Instant coffee is not mankind creatively using God’s good gift to bring life. It’s destructive. This destruction spans the entire process – from planting to packaging, and arguably includes the way the coffee itself is treated – roasted without care, batch produced, dehydrated and crystallised using either extremely hot air or snap freezing. Subjectively speaking it’s hard to see how the generic approach to coffee production – where the only distinction in quality or process appears to be which process is used to crystallise the coffee – can point you to the good and creative creator better than specialty coffee – but if you love the taste of instant, and think you can drink it to the glory of God, then go for it. But remember…

“Most of the ethical problems in today’s coffee industry occur with poor quality Arabica coffee (ie Arabica which is grown at low altitudes, and poorly processed) and most of the world’s Robusta. This low cost coffee predominantly ends up in jars of instant coffee. Many of the large companies that use this coffee don’t purchase based on quality, their most important factor is price — as low as possible.”

// Five Senses, What is Ethical Coffee

Here’s a rule of thumb. If something you enjoy, that you didn’t produce by the sweat of your brow, is really cheap, then someone else has paid the price. It could be this kid.

Image Credit: The Atlantic.

THE SIN(S) OF SPECIALTY COFFEE

“…the human mind is, so to speak, a perpetual forge of idols… The human mind, stuffed as it is with presumptuous rashness, dares to imagine a god suited to its own capacity; as it labours under dullness, nay, is sunk in the grossest ignorance, it substitutes vanity and an empty phantom in the place of God. To these evils another is added. The god whom man has thus conceived inwardly he attempts to embody outwardly. The mind, in this way, conceives the idol, and the hand gives it birth…”

// Calvin, INSTITUTES, I.XI.8

Lest you think I’m only prepared to point the finger at the side of the coffee spectrum I’m biased against – the specialty end of the coffee spectrum is every bit as pernicious. Where instant coffee denies the significance of process, specialty coffee celebrates it – praising the human ingenuity of farmer, roaster, and barista. The idolatry associated with this emphasis on process and control also sees the end user forging their identity on the basis of their consumption decisions.

You are your coffee order. I’ve got no doubt this is true, because it has, at times, been true for me. Here’s a description of the modern obsession with the designer life based on curated choices…

“We declare our individuality via our capacity to consume differently — to mix purchases from Target with those from quirky Etsy shops — and to tweet, use Facebook, or pin in a way that separates us from others . . . Unique taste — and the capacity to avoid the basic — is a privilege. A privilege of location (usually urban), of education (exposure to other cultures and locales), and of parentage (who would introduce and exalt other tastes). To summarize the groundbreaking work of theorist Pierre Bourdieu: We don’t choose our tastes so much as the micro-specifics of our class determine them.”

// Anne Petersen, ‘Basic is just another word for class anxiety,’ buzzfeed.com

If you want to order the ‘single origin honey processed Costa Rica De Licho as a double shot, three quarter latte, with the milk at 62 degrees’ and you know what each of those things contributes to the taste, and you care so much that you won’t accept any less – then you’re probably engaging in what CS Lewis calls the Gluttony of Delicacy.

“She would be astonished—one day, I hope, will be—to learn that her whole life is enslaved to this kind of sensuality, which is quite concealed from her by the fact that the quantities involved are small. But what do quantities matter, provided we can use a human belly and palate to produce querulousness, impatience, uncharitableness and self-concern?”

// CS Lewis, SCREWTAPE LETTERS

Sound familiar. Enslaved to sensuality? The woman described in the Screwtape Letters is one being led away from God by her particular tastes, her desire for her needs to be met in just the right way.

“You will say that these are very small sins, and doubtless, like all young tempters, you are anxious to be able to report spectacular wickedness. But do remember, the only thing that matters is the extent to which you separate the man from the Enemy. It does not matter how small the sins are provided that their cumulative effect is to edge the man away from the Light and out into the Nothing. Murder is no better than cards if cards can do the trick. Indeed the safest road to Hell is the gradual one—the gentle slope, soft underfoot, without sudden turnings, without milestones, without signposts.”

// CS Lewis, SCREWTAPE LETTERS

Specialty Coffee is much more likely to be ethically produced. Partly because specialty coffee producers are generally nice people and want to do the right thing, and partly because partnerships on the ground with coffee growers will produce a guarantee of supply and allows the specialty industry to have some control over growing conditions – ensuring a better quality crop. Here’s the thing – such is the disease of our hearts – that even our most altruistic moments are part of a ‘triple bottom line’ approach to life – there’s a sense that we are ethical in our decision making because it is a way to buy some sort of indulgence to mitigate our consumption of the world around us.

We are often ethical because it makes us feel better. If we this wasn’t the case then the ethics of a particular coffee wouldn’t be a massive marketing tool. We’d care more about whether or not ethical systems like Fairtrade actually work (they don’t really, relationship based coffee purchasing seems to be the most ethical approach).

Or, we’re ethical because we see the good that our conscientious purchasing decisions do for someone else, and feel a sense of pride that our consumption is making a difference, which frees us to consume more, and invites us to continue to find our identity – or our point of difference – in just how special our decisions are. For us, and others.

The way our diseased hearts affect even our good deeds is the result of what Martin Luther called humanity curved in upon itself (or, in Latin, incurvatus in se) – even our good deeds are directed to our own glory, not to God’s. Even our good use of the coffee bean becomes a chance for us to celebrate our own ingenuity.

The pitfalls of ‘specialty’ coffee aren’t just limited to the bench seats of your local small-batch roaster. They’re just as prevalent in the coffee laboratory of the home coffee snob, who seeks to outsnob the other shots, to pour the most consistent god shots, to control every possible variable with increasingly complex (and expensive) equipment allowing minute adjustments to be made to the grind size, the temperature, the pressure, the water purity – every variable can be tweaked in the pursuit of that elusive and fleeting moment of joy. Joy that should be found in the appreciation of the one who made the coffee bean, and gave us taste buds. This joy is counterfeit joy. It is pleasure. And we seek to stimulate the senses as they grow and develop. The bar keeps raising. We’re never satisfied. We invest in bigger. Better. Brighter. We become discontent. Upgraditis is another word for idolatry.

Too often the quest for the God shot – for joy, be it in coffee, or any good thing God has made, becomes the ultimate quest.

THE SIN OF DELIBERATELY BAD COFFEE

You may have heard the line that really good coffee is expensive, so Christians should steer clear of it in order to spend that money on important work. Like telling people about Jesus.

I’ve certainly heard it.

I’ve used it about other stuff.

Like free range eggs and the environment (Thankfully. While the archives of my blog represent my thoughts in the past – our thinking grows as we do…).

But I don’t think you can separate using God’s world rightly and excellently from telling people about Jesus quite so easily.

The God of the Bible is good. He made a good world. A beautiful world. For people to enjoy – to find their joy in him, through the things he made. While there is certainly a place for asceticism – forgoing pleasures – in the face of a gluttonous world, there’s also a place for aesthetics in the good world God has made. For Christians to be modelling the best uses of God’s world in order to point people to the goodness of God. Otherwise, why will people listen to us when we tell them that God is good? God’s goodness isn’t just revealed at the cross of Jesus – though it certainly is revealed there. It’s revealed in the world he made, and his love for it. Jesus didn’t just die to gather a people (though he certainly did that) – his entering the world, his death, and his resurrection are part of the redemption of the world and God’s plans for a new creation – where the joy we experience fleetingly now will become complete.

Our presentation of the good news needs to be embodied, and it needs to mesh with people’s experience of the world. Too much of our evangelism is disconnected from reality – and there’s incredible scope for aesthetic and existential apologetics as well as the philosophical, or historical stuff we normally engage in, so long as we navigate away from idolatry.

Personally, I think this rules out instant coffee. But you might love the flavour, and find other people who do to… and you might be able to overcome the other issues – like the ethical issues – associated with instant. We’ll deal with this a bit more below – where I’ll again, make my case against Instant Coffee.

DIVINE ‘HEART SURGERY’ AND THE RIGHT USE OF COFFEE

“The LORD saw how great the wickedness of the human race had become on the earth, and that every inclination of the thoughts of the human heart was only evil all the time.”

// GENESIS 6:5

“He has made everything beautiful in its time. He has also set eternity in the human heart; yet no one can fathom what God has done from beginning to end.”

// ECCLESIASTES 3:11

So the God Shot points us to the idea that we were created for something better, while our attempts to capture and reproduce it show that we are broken. Our hearts are simultaneously wired to point us to eternity, and diseased in such a way as to sow death at every turn and in our every action (the very opposite of eternity).

Here’s a cool quote from author William Faulkner when he won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1949… this is, in part, why I think an aesthetic/existential approach to sharing the Gospel is worth pursuing.

“Our tragedy today is a general and universal physical fear so long sustained by now that we can even bear it. There are no longer problems of the spirit. There is only the question: When will I be blown up? Because of this, the young man or woman writing today has forgotten the problems of the human heart in conflict with itself which alone can make good writing because only that is worth writing about, worth the agony and the sweat.”

// William Faulkner, NOBEL LITERATURE PRIZE SPEECH, 1949

His whole speech is worth reading – especially if you work as though the poetry he wants people to be writing is an analogy for the God Shot.

The tension in the human heart is not solved by itself – or, as Faulkner suggests – pointing to some higher version of itself. It needs recreation, intervention, a redefinition of what it means for it to beat for its maker again. It needs surgery.

This surgery happens when God makes an incision into time and space, decisively entering to declare both the true trajectory for history, and the true pattern for the human. So, when Paul describes Jesus become a man, within creation, to Timothy, he says:

“Beyond all question, the mystery from which true godliness springs is great:

He appeared in the flesh,

was vindicated by the Spirit,

was seen by angels,

was preached among the nations,

was believed on in the world,

was taken up in glory.”

// 1 TIMOTHY 3:16

This is God performing cosmic heart surgery. This is God pouring himself out on the world. The perfect pour. A multi-sensory experience that redefines every other experience of the senses. It’s only when our hearts are radically realigned with their creator that we can start to appreciate the good things he made the way they were intended to be enjoyed – as good gifts from a good God.

PUTTING COFFEE IN ITS PLACE

Here’s where Paul goes next when he’s talking to Timothy – this little description of Jesus’ entry into time and space – in the flesh – is how Paul is addressing a bunch of wrong thinking about what to do with delicious and nutritious gifts from God (and, indeed, what to do with everything God made).

“They forbid people to marry and order them to abstain from certain foods, which God created to be received with thanksgiving by those who believe and who know the truth. For everything God created is good, and nothing is to be rejected if it is received with thanksgiving, because it is consecrated by the word of God and prayer.”

// 1 TIMOTHY 4:3-5

It’s worth breaking this down – Paul tells Timothy that some hypocritical liars who have abandoned the faith will come telling people not to enjoy God’s good gifts that were there from creation. Marriage. Good food. But these things were made by God “to be received with thanksgiving by those who believe and who know the truth” – and in the context this “knowing the truth” must surely be linked to “the mystery from which true godliness springs” – knowing Jesus. This puts the physical world into perspective. It has value (like physical training), and it frames our labour and our strivings – there are echoes of Ecclesiastes 3 to be found here, because this is where meaning is to be found.

“For physical training is of some value, but godliness has value for all things, holding promise for both the present life and the life to come. This is a trustworthy saying that deserves full acceptance. That is why we labour and strive, because we have put our hope in the living God, who is the Savior of all people, and especially of those who believe.”

// 1 TIMOTHY 4:8-10

The right response to God’s good gifts is not to reject them but to receive them. With thanksgiving. The right response to coffee is not to baptize it – like Pope Clement VIII but to accept it as already good, in line with God’s good intentions for his creation.

When coffee was first introduced to the western world – from Islamic Africa – it was suspiciously treated as the ‘Devil’s Cup’ – before condemning it, Pope Clement VIII asked to try some and apparently said:

“This devil’s drink is delicious. We should cheat the devil by baptising it…”

Coffee is good. It is made by God. It is made by God to be enjoyed so that we are thankful to God – not trashing it, or treasuring it (as God) – but treasuring God through it. In the next couple of chapters Paul says a few other things about how we’re to approach good stuff God has made.

“Stop drinking only water, and use a little wine because of your stomach and your frequent illnesses.”

// 1 TIMOTHY 5:23

“But godliness with contentment is great gain. For we brought nothing into the world, and we can take nothing out of it. But if we have food and clothing, we will be content with that.”

// 1 TIMOTHY 6:6-8

And here is the clincher.

“Command those who are rich in this present world not to be arrogant nor to put their hope in wealth, which is so uncertain, but to put their hope in God, who richly provides us with everything for our enjoyment. Command them to do good, to be rich in good deeds, and to be generous and willing to share. In this way they will lay up treasure for themselves as a firm foundation for the coming age, so that they may take hold of the life that is truly life.”

// 1 TIMOTHY 6:17-19

God provides us with good gifts for us to enjoy them. We are rich – especially when it comes to the coffee world – our consumption of coffee is a chance for us to enjoy God’s creation, do good deeds, and be generous to others, with our senses fixed on the true life to come.

USING COFFEE TO TELL GOD’S STORY, NOT OUR OWN

“I am not, however, so superstitious as to think that all visible representations of every kind are unlawful. But as sculpture and painting are gifts of God, what I insist for is, that both shall be used purely and lawfully,—that gifts which the Lord has bestowed upon us, for his glory and our good, shall not be preposterously abused, nay, shall not be perverted to our destruction.”

// John Calvin, INSTITUTES I.XI. 12

So. To wrap up. And here’s where I get a little more speculative – feel free to disagree with me…

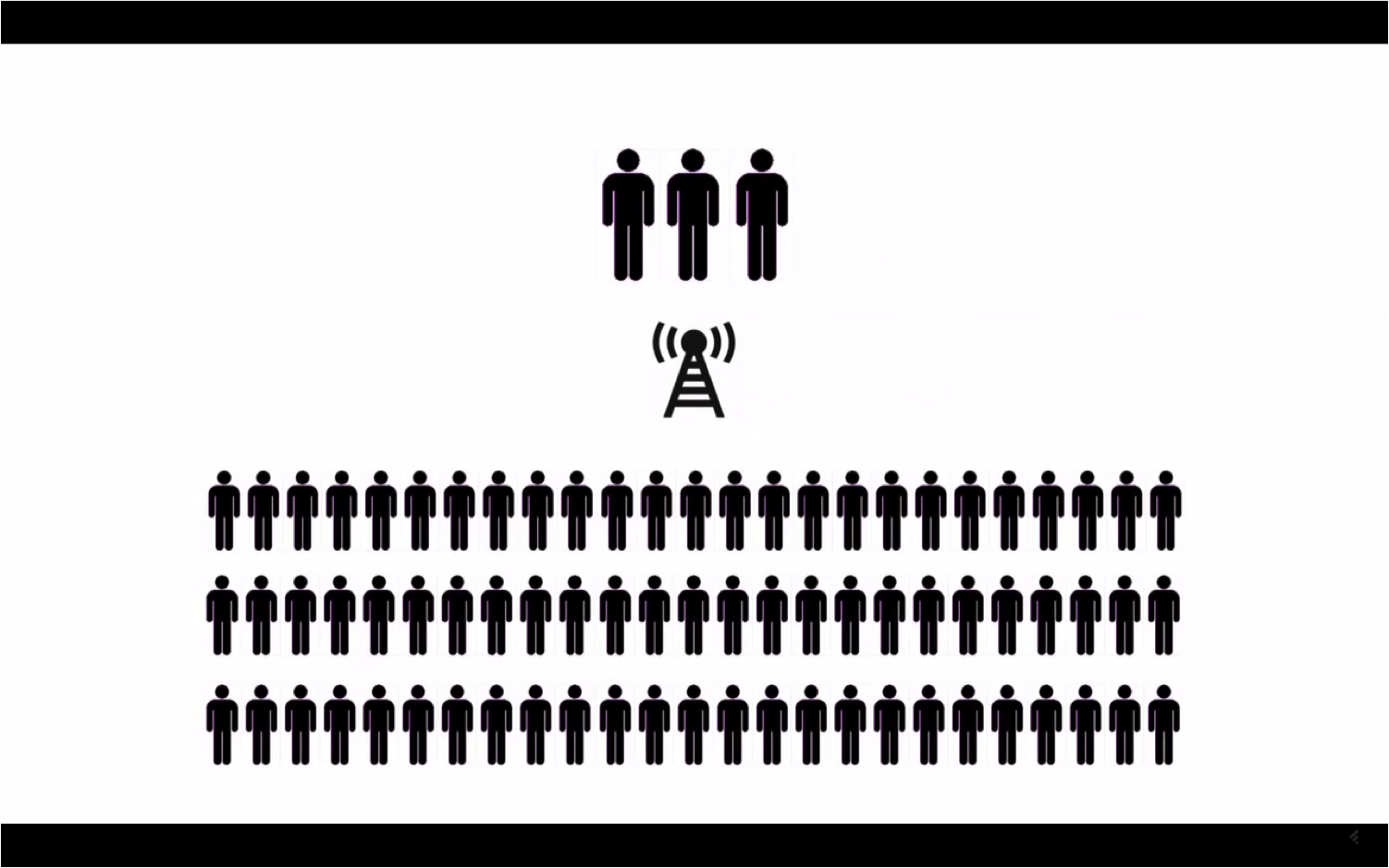

Lets assume for a moment that when Romans talks about the function of what God makes it’s not our job to sit passively by why the heavens point people to God.

This seems pretty clear. A long held understanding of ‘natural theology’ -which is basically the understanding that we can know of God from nature – is that nature might point us to a God (enough to earn us judgment), but it won’t point us to God as he reveals himself in his word, and in Christ. So, people then think we should focus on sharing this special revelation from God – teaching God’s word and preaching about Jesus… This might be where the “don’t spend money on coffee when you can spend it on Jesus” idea comes from. This involves ignoring one stream of God’s revelation to us (about his character and qualities) in order to promote another. Why not do both?

“For since the creation of the world God’s invisible qualities—his eternal power and divine nature—have been clearly seen, being understood from what has been made, so that people are without excuse.”

// ROMANS 1

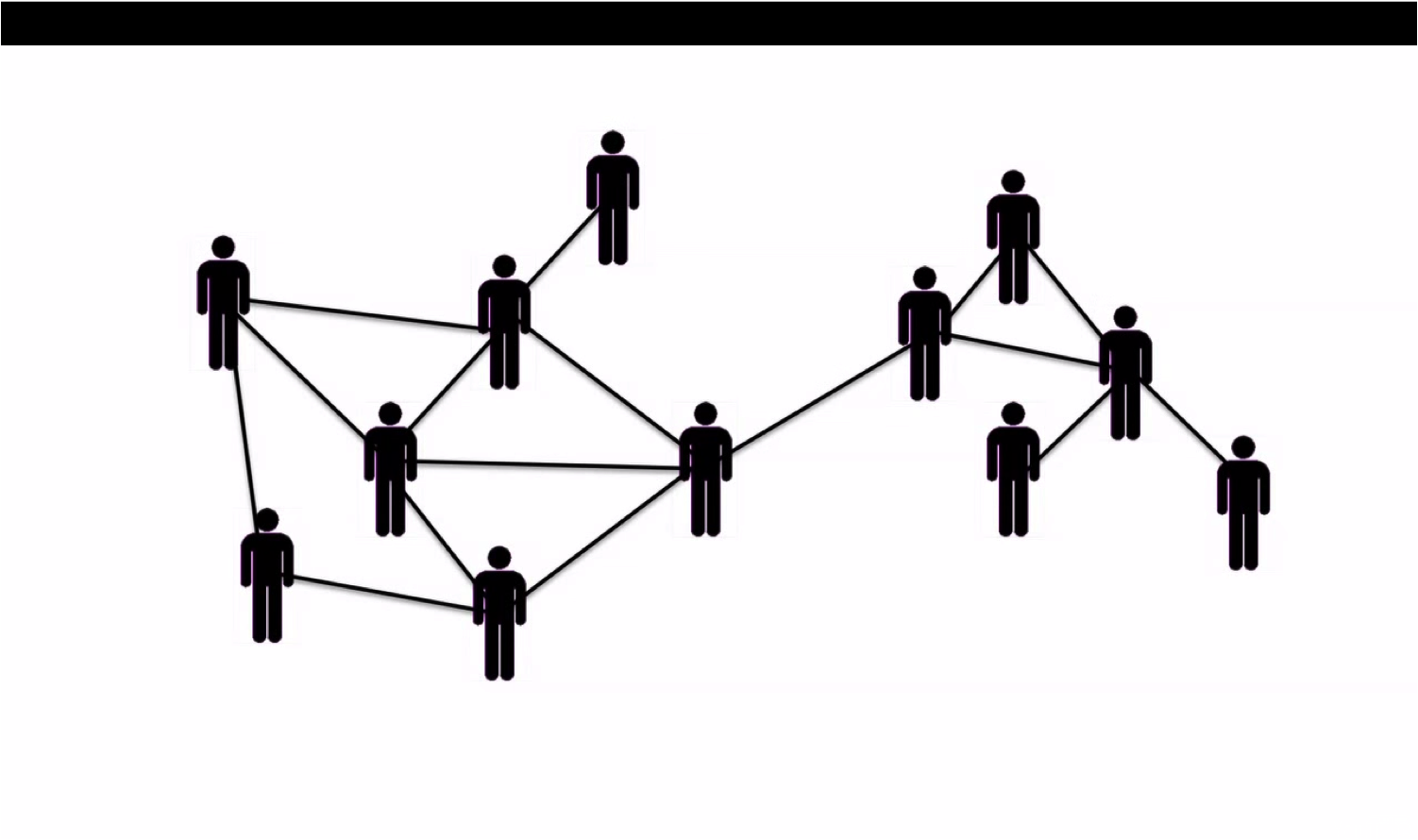

So. If what a few people call ‘God’s second book’ – what has been made – is meant to point us to God why don’t we think his people have a responsibility to interpret ‘what has been made’ and use it rightly to point people to the maker?

And. Is there any evidence to suggest this is how we should think of the world God has made?

I think so. The Calvin quote shows this sort of idea isn’t novel. But here’s a cool thing – when God creates his people and puts them in the garden, we’re told about the other stuff God makes.

“The name of the first is the Pishon; it winds through the entire land of Havilah, where there is gold. (The gold of that land is good; aromatic resin and onyx are also there.)”

// GENESIS 2:11-12

This is such a bizarre thing to mention. God made lots of other stuff. But we get this mention of some (presumably) really good things he made. Gold pops up all over the place – including when Israel is escaping Egypt.

“The Israelites did as Moses instructed and asked the Egyptians for articles of silver and gold and for clothing. The Lord had made the Egyptians favorably disposed toward the people, and they gave them what they asked for; so they plundered the Egyptians.”

// EXODUS 12:35-36

We’ve covered our tendency towards idolatry already. The tendency to turn God’s good gifts into God, treasuring them too much. Look what happens when Israel is waiting around at the foot of the mountain while Moses speaks with God.

“When the people saw that Moses was so long in coming down from the mountain, they gathered around Aaron and said, “Come, make us gods who will go before us. As for this fellow Moses who brought us up out of Egypt, we don’t know what has happened to him.”

Aaron answered them, “Take off the gold earrings that your wives, your sons and your daughters are wearing, and bring them to me.” So all the people took off their earrings and brought them to Aaron. He took what they handed him and made it into an idol cast in the shape of a calf, fashioning it with a tool. Then they said, “These are your gods, Israel, who brought you up out of Egypt.”

// EXODUS 32:1-4

Gold. The good stuff God made, that was there at Adam’s disposal, presumably to help remind humanity that God made a good world (the constant refrain in Genesis 1). It has become an idol. It is not revealing God. His second book is not being properly understood – or taught by his people. Here’s another reference to Gold – being rightly used – from the Old Testament. This is Gold being used to tell God’s story – to bring ‘general’ and ‘special’ revelation, or God’s two books, together. Note that Moses is being given the design for this priestly garb at the same time that Aaron is turning the gold into an idol, and that it specifically mentions onyx (there in Genesis 2), and that it makes mention of the artistry of the human craftsman…

“Make the ephod of gold, and of blue, purple and scarlet yarn, and of finely twisted linen—the work of skilled hands. It is to have two shoulder pieces attached to two of its corners, so it can be fastened. Its skillfully woven waistband is to be like it—of one piece with the ephod and made with gold, and with blue, purple and scarlet yarn, and with finely twisted linen, and finally, that the design, and artistry, has a purpose.

“Take two onyx stones and engrave on them the names of the sons of Israel in the order of their birth—six names on one stone and the remaining six on the other. Engrave the names of the sons of Israel on the two stones the way a gem cutter engraves a seal. Then mount the stones in gold filigree settings and fasten them on the shoulder pieces of the ephod as memorial stones for the sons of Israel. Aaron is to bear the names on his shoulders as a memorial before the LORD”

// EXODUS 28:6-12

Coffee is gold (it’s a metaphor – like in those banking ads).

The pursuit of the ‘God Shot’ so long as it is rightly framed by the pursuit of the God who made the coffee, is a way to both enjoy God’s creation with thankfulness, and point others to it.

As you pursue perfection (while knowing it is unattainable this side of God’s new creation), applying ingenuity, science, and art, to achieve the very best cup of coffee possible – so long as you are not turning coffee into an idol – you have a chance to tell God’s story, and ours.

If God brews coffee in heaven (it may well be tea) – I can’t imagine him serving up anything that tastes like International Roast. I don’t think you can truly reveal God’s character from a cup of instant coffee – not when you see the contempt with which it treats his creation, and not when you make the comparison to the significantly richer double ristretto that tastes as good as ground coffee smells.

This is where God’s good creation meets art, meets science, to the glory of a transcendent creative and good God.

God’s story is the gospel – his story of redemption of our broken hearts, and their realignment to him through Jesus. Our use of the world he made should mirror that realignment, and tell that story. This has to change our consumption habits for the benefit of our neighbours – global and local.

Good coffee is proof that God is good.