This is part 4 in a 5 part series on what social media does to our brains. It uses Facebook as a case study – but it’s not just about Facebook. In fact, it’s just as likely to apply to people who use smartphones… A study from the University of Winnipeg found:

“The values and traits most closely associated with texting frequency are surprisingly consistent with Carr’s conjecture that new information and social media technologies may be displacing and discouraging reflective thought.”

Part 1 established that there is good reason to believe that the communication mediums we use change the way we communicate and relate (media ecology), and thus change the way we think, in turn rewiring our brains (neuroscience and neuroplasticity), and that there is good evidence that this is consistent with a Christian view of the world. Part 2 considered how we might approach this emerging consensus about the impact of social media from the perspectives of media ecology and neuroscience. Part 3 considered how this fits in with a Christian view of the world – in these posts the conclusion was the same – mediums aren’t neutral, they contain powerful “myths” that conform their users to a particular way of operating and thus thinking – but forewarned is forearmed. If we bring our own deliberate framework to the party we’ll probably be able to avoid the power of these myths…

Christians have extra motivation to do this – we have a social network that is conforming us into a different image. We are participants in the body of believers, the church. United with Christ, by the Spirit, as God’s children. Being conformed into the image of Jesus – while avoiding competing patterns.

“Do not conform to the pattern of this world, but be transformed by the renewing of your mind. Then you will be able to test and approve what God’s will is–his good, pleasing and perfect will.” Romans 12:2

The insights from media ecology and modern neuroscience aren’t teaching us anything that Christian theology didn’t already know – we are shaped by what we think about, and by how we receive and process information. If we’re going to avoid being manipulated by the media we use, and the myths they carry, we need to think hard and deliberately about how to avoid the patterns they try to imprint on our thinking – and the changes they make to our brains. There’s nothing wrong with your brain changing – that’s natural. But being in control and having your mind “renewed” is the goal.

This post, with some practical steps, will be particularly focused on a Christian approach, but hopefully the principles will be able to be extrapolated (because they’ll also draw from media ecology and neuroscience).

As I was reading stuff for this post, and as I was writing it, I read a stunning book on approaching communication mediums as a Christian. I’ve read a bunch of these – and this is absolutely the best out there. This post took so long to write that the book got its own separate review – if you want to read a whole book, rather than an 8,000 word blog post, please check out Andy Byers’ TheoMedia: The Media of God and the Digital Age . You won’t be disappointed.

. You won’t be disappointed.

1. Bring your own ‘myth-busting’ narrative (and deliberately be multi-medium)

To recap previous posts – the reason mediums aren’t neutral tools, the reason they can subtly change how we think and act as we use them, is that communication mediums come pre-loaded with myths that shape how we use them, and this shapes our thinking, which rewires our heads.

Media aren’t just channels of information. They supply the stuff of thought, but they also shape the process of thought. – Nicholas Carr, The Shallows

“When we go online, we, too, are following scripts written by others—algorithmic instructions that few of us would be able to understand even if the hidden codes were revealed to us. When we search for information through Google or other search engines, we’re following a script. When we look at a product recommended to us by Amazon or Netflix, we’re following a script. When we choose from a list of categories to describe ourselves or our relationships on Facebook, we’re following a script. These scripts can be ingenious and extraordinarily useful, as they were in the Taylorist factories, but they also mechanize the messy processes of intellectual exploration and even social attachment. As the computer programmer Thomas Lord has argued, software can end up turning the most intimate and personal of human activities into mindless “rituals” whose steps are “encoded in the logic of web pages.” – Nicholas Carr, The Shallows

“First, like the telephone, the function of social media is to connect physically distant people. But any time people are connected through a medium, that connection happens within the rules of the medium. Our question then should not be “Is it real?” because connecting online is just as “real” as talking on the phone or sending a letter. The better question is, what are the rules of the medium and what are the underlying messages and patterns that emerge from those rules?“ – John Dyer, From the Garden To The City

Dyer has this to say about Facebook’s mythic messages and their impact on our thinking…

“Blogger and web developer Leisa Reichelt uses the term “ambient intimacy” to describe this background connection. She writes, “Ambient intimacy is about being able to keep in touch with people with a level of regularity and intimacy that you wouldn’t usually have access to, because time and space conspire to make it impossible. In order to achieve ambient intimacy, friends need to continually post things about themselves—what they are thinking, feeling, and doing—for their friends to read about. To maintain this pattern, we have to regularly think about what we’re thinking, feeling, and doing and then decide which of those things to communicate. In other words, when we do community online we have to think about ourselves much more than when we do community offline… This feedback loop of thinking about oneself is why many people conclude that the Internet makes us narcissistic… As far back as Cain’s city, we’ve said that our flesh will do whatever it can to make technology an idol of distraction. In the online world, the great danger is that we are constructing an idol of ourselves and becoming distracted with our own beauty… We are continually tempted to construct a Tower of Babel unto ourselves rather than work together on being the people of God, conformed into the image of his Son… Those born into Internet culture and those who feel comfortable in it will need to spend more time challenging it in order to avoid subtly giving in to its negative tendencies.”

These tendencies come in the embedded values, myths, or narratives surrounding and promulgating a platform, so, for example, Facebook’s is that by using Facebook you are more connected to your friends and the world.

As Christians, we already have a paradigm shaping narrative, the Gospel, a story that not only transforms our minds – but transforms our approach to media. What does this mean when it comes to Facebook? It means, firstly, that we’ll be suspicious of the narrative Facebook brings, but our use of Facebook will also be governed by priorities about our thinking, relationships and use of time that come from our understanding of who we are in Christ, where we’re heading, how we’re meant to live, and who it is that shapes our lives. Peter may as well have been writing about Facebook when he wrote these words…

Therefore, with minds that are alert and fully sober, set your hope on the grace to be brought to you when Jesus Christ is revealed at his coming. As obedient children, do not conform to the evil desires you had when you lived in ignorance. But just as he who called you is holy, so be holy in all you do; for it is written: “Be holy, because I am holy.” – 1 Peter 1:13-16

And this actually works. Having a controlling narrative robs little narratives of their power. Here’s how Andy Byers sums up some pretty similar advice in his most excellent TheoMedia, he also appreciates the opportunity social media presents for Christians to live like Jesus – to be “incarnate,” to carry our message to mediums that lower the barrier between medium and messenger (which is one of the features of profile-driven social media platforms, we naturally become part of the medium), but more on that later…

“Social media companies are providing us with a platform. It is not their job to police poor grammar or correct bad theology promulgated through their channels. As media platforms, Twitter, Tumblr, Blogger, and WordPress offer remarkable opportunities for conducting God’s mediated voice into the cybersphere. I just think it is important for us to recognize that behind the graphics on the screen are corporations with budget goals, profit plans, marketing strategies, and other business-oriented agendas. These are not necessarily corrupting influences. But they are there, barely perceptible in those imperatives (“just write”) and questions (“what’s happening, Andy?”). Responsible use of media technology means we that rely on more authoritative voices to govern our online activity than those coming from executives poised in their corporate suites. As Christians, we take our theological and technological cues from elsewhere… ”

… as media and religion specialist Heidi Campbell points out, there is the assumption in the extreme, distilled version of this more cautious perspective that media technology use will always shroud and distort human culture, so that we are left only with the ability to respond to its power or educate ourselves against its control. This approach often allows only for acceptance or rejection of technology in light of religious values. It does not leave room for considering how religious values may lead to more nuanced responses to technology or the creative innovation of aspects of technology so they are more congruent with core beliefs…

Heidi Campbell has proposed a more nuanced approach for understanding religion and media: “the religious-social shaping of technology.” She has found in her extensive observations that although communication technologies have the capacity to influence their users, religious groups often resist those influences and bring their theological traditions to bear on how they use them. In other words, although religious folks may indeed be shaped by the technologies they employ, at the same time they exert their own influences on media, incorporating communications technology within their existing conceptual grids and forcing some degree of theological compliance. As John Dyer succinctly puts it, “Technology should not dictate our values or our methods. Rather, we must use technology out of our convictions and values.” – Andy Byers, TheoMedia

I’m going to go a step further than simply suggesting that we use each technology, separately, within our existing value system, and suggest that using multiple platforms, deliberately (ie with thought and thinking about how to use them differently), dilutes the pull of particular narratives and the power of different platforms to completely shape your thinking. This deliberate mastery over multiple platforms will stop single platforms mastering you, and hijacking your head. It’ll help you notice the distinctives of different platforms, which is a shortcut to spotting a “myth”…

Choosing your narrative, and using tools and mediums according to your existing values, is the best way to control the “shaping” that is happening.

Dyer, who wrote From the Garden to the City has a useful five-pronged approach to ‘mythbusting’:

1. Valuation: “We must begin by continually returning to the Scriptures to find our Christian values and identity. From that perspective we can evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of technology and determine what values will emerge from the tendencies of use built into its design.”

2. Experimentation: “Thinking about technology is helpful, but it’s difficult to discover the tendencies and value systems built into a technology without actually using it”

3. Limitation: “Once we understand the patterns of usage of a technology, the next step is to see what happens when we put boundaries on it. If we become convinced that spending too much time on social media sites invites narcissism and that reading online limits deep thinking, then a disciplined set of limits is necessary.”

4. Togetherness: “The previous three steps—valuation, experimentation, and limitation—will be rendered mostly useless if we practice them in isolation apart from the context of Christian fellowship.”

5. Cultivation: “we must be careful not to enter into a kind of inactive stasis where we talk about technology but fail to support those who are actually doing technology in service of what God has asked of his image bearers: to cultivate and keep his creation and to make disciples of all nations. In recent years, Christian communities have been rediscovering the importance of cultivating and nurturing artists, and I think the time has come for us to begin doing the same with those working in technology. We already spend time and resources developing and encouraging business people and politicians, yet it is the technologists—the men and women creating the next generation of tools—who are often implicitly making important decisions about health care, energy, Internet regulation, privacy, weapons availability, biomedical advances, and so on.”

2. Keep your head and hands ‘active’ inside and outside of social media

Most of the people who are worried about what the internet is doing to our head – those like Nicholas Carr – are quite fond of the effect books have on the head, Christians, who are people of the book (or at least people of words, people shaped by a story, if we don’t want to get to medium bound) should also probably into books – or at the very least reading long, coherent, literature presented in a logically linear form. Here’s a little ode to the book (and its effect on the brain) from Carr’s The Shallows.

“Readers didn’t just become more efficient. They also became more attentive. To read a long book silently required an ability to concentrate intently over a long period of time, to “lose oneself” in the pages of a book, as we now say. Developing such mental discipline was not easy. The natural state of the human brain, like that of the brains of most of our relatives in the animal kingdom, is one of distractedness… Reading a book was a meditative act, but it didn’t involve a clearing of the mind. It involved a filling, or replenishing, of the mind. Readers disengaged their attention from the outward flow of passing stimuli in order to engage it more deeply with an inward flow of words, ideas, and emotions.”

“In one fascinating study, conducted Washington University’s Dynamic Cognition Laboratory and published in the journal Psychological Science in 2009, researchers used brain scans to examine what happens inside people’s heads as they read fiction. They found that “readers mentally simulate each new situation encountered in a narrative. Details about actions and sensation are captured from the text and integrated with personal knowledge from past experiences.” The brain regions that are activated often “mirror those involved when people perform, imagine, or observe similar real-world activities.” Deep reading, says the study’s lead researcher, Nicole Speer, “is by no means a passive exercise.” The reader becomes the book. The bond between book reader and book writer has always been a tightly symbiotic one, a means of intellectual and artistic cross-fertilization. – Nicholas Carr, The Shallows

This ‘incarnate’ relationship between book and reader – at least in the mind – is pretty interesting territory to explore, theologically, but for the purpose of the current exercise we’ll simply note that books seem to do desirable things to our head, and If it’s true that the “reader becomes the book” then books are arguably every bit as dangerous, if not more dangerous, than social media in terms of warping your mind… Reading books from one author, or on one topic, will skew your head and your thinking, potentially to a greater extent, than simply relying on one social media platform. The same advice “forwarned is forearmed” applies here as it does for social media – we should be aware of what is going on for our brains, and trying to exercise and stimulate them in multiple ways, not getting them addicted to a particular fix. So reading widely is probably important for a well rounded mind.

By the by, I love this advice and concept…

“Read at Whim. I learned this principle from the essayist and poet Randall Jarrell, who once met a scholar, a learned man and a critic, who commented that he read Rudyard Kipling’s novel Kim every year. Jarrell’s response: The critic said that once a year he read Kim; and he read Kim, it was plain, at whim: not to teach, not to criticize, just for love—he read it, as Kipling wrote it, just because he liked to, wanted to, couldn’t help himself. To him it wasn’t a means to a lecture or article, it was an end; he read it not for anything he could get out of it, but for itself. And isn’t this what the work of art demands of us? The work of art, Rilke said, says to us always: You must change your life. It demands of us that we too see things as ends, not as means—that we too know them and love them for their own sake. This change is beyond us, perhaps, during the active, greedy, and powerful hours of our lives; but during the contemplative and sympathetic hours of our reading, our listening, our looking, it is surely within our power, if we choose to make it so, if we choose to let one part of our nature follow its natural desires. So I say to you, for a closing sentence, Read at whim! read at whim!” – Alan Jacobs, The Pleasure of Reading in an Age of Distraction

For every person who loves a good book – there are those, like Plato (see previous post), and Schopenhauer, who were worried about what books do to free thought and one’s ability to think outside the box, or books…

“The difference between the effect produced on the mind by thinking for yourself and that produced by Facebook is incredibly great… For social media forcibly imposes on the mind thoughts that are as foreign to its mood as the signet is to the wax upon which it impresses its seal. The mind is totally subjected to an external compulsion to think this or that for which it has no inclination and is not in the mood… The result is that much web browsing robs the mind of all elasticity, as the continual pressure of a weight does a spring, and that the surest way of never having any thoughts of your own is to log on to Facebook every time you have a free moment.” (NOTE: The Facebooks, social media, and web browsing in this quote originally referring to the reading of books), – Freney, citing A Schopenhauer, Essays and Aphorisms

Be it Facebook, or books, there is something to be said, given our developing knowledge of neuroplasticity, for the concern that too much of a thing will shape your head into the image of the thing. But Carr actually thinks (and I’m with him on this bit), that reading well might spur us on to think better.

The words of the writer act as a catalyst in the mind of the reader, inspiring new insights, associations, and perceptions, sometimes even epiphanies. And the very existence of the attentive, critical reader provides the spur for the writer’s work… After Gutenberg’s invention, the bounds of language expanded rapidly as writers, competing for the eyes of ever more sophisticated and demanding readers, strived to express ideas and emotions with superior clarity, elegance, and originality. The vocabulary of the English language, once limited to just a few thousand words, expanded to upwards of a million words as books proliferated. – Nicholas Carr, The Shallows

I’d suggest – and I think Carr agrees, though he sort of beats around the bush a little – that taking various streams of data from multiple mediums and platforms – and integrating them, produces a more balanced brain and better thinking too.

Book readers have a lot of activity in regions associated with language, memory, and visual processing, but they don’t display much activity in the prefrontal regions associated with decision making and problem solving. Experienced Net users, by contrast, display extensive activity across all those brain regions when they scan and search Web pages. The good news here is that Web surfing, because it engages so many brain functions, may help keep older people’s minds sharp. Searching and browsing seem to “exercise” the brain in a way similar to solving crossword puzzles… – Nicholas Carr, The Shallows

There is an odd tendency (well, not really, it’s completely understandably given the vested interests) for writers of books to romanticise the reading of books as some sort of panacea for the changing brain. I don’t want to do that. Books, journal articles, long form essays… they’re all part of a healthy and varied diet of media. But I think the real key to having your brain is in charge isn’t so much in consuming the thoughts of others, without thought, it’s in thinking for yourself. In that sense I reckon the slightly paranoid (and reworked) Schopenhauer quote above is onto something. When we read something that someone else has written – that they have put a piece of themselves into, and when we make that connection where we put a piece of ourselves into their thoughts and let them occupy our heads, a sort of overlapping incarnation, we begin to think other people’s thoughts and have our heads shaped by their view of the world – now that’s fine if you want to think like your favourite author, but it’s a little bit scary. Just a little. And it’s enough to encourage me to make sure I read widely, but also to try to proactively think independently, and, perhaps, write my own thoughts down. Or type them. Creating your own words, deliberately, and putting them in mediums you choose, mindful of the myths involved in the platforms themselves, is probably the best way to stay in the driver’s seat when it comes to your brain that I can think of. It’s active rather than passive. And, in a post I wrote about TED a while back I discussed how I think it actually sort of works to help you integrate and process stuff. This effect is no doubt amplified if you do have an organising myth, or paradigm shaping narrative that helps you understand the world.

There’s a real circularity here where the media we consume is pretty important in terms of how we choose and identify a paradigmatic narrative that shapes our approach to life and helps us systematise and understand information, but the story also shapes that communication mediums we use and the information we encounter. This is particularly true for Christians, and I think it’s part of the reason the Bible simultaneously offers such effective advice (content) and is so effective at shaping our thinking (form/medium), by encouraging Christians to set their minds on a particular path via a regular dose of ‘TheoMedia’ the Biblical authors are deliberately shaping their readers’ thinking, and providing the thoughts.

It’s interesting how in both these passages – from Colossians and Philippians – which seem so apt to this sort of neuroscience meets media ecology exercise – link a healthy Christian mind to the concept of ‘peace’ in our hearts and minds…

Since, then, you have been raised with Christ, set your hearts on things above, where Christ is, seated at the right hand of God. Set your minds on things above, not on earthly things. For you died, and your life is now hidden with Christ in God. When Christ, who is your life, appears, then you also will appear with him in glory…

Let the peace of Christ rule in your hearts, since as members of one body you were called to peace. And be thankful. Let the message of Christ dwell among you richly as you teach and admonish one another with all wisdom through psalms, hymns, and songs from the Spirit, singing to God with gratitude in your hearts. And whatever you do, whether in word or deed, do it all in the name of the Lord Jesus, giving thanks to God the Father through him – Colossians 3:1-4, 15-17

It’s also interesting how many hot-button neuroplasticity related activities Paul nails in this passage in Philippians 4. Prayer, thankfulness, mindfulness, focused thinking, and acting out one’s beliefs, are all incredibly powerful tools for shaping the mind. It’s possible that the “do not be anxious about anything” is followed by a neuroplastically sound approach to not being anxious. That actually works…

“Do not be anxious about anything, but in every situation, by prayer and petition, with thanksgiving, present your requests to God. And the peace of God, which transcends all understanding, will guard your hearts and your minds in Christ Jesus.

Finally, brothers and sisters, whatever is true, whatever is noble, whatever is right, whatever is pure, whatever is lovely, whatever is admirable—if anything is excellent or praiseworthy—think about such things. Whatever you have learned or received or heard from me, or seen in me—put it into practice. And the God of peace will be with you.”

3. Be actively “Incarnate” on social media in order to lovingly accommodate – but don’t be a passive part of the machine

The last two points serve as something of a defence against letting Facebook take control of your head – but what if you want to take control of Facebook, using your head? I think there’s something to be said for modelling how we communicate to the world around us on how God chose to communicate and reveal himself to us, and I think there are two nice theological words that help.

Because God is infinite and completely without limit it would blow our little, tiny, finite minds to even begin to comprehend just a tiny bit of that vast gap between us without his help. There is now way we can really understand God as he really is without him revealing himself to us. We’d make up pictures of God (and people have, for as long as people have been around), but these pictures would all look kind of stupid compared to the real thing. God has to reveal himself in order to be made known – and in order to bridge the finite/infinite divide he has to accommodate himself to us. He’s the one in the position of dominance. He’s the one who needs to make the first move. And it’s like that with us – Paul says first, we only know stuff we know about God because God has revealed himself to us by the Holy Spirit, and second, people without the Spirit think we’re talking a load of rubbish…

“What we have received is not the spirit of the world, but the Spirit who is from God, so that we may understand what God has freely given us. This is what we speak, not in words taught us by human wisdom but in words taught by the Spirit, explaining spiritual realities with Spirit-taught words. The person without the Spirit does not accept the things that come from the Spirit of God but considers them foolishness, and cannot understand them because they are discerned only through the Spirit.” – 1 Cor 2:12-14

Then in 2 Corinthians 3 and 4 he talks about people who don’t know God having veils that stop them seeing God – they can’t see God without an act of accommodation. And we are the accommodaters. It is our job to try to take steps towards other people in our communication, to help them see things from our perspective by first understanding theirs. To speak the language of the people we love so that they’ll understand us, in the mediums they use.

The second part of God’s communication methodology is the incarnation – where his word, Jesus, became flesh. He didn’t become flesh and speak a crazy language that nobody around him could understand. He became flesh and spoke Aramaic, which was much more appropriate in first century Judea than it is in 21st century Australia. But that was God’s communication method from the very beginning – the Bible is a collection of literature produced in genres that were appropriate to carry particular truths about God to particular people, but also serve to communicate about God in a timeless way. The Bible is an incarnate text, produced by real people, for a God who uses incarnation as a communication methodology and expects us to do likewise…

Facebook is an opportunity for us to accommodate our message about Jesus in an incarnate way – especially if mediums change our head so that we become like the medium, this is the very essence of what incarnation is. It’s what I think Paul is thinking about when he writes:

“I have become all things to all people so that by all possible means I might save some.” – 1 Cor 9:22

This point isn’t necessarily going to protect our heads from outside influences like the first two points – in fact, it may involve you deliberately being reshaped by the medium (in this case, Facebook) in order to reach others. This becoming an “incarnate” representative of Jesus should guide our use of mediums and keep us connected to the master narrative of our lives, and to the ultimate social network – our union with Christ, and our participation in his body, the church. I wrote some stuff about using Facebook as a Christian a long time ago (in Internet years), and there’s not a lot I’d change – except that I’m much more cautious about wholeheartedly (or wholeheadedly) recommending jumping in without the caveats laid out above.

I do like this quote from TheoMedia on the way the Gospel story pushes us, as participants, to engage with the people of our generation using the communication and cognitive tools they’re engaging with…

Discerning what characterizes the socially constructed worlds people around us inhabit places us in a better position to address the generation God calls us to serve. Doing so, however, necessitates that we conceptualize and articulate Christian beliefs—the gospel—in a manner that contemporary people can understand. That is, we must express the gospel through the “language” of the culture—through the cognitive tools, concepts, images, symbols, and thought forms—by means of which people today discover meaning, construct the world they inhabit, and form personal identity. — Grenz & Franke, quoted in TheoMedia

The first sentence is a little difficult to parse – but what he’s saying is we have to think a little bit, and basically understand the myths – the stories that shape people’s lives – in order to speak to them. And this, increasingly, means doing some basic myth-busting media studies. So the exercise in the first point above isn’t completely self-indulgent and pointless after all.

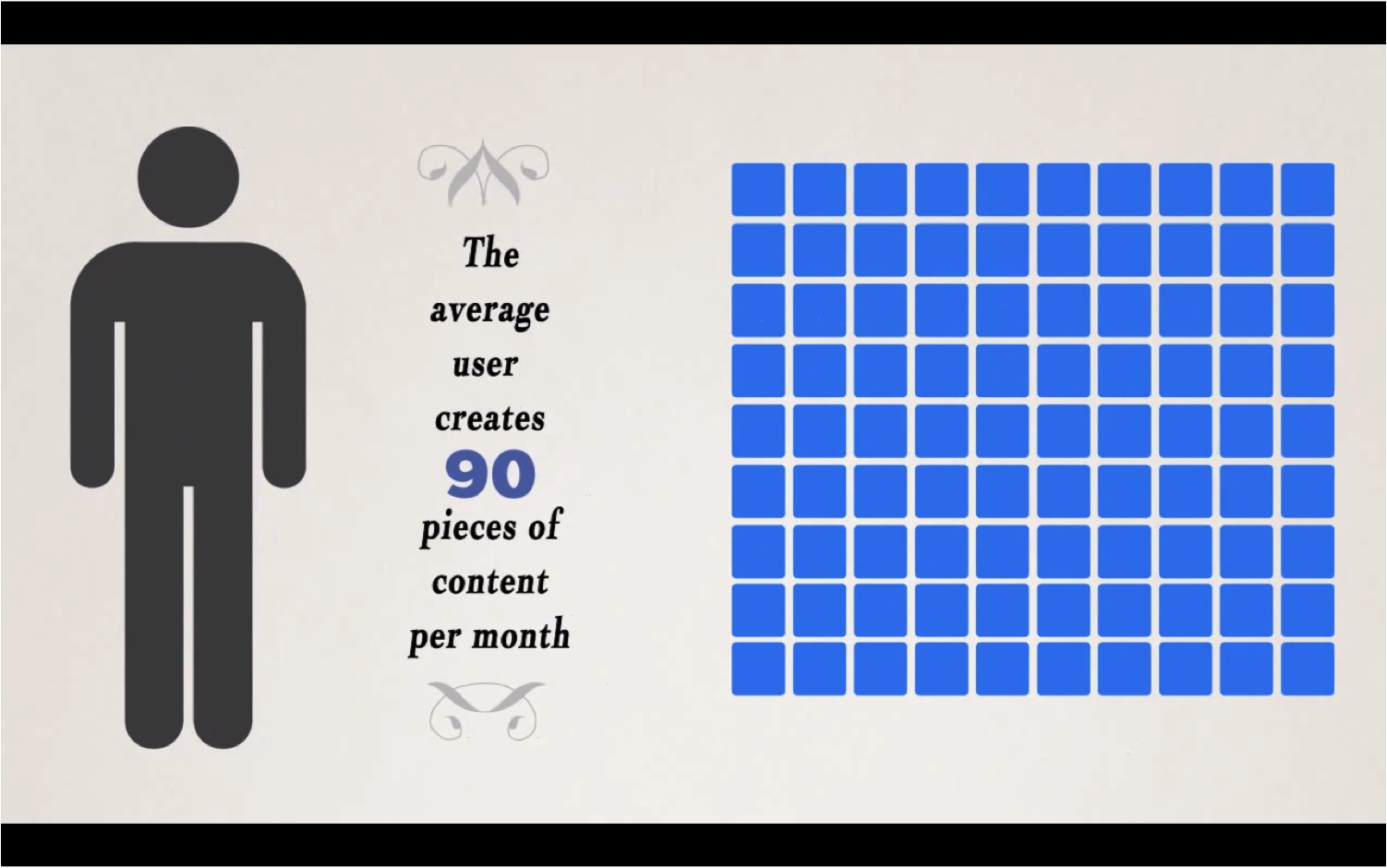

Being incarnate always comes at a cost. It always involves becoming something that you weren’t before. Sometimes the cost might be a cost you pay because you want to embrace a change whole-heartedly (or whole-headedly), other times it might be a sacrifice. Sometimes you become incarnate in something without realising – and Facebook is particularly insidious when it comes to a passive form of being incarnate, it gets its energy from your narcissism. A bit like the robots in the matrix. If you’re not paying attention, Facebook consumes your time and resources, it keeps your eyeballs fixed to a screen, by getting you addicted to the chemicals that are released when other people pay attention to you. It turns you into a more self-seeking person. If you become incarnate on Facebook without thinking, it comes at a substantial cost. To become incarnate without paying that particular cost, where you are simply viewed as a human brain and set of relationship connections to be harvested by a giant advertising corporation, you need to be aware of what Facebook is trying to do, and you need to subvert it (which we’ll get to below). It may be that subverting this is to become thoughtfully incarnate and know that you’re paying a price in your interactions by deliberately looking for ways to pay the price.

It may be that being incarnate in this medium isn’t for you – perhaps the temptation to conform to Facebook’s world of narcissism and the endless siren call encouraging you to smash your time and energy against the pointless rocks of Farmville (or whatever the kids and empty-nest mothers are playing these days) is irresistible and you’re going to wreck your life – or at least your head. At this point it’s worth keeping those words from Romans 12 bouncing around in your head like a mantra.

“Do not conform to the pattern of this world, but be transformed by the renewing of your mind. Then you will be able to test and approve what God’s will is–his good, pleasing and perfect will.” Romans 12:2

There’s a very close relationship between incarnation and idolatry – between being a person who is made in the image of the God who made them (and Jesus who remakes them), and being a person who carries the image of whatever idol they are consumed by. It’s human to reflect and promote the image of something – even if, and often, that something is you and your own glory. It’s all about the heart – and the mind. Whatever you are fixated on when you’re participating in a medium is shaping how you use it, and shaping you through your use of it.

You yourselves are our letter, written on our hearts, known and read by everyone. You show that you are a letter from Christ, the result of our ministry, written not with ink but with the Spirit of the living God, not on tablets of stone but on tablets of human hearts... And we all, who with unveiled faces contemplate the Lord’s glory, are being transformed into his image with ever-increasing glory, which comes from the Lord, who is the Spirit. – 2 Corinthians 3:2-3, 18

By the by, this is why I get so excited about the implications of the image of God for communicating in our modern multimedia world – a world where images are everywhere and trying to sell something, trying to display what it is that makes our hearts sing, is a world not too far removed from the world where Genesis landed on the scene as a text, a world full of images-as-persuasion. A world where the image you projected told everybody who you were.

If you can’t log off a medium, if you’ve become so caught up in it that you can’t walk away without believing that you are doing significant damage to yourself as a person – then it has become an idol, and you’ve become a slave. Mediums with strong myths can do that. Marshall McLuhan, the Media Ecologist, loved to quote Psalm 115 when talking about the potential for mediums to unhelpfully become extensions of our humanity…

But their idols are silver and gold,

made by human hands.

They have mouths, but cannot speak,

eyes, but cannot see.

They have ears, but cannot hear,

noses, but cannot smell.

They have hands, but cannot feel,

feet, but cannot walk,

nor can they utter a sound with their throats.

Those who make them will be like them,

and so will all who trust in them.

4. Be the “Cruciform” Medium – communicate sacrificially, and through sacrifice

The Net commands our attention with far greater insistency than our television or radio or morning newspaper ever did. Watch a kid texting his friends or a college student looking over the roll of new messages and requests on her Facebook page or a businessman scrolling through his e-mails on his BlackBerry—or consider yourself as you enter keywords into Google’s search box and begin following a trail of links. What you see is a mind consumed with a medium. When we’re online, we’re often oblivious to everything else going on around us… The interactivity of the Net amplifies this effect as well. Because we’re often using our computers in a social context, to converse with friends or colleagues, to create “profiles” of ourselves, to broadcast our thoughts through blog posts or Facebook updates, our social standing is, in one way or another, always in play, always at risk. The resulting self-consciousness—even, at times, fear—magnifies the intensity of our involvement with the medium. – Nicholas Carr, The Shallows

I think the key to subverting the power of the medium of Facebook – but this is true for every other platform I can think of – is having a narrative that shapes your life that is built around an incredible act of subversion. A narrative that is built not on building yourself up, but on dying to self out of love for others. When it comes to using the incarnation as a model for thinking about participation in a social network like Facebook, what can be a better control of how we ‘incarnate’ ourselves than the climax of God’s own incarnation in our world, in Jesus. The cross.

Most properly Christian engagement with the world is an act of subversion. Because it will be shaped by the ultimate act of subversion. Shaped by the cross (paradoxically, if these acts are consistent with the character of God, as it was revealed at the cross, it’s not subversion at all, but consistent with the approach to life humans should have had from the very beginning).

Just as Jesus subverted the most powerful propaganda medium, and the most powerful myths, of the Roman empire – by turning the crucifix from a symbol of humiliating domination into a symbol of liberating hope, rather than imperial power – we are, as we take up our crosses to follow Jesus, called to subvert the values of systems and platforms that want to glorify ourselves or our idols.

But the subversion thing probably needs some fleshing out. When it comes to the me-soaked world of social media which is about your profile. Your status. Your likes… the challenge is to make Facebook simultaneously authentically you (which is a little subversive), and not about you at all… channeling John the Baptist…

“He must become greater; I must become less.” – John The Baptist, John 3:30

This is hard on Facebook, it is hard beyond Facebook – it’s, as David Ould and I discussed recently, equally challenging for bloggers – one way I tackle this one, personally, is almost never ever checking my stats – and feeling dirty and craven when I do, I want so much for blogging to not be about me, while realising, paradoxically, that the very nature of a blog is that it is.

This means, when it comes to Facebook, for the Christian, it’s not about us. We can’t play Facebook’s me game. It’s not just about making it about Jesus so that you drive your non-Christian friends nuts – I’ve had to pull myself up on this front a little lately. We have to make Facebook about actively and sacrificially loving others, in a way that is real and unexpected – not just by hitting like on their status or telling someone they look nice in a photo. Being sacrificial and incarnate on Facebook might actually mean doing something loving in the real world. The medium you use to communicate says something about the level of sacrifice you’re willing to make in the act of communication. Part of both accommodation and incarnation involves taking costly steps to close a gap between communicator and recipient – be it on God’s part, or ours as we communicate about God. Being subversive communicators, more broadly, might mean adopting a more sacrificial medium than expected. Or approaching a medium in a more sacrificial way than intended. As a little bit of proof that mediums matter, check out this quote from one of John’s letters, and then these thoughts on it from John Dyer.

“I have much to write to you, but I do not want to use paper and ink. Instead, I hope to visit you and talk with you face to face, so that our joy may be complete.” – 2 John 1:12

“The great temptation of the digital generation is to inadvertently disagree with John and assume that online presence offers the same kind of “complete joy” as offline presence. Our problem is not that technologically mediated relationships are unreal, nor is the problem that all online communication is self-focused and narcissistic. Rather, the danger is that just like the abundance of food causes us to mistake sweet food for nourishing food, and just like the abundance of information can drown out deep thinking, the abundance of virtual connection can drown out the kind of life-giving, table-oriented life that Jesus cultivated among his disciples. Social media follows the device paradigm in that it masks the long, sometimes arduous process of friendship and makes it available at the press of a button – John Dyer, From the Garden to The City

Relying on Facebook to sustain your friendships cheapens your friendships, just as relying on Facebook for communication cheapens your communication. If you communicate using other mediums, there’s the added bonus that Facebook isn’t rewiring your brain all on its lonesome.

Being incarnate, and being properly subversive, means knowing something about the system you are infiltrating. Jesus didn’t come to first century Israel speaking English. That would’ve been stupid. And he wasn’t crucified by accident. Becoming incarnate requires some deliberate attention to detail, an understanding of the world or platform you are operating in. You’ve got to know the language of the people in order to converse – and you probably need to have some idea about how the systems and algorithms and business imperatives underlying these platforms shape what they present to the average user. So, for example, Being incarnate on social media doesn’t mean being a Super-Christian who nobody wants to hear from (like John Piper on Twitter or Mark Driscoll on Facebook) – in fact, as someone who knows a little bit of how Facebook works – that’s a shortcut to only having your posts seen by other super-Christians who already think exactly like you do. Facebook thrives on giving people exactly the information they want. And people aren’t necessarily on Facebook jonesing to be smacked in the face with a bit of Jesus. Facebook will, by the magic of its algorithm, filter your posts out for those who aren’t already into Jesus, and show your posts to the choir. Which might well be edifying… but it’s not effective.

This all sounds completely irrelevant to the task at hand – protecting your mind from the clutches of Facebook – but being subversive is a surefire way to not have your mind controlled by the system. Just watch the Matrix. Think of yourself as Neo, Morpheus, Trinity and the gang – and Facebook as the brain sucking machine driven empire and you won’t be far wrong… But those guys wouldn’t have got far, certainly not past the first movie, without knowing how the machines they were fighting against worked, or without actively fighting against them…

I really like this stuff Paul says in 2 Corinthians about his approach to sacrificial communication – the methodology we choose says something about the message we speak.

But we have this treasure in jars of clay to show that this all-surpassing power is from God and not from us. We are hard pressed on every side, but not crushed; perplexed, but not in despair; persecuted, but not abandoned; struck down, but not destroyed. We always carry around in our body the death of Jesus, so that the life of Jesus may also be revealed in our body. For we who are alive are always being given over to death for Jesus’ sake, so that his life may also be revealed in our mortal body. 2 Corinthians 4:7-11

And I like Paul’s reflections on how the incarnation of Jesus – and the cross – shape the way we treat one another in our social networks, and the way we think. This is the purple passage, I think, for approaching Facebook through the lens of the cross. How much better would relationships on Facebook be – and our heads be as a result – if this was our approach…

Therefore if you have any encouragement from being united with Christ, if any comfort from his love, if any common sharing in the Spirit, if any tenderness and compassion, then make my joy complete by being like-minded, having the same love, being one in spirit and of one mind. Do nothing out of selfish ambition or vain conceit. Rather, in humility value others above yourselves, not looking to your own interests but each of you to the interests of the others.

In your relationships with one another, have the same mindset as Christ Jesus:

Who, being in very nature God,

did not consider equality with God something to be used to his own advantage;

rather, he made himself nothing

by taking the very nature of a servant,

being made in human likeness.

And being found in appearance as a man,

he humbled himself

by becoming obedient to death—

even death on a cross! – Philippians 2:1-8

I was going to write a fifth point – about making sure you’re participating in the ultimate social network – a relationship with God, and with his people, through prayer, real world relationships in church communities, and by consuming TheoMedia – but this ultimately would just be a rehash of the first four points – it’s only as someone decides they want to participate in that social network that they become suspicious of the myths peddled by all the other social networks, it’s only by consuming TheoMedia that the narrative of the Gospel starts to not only shape our thinking (points 1 and 2), but also how we use other mediums (points 3 and 4) (note – by TheoMedia I’m referring to the concept described in the book of that name, but this includes reading the Bible, appreciating how God speaks through his world, spending time reflecting on who God is by singing, reading, mediating on the Bible, praying, reading theological books, reading blogs, following interesting Christians on Facebook or Twitter, and generally being stimulated to think about God).