This was a sermon preached at City South Presbyterian in 2024. You can listen to the podcast here, or watch it on video. Some of the block quotes were on screen and summarised but have been included in full.

Let’s talk about Paris. The city of love and liberty — from kings and from gods… any gods.

Let’s talk about the 2024 Olympics — a public, global event where all the nations of earth come together in a festival, celebrating the human body and the human spirit. An event tracing its heritage back to Greek paganism, that now includes people from every tribe and tongue and nation and religion.

And — let’s talk about the opening ceremony.

Did you see it?

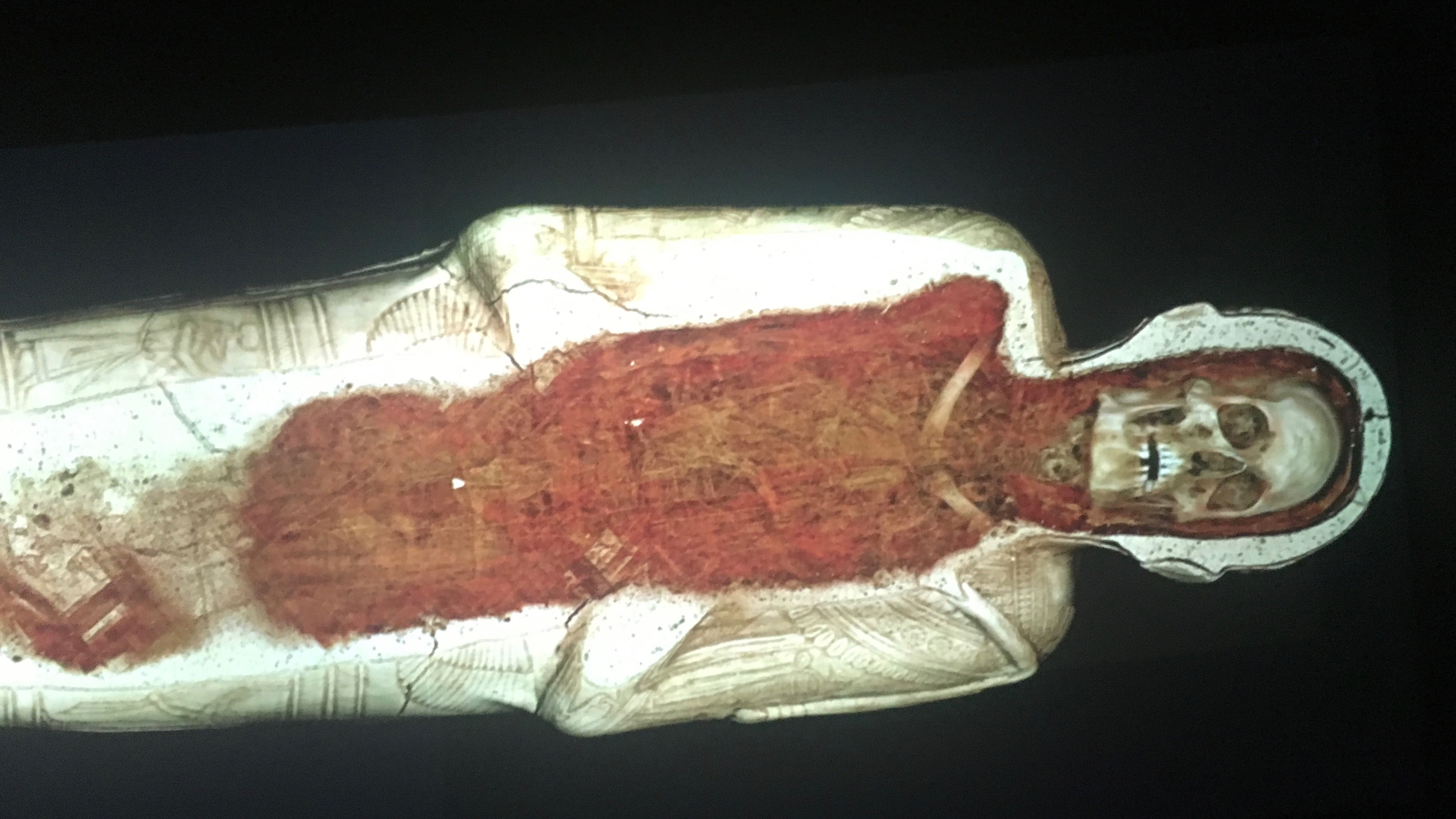

In a performance that ran through France’s secular history — its revolution and liberation so it’s now a society that celebrates unrestricted love and beauty — there was a fashion show that became a bacchanalian feast, and there was a moment where Jolly created a scene that looked like Da Vinci’s painting of the Last Supper.

That’s an important distinction — right — that he copied a painting of the Last Supper, not the Supper itself. We Presbyterians have a tradition of thinking any representation of Jesus in a picture runs the risk of violating the second of the Ten Commandments — whether it’s Da Vinci’s white Jesus, or Jolly recreating that scene with Jewish lesbian, Barbara Butch.

Jolly re-presented this painting using humans; re-framing a famous artwork consistent with his own religious convictions. Describing his intention he said:

“We wanted to talk about diversity. Diversity means being together. We wanted to include everyone, as simple as that.”

We’ll come back to this.

Because as the camera zoomed out in the opening ceremony it was clear this wasn’t just the Last Supper — Da Vinci didn’t paint a smurf on a platter.

The performance was (apparently) a homage to a painting, The Feast of the Gods, by Jan van Bijlert from the 1600s, which you can find hanging in a French gallery.

People who made this connection suggested Christians were silly to be outraged; we should calm down; it’s not even a painting of Jesus — only — the French museum has a guide to its artworks where — in a bad French-to-English Google translation — we’re told the Reformation meant less demand for paintings in “temples,” which I assume is a translation of “churches”:

“In the context of the Reformation, in which the commission for temples had disappeared, the artist found a stratagem to paint a Christlike Last Supper under the cover of a mythological subject…”

With mythological, pagan features… the Greek gods feasting on Mount Olympus. Apollo in the place of Jesus. All the gods are included, as Jesus is replaced.

And, just for fun — there’s another painting hanging in a gallery in Paris — a Last Supper scene on the River Seine — its title is a pun; I won’t mangle the French but “Last Supper,” “the scene,” and “the Seine” all sound the same.

When Paul visited Athens he was introducing a new God to a pagan landscape. Where we sit, any religious revolution — any paganism — has to account for Jesus and his impact on the west. While most of the ancient Athenians laughed at the idea of a resurrected God, who had been mocked and ridiculed — powerless — on a cross, modern paganism laughs at a God they have found repressive, exclusive, and powerful.

Anyway. How did this image — this event — this mockery and idolatry make you feel?

Whether you interpreted it as a direct insult to an image of Jesus, or just the image of a feast of pagan gods supplanting Christianity’s claims of exclusivity in the west, in the name of inclusivity of people often excluded from the table by Christians… however you saw it — what was your response?

Disorientation?

Offence?

Distress?

And what’s your response to the response — both from other Christians, or the apology from the Olympic committee — or to the death threats received by the person at the centre of the image, or by the artist — or the Vatican issuing a statement condemning the display?

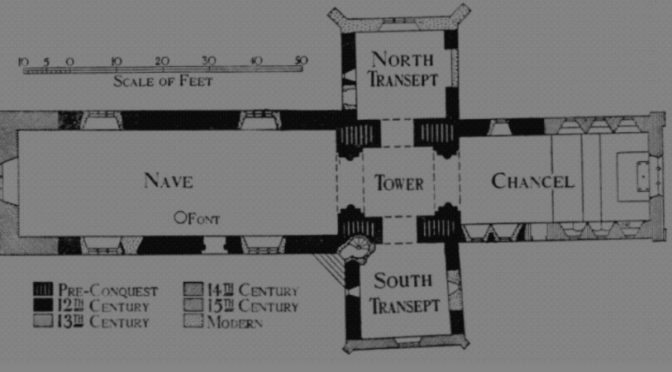

How you think we should respond or react to this is kind of a picture of where we are up to in our series today about inhabiting the world. We’ve looked at building our own lives, at being part of a household or family, at creating habitats that shape us in our homes or church spaces. This week we’re thinking about how we live in public; in cities — or a world — designed with its own conforming pattern; its own architecture or habitats that shape hearts and minds.

How we react to this moment around a global festival, this overt display of religious worship, this appeal to form our minds is a bit of a test case; a way to explore how we imagine life inhabiting spaces like Athens, or Paris, or Brisbane, as people who have inhabited and been formed by the living God — as his temples.

We started our series in Athens, where we saw Paul’s reaction to the pagan art and performances of that city — its idols, and altars, and temples — he was greatly distressed (Acts 17:16). It’s literally the word provoked.

I think some of us are hard to offend and might minimise the distress others feel in response to blasphemous dismissals of the God we worship; the desire to see his name hallowed. We might miss that idolatry is an affront to God, and not be provoked by this enough — whether the performance was directly the Lord’s Supper, or just a pagan feast replacing it — but I reckon some of Paul’s distress is not just about love for God, but love for humans — and his understanding of what idolatry does to humans; how it excludes us from life with God; life at his table.

Paul’s distress doesn’t just lead to a classic Old Testament response to idols — he doesn’t tear them down or smash them with a hammer or “devote them to destruction” like Deuteronomy says:

“This is what you are to do to them: Break down their altars, smash their sacred stones, cut down their Asherah poles and burn their idols in the fire.” — Deuteronomy 7:5

He preaches to them. He invites them to the table, to meet the living God (Acts 17:18).

He uses their human impulse to worship; their idols and altars (Acts 17:22-23) — their artists, poets, and philosophers to point them to their Creator (Acts 17:28) — who made them to inhabit time and space (Acts 17:26)… and to seek and find him (Acts 17:27). He uses all this architecture — including art and images — and their desires — to aid this search; pointing them to the Creator they are ignoring in their pagan worship.

He doesn’t come with a hammer, but he calls them ignorant — and tries to inform them so they might be transformed. While God overlooked this offensive paganism in these nations before Jesus, now he commands all people to repent (Acts 17:30); to leave the gods of Mount Olympus and their feasts and festivals to find transforming life at God’s table, with him. God, our creator, has us inhabiting space and time so that we might find him, and the way to find him is through Jesus, in his kingdom.

This speech in Athens is part of Luke’s two-part volume about who Jesus is and what his kingdom looks like. When our church worked through Luke’s Gospel earlier this year, we saw how this kingdom is revealed at the table:

“When the hour came, Jesus and his apostles reclined at the table… he took bread, gave thanks and broke it, and gave it to them, saying, ‘This is my body given for you; do this in remembrance of me.’” — Luke 22:14, 19

Whatever that meal symbolises, it is a picture of life feasting with God, and how God invites us to this feast through Jesus. Our desire to be included in human community might well be part of how God has wired us to look for connection and belonging and inclusion — a desire that is best fulfilled at his table, rather than filled with pagan feasts.

And we’ve seen how the Christian habitat for being formed as God’s people is a household — homes, spaces where people meet together and break bread, remembering Jesus’ body and his blood given for us so that we might become children in God’s family; so we might be transformed as we turn away from destructive idols, and patterns of life, and inhabit the city differently.

But what should this look like? This transformation? Life in this kingdom? Life at this table — and why choose it rather than the feast of the gods around us?

If you think way back to the start of the year to our second talk in the Luke series (podcast here), we saw how in Luke Jesus proclaimed the good news — the Gospel — as the beginning of a party with God, the year of Jubilee (Luke 4:18-21). He came to fulfil this.

Some part of inhabiting the world as those feasting at God’s table involves this preaching — a proclamation that comes as an invitation to feast at God’s table, and away from other tables, altars, and gods.

We get a picture of this transformation from the Old Testament passages Jesus says he fulfils. His good news announcement of Jubilee comes from Isaiah 61 — which is good news for the poor and the oppressed, for captives who are in the dark (Isaiah 61:1). Now — we either tend to read this and see a picture of justice being meted out for any oppressed people, and see God’s heart to include excluded and oppressed people — or we tend to spiritualise this idea of freedom and rescue and make it just about sin and forgiveness. And God certainly liberates us from sin and death and the rule of other powers and principalities. But Isaiah is written to the nation of Israel, and this is — as much as anything — a promise that exile from God will end; that being excluded from his presence is not forever; that God will regather a people for himself.

And those of us reading after Jesus who are Gentiles — most of us — this regathering comes with bonus inclusion: the end of an exile from God for all nations, nations who had worshipped other gods, with pagan feasts like the one on Mount Olympus. Pursuing liberty — freedom from God, freedom to rule our own lives and pursue our own feasts.

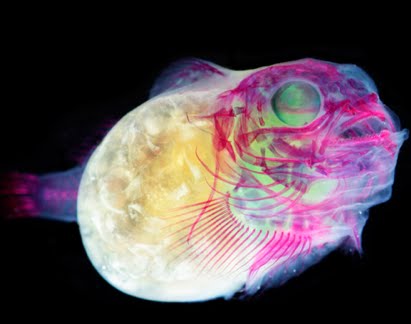

Isaiah suggests this idolatry is destructive and dehumanising — we become what we worship:

“All who make idols are nothing, and the things they treasure are worthless. Those who would speak up for them are blind; they are ignorant, to their own shame.” — Isaiah 44:9

And we are left “feeding on ashes” (Isaiah 44:20). The worst thing is to be formed in the image of these false gods, and to find ourselves as enemies of the God of all nations.

Anyway — Jubilee is not just about liberation and inclusion and diversity. It is about invitation and transformation. Through it, God will take those — first of all — those of his people on Zion — and replace their ashes, the way they had been marked by mourning, with a crown of beauty. Bringing the oil of joy instead of mourning. This is beautiful imagery, isn’t it? Restoration. God will make these people righteous; like trees planted to display his splendour (Isaiah 61:3). These people will be rebuilders of cities — specifically in this case it is about Jerusalem — they will create shared architecture that points to life with God (Isaiah 61:4). They will be priests of the Lord, benefiting from the produce of fields and vineyards, receiving abundance — a double portion, an inheritance. Joy-filled (Isaiah 61:6-7).

God will make a covenant with this people and reward them. Their descendants will be known among all the people of the world as his blessed people (Isaiah 61:8-9); clothed in salvation and righteousness; a fruitful, garden-like people who will multiply praise as God makes them grow in righteousness (Isaiah 61:10-11). This is what Jesus says he fulfils. This is the sort of people we are invited to be as we become part of his household. This picture of life as God’s people — who dwell at his table and model fruitful life in the world.

How should this idea of being fruitful, righteous, rebuilders of cities work when we live in cities more like Athens than the new Jerusalem?

Another image that might help comes from another prophet, Jeremiah, who talks about God’s people preparing themselves for the promised end of exile while still living in Babylon. God promises them they will return to life with him, and to prepare by building houses and planting gardens — creating homes that operate as habitats where they are formed as God’s people; gardens that echo Eden and the temple they lost (Jeremiah 29:5); being fruitful and multiplying (Jeremiah 29:6); seeking the prosperity of their neighbours because their prosperity will be found as the city prospers (Jeremiah 29:7). God promises he will end their exile — bring them home — but the pattern of life in a hostile city is to build and plant, to generate life, to bless their neighbours, anticipating restoration to life with God — to practice the sort of things Isaiah pictures as restoration.

And there is something very Genesis-y about both these pictures — isn’t there — some explicit language that connects to the mission God gives humans in the beginning. As he blesses them and calls them to be fruitful and multiply (Genesis 1:28); to fill the earth and rule over it as his representatives. And then as he commissions his gardening human to cultivate and keep the garden — his dwelling place — where he gives a feast (Genesis 2:15-16).

So this is who we are to be. God made us to inhabit space and time, and he has called us into life with him. Jubilee life at his table. Life in his kingdom. Calling us to cultivate space — planting and building — that reflects his rule, while inviting others to the party; to be transformed as they find the God who is seeking them through his resurrecting king.

But what does this look like? How do we live like this when there are so many other feasts, other gods clamouring for our worship, forming our minds? Provoking us? We are invited to be cultivators, builders, planters — to live constructively, not to seek the destruction of these idols and their tables or altars.

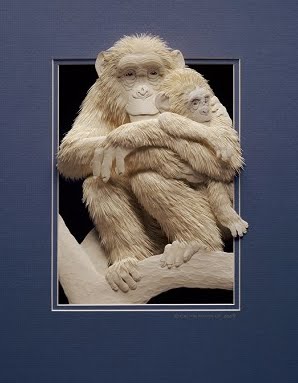

There’s this Japanese-American artist-slash-theologian, Makoto Fujimura. He makes art drawing on his Japanese heritage and his Christian faith, and writes books about how Christians might think about participating in our culture — our Babylons — while anticipating the heavenly city.

Where some folks suggest our job is to fight a culture war, he calls us to culture care, and to an approach that summarises all this Old Testament stuff — to a life of generativity. It’s a good word. He describes it as bringing flowers into a culture bereft of beauty:

“Culture Care is a generative approach to culture that brings bouquets of flowers into a culture bereft of beauty.”

— Makoto Fujimura

Being fruitful and multiplying; generating life.

“God creates and calls his creatures to fruitfulness… We call something ‘generative’ if it is fruitful.”

— Fujimura

He applies this idea to his art — and to critiquing other sorts of art or creativity. And it is a useful idea when we are confronted with art — or life — that feels degenerate: paintings, performances, pagan feasts, idol statues, or modern altars and temples that turn our hearts and habits away from God.

“We can also approach generativity by looking at its shadow, ‘degenerate’ — the loss of good or desirable qualities.”

— Fujimura

This allows us to respond to something degenerate or degrading with imagination; trying to introduce beauty to the ashes. Gardens to Babylon. Where, like Paul in Athens, we focus on being fruitful and multiplying; pursuing abundance; being constructive not destructive — inviting others to encounter this life.

“What is generative is the opposite of degrading or limiting. It is constructive, expansive, affirming, growing beyond a mindset of scarcity.”

— Fujimura

“Generative thinking is fuelled by generosity” that responds to God’s generosity; hospitality that responds to God’s hospitality — reminding us not to commodify or objectify life; to dehumanise other humans, or treat God as an object in our own plans to consume.

He says: “An encounter with generosity can remind us that life always overflows our attempts to reduce it to a commodity or a transaction.”

I love this stuff.

So often the “culture war” dehumanises the other — in the Paris situation this looks like not seeing the humanity of those at the table; and Thomas Jolly or Barbara Butch getting death threats. Generativity means building movements or creating things that seek to make our cities — our culture — more humane and welcoming, and inspire us to be truly human.

“Thinking and living that is truly generative makes possible works and movements that make our culture more humane and welcoming and that inspire us to be more fully human.”

— Fujimura

So. We might see the Olympic opening ceremony — the Olympics themselves, and the controversial “feast” in particular — as degenerate. Degenerating. Like the idols and altars and feasts of Athens; designed to dehumanise. We might — like Paul — be distressed.

But let’s examine not just our distress — but our response. It would be a problem if our distress did not move us towards where it moves Paul: towards inviting people to encounter God as God actually is; to find life in a feast with him. But instead to our own sort of degenerative behaviour where we dehumanise the other, the opponent — where we pick up our sledgehammers and attack the idols with our own angry art.

It would be a problem if, when we saw a table full of people typically excluded from church community and life with God — dressed in drag, or gender non-conforming folks, or queer people like the lesbian DJ Barbara Butch in her crown — we joined the crowd of people yelling hate or sending death threats.

To respond with outrage at the idea that these folks might be included would be to perpetuate their exclusion, and probably to join in seeing them as less than human. And our distress or outrage might be around the idea of who is at that table and what they represent, rather than the portrayal of Jesus.

Reframing Jesus as part of another pagan festival — replacing him with Apollo, and serving up Dionysus — is dumb, insulting, and blasphemous. It is degenerate, as was plenty of the sexual stuff, the celebration of promiscuity around that particular image. It is dehumanising, and like any idolatry it offers a dead end.

The modern idol of inclusion and diversity — without Jesus and the transformation he offers everyone through resurrection and re-creation and life at God’s table as his worshipping image bearers — that’s also a dead end. But it is a longing tied in with our search for meaning, for God, for love and connection and inclusion — the same impulse that led artists and architects to build idols and altars in Athens.

There’s also an interesting sub-thread here with the anger about the inclusion of the “other” in the culture war here — queer folks — at the table. The comparison here is not exact; but where our intuition is to see anything not binary as an affront to God’s design of image bearers as male and female, we have to grapple with one of the primary pictures Isaiah gives us for exile and restoration, and the way he challenges our categories — in a thread explicitly picked up by Jesus.

In Isaiah 39, Isaiah tells the king of Israel that exile is coming; Babylon will cart off his household, and Israel’s images of God — humans — in this case, sons of the royal house will be turned into eunuchs (Isaiah 39:6-7).

For Israel, a man whose sexual organs were mutilated would be excluded from life in God’s house under the law:

“No one who has been emasculated by crushing or cutting may enter the assembly of the Lord.”

— Deuteronomy 23:1

This was common practice in Babylon in a way that reflected their creation story — where the god Marduk creates through violence and dismembering other beings. In Babylon’s religion, only the king was the image of God, of Marduk. Babylon’s kings would routinely gather up the most beautiful sons of conquered nations, and make them into eunuchs to serve the royal household (Isaiah 39:7).

This probably happened to Daniel and his friends, who were literally given to the “chief of his court officials,” which is “chief of the eunuchs” in Babylon (Daniel 1:3-4). Someone made a eunuch before puberty would develop different feminine bodily characteristics. They would not fit a typical gender binary. An Israelite would see this as an affront to God’s design, his law, and an expression of idolatrous worship and power. Such a person would be excluded from the table.

But as Isaiah pictures the return from exile God promises, he pictures eunuchs — the excluded, these humans whose bodies were marked by the idolatrous empire that included them at the royal table, in the king’s family, who do not conform to a rigid gender binary image. They are being included in the temple, God’s house, as a prophetic picture of God’s rebuilding and recreating and liberating work, of Jubilee (Isaiah 56:4-5).

Some religious folks in Isaiah’s day, familiar with the law, may have found this image incredibly provocative and distressing — or they may have been moved by compassion and by excitement to be part of something God was going to do, rebuilding a people.

Jesus continues this inclusivity when he talks about eunuchs as a picture of faithfulness in Matthew’s Gospel (Matthew 19:12). He describes those who are born this way, those made this way by others, and those who choose to live this way for the sake of the kingdom of heaven, as he speaks of those who will choose God’s kingdom over sexual expression that rejects God’s design.

It is striking, too, that the first Gentile we meet included in God’s kingdom in the book of Acts is the Ethiopian eunuch (Acts 8:27)… who is reading Isaiah (Acts 8:32).

Now — this is a broad category and it does not only or exclusively map on to the sorts of people at the table in the opening ceremony image. There are complex dynamics around individual circumstances and biology and sin working out for any person who comes to God’s table seeking inclusion and life with him.

Practicing generativity and generosity will mean looking to see the humanity of the other we might dehumanise, as we build communities with a desire to see all people come to the table with Jesus to be transformed by him as their exile ends and Jubilee begins.

Our reaction to a picture of queer people at the Lord’s Supper, our outrage, risks closing the door to this sort of inclusion; to creating a prophetic community where those harmed by Babylon, or Athens, or Paris, and its worship, find adoption and life in God’s family, at his table. Where we see those in this picture as less than human, or do not desire their presence at God’s table, or close the door, we are missing the pattern of life we are invited into.

A culture war posture of outrage — our response when we feel attacked — might fail to recognise the deep desire folks have for inclusion; to feast at the table of God. To see how when this desire misfires in degraded, degenerative, pagan worship that dehumanises, there is an opportunity to proclaim the one who is at the table offering his body to give life.

What if — though we are provoked, distressed — by pagan parties that mock Jesus — we reacted with a generous invitation, like Jesus does from the cross. Where he says “Father forgive them,” or invites the rebel next to him to join him in the garden.

What if, when we see a picture like this, we do not see an awful attack on Christianity, but — in the artist’s words — a search for inclusivity that, without Jesus and the transformation he offers, is just a dead end.

So we do not pick up the sledgehammer or keyboard in a culture war, but set the table with culture care.

And look — you might say “but this is not what the artist meant, it was deliberately offensive and you are letting them off the hook”… But I am pretty sure the people who built the altar to the unknown God in Athens did not mean for Paul to make it about Israel’s God either.

What if instead of seeing these folks taking the seats of Jesus and his disciples, we saw them at the other side of the table; across from Jesus.

What if we imagine Jesus in this picture offering his body and his blood — his loving hospitality and invitation to these folks just as he did for us? Offering inclusion and transformation to those prepared to repent and be transformed.

What if this was our posture in real life too — not just our reaction to the opening ceremony? To build and plant homes and spaces in our city — amongst the idol tables — that offer this life to others.

What if our building and planting — our generativity — were generated by our own weekly re-enactment of the Lord’s Supper at this table; a picture performed for us, and the world, as we remember and proclaim the good news that Jesus has given his body and blood to include us, to transform us, as we bring our lives, our crowns, and our sin to the table and repent. Laying those things down and taking up the life of Jesus so we might carry it into the world with us.